Bitlis (Paghesh) – Monasteries and Churches (Part II)

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 01/09/2023 (Last modified: 01/09/2023) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Monasteries of the Paghesh Diocese

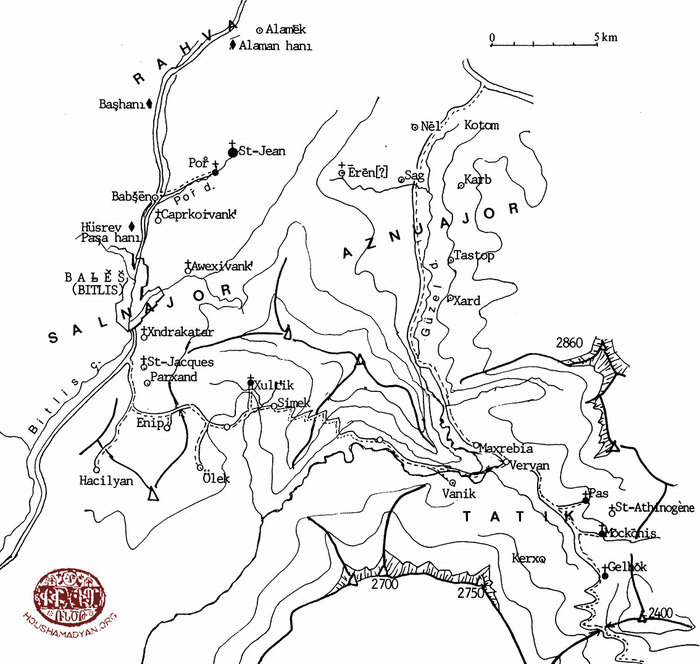

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, there were four standing monasteries on the outskirts of the city of Bitlis: the Khntragadar Holy Mother-of-God, the Amrdolou (Amlorto) Saint Hovhannes, the Komats Holy Mother-of-God, and the Avekhou Holy Mother-of-God (Saint Tateos (Thaddeus) the Apostle).

There were an additional three standing monasteries across the subdistrict of Paghesh (outside the city), namely the Saint Atanakin Monastery of Dadig (Modjgonis Monastery), the Saint Hovhannes (Saint Nareg) Monastery of Bor, and the Saint Garabed Monastery of Dzabrgor. [1]

There were two standing monasteries in the subdistrict of Khlat: the Saint Hovhannes Monastery of Teghoud and the Holy Mother-of-God Monastery of Madnavank.

In addition to these standing monasteries, sources name more than ten abandoned and derelict monasteries across the Paghesh Diocese. Among these, perhaps the most well-known was the Saint Yezdipouzd (Saint Yizdipouzid) Monastery, located near the village of Toukh.

The monasteries of Paghesh notably flourished between the 15th and 17th centuries, with a few of them becoming celebrated centers of learning and scholarship, housing schools and producing copies of countless manuscripts. [2]

In the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, the region’s monasteries were already being described as having “a glorious past, once the home of scribe-priests and thriving religious orders.” It was also stated that “at the present time,” these glories had faded into memories, and that the monasteries had simply become important museums where a large number of manuscripts were kept. [3]

One contemporary, describing the unenviable state of the Amrdolou (Amlorto) Saint Hovhannes Monastery, wrote derisively that this once-revered holy site, which had been the seat of the bishopric, was “now home only to a crone who has eaten enough corn to drive herself senile and a peasant servant.” [4] Another contemporary observed with chagrin that the monasteries of Paghesh had each become “a chiftlik [private estate or farm (Turkish) – R. T.] in the hands of local [Armenian] notables.” [5]

The functioning monasteries of Paghesh were administered by boards of trustees, which would appoint each monastery’s abbot. When there was a lack of appropriate candidates, a lay warden would be appointed to manage each institution’s budgets, oversee repairs, etc. [6]

Between 1898 and 1900, an attempt was made to bring together the four monasteries on the outskirts of the city of Paghesh under a single leadership, which would allow for more efficient administration of their estates and properties. With this goal in mind, the position of a joint co-abbot was created, to which Father Yezras Sachlian was appointed. Unfortunately, these reforms did not materialize, due to the resistance of prominent individuals sitting on the monasteries’ boards of trustees, and who had turned the monastery estates into their own private lands. [7]

The monasteries of Paghesh were frequently the targets of Kurdish raids. They were also pillaged and destroyed during the Hamidian massacres. [8]

Below are descriptions of the principal monasteries of the Paghesh Diocese.

Standing (Functioning) Monasteries

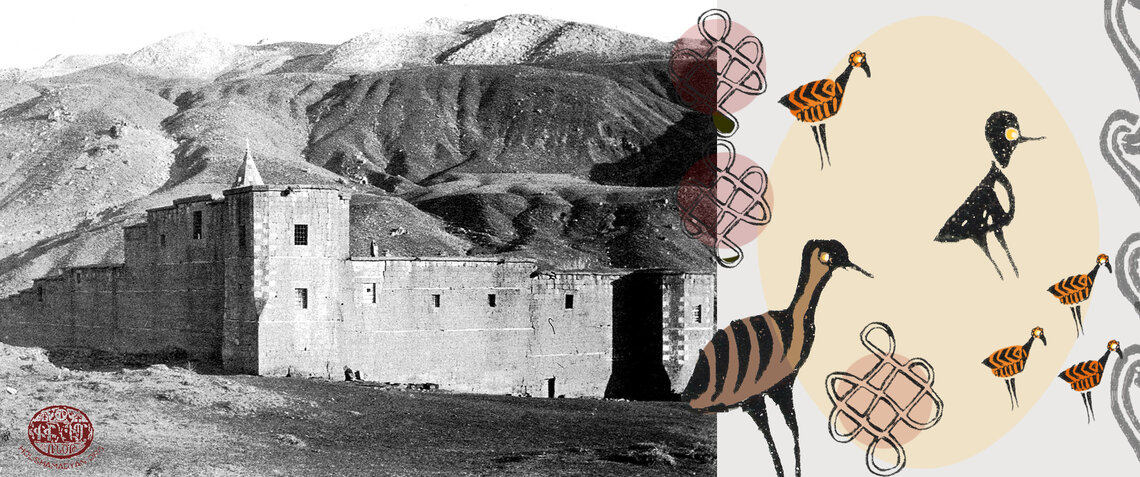

The Khntragadar Holy Mother-of-God Monastery

The monastery was located two kilometers southwest of the city of Paghesh, in a canyon near the Armenian-populated village of Amb, surrounded by beautiful and vibrant wilderness. [9] According to tradition, the monastery had been founded by the apostle Thaddeus. It was said that as he traveled across the area and founded monasteries, he arrived in Paghesh, at the site of the Khntragadar. Wishing to build a monastery at the site, he exclaimed: “I hope to die after building 1,001 churches on Earth.” After he spoke these words, a large cloud appeared in the sky, and a voice came from it: “Khntirkt Untounvetsav” [“Your wish has been granted”]. These events led to the nearby village being called Amb (“cloud”), and the monastery being called Khntragadar [“Wish-Granter”]. [10]

