Sis - Religious customs

Author: Anna Poghosyan, 18/04/15 (Last modified: 18/04/15)- Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

Khoskgab (binding word), betrothal

The custom of khoskgab could take place as early as children were still in the cradle or toddlers. Thus, it was called the “cradle oath” (orrani nshanduk in Armenian, or beşik kertmesi, in Turkish). The oath was considered valid by making a knife mark on the cradle itself. [1]

This type of betrothal occurred between families that were very close, often between those that were wealthy and displayed mutual respect. From the day of the oath, families were considered to be in-laws, and the boy and girl were seen as the future bridegroom and bride. However, as noted by Misak Keleshian, author of the book “Sis-Madyan”, this “cradle oath” custom wasn’t as widespread as other regions. [2] By the close of the 19th century this wedding tradition was gradually disappearing anyway.

The suitable age for girls to be married was fifteen and 18-20 for boys. Girls of Sis were educated to become future housewives and mothers. Prior to marriage, they mastered household chores such as doing the wash, sewing, meal preparation, milking cows and churning butter. [3] They were prohibited from leaving the house without permission, except perhaps on holidays and Sundays to attend church services. Those holiday rituals held special significance for young people. Boys and girls would wear their finest garments and attend such celebrations to be seen and to see others – a chance to meet members of the opposite sex.

All marriage related negotiations, however, were conducted by their parents. [4] A large role was played by women intermediaries who were usually expert and skilled at such matters. They would visit the home of the bride to be and negotiate with the family. The intermediary, along with the boy’s parents, would then visit the girl’s home and would familiarize themselves with the girl’s bearing, how she worked, and the level of her upbringing. They wanted to gauge if the match was a good one; if the girl would fit in with the family. The custom was to not agree immediately to the match. To get a “binding word”, the guests would have to make several visits to the girl’s family. At a minimum, they would have to make three visits, along with the local priest and other influential individuals, before the girl’s parents would consent. If the guests were served coffee without sugar, this was seen as a refusal. Sweetened coffee meant acceptance. The guests would not finish their coffee until they heard the final word of acceptance. If the matchmaking was successful, the coffee would be served by the girl. This act was called sağlam kazığa bağlamak in Turkish (Literally – strongly fastening something to a stake; i.e., to ensure success for a job or action). [5].

Nshandouk (Engagement)

The engagement would follow the “binding word” and was usually marked o a Sunday evening. The boy’s family would prepare osharag (a fruit drink) and relatives from both sides would gather. Oftentimes, the engagement would take place at the girl’s home and the drink would be sent the next day to those who didn’t participate or served to well-wishers.

Prior to the 1900s, the girl and boy were not allowed to be present at the engagement. Later on, the custom was to have the boy and girl sit in the middle of the house with their parents and relatives around them. [6] Receiving the consent of the parents, the priest would bless the token [ring] and would exchange the rings himself. By the end of the first decade of the 1900s, the boy and girl would exchange the rings themselves after having said “yes”. Once the rings were exchanged the priest would offer his blessing and the drink would be passed around as congratulations were made. The bridegroom’s parents would offer gifts to the priest, the sexton, and national institutions.

The festivities and celebratory meal, accompanied by song and dance, would start at the bridegroom’s house. The wealthy would slaughter a goat and would have sent out invitations in advance to the party. The bridegroom would present a silver or gold bracelet, as well as a gold ring, earrings, gold coins, a pair of shoes and stockings, while the bride’s parents would present a gold ring and a watch as gifts.

After the engagement, the families would make congratulatory visits. On the holidays the in-laws would invite one another for receptions and sometimes for dinner. The new bride would welcome her husband’s parents and close relatives with gifts and she was expected to kiss their hands one by one. Of particular interest is that those present, following the example of the groom’s parents, would place an amount of money in a dish. It was akin to a loan without interest that the groom would return at the weddings of the donors. The bride, starting from the engagement ritual, was not permitted to speak to her future husband and his relatives, and both boy and girl had no chance of seeing each other before the marriage, no matter how long the interim. This was considered a sign of virtue. [7]

Wedding and Nuptials

The parents of the groom send gifts (yol), in the form of sweets or other items, in cups to all the relatives. Those receiving the yol are obliged to attend the wedding and bring presents (copper pots, clothes, a ring, various foods and especially kıymalı börek, rice pudding, and sweets made from starch). [8]

Fashioning the clothes to be worn by the bride start the wedding rituals. Until the tailor is satiated with gifts, he doesn’t begin to fashion the clothes and repeats the words Makas kesmiyor (the scissor doesn’t cut) [9]. After each piece of clothing is fashioned, a round of well wishes breaks out. Close relatives visit the bride’s house and bring a pastry made from sesame oil. Inside, they place two okas (1 oka=1.28 kilograms) of kelleh sheker (a type of sweet for eating). The bride isn’t allowed to taste the pastry since tradition holds that by abstaining she will not experience any ill fortune. In order that the groom participates in this ritual, one of the women feeds him with a piece of bread that she had previously rubbed on the bride’s face. [10]

Numerous rituals, that comprised an important part of Sis weddings, preceded the nuptial ceremony itself.