In the second half of the 19th century, the Khntragadar Monastery was considered the preeminent monastery of Paghesh. Its main church, which was renovated in 1870, [11] was described as a small, but “dazzling, magnificent, and beautiful,” with its steeple described as “unrivalled.” [12] The premises also included more than 30 stone, two-story buildings that served as living quarters for the members of the order and visiting pilgrims. [13]

In July 1881, a boarding school was opened in the monastery, with an initial enrollment of 12 orphans and peasant boys from indigent families. [14] An orphanage also operated in the monastery after the 1895 Hamidian massacres. [15] During the extensive renovations to the monastic complex between 1880 and 1887, a separate two-story building was built, intended as a future boarding school. [16]

The monastery’s jurisdiction included five Armenian-populated villages. [17]

In 1878, the monastery owned more than 40 plots of arable land, 90 sheep, 45 lambs, 10 oxen, seven cows, six donkeys, etc. The monastery’s premises included a hayloft, a stable, a central administrative building, and additional administrative buildings. Moreover, the monastery owned 20 stores/stalls and four homes in the city of Bitlis, which generated income. The monastery was led by an abbot (Father Yeghishe Mesrovpian), but it did not have a dedicated order (by the late 1890s, the abbot was replaced by a priest [18]). A total of 15-18 fieldworkers cultivated the monastery’s lands. Its yearly income was 15,000 tahegan (Ottoman silver kouroush), which helped fund the city’s Armenian schools. [19]

This monastery was a beloved pilgrimage site. Its pilgrimage day was on the Feast of the Ascension of Christ. [20]

The Amrdolou (Amlorto) Saint Hovhannes Monastery

This monastery was also known by the names of Amrtoli, Amlortvo, and Amirtolou. This appellation has been linked to a priest called Amrdolou (Amirtol) or Amirtovlat, who, according to legend, had either founded or had rebuilt the monastery. [21]

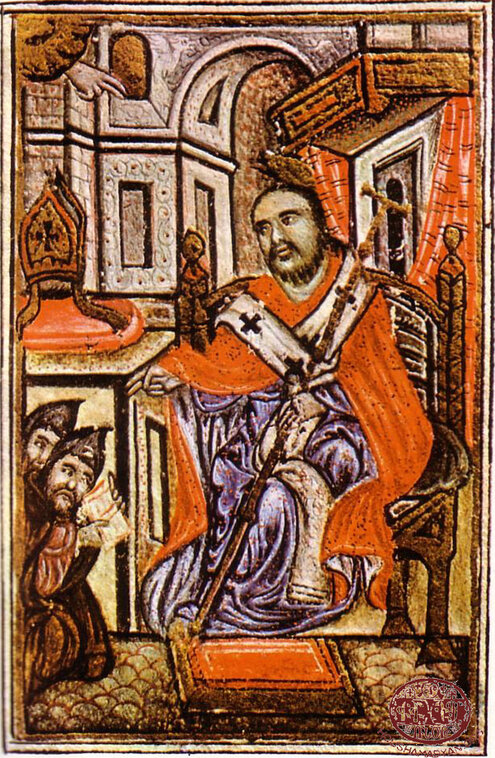

The monastery was located one to two kilometers south of the city of Paghesh, in a scenic area. [22] It is first mentioned in records from the first half of the 15th century. [23] The monastery thrived in the 16th-17th centuries, when it was one of Armenia’s principal spiritual-cultural and educational centers. At this time, the monastery housed a school, which, in addition of theology, taught philosophy, rhetoric, grammar, manuscript illumination, relief painting, etc.

Under the leadership of Abbot Father Vartan Paghishetsi (died in 1704), the monastery was home to “45 residents, of whom 40 were monks and five were caretakers and fieldhands.” This celebrated abbot added the subject of classical historical literature, in which he had a particular interest, to those already being taught at the monastery school. On his travels across the monasteries of the land, he had sought out and acquired ancient manuscripts that contained historical records, which he then arranged to have restored or copied. Thanks to his efforts, many of these manuscripts were rescued and survived into the modern age, including Ghazar Parbetsi’s Hayots Badmoutyun [History of Armenians]. [24]

Among the notable graduates of the school of the Amrdolou Monastery were Hovhannes Golod, a native of Paghesh and Patriarch of Constantinople from 1715 to 1749; and Krikor Shghtayagir, Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem. [25]

After the death of Vartan Paghishetsi, the monastery lost its cultural and educational prominence. However, it remained the seat of the diocesan prelacy. [26]

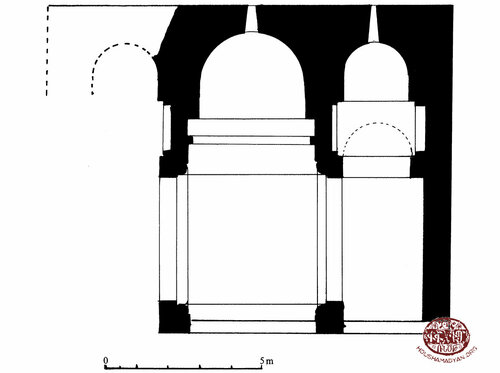

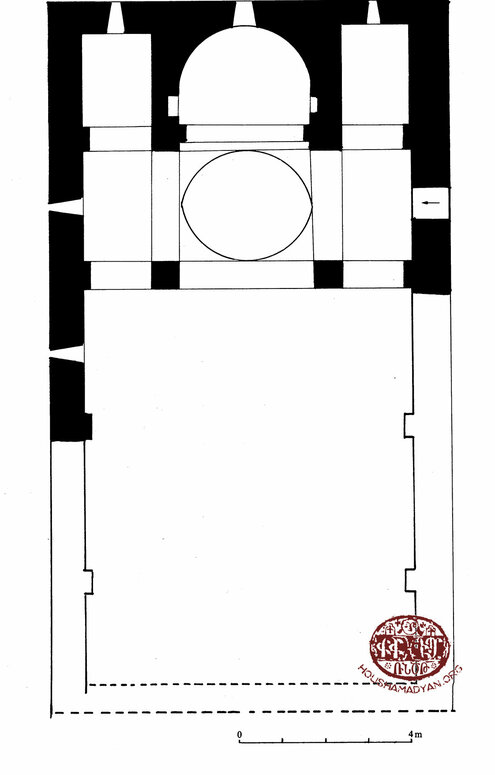

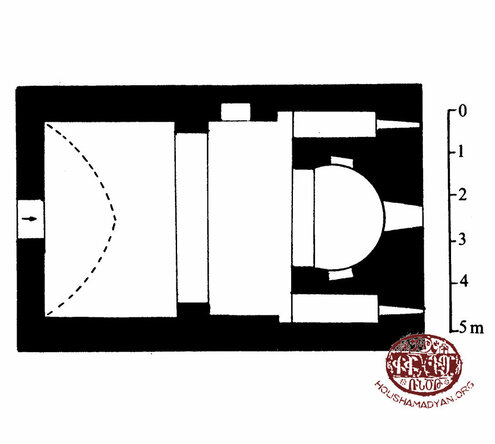

The monastery’s main church was spacious, arched, and steepled. The interior measured 10.5 x 14 meters, with two rows of arches resting on three columns each. Above the arches rose the belfry. The church was known for the various patterns and crosses carved on the stones of the walls, as well as the exquisite craftmanship of the pastoral staff and the cathedra. [27]

On the right of the sanctuary was a rock engraved with a large cross. According to tradition, this rock had been blessed by the apostle Thaddeus. Inside the church were the graves of Father Parsegh Aghpagetsou and Father Vartan Paghishetsi, prelates of Amrdolou in the 17th-18th centuries. [28]

The monastic complex included living quarters for the prelate and the monks of the order.

In the second half of the 1870s, the monastery had an income of 2,000 tahegan (silver kouroush) per year, thanks to four booths/stores and one water mill that it owned in the city. [29] In the second half of the 1890s, the monastery owned 25 stores. [30] The monastery’s jurisdiction included eight to ten Armenian villages. [31]

Probably by the 1880s, Saint Hovhannes ceased functioning as a monastery and began operating as a parish church under the management of a board of trustees. [32]

The monastery had a repository, which housed numerous manuscripts. [33] By the late 1890s, the repository was already in need of repairs. [34]

An earthquake that struck Paghesh on March 16, 1907, caused significant damage to the monastery. In a letter addressed to Catholicos Mgrdich I Khrimian and dated May 22, 1907, the serving prelate of the Paghesh Diocese, Father Parsegh Sarksian, wrote: “It is entirely destroyed. All its structures are in a state of disrepair. Seeing the heart-rending condition of this once-glorious holy site, it is impossible not to weep, not to sob. If urgent aid is not provided to repair the monastery, and another winter passes, it will irretrievably become a pile of ruins, where only the mournful wailing of the owls will be heard.” [35]

The Komots Holy Mother-of-God Monastery

It was also known as the Komats Holy Mother-of-God Monastery, and was occasionally called Dadrapnag or Dadrga Vank, due to the large population of doves that lived nearby [dadrag is Armenian for “dove”]. [36] The monastery was located to the northwest of the city of Paghesh, in a valley surrounded by mountains, on the edge of a beautiful canyon. The area was rich in water and featured a dense grove of trees. [37]

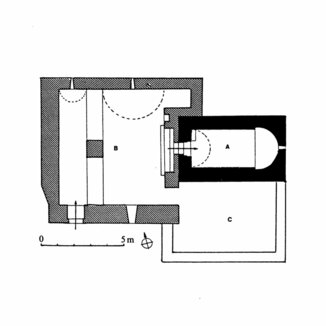

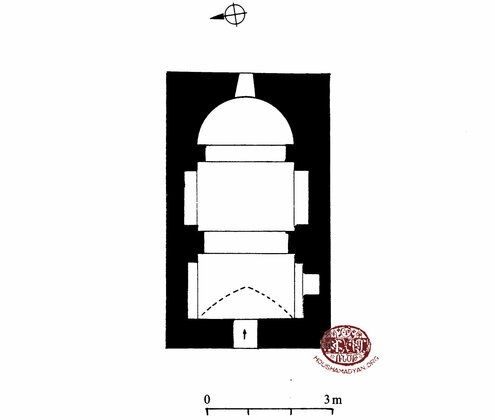

The monastery is first mentioned in records from the 15th century. [38] Like other monasteries in Paghesh, the Komots Holy Mother-of-God thrived in the 16th-17th centuries, when it housed a repository and when its monks were engaged in copying numerous manuscripts. [39] The monastery’s church was described as “small,” but also “gorgeous,” “domed,” and “beautiful.” [40] According to an inscription engraved on the main door, the church was completely renovated in 1681, during the term of abbot Father Mesrob, who also served as the prelate of Paghesh (“Land of Aghtsnyants”). [41]

In 1878, the monastery owned 20 tracts of arable land and one store, which generated an annual income of 8,000 tahegan (silver kouroush); as well as nine oxen, four cows, three donkeys, four heifers, two cattle, and 20 sheep, which produced an annual income of 10,000-15,000 kouroush. The monastery employed ten fieldhands who oversaw its day-to-day economy. The monastery’s jurisdiction included eight to ten Armenian-populated villages. [42]

In the late 1870s, the monastery’s abbot was Father Vartan. [43] Father Simeon, a priest, is mentioned as having served in the monastery in 1893. His son was imprisoned for five months for possessing and disseminating forbidden Armenian literature. [44]

In the second half of the 1890s, the monastery housed a boarding school/orphanage, financed by Gharibdjan Agha Shoghigian, a wealthy man from Paghesh. He had also funded the repairs to the church, the construction of several new buildings on the premises, and the renovation of old buildings. [45] Accordingly, in the late 1890s, the monastery was described as “newly built, small, and beautiful.” [46]

The Avekhou Holy Mother-of-God (Saint Thaddeus the Apostle) Monastery

It was also known as The Saint Tatte Monastery Avekhi, the Avekhou Monastery, and the Aver Holy Mother-of-God. It was located two to three kilometers southeast of the city.

The monastery is mentioned in records from the 15th century. [47] It especially thrived between the late 17th century and the early 18th century, under the leadership of abbot Vartan Paghishetsi and his pupil, Nerses Paghishetsi. [48]

In the late 19th century, the monastery’s main church was described as “shabby, unimpressive, and derelict,” but also as “beautiful” and “architectural.” [49] The living quarters of the resident monks were also in ruins. The monastic complex included a “small, lovely, but dirty and unadorned” chapel “built of stone.” Near it was another madourig (small chapel), in which the Christian Assyrians of Paghesh held services with the permission of the prelacy. [50]

In 1878, the monastery owned 60 tracts of arable land, four donkeys, 20 sheep, three oxen, and two cows, which generated a yearly income of 8,000 tahegans (kouroush). The number of fieldhands employed by the monastery was eight. The serving abbot was Father Shoushdag Boghos. [51]

By the second half of the 1890s, sources don’t mention any clerical presence at the monastery. The management of the monastery’s estates was entrusted to a lay villager and a few fieldhands and custodians. [52]

The monastery’s ecclesiastic jurisdiction included 14 villages. [53]

Near the monastery were twin springs, named Tateos and Tovmas after the apostles Thaddeus and Thomas (according to another source, the springs were named after the apostles Thaddeus and Bartholomew (Partoghomeos)). The springs were known for their healing properties and were a popular pilgrimage destination for devout women. [54] According to tradition, in ancient times, a girl had been cured of leprosy by rubbing mud prepared from the earth of the springs and the surrounding area all over her body. This had given the monastery its name of Avekh (a portmanteau of the Kurdish words av (water) and axa (soil)). [55]