One week before the wedding, people would prepare, with song and dance, the wedding bread. All the acquaintances, neighbors and friends would send chevirmeh (spit roasted soft bread) as a sign that they have participated n the ceremony. Of note is that nine chevirmeh bread were sent from the groom’s house to the bride’s house and ten from the bride’s house to that of the groom; giving an odd number. On holidays such as Christmas and Easter, the groom’s family would send a plate full of food called sini donatmış (decorating the plate) to the bride’s house. [11]

In Sis, the tradition of bringing wood at night (called düğün odun/wedding wood), was one of the rituals preceding the wedding. Five or six friends of the groom would go off to the forest to collect wood, taking along a goat or other items as food. One of the horses, colorfully decorated and laden with wood, would be taken to the groom’s house and the other to the bride’s. [12]

The festivities and games would often begin on Sunday and sometimes on Thursday, continuing until the following Sunday; i.e. the day of the nuptials. The first two nights would start with a “ring game” called yüzük in which scores of individuals would separate into two groups and would play for cash. Coffee cups were placed on a plate, and a ring was hidden beneath one. The winner would have to guess under which one. If the winning group immediately guessed the cup containing the ring, it was called deste gül (a bunch of roses which in this case signifies victory). If it took the group two guesses, the group was called darak. (In this case they would also lose ten points). Points would be lost every time a team guessed incorrectly. The game could last for hours. With the winnings, the victorious team would purchase a few goats to be roasted. [14] Those playing this game would often sing the following song:

Mdjrkian family members several years after being exiled from their native town of Sis for the last time. The photo was taken in the early 1920s, most probably in Cyprus or Syria. From left: unknown person, Hripsimeh Mdjrkian (nee Pashabezian), Yeranouhie Mdjrkian, Misak Mdjrkian, Zarouhie Mdjrkian, Haigouhie Mdjrkian, Lousadzin Pashabezian (Source: Vahé Tachjian collection, Berlin)

(Original in Armenian lettered Turkish)

Let’s go to them

Ask how they are

Find the chief of the ring game.

They are the ones confused by the ring,

Give them the right lesson.

Have you gotten angry?, tail of a dog:

Hey unbeliever, nenni, nenni.

They bring the stump from the mountain,

It comes lengthy,

The female dogs, the youth,

Hey unbeliever, nenni, nenni.

Hey the one amazed by God,

The amazed and the fallen,

The one who forgets dishes,

Hey the ones amazed by the ring.

You are young like an elder fruit

Let you head remain under the cliff,

Your mother-in-law should pluck out your eye,

Hey unbeliever, nenni, nenni.

The shepherd mounts his donkey.

Puts food in his belt,

There’s vinegar in his eyebrows.

Hey unbeliever, nenni, nenni.

A cat roams atop the roof,

(Incomprehensible)

He divines a ring in an empty cup,

Hey unbeliever, nenni, nenni.

He has a colorful garment sewn,

He has money placed in the pocket,

These things make you kiss,

Hey unbeliever, nenni, nenni.

Immediately letters are written,

The sheep comes with its lamb,

A lustful girl arises from the thicket

Hey unbeliever, nenni, nenni.