The Saint Atanakine Monastery of Dadig

It was also known as Modjgants Monastery and the Monastery of Atanakine. It was located 35 kilometers southeast of the city of Bitlis, near and to the north of the village of Modjgonk (Modjgonis) of the Dadig village cluster, overlooking a cliff. [56]

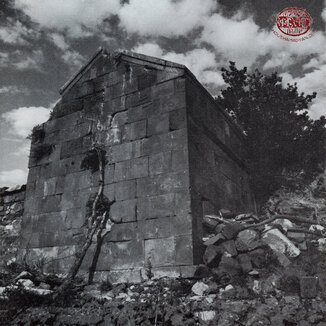

In the second half of the 19th century, the monastery was still standing, but abandoned. One visitor observed: “The church is about the size of a chapel, and the monastery lacks an abbot and living quarters. It does not have a parish.” [57]

In the 1890s, the monastery is mentioned as standing, but abandoned and deserted. The church and some of the living quarters were in a state of disrepair. Several handwritten manuscripts were kept in the monastery, but were “in a very pitiable state.” [58]

The monastery owned arable fields, pastures, vast meadows, forests, and water mills, all of which were used by the residents of Madjgonk. [59]

The Saint Hovhannes Monastery of Bor

It was also called the Saint Nareg and Naregatsvo Monastery, as according to tradition, Krikor Naregatsi (Gregory of Narek) had lived there for some time. [60] It was located six to seven kilometers southeast of the city of Paghesh, near the village of Bor. The church was steepled and described as “karagop” (built of hard, polished stone), “small,” and “beautiful.” [61]

In the 1870s, the monastery lacked an abbot and an order. It was under the care of Father Haroutyun, the priest of Bor, who had free use of the monastery’s fields in exchange for providing his pastoral services to the nearby settlements. The monastery owned 59 sheep, 12 oxen and cows, the same number of lambs and calves, etc. [62]

The Saint Garabed Monastery of Dzabrgor

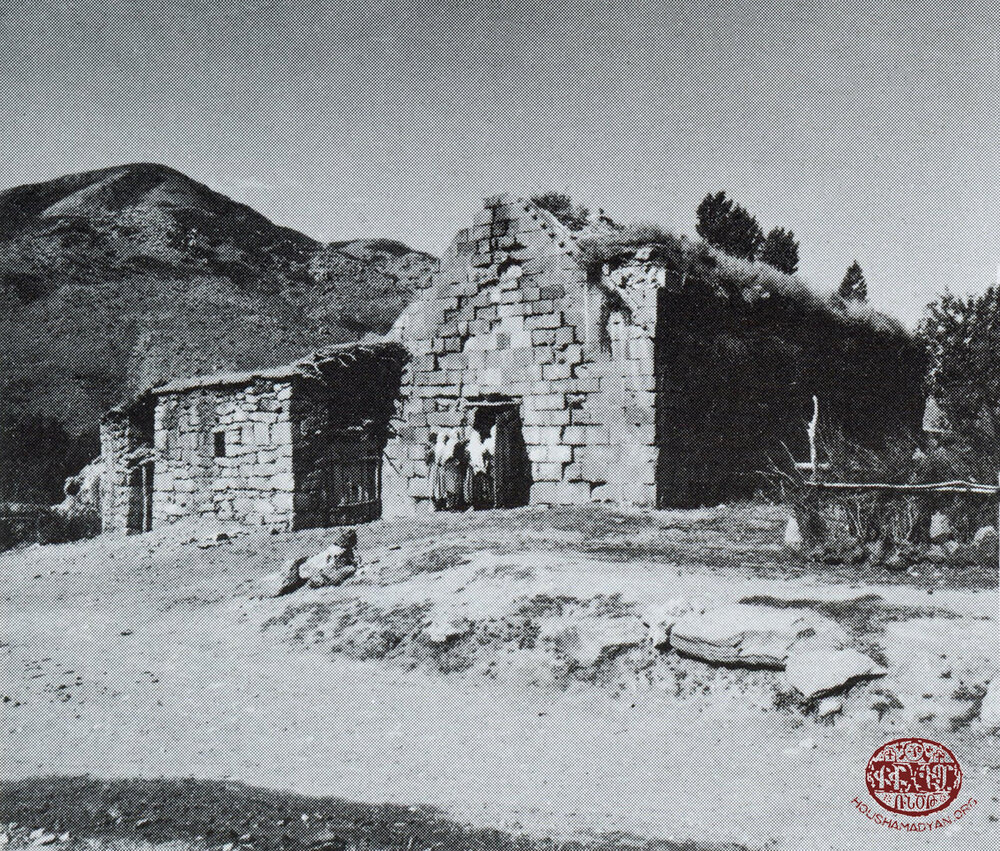

The monastery was located in the Dzabrgor or Mabrgor neighborhood, about three kilometers northeast of the city of Paghesh. It had fallen into disrepair by the late 1870s. One contemporary observed that “only the church, which was built in a very old style, and the narthex attached to it, remain standing.” [63]

According to Drtad Balian, “The monastery’s small chapel stands to this day [the late 1890s – R. T.] and serves as a pilgrimage site that always attracts the faithful. Every Sunday, the local sexton rushes to the site to burn incense.” [64]

The estates of the monastery were seized by the city’s mufti (Muslim cleric). [65]

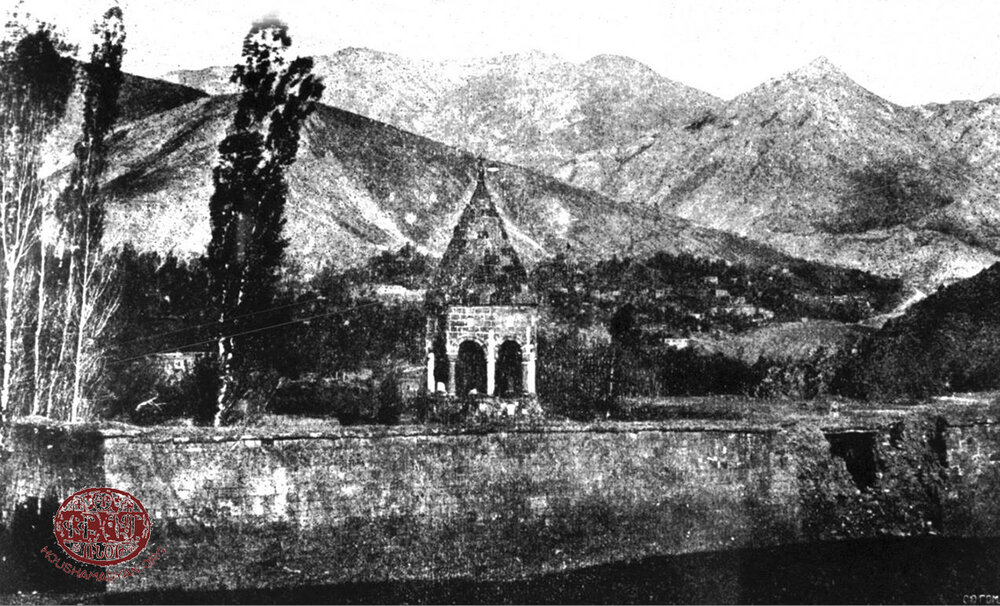

The Saint Hovhannes Monastery of Teghoud

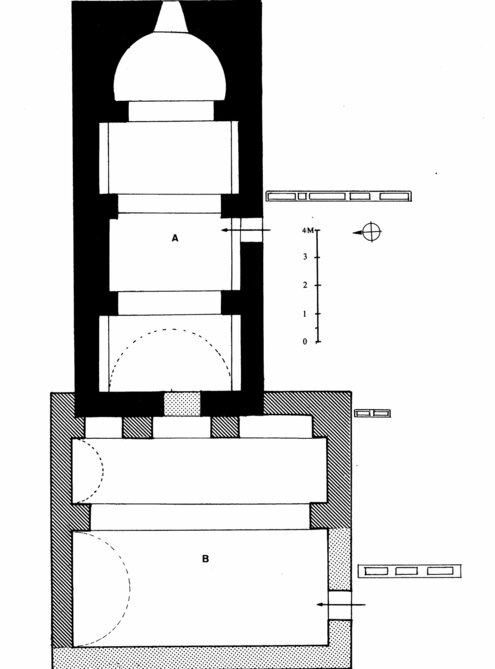

It was located in the subdistrict of Khlat, about 20 kilometers southwest of the city of Khlat, at the foot of Mount Nemrout. The monastery was known for the beauty of its surroundings and the view of Lake Sevan that it offered: “The Sea of Van, its islands, and the Mogats, Shadakh, Vosdan, and Varak mountains are all lined up before one’s eyes… It sits like a queen in a cloud-capped forest of poplars and teghogh trees, which greatly enhance its illustrious presence,” wrote Bishop Arisdages Devgants, who visited the monastery in 1878. [66]

Aside from the main church, the monastic complex included an old and unattractive chapel, a two-story guesthouse with eight to ten rooms, the prelacy building, a hayloft, and other buildings. [67]

The monastery thrived in the late 16th century, under the leadership of Abbot Adom (manuscripts copied at the monastery during this period have survived to the present time). [68]

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Saint Hovhannes Monastery of Teghoud was the only monastery in the Paghesh Diocese with a functioning monastic order. In 1878, 23 monks, fieldhands, shepherds, and guards lived on the premises. The monastery owned 200 sheep, 25 oxen, 18 cows, four mules, 16 cattle, nine donkeys, two horses, etc. [69] The abbot was Father Ghazar, who was a wizened 113-year-old, and who “would stand shaking and mute in one corner of the monastery, but who with his words, orders, and the influence he once wielded as a young man was able to govern the institution and its properties.” [70]

On the eve of the Genocide, the abbot of the monastery was Father Hamazasb. [71]

The Holy Mother-of-God Monastery of Madnavank

Also known as the Madnavank Monastery. It was located three to four kilometers southwest of the city of Khlat, near the settlements of Madnavank and Kharabashar. [72] According to tradition, it has been built by the apostle Thaddeus, at a site that was pointed out to him by an angel who had descended from heaven (which explains the origin of the monastery’s name [mad is Armenian for “finger”]). [73]

Near the monastery was a boulder engraved with a cross, called Tivagoul, sitting atop springs of cold water. [74]

Manuscripts copied at the monastery in the 15th to 17th centuries have been preserved. [75]

There is little information on the history of the monastery in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Sources indicate that it was standing, but evidently it lacked an order. [76]

Abandoned and Derelict Monasteries

The Saint Yezdipouzd (Saint Yizdipouzid) [77] Monastery

In the words of K. Srvantsdyants, this “beautiful” and “sea-facing” [78] monastery was located 20 kilometers southeast of the city of Paghesh, near the Armenian village of Toukh, close to the shores of Lake Van.

By the mid-19th century, the monastery was already abandoned and derelict. Its church was described as “built entirely of stone, beautiful, and with five immaculate altars.” Beside the church was a derelict chapel, also built of stone. The monastery complex was surrounded by a dilapidated stone wall. [79]

The lands of the monastery had been taken over by the villagers of Toukh, who treated them as their own. [80]

The Monastery of Anania the Disciple

In historical records, this monastery was also known as the Holy Commander or Saint Kevork Monastery. It was located near the Amrdolou Saint Hovhannes. [81] It reached its heyday in the 15th-17th centuries, when it was home to a repository and when its monks were engaged in copying manuscripts. [82]

The Saint Hovhannes Monastery

It was located near the Armenian-populated village of Eroun (Sarageole), 20 kilometers northeast of Paghesh. By the mid-19th century, it was abandoned and in ruins. [83]

The Saint Kevork Monastery

It was located about 15 kilometers west of the city of Paghesh, near the village of Trtsink (Vortsenk?) of Modgan. [84] In the mid-1890s, it was still standing, but abandoned. There were more than 200 walnut trees in the vicinity of the monastery. Pilgrims would gather and eat the walnuts only at the site, but refrain from taking them home, as it was believed that those who did would invite misfortune upon themselves. [85]

The Saint Taniel Monastery

It was located in the Ashbner (Asbuncher) village of Modgan. In the late 19th century, it was a well-known pilgrimage site. [86]

The Saint Giragos Monastery

It was located near the village of Kghekh in Modgan. In the late 19th century, it was a celebrated pilgrimage site. On the Holiday of Vartavar, both Armenians and Kurds would visit the monastery and offer animal sacrifices. [87]

The Holy Mother-of-God Monastery of Dzghag

It was located near the Armenian-populated settlement of Dzghag in the subdistrict of Khlat. Two manuscripts of the Bible, copied at the monastery in the 15th-16th centuries, were kept there. [88]

At the end of the 19th century, the monastery was still standing, but abandoned. Its fields were cultivated by local villagers. [89]

The Mousg (Housg) Monastery

It was located near the settlement of Chrhor in the subdistrict of Khlat. In the late 19th century, it was in ruins and served as a pilgrimage site. [90]

The Kevork Monastery

It was located near the Armenian-populated settlement of Shamiram. In the late 19th century, it was still standing, but abandoned. [91]

The Shekhis Monastery

It was located near the city of Paghesh (the exact location is unknown). By the late 1890s, it had long been abandoned and had fallen into disrepair. In historical sources, it is often mentioned alongside the nearby Saint Sion Church-Monastery, which was also in ruins. [92]

The Churches of the Paghesh Diocese

The Churches of the City of Bitlis (Paghesh)

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the city of Paghesh consisted of four distinct neighborhoods, each separated from the others by a distance of 1.5 to two kilometers. In the north of the city was the Taghi Kloukh neighborhood, in the east the Dzabrgor neighborhood, in the southeast the Avermeydan neighborhood, and in the southwest the Komats or Dash Mouhale neighborhood. [93] Armenians and Muslims lived together in these districts, with Armenians outnumbering Muslims to a certain extent in the Taghi Klough and Avermeydan neighborhoods. [94]