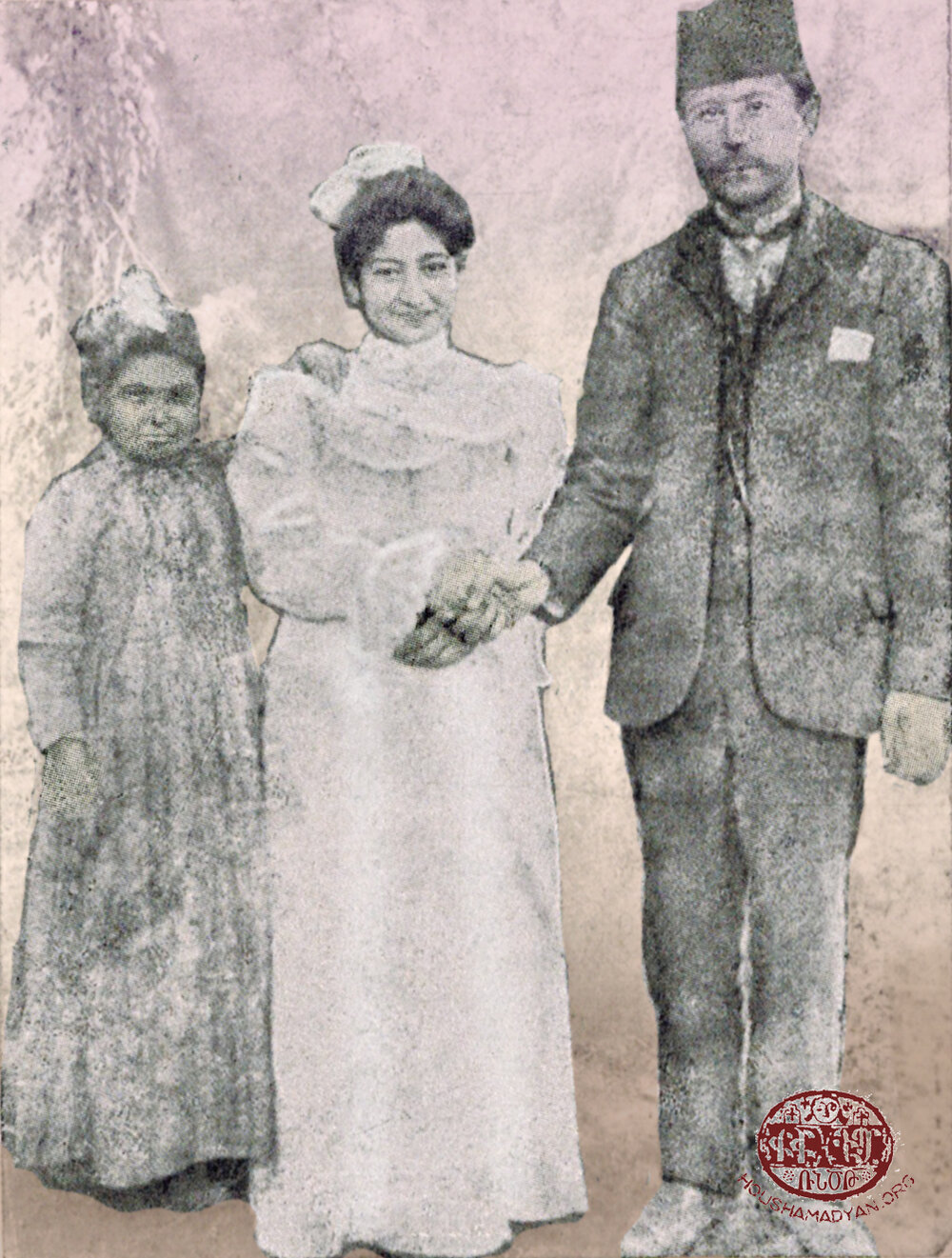

Sis - 1905 or 1906. The two adults standing in the photo are Hagop Giuliudjian and his wife Tskhiun Giuliujian (nee Kasardjian). The others are their children Tiulen, Trvon, Hatoun and Yeghsa. The two boys are Mleh Kasardjian (Tshkhiun’s brother) and Hagop Balian (a relative). The photo was taken in the Kasardjian family’s yard. (Source: Asadour Ebeyan collection, Athens, courtesy of Mike Tsilingirian)

After the “ring game”, a group laden with beverages would leave the groom’s house to visit the bride’s home to heap praises on her and to continue the festivities. At the same time, a line dance would take place either in yard of the groom’s house or up on the roof. The dancers would sing the following:

(Original in Armenian lettered Turkish)

They sow sesame behind […]

They study, they see, they chose the youth,

They save a choice orange for the friend.

This way and that are the Kurdish girls.

I graze sheep on the peak of a high mountain,

I sell the sheep, turn it into gold,

Girl, I’ll take you and make you a woman,

They are like this and that.

They sow millet on a high mountain,

They sow and reap, and make a profit,

They save the best and a pomegranate for a friend,

They are like this and that.

My shepherd sits and oils his flute,

He ties a carnation to the flute’s surface,

A youth sits and constantly weeps,

They are like this and that.

The candy eaten by the shepherd is in pieces,

The dogs are following behind,

His face like a piece of sugar,

They are like this and that.

The Kurds’ camel arrives late,

My stomach remains hungry from week to week,

The Kurds are talkative, I have trouble,

They are like this and that.

It became still behind the sadj (tray to make thin bread)

My value isn’t known,

The father’s houses have become invisible,

They are like this and that.

This song would have to be heard from the bride’s house all the way to the groom’s house so that the people assembled there would sing the following in response.

(Original in Armenian lettered Turkish)

They sat me on an Arabian horse,

They changed my direction the other way,

Send me on my way, friends,

On a seven day journey.

I descended the fortress to the plain,

I watered the narcissus,

I served for seven years

The girl with colorful eyes.

The camel is high, I can’t toss the carpet,

When you’re cold, throw a blanket over your head,

Come, let’s separate joyfully, don’t cry,

By getting irritated by someone, don’t give another hope.