In the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, there were four Armenian churches in the city of Paghesh: the Garmrag Saint Nshan Church in the Taghi Kloukh neighborhood; the Saint Sarkis and Five-Altar Holy Mother-of-God churches in the Dzabrgor neighborhood; and the Saint Kevork Church in the Avermeydan neighborhood. The Komats neighborhood did not have its own church. Its Armenian residents attended the church of the Amrdolou (Amlorto) Saint Hovhannes Monastery, which was located within the boundaries of the neighborhood [95] (for this reason, some sources include Saint Hovhannes in the list of the churches of Paghesh, putting the number of churches in the city at five [96]). Initially, the seat of the diocesan prelacy was the Amrdolou Monastery, but it was moved to the Garmrag Saint Nshan Church in the late 1870s. [97]

The churches of the city were described as “sturdy and quite beautiful,” as well as “well-furnished.” [98]

The city’s churches generated income from the stores and other buildings that were donated or endowed to them, donations collected during services, and fees paid for various religious ceremonies (baptisms, requiems, etc.).

The Garmrag Saint Nshan Church

The Garmrag Saint Nshan Church was the seat of the prelacy of Bitlis. It was renovated in 1845. It was built of soft, polished blocks of stone, in the style of a basilica, with six columns. It was crowned with a small steeple. [99]

The church was also known by the name of Saint Giragos, which had been its initial name. It was renamed the Garmrag Saint Nshan [Sanguine Holy Sign] when a fragment of the True Cross was brought to the church, where it was kept in a small, square, silver case adorned with precious red gems. According to popular legend, the gems had turned red from the blood of Christ. This relic was venerated so much that even the local Turks and Kurds would swear “Garmrag hakhi ichoun” – “On the blood of the Garmrag Cross.” [100]

A relic from Saint Sdepanos (Saint Stephen the Martyr) was kept at the church. [101]

In the 1890s, the church owned ten homes and seven stores, which generated an income of 80 to 100 pounds per year. [102]

On the eve of the Genocide, the serving priest of the church was Father Khachadour Der-Hagopian. [103]

The Saint Sarkis Church

It was located in the Dzabrgor neighborhood of the city, in the market square. [104]

Beneath the main altar of the church was an underground spring, from which fresh water flowed into reservoirs and was then distributed to the various neighborhoods of the city. [105]

On the eve of the Genocide, the serving priest was Father Kevork Der-Kevorkian. [106]

The Five-Altar Holy Mother-of-God Church

It was located across the Saint Sarkis Church, only 200 meters away from it. [107] It had two side altars on each side of the main altar, which had inspired its name. [108] The church was described as “small” and “elegant.” [109]

On the eve of the Genocide, the serving priest of the church was Father Mgrdich Der-Kevorkian (the brother of Kevork Der-Kevorkian, the serving priest of the Saint Sarkis Church). [110]

The Saint Kevork Church

It was located in the Avermeydan-Haynots neighborhood of Bitlis. [111] It was a large building, and for that reason, its income was barely enough to cover its expenses. [112]

On the eve of the Genocide, the serving priests of the church were Father Ghevont Bahlavouni and Father Movses Gulgezian. [113]

The Churches of the Armenian-Populated Villages/Settlements of the Paghesh Diocese

Below, we present a list of the churches in the Armenian-populated villages and settlements of the Paghesh Diocese up to the eve of the Armenian Genocide. The populations of and number of churches in each settlement are provided per the 1913 census conducted by the Paghesh diocesan authorities on behalf of the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate. [114] The names of the churches are provided per the list prepared by Bishop Arisdages Devgants in 1878 [115]; the list that appeared in the 1903 Calendar of the Saint Savior Armenian Hospital (which was based on a diocesan survey conducted by order of Maghakia Ormanian, Patriarch of Constantinople, in 1902) [116]; Teotig’s Koghkota (1915) [117], and other sources. In cases where different sources disagree on the name of a church, we have provided both names and have noted the applicable date of that information in parentheses: 1878 (Devgants), 1903 (1903 Calendar), or 1915 (Teotig).

The names of the churches in the Armenian-populated villages of Modgan [118] are provided per Arisdages Devgants [119] and Vartan Bedoyan. [120]

The names of the serving priests of the churches are provided per Teotig.

Subdistrict of Bitlis, Villages of the Tadvan Region

The region of Tadvan stretched east and northeast of the city of Paghesh. It included Armenian-populated villages stretching all the way to Lake Van.

Alamek

4 households, 28 Armenians.

The Saint Garabed Church (1903) or the Saint Sarkis Church (1878, 1915).

Aghktsor

9 households, 53 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church (1903).

Papshen

50 households, 490 Armenians.

The Saint Haroutyun Church (1881) [121] or the Holy All-Savior-Saint Haroutyun Church (1915). Serving priest: Father Markar Garabedian.

In the east of the village was a chapel and pilgrimage site, called Lousabdough Saint Sahag, which “was visited by those suffering from pain in the eyes, and who were often cured thanks to their piety.” [122]

Tadvan

135 households, 1,298 Armenians.

Tadvan was located on the western shore of Lake Van and was well-known for its port, through which it maintained constant contact with the city of Van. The village church was called Saint Teotoros. In the early 1880s, it was described as “plain, with a very insignificant status.” [123] A church called Saint Sarkis is also mentioned in sources, as well as five holy sites in ruins. [124] In 1915, the serving priest of Saint Teotoros was Father Tateos Der-Tateosian.

Toukh

50 households, 349 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church. The Saint Yizdipouzdi Monastery was also near the village.

Khakhrev

39 households, 370 Armenians.The Saint Hagop Mdzpnatsi Church. [125]

Dzvar

20 households, 180 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church (1878) or the Holy Mother-of-God Church (1903). A pilgrimage site, called Avak Khach, was located in the east of the village. [126]

Gamakh

49 households, 423 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (1881) [127] or the Forty Martyrs Church (1903; 1915). Serving priest: Father Yeghishe Der-Manouelian.

Mezre

30 households, 155 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (1878).

Bor

59 households, 524 Armenians.

The Saint Anania Church (1915) [128]. Serving priest: Father Giragos Der-Giragosian.

Ourdap

88 households, 584 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork and Holy Mother-of-God churches (1903).

Bitlis Subdistrict. Villages of the Parkhant Region

The region of Parkhant was located south of the city of Bitlis, stretching into the plains of the upper basin of the Paghisho Chour River.

Amb

7 households, 23 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (1903). The chapel/pilgrimage site of Saint Hagop Dyarneghpayr was also near the village. [129]

Khartgogh

11 households, 199 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (1903).

Khmblchour (Khmelchour)

15 households, 62 Armenians.

The Saint Andon Church (1903; 1915). [130]

Gorvou Verin

64 households, 527 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church and the Saint Hovhannes Church (1903). [131] Serving priest: Father Mardiros Krikorian.