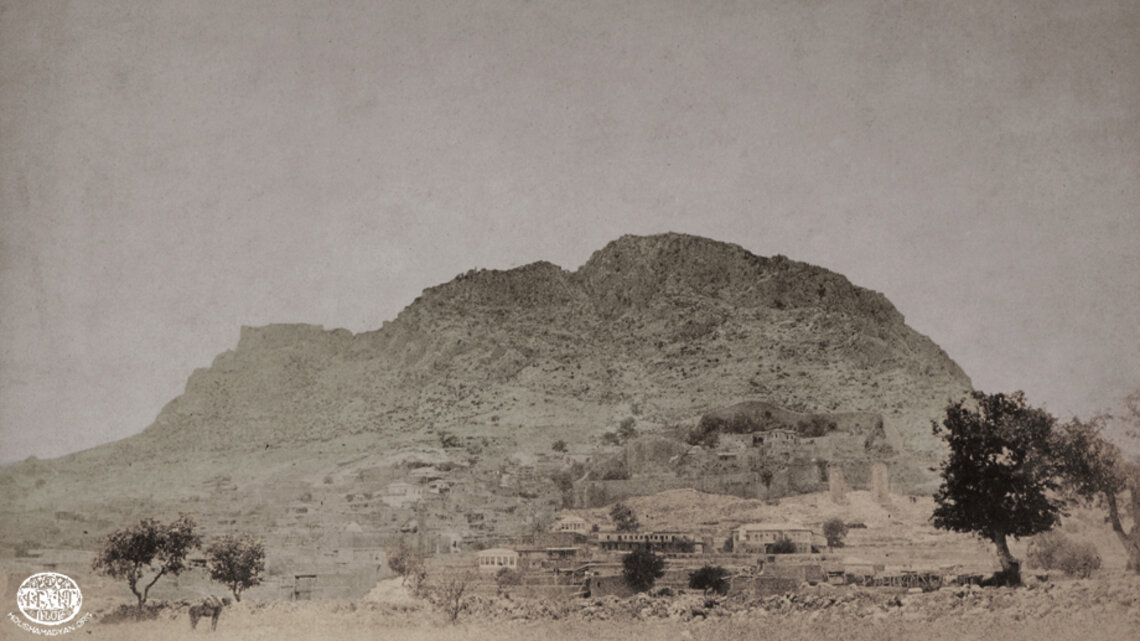

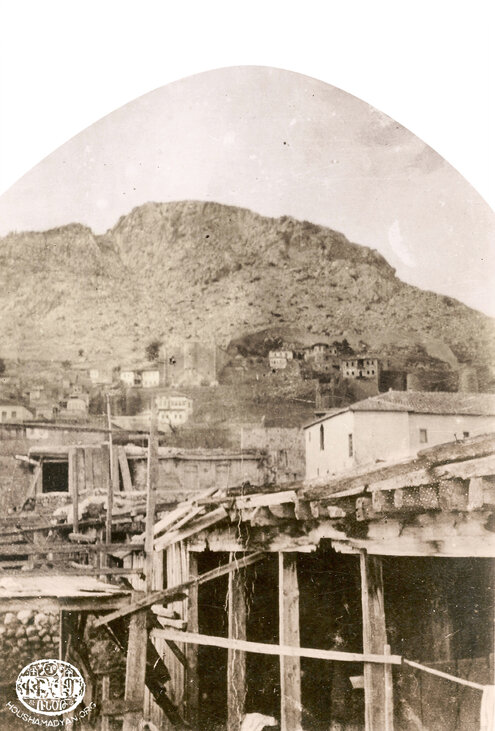

1) Sis - 1908. From left: Sahag agha Kasardjian (1840-1912), Garabed agha Pashabezian (1820-1920). The child standing between the two men is Nizag Kasardjian (a child of Sahag’s son Avedis) (Source: Vahe Yacoubian collection, Los Angeles)

2) Sis - 1904. In the front row is a portion of the house and barn of the Geokdjian family. The Armenian catholicosate appears in the center (Source: Vahe Yacoubian collection, Los Angeles)

The next day, a procession would leave for the bride’s house taking along a fat goat (kına davarı), henna and wedding attire. On display at the house was the bride’s dowry (djehiz, çeyiz) and the names of the donors of each item would be called out. Each bride had to have one trunk, a large mirror, and a large amount of clothes and linen. The dowry would be added to by close friends and neighbors. [17]

On Friday the local barber would be summoned to the groom’s house. The groom and godfather would be shaved first, followed by the other young men present. It was the accepted custom to present the barber with monetary donations that were placed in his plate. It was a wedding protocol in the form of an auction. One of the individuals present would announce the names of the donors. Instead of money, the donors could also give tens of silk handkerchiefs. These were placed on the godfather’s shoulder. As they were being groomed, those present would congratulate the godfather’s parents and say “sağdıç gördün güveyi görsün” (you saw the godfather, also see the groom). The godfathers were usually young men or boys. After getting their haircuts, only those donating the highest price had the right to make the sign of the cross with henna on the hands of the godfather and groom. [18] During the grooming, the “fake loss” of the groom takes place when the young men must look for the “lost” groom. This custom is accompanied by the singing of Khorhourt Khorin (O Mystery Deep). The wedding auction also takes place at the bride’s house and the amount collected is donated to the neighborhood churches. [19]

The groom is free to sleep this night, but the following morning an entourage is prepared and sent to the bride’s house with vodka and appetizers to gain her favors (muhabbet).

People are obliged to stay awake from Saturday night into Sunday morning, especially by playing the finger game at the boy’s house. By the time dawn breaks, a line dance starts on the roofs. The ritual dressing of the bride and groom also begins. Young men, singing O Mystery Deep, dress the groom and recite the following “Hayırlı olsun, görüp göreceğin bu olsun” (Let it be happy, let what awaits them be only his). Sometimes, they also hit the groom in jest. After being clothed the groom and godfather kiss the hands of all those present and lead by the master of ceremonies (yiğit başı) the crowd proceeds to the bride’s house. Carrying lamps and torches (mahr) made of huge spruce wood, the entourage makes its way to the house with musical accompaniment.

In the meantime, unmarried woman are dressing the bride while singing. One of oft repeated songs at this ritual was:

(Original in Armenian lettered Turkish)

He goes from roof to roof,

He goes to a girl with a pearl,

I pulled and the pearl broke,

I sat and restrung it.

Our roof is on the roof,

On top is our crop,

If God grants happiness,

Let our enemies go blind.

You walk from roof to roof,

By getting irritated by someone, don’t give another hope.

If God permits,

Let a golden cradle be rocked.

The bride’s face would be covered with a transparent colorful and delicate veil. The bride was obligated to wear the veil until giving birth for the first time. [22] A round cake with candles, given by the godmother (sağdıç anası), would be placed on the bride’s head and the following sung. [23]

(Original in Armenian lettered Turkish)

Is the hand henna made from mud?

Is that rubbed on the eye made from coal?

Is the mother’s heart made from iron?

Our girl flirts,

Our boy will become a king.

He/she has a pearl of fire, a pearl of light,

He moves his hand, it has the color of fire,

He has a sister-in-law with a huge gaze,

She flirts, etc.

The horses have be shoed, we came to watch,

Be quick, we must hasten,

Give us our missus, and we’ll go,

She flirts, etc.

Her face is covered with red pearls,

Her back is wrapped in a shawl,

Not three, not five, but has a sister-in-law,

Give us our missus, and we’ll go. [24]

The bride would answer:

Mother, was your girl too much?

Was a girl a burden for you?

You turned me over to foreign hands,

There was no brave one.

Let me leave your hands,

Let me get free of your tongue,

If I were a duck with a green head,

I would not drink from your lake.

Also:

There are yellow slippers on my feet, hey my love,

Girl, why do you wander on foreign shores, hey my love,

Yellow slippers (an incomprehensible word), hey my love,

(an incomprehensible word) I am orange, come! yar aman, yar aman, aman.

Today is the 14th of the month,

Girl, who braised your hair?

I you braid, my love braided,

Prove who braided.

Today is the 10th of the month,

My burden is barley flour,

Don’t pay attention to those married,

They’ll go home and forget. [25]

Those present would respond:

Three pieces of wheat fell from the sky, ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

Zabel also fell to us, ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

Birds flew from the sky, ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

Girl, your fate befell us, ha leyli, leyli, leyli.

Who will lead the dance? ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

The blue-eyed girl will lead, ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

A fish chops the water, ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

Our groom cowers, ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

I should have been this person who arrives, ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

I should have been your horse’s horseshoe, ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

Your back (incomprehensible word), ha leyli, leyli, leyli,

I should have been the tassle, ha leyli, leyli, leyli. [26]

As this was going on, the godparents would wait in the yard of the bride’s house, sing the songs requested by the in-laws and play requested games. Otherwise, the bride could not be taken from the house. Another custom sometimes practiced was for a rotten squash, watermelon or tin of ashes to be thrown on the head of the godfather, groom’s father or brother. No one had the right to get angry. Following these games and after the bride’s supporters were satisfied, they were allowed to enter the bride’s house. Upon entering, toasts and congratulations were exchanged. The groom, bride and godfather would kiss the hands of the parents and those in attendance. The custom was to give gifts of money to the bride. Until the 1900s, grooms would wait for their brides at the church. [27]

The custom of bringing the bride from house to house was accompanied by song and dance and shouting. As words of parting they would say “Aldık kızınızı, it yalasın yüzünüzü” (we took your girl, let the dog lick your face), and sing “Ey gaziler yol göründü” (hey veterans, there is a road), or “Djezayir/Cezayir marşı” (the march of Algeria). Later, the bride and groom would ride atop decorated horses to the church. They were usually led by young friends of the groom. They would usually not take the same path back. [28]

Along the way, all the neighbors and relatives would open their doors wide and invite the godparents inside. This ritual was called "eve almak” (taking inside from the house). They would also distribute gifts like domesticated animals (pets), clothes, shoes, and would toss sugar, wheat or money on the heads of the bride and groom. Arriving at the home of the groom, they would throw a pitcher or vase on the ground in honor of the bride. She would then throw a pomegranate against the door. If the fruit broke, it meant, according to tradition, that she would become the true master of the household. The godmother would twirl a round cake with lighted candles around bride’s head three times so that her thoughts and spirit would bond with the family oath. The following was sung on this occasion.

(Original in Armenian lettered Turkish)

Welcome, mother of the godfather,

Candles burn from your hand,

May you become a parvana [butterfly?],

Our girl flirts,

Our boy will become a king.

The length of the rivers,

I couldn’t break the ice,

Come, rich man’s girl,

I can’t withstand the flirtation,

Leylim, leylim, leylim yar,

Come to us this night.

The rivers froze over,

The hunters (Incomprehensible)

A bride was hit for me,

A bride dressed my wound,

Leylim, leylim, etc.

A star, like a ball, on the heavens,

My agha, your horse hardly stands,

Girls with breasts like oranges,

Kiss their betrothed,

Leylim, leylim, etc.

I jumped and passed the threshold,

I found the spoon on your table,

Girl, this is your fate of a mother,

A big house suits a girl,

Father, will your harvest perish?

Brother, will your bread run out?

Will a foreign girl be enough to please you?

I am satisfied, this was my destiny,

Girl, mother, this is my fortune.

He (or she) jumped and reached the (incomprehensible word),

Henna painted on his/her hand,

Without making the grandmother cry,

I too will go,

Who will I torment?

Mother, did you reach the bath?

Did you see where I bathed?

Have you understood my worth?

I too will go,

Who will I torment?

They cracked the hearth stone,

The bride covered her head,

They prepared the wedding meal,

I too will go,

Who will I torment?