Gorvou Vari

31 households, 235 Armenians.

The Saint Heghine Church. [132]

Hormz (Heomuz)

23 households, 130 Armenians.

The Saint Krisdapor Church (1903).

Markork

28 households, 173 Armenians.

The Saint Boghos-Bedros Church (1878) or the Saint Kevork Church (1881; 1903).

Parkhant

40 households, 230 Armenians.

The Saint Giragos Church (1878) or Saint Adom Church (1903). [133]

Bitlis Subdistrict. Villages of the Aznvatsor (Keozaltara) Region

The Aznvatsor or Keozaltara region was located east of the city of Paghesh, in the foothills of the mountains to the south of Lake Van.

Khart

10 households, 88 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (1915).

Garp

56 households, 384 Armenians.

The Saint Krikor Lousavorich Church (1878) or the Saint Simeon Church (1903; 1915). Serving priest: Father Srabion Mardirosian.

At the church were kept 15 manuscripts of the Bible, four silver-bound printed Bibles, and 12 silver crosses. [134]

Godom (Gadom)

4 households, 39 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church (1903). [135]

Hant

50 households, 321 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church (1878) or the Saint Sdepanos Church (1903).

Hortsak (Hortsoug)

17 households, 56 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church (1878) or the Holy Cross Church (1903).

Nel

36 households, 232 Armenians.

The Saint Hovhannes Church. The ruins of the Saint Haroutyun Monastery were located southeast of the village. [136]

Sak

72 households, 406 Armenians.

The Toukhmanoug Church (1878) or the Saint Kevork Church (1903).

Dashdop

15 households, 100 Armenians.

The Saint Hovhannes Church (1903).

Dop

31 households, 224 Armenians.

The Saint Garabed Church (1878) or the Saint Sarkis Church (1903; 1915). Serving priest: Father Mesrob Markarian.

At the church were kept two manuscripts of the Bible and a handwritten medical book, two silver chalices, a gold cross, etc. [137]

Bitlis Subdistrict. The Villages of the Dadig Region

The region of Dadig was located southeast of the city of Paghesh, in the foothills of the Armenian Taurus Mountains.

Khoultig

490 households, 2,598 Armenians.

This village was the administrative center of the Dadig region.

The Saint Kevork Church (described as “built of stone” and “large” [138]). The serving priests were Father Hovhannes Mihranian and Father Kevork Der-Markarian.

Dzghgam

50 households, 277 Armenians.

The Saint Teotoros Church. The ruins of the Holy Mother-of-God Monastery were in the vicinity of the village.

Gelhog

30 households, 162 Armenians.

The Saint Bedros Church (1878) or Saint Kevork Church (1903).

Gerkh (Gekhr)

20 households, 191 Armenians.

The Saint Yeghishe Church. The church building was described as “gloomy” and “squalid.” [139] According to K. Srvantsdyants, the villagers attributed miraculous healing properties to the church: “Our Saint Yeghishe is mighty, and he comes to our aid against all dangers. We see him both in our dreams and in broad daylight… He rides a red horse, wears armor, has a white beard, and is an ascetic.” [140]

Modjgonk

39 households, 292 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (1878); the Holy Mother-of-God and Saint Hovhanness churches (1903); or the Holy Mother-of-God Church (1915). In 1915, the priest of the Holy Mother-of-God Church was Father Simon Der-Simonian.

Vosdin

31 households, 224 Armenians.

The Saint Lousavorich Church (1878) or the Saint Kevork Church (1903).

Bas

60 households, 351 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church (1878) or the Saint Kevork and Holy Mother-of-God churches (1903).

Vanig

61 households, 380 Armenians.

The Holy Cross Church (1878) or the Saint Kevork Church (1915). Serving priests: Father Parsegh Der-Parseghian and Father Anania Der-Minasian.

Sasig

28 households, 193 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church (1878) and the Holy Mother-of-God Chapel (1878, 1903).

The Khlat Subdistrict

The Khlat Subdistrict was located on the northwestern shores of Lake Van. It included a portion of the historical subdistrict of Pznounik of the land of Darouperan of Greater Hayk. On the northeastern borders of the subdistrict rose Mount Sipan, and in the south rose the mountains Kurkour and Nemrout.

Akrag

21 households, 152 Armenians.

The Three-Altar Holy Mother-of-God Church.

Aghagh

30 households, 270 Armenians.

On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, the Armenian population of the village was entirely Protestant.

Ersonk

42 households, 397 Armenians.

The Saint Teotoros Church. Serving priest: Father Hovhannes Der-Hagopian.

Teghoud

260 households, 1,599 Armenians.

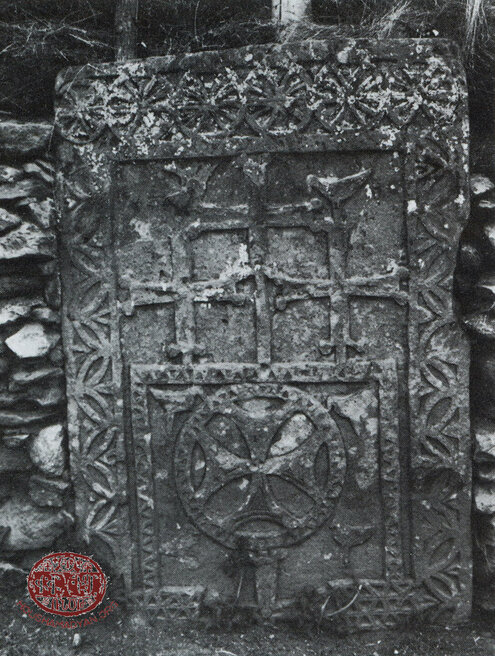

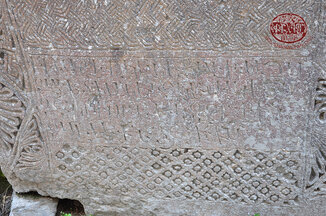

The Saint Sdepanos and Saint Kevork churches. Teotig only mentions the Saint Sdepanos Church, where the serving priests were Father Mgrdich Bulbulian, Father Hamazasb Djeroyan, and Father Vartan Manougian.The village was also home to beautiful cemetery and an upright khachkar (cross-stone; stele) called Tsasman Khach [Cross of Agony].

Kharabashehir (Kharabashar)

38 households, 210 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church; serving priest: Krikoris Jamharian. The Saint Nigoghos Church, serving priest: Father Movses Garabedian. [141]

Khoulig

68 households, 670 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church. Serving priest: Father Nahabed Asdvadzadourian.

Dzaghge

29 households, 209 Armenians.

The Saint Taniel Church.

Dzghag

159 households, 1,394 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God and Saint Kevork churches (1878); or the Saint Hovhannes Church (1903); or the Saint Sdepanos Church (1915). Serving priest: Father Daniel Haroutyunian.

The village was also home to a Protestant community, led by Reverend Asadour Kevorkian.

Garmoundj (Gamourdj)

100 households, 724 Armenians.

The Saint Daniel and Holy Mother-of-God churches, both served by Father Krikoris Shadoyan.

Gdzvag

150 households, 940 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church. Serving priest: Father Sahag Mikayelian.

Goshdian

97 households, 636 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church (1878) or the Saint Nigoghayos Church (1903).

Tsorgonk

59 households, 674 Armenians.

The Saint Nerses Church (1878).

Djemaldin

34 households, 175 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church. [142]

Madnavank

28 households, 170 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church (1903).

Medzk

132 households, 1,404 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church. Serving priest: Father Antreas Boghosian.

Shamiram

58 households, 440 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church.

Chzirok

10 households, 115 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church (1878) or the Saint Minas Church (1903).

Chrhor

50 households, 326 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church (1878).

Spratsor

50 households, 360 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church. Serving priest: Father Ghazar Kasbarian.

Sokhort

49 households, 386 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church. Serving priest: Father Boghos Vartabedian.

Dapavank

100 households, 670 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church. The serving priests were Father Parsegh Vartanian, Father Ghougas Der-Hovsepian, and Father Shmavon Zagharian.

Prkhous

207 households, 1,939 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church. It was described as having been “built of polished black stone, beautiful and elegant, and unrivaled in the district.” [143] In 1915, the serving priest was Father Haroutyun Ghougasian. [144]

Several manuscripts of the Bible were kept in the village, one of which, called Garmir Gogh, was visited by pilgrims seeking cures for various ailments. [145]

Four-five households of Armenian Protestants lived in Prkhous, “who sometimes lecture the people and preach ‘piety’ in their own language.” [146]

Modgan Region

Modgan was located west of Paghesh. Its position made it a natural part of Sassoun. It was within the borders of the historical Kzekh District of the land of Aghtsnik of Greater Hayk.

Asbncher (Upper and Inner)

35 households, 526 Armenians.

The Toukhmanoug Church (Upper Asbncher) and the Saint Sdepanos Church (Inner Asbncher) (arched, standing).

Puroudk

27 households, 155 Armenians.

The Saint Hagop Church (1878).

Poghnoud

20 households, 300 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church.

Khour

13 households, 105 Armenians.

The Saint Echmiadzin Church.

Gundzou

49 households, 500 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church.

Marmant

3 households, 11 Armenians.

Two churches, both in ruins.

Mere Taghi

7 households, 73 Armenians.

The Saint Krisdapor Church.

Muzoug (Mzonk)

16 households, 188 Armenians.

The Saint Sdepanos Church.

Mutsi

30 households, 300 Armenians.

The Saint Sarkis Church (arched, standing).

Murtsank

5 households, 50 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church.

Nich (Niz)

25 households, 200 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork and Saint Sarkis churches. [147]

Shen (Shenig)

50 households, 500 Armenians.

The Holy Mother-of-God Church (arched, standing).

Vortsenk

10 households, 90 Armenians.

The Saint Kevork Church.

Slundr (Sghount)

30 households, 400 Armenians.

The Saint Hagop Church (arched, standing).

Kashakh

27 households; 600 Armenians.

The Saint Hagop Church (arched, standing).

- [1] The Modjgonits Holy Mother-of-God and the Mrorsa Saint Tovmas are also included among the monasteries of the Paghesh Diocese by the 1904 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1904 Expanded Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital] (Constantinople, 1903, p. 374). The Modjgonits Holy Mother-of-God is not mentioned at all by other sources (D. Balian, H. Vosgian, etc.). However, we know that there was a Holy Mother-of-God Church in Modjgonk, and we can assume that its listing as a monastery was an oversight. As for the Mrorsa Saint Tovmas, according to Ottoman administrative divisions, it was located in the Gardjgan Subdistrict of Van Province, and other sources list it among the monasteries of the Rshdounyats District (see, for example, Hamazasb Vosgian, Vasbouragan-Vani Vankeru [The Monasteries of Vasbouragan-Van], Part A, Vienna, 1940, pp. 155-158).

- [2] For the history of the monasteries of Paghesh in this era, see Father H. Nerses Aginian, Pagheshi Tbrotsu 1500-1704 [The School of Paghesh 1500-1704], Vienna, 1952, p. 396.

- [3] M. Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag Kavars Arevelyan Dadjgasdani: Deghakroutyunk Saren yev Tsoren, Hnen yev Noren Bidani Kidnots [Accounts of Travels across the Armenian-Populated Provinces of Eastern Turkey: Topography of the Mountains and Valleys, Useful Information on the Old and the New], Part A, Constantinople, 1884, p. 58.

- [4] G. S. Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh,” Artsakank Literary and Political Daily, Tbilisi, 19 (30) December 1897, p. 3. The author also decried the fact that the condition of the manuscripts that had once been in the monastery’s repository was unknown, as they were under lock and key and in the possession of a private individual, inaccessible even to the prelate of the diocese (ibid.).

- [5] Father Papken, “From Moush to Bitlis,” Puzantion Armenian Daily, Constantinople, 17 (30) July 1900, number 1148, p. 1.

- [6] “Paghesh and its Surroudings,” Louma Literary Review, fifth year, Tbilisi, Book A, January 1900, p. 208; Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag Kavars Arevelyan Dadjgasdani…, p. 58.

- [7] Specifically, see the letter from Father Yeghishe Chilingirian, prelate of Paghesh, to Father Yezras Sachlian, in “The Monasteries of Paghesh,” Puzantion Armenian Daily, Constantinople, 30 March (12 April) 1900, number 1056, pp. 1-2. Also see “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh,” Arevelk National, Literary, and Political Daily, Constantinople, 31 December (12 January) 1899 (1900), number 4211, p. 1; and Father Papken, “From Moush to Bitlis,” Puzantion Armenian Daily, Constantinople, 17 (30) July 1900, number 1148, p. 1.

- [8] Hamazasb Vosgian, “Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” Monthly Review, Armenian Studies Digest, Year 18, January-December 1944, number 1-12, p. 79.

- [9] Bishop Drtad Balian, Hay Vanorayk [Armenian Monasteries], Echmiadzin, 2008, p. 239; Vosgian, “Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 86.

- [10] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 239.

- [11] N., “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh,” Arevelk National, Literary, and Political Daily, Constantinople, 31 December (12 January) 1899 (1900), number 4211, p. 1.

- [12] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878 [Visit to Armenia 1878], text prepared and annotated by H. M. Boghosian, Yerevan, 1985, p. 101; Bishop Karekin Srvantsdyants, Hamov Hodov, Volume A, Third Edition, Paris, 1949, p. 111.

- [13] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 101.

- [14] “Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 208.

- [15] N., “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh;” Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 239.

- [16] Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 86.

- [17] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 239.

- [18] Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [19] Archives of the Museum of Literature and Art (MLA), T. Azadian Fund, part 3, item 40/III, numbers 1-3 (Census of Paghesh); Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 101.

- [