A lamb was slaughtered in the yard of the groom’s house and the meat distributed to the poor. After the sacrifice was distributed and eaten, the dancing would begin. The godfather’s mother would entertain the partygoers with local dances and the groom’s parents and other relatives would join in. Usually, a pillow was placed between the groom and bride. The two would place their right foot upon it. In a display of authority, the groom would place his foot on top of the bride’s foot.

Various songs would be sung at the wedding. Most well-known is the bride and mother-in-law song:

(Original in Armenian lettered Turkish)

Mother-in-law:

The brides of this century,

Let the snakes bite their tongues,

Let them sufferer from malaria for seven years,

Let them be incapable of straightening their backs.

The window, an iron bride,

Վատ սիրտը ածուխ հարս,

Can a man withstand?

Bride, gnaw my foot.

They come with camels (incomprehensible word)

I always share the hurt of the bride,

Let the third and fourth die in a day,

Those who see the trouble in my head.

The ship turns around the quay,

It is full of the drunk and the awake,

Those drunk could use some desert,

As for the brides, a beating.

Bride:

My mother-in-law’s name is angel,

Let one of her eyes go blind,

The big one with no honor is livelier than me,

Her tongue and mouth never stop.

My mother-in-law’sblack hound,

Grows now and then,

I won’t look for what it braids,

It bites now and then.

My mother-in-law’s pot cover,

My sister-in-law is like a guard dog,

My betrothed’s ball of sugar,

My brother-in-law’s honey beehive.

Mother-in-laws are impudent,

Their hands and face are awkward,

The best is the thief,

He also looks for a bashful bride.

The mother-in-law’s snake tooth,

The sister-in-law’s head is bald,

The guys, the ring’s stone,

They don’t hurt the bride’s head.

Refrain:

Mother-in-law, mother-in-law, get up and dance like a bride,

You dance and I’ll play,

Hürük, my son, hürük.

We’ll come before it’s night,

Give the body in the morning,

Tralala, tralala.

I want to mount a horse,

I want to go down to the river’s edge,

My love with the colorful eyes,

I want to see again.

Akh, the myth of tri tri,

The twin candles are lit,

Let the clothes to be worn by my love

Be beautiful. [30]

The day following the nuptials, all the relatives would visit the groom’s house. The groom, however, wouldn’t be there because only the womenfolk would get together that day. The bride would be bathed and adorned, a ritual called “baç yaykamak” (washing of the head). They would cut a small clump of her hair with a pair of scissors; they would ask the bride whether they should cut her tongue or hair. Cutting the tongue would mean not letting the husband’s parents to talk. [31]

The godmother had the right to fashion the bride’s hair. She would do it by reciting the following: (Translated from the Turkish)

“Congratulations, in-laws. Let God make them happy, branch out, and let their two heads grow old on the pillow. Let the head of our bride be at peace, (incomprehensible word), let this be what they see. Let the enemies’ eyes go blind and those of friends get illuminated. Let God make them happy. Best of luck to your other children. Let God always watch over them”. [32]

Then, the godmother would turn to those present and say: “In-laws may your eye watch over their house, the house of the newlyweds, and the body of the children.”

The groom’s mother would respond: “Godmother, may you be in the light. Let God grant love and friendship. If they are wolves, let them become sheep. Let God make them happy, I will give but will not accept back. Let this be what they see. Let them grow old on one pillow. Best of luck to their children.”[33]

This conversation would be repeated during the dressing of the bride as well.

The next day close relatives of the groom and others would pay a visit to the bride’s family home. The family was obligated to prepare a feast that day. This custom was called “güveyi daveti” (groom’s invitation). The groom would receive gifts on that day. [34]

For the next week, the bride’s mother would send all types of meals to the groom’s house. On the fortieth day, the bride would go to church and from there to her parent’s house where she’d stay for a week. [35]

Childbirth

The important responsibility of delivering the child was given to the grandmother (ebeh), who generally wielded great influence over the other family members. When it came to making family decisions (negotiations with neighbors, engagement and marriage matters) her voice was heard. She would freely attend church and participate in various events. At funerals, the grandmother would serve as the paid mourner, singing her elegies. [36]

A bride giving birth would stay in bed for at least a week, and wouldn’t see the sun until the fortieth day. The bride wouldn’t even drink water for a few days and would only receive nourishment from the halvah made from dolaz (boiled syrup in butter; also called kaynar), sugar or roub (syrup), or from eating beoreg, made from kuimah (kıymalı börek); dishes prepared by her relatives. The new mother would be treated with great care and affection and would receive gifts from loved ones. They would bring copper items, clothes and sweets, in addition to gold coins. The coins would be affixed to the baby’s head cap to defend against the ‘evil eye’. To ward off evil spirits, the husband’s mother or the midwife would always be near the baby. Even though new mothers already knew how to wrap the babies in diapers, to bathe and rock them, the groom’s mother would often perform these duties. The custom didn’t exist whereby the baby would be cradled, played with, or even talked about in the presence of friends and relatives. There were mothers who respected the tradition of not talking in front of her elders until her fourth baby. The bride would wear her bride veil until the day of delivery and would replace it with an ordinary female veil on the fortieth day after giving birth. Prior to the 1900s, the tradition was for the bride to wear a fez to which was attached a veil festooned with gold adornments. The veil would fall from the forehead to below the chin and the two edges would meet like a semi-circle. In this fashion, the face would remain open. [37]

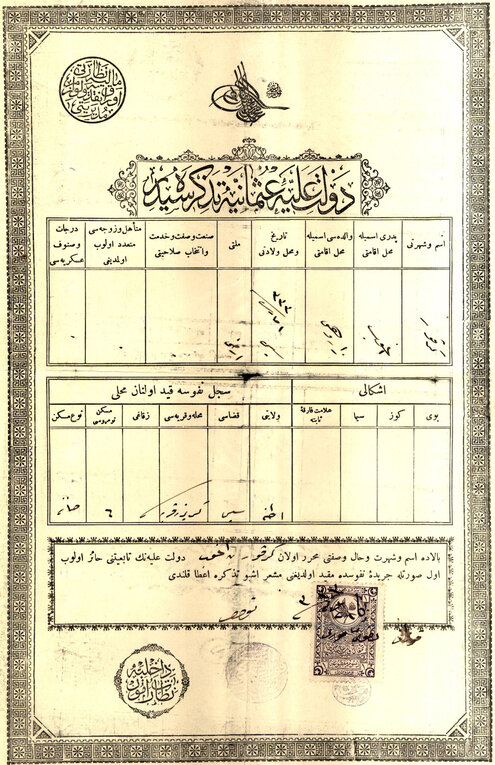

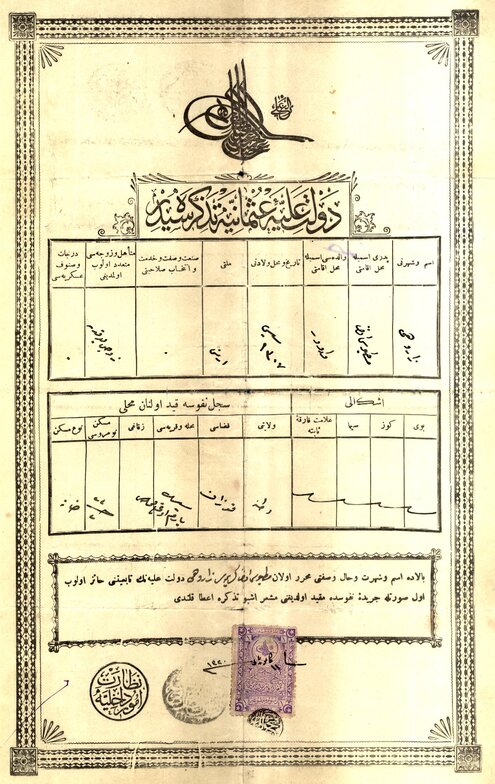

1) Ottoman identity document (nüfus tezkeresi). Belonged to Krikor; father’s name Hagop, mother’s name Zarouhie. Born Sis 1333 (Rumi calendar, corresponding to 1917). Document stamped on June 16, 1917 (Source: Asadour Ebeyan collection, Athens, courtesy of Mike Tsilingirian)

2) Ottoman identity document (nüfus tezkeresi). Belonged to Zarouhie; father’s name Mardiros, mother’s name Vartour or Vardour. Born Sis 1307 (Rumi calendar, corresponding to 1891). Document stamped on January 24, 1905 (Source: Asadour Ebeyan collection, Athens, courtesy of Mike Tsilingirian)

Baptism

Baptisms usually took place seven days after the birth of a child. The selection of the godfather was usually an inherited right, being handed down from generation to generation. The godfather or cross-bearer (saghdudj/sağdıç) wielded great authority in the community and in the family. The godfather enjoyed the same rights as parents. Prior to the baptism, the godfather was obligated to take communion and confess his sins. The godfather covered all the costs of the baptism. In return, the child’s parents would present him with gifts of a gold ring and other valuable items. [38]

Baptisms, as a rule, usually took place on Sunday or a holiday at church. The midwife or groom’s mother would take the baby to church and would bring along some soap and hot water. The parish priest would perform the baptism and hand the child to the mother while singing the hymn “Born in New Zion”. As a sign of respect, the mother would kiss the hand of the godfather. A festive meal would follow the service. In addition to the madagh (sacrifice), the guests would be served bulghur pilav, with potatoes or sheosh beoreg (şöş börek), various cakes and pastries. The godfather would be served special dishes; for example minced meat omelet. [39]

Death and Burial

Armenian cemeteries in Sis were located around the old chapel ruins or in churchyards. During the reign of the Adjapahian Catholicoi, religious and secular family members would be buried in the yard of the old monastery located in the south of town. This cemetery was considered private property and non-family members weren’t allowed to be buried there. The Turkish cemetery was located in a place where Queen Zabel allegedly had built a hospital. [40]

Prior to 1874, the government had prohibited ceremonial funeral processions. That year (the period of Chadurdju oghlu Ahmed agha), Geoydjochoukyan (Kouyumdjian) Krikor agha was able to obtain special permission by which he obtained a piece of land called Kharab Baghcheh in the eastern part of town. His relatives were able to be buried here. That spot became the community cemetery for Sis Armenians. The cemeteries belonging to the Protestant and Catholic churches were located close to the Armenian Apostolic cemetery. The cemeteries were simple plots of land encircled by stone walls. Two huge stones were placed atop the deceased’s head and feet. On rare occasions one would see a burial vault resembling a chapel like that of the family plot of the brothers Haroutiun and Hadju Hovhannes Giuzelian. [41]

When someone died all the relatives and neighbors would gather at the home of the deceased and, according to custom, would remain awake, watching vigil over the body. The tradition of washing the body was widely practiced until the 1890s. The deceased would then be wrapped in a shroud consisting of seven white sheets. The patriarchal casket, with the shape of a common stretcher, was used for the burials of rich and poor alike. After 1903 special caskets or trunk like stretchers were used to bury the dead. The house rituals were followed by a church service and then the burial procession. Usually, young men carried the caskets or stretchers on their shoulders to the cemetery. The wealthy and clergy were buried next to the church. After the burial, everyone would go to the house of the deceased for a requiem meal during which words of condolence and comfort were expressed to ease the anguish of the deceased’s family. Those present would take their leave by wishing one another the following: “Başınız sağ olsun, Allah onun ömrünü kalanlara versin... S. Hoki ile teselli bulun” (Let your head be alive, May God grant his life to the rest. Be comforted by the Holy Spirit). [42]

On the day of the burial and for one week or fifteen days hence, people would bring food to the home of the deceased. People would visit especially at night so that the family wouldn’t be alone. The parish priest would also visit the deceased’s home to comfort the family. Early in the morning on the day after the burial, close relatives or neighboring women would distribute food to the poor. The deceased’s mother and wife would not leave the house for forty days. The men wouldn’t leave for several days. There was no tradition of wearing special clothes or a black ribbon during the mourning period. However, as a sign of respect, men might not shave for a month or two. [43]

The following elegy was written by Giulliu Chosgounian, a famous Sis Armenian, and dedicated to his child who died prematurely:

(Original in Armenian lettered Turkish)

Kharab baghcha big cemetery,

Care arises, sand arises,

The big aghas of Sis,

Roam around with my spouse,

My son’s green coffin,

(Incomprehensible)

(Incomprehensible)

Saying “Mother don’t cry”

I won’t take the field road,

I won’t wear a bracelet on my wrist,

I was open to the past,

Give me a tambourine.

I’ll wear a vest on my back,

I have no more strength, spirit,

A mother needs a son,

That one saw destiny a lot.

Lemons ripen in our garden,

It has clusters of branches,

White rose, yellow lemon,

My boy was like him.

I picked poppies from the mountains,

I didn’t put them on my head with happiness,

My boy, even with my girl,

I couldn’t reach a goal.

The tent’s iron, with a rope,

A felt blanket inside,

The woman with daughter, the man with son,

We were a house, my child.

The cemetery, I reached the cemetery,

The cemetery’s grass suffocates,

I made my child a groom,

According to God’s will.

The cemetery, I reached the cemetery,

The tree blossomed,

When they all told my son,

My heart dissipated.

The barriers of the snowy mountains,

A type of blue lace

Call, let the neighbors come,

Who is my son a peer of?

The rose bush ring on ring,

Dropped its flowers today.

Don’t feel ashamed friends,

It’s the end of the separation today.

The white horse comes breaking into pieces,

(incomprehensible word) the horse comes dancing,

Now, comes my child,

Dragging the beads.

I picked cherries from the mountain,

I lost my head a bit,

Don’t feel ashamed neighbors,

Burying a boy is good luck,

Black moustaches curly, curly,

Gabriel, don’t stand opposite me,

Black paint to the colorful eye,

Do the rubbing hands grow tired?

The moustaches shouldn’t appear without laughing,

The coat should not show the fabric,

Why did you hasten so?

Without seeing your loves.

The reapers gather the crop,

They drink water from every spring,

Those with wings fly,

Fate, you broke my wings,

I equated you eyebrow to a pulled bow,

I equated you picture to the heaven’s light,

This was fate, my dear,

My child wasn’t able to love to the fullest.

The white horses are bold,

Arabian horses walk fast,

In this way a mother of a daredevil`

Doesn’t die but becomes ill-fated.

[1] Misak Keleshian, Sis-Madyan [in Armenian], Hay Djemaran Publishers, Beirut, 1949, pp. 495, 502.

[2] Ibid, p. 495.

[3] Ibid, p. 498.

[4] Ibid, pp. 495, 496.

[5] Ibid, p. 502.

[6] Ibid, p. 496.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, p. 504.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid, pp. 504, 505.

[12] Ibid, p. 505.

[13] Ibid, p. 505.

[14] Ibid, p. 507.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid, pp. 497, 506.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid, p. 507.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid, p. 497.

[23] Ibid, p. 507.

[24] Ibid, p. 508.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid, p. 509.

[29] Ibid, p. 510.

[30] Ibid, pp. 511-513.

[31] Ibid, pp. 498, 512.

[32] Ibid, p. 512.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid, p. 511.

[35] Ibid, p. 498.

[36] Ibid, pp. 498, 500.

[37] Ibid, pp. 497, 498.

[38] Ibid, pp. 498, 530.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid, p. 527.

[41] Ibid, pp. 527-528.

[42] Ibid, p. 528.

[43] Ibid, pp. 528,529.

[44] Ibid, pp. 529-530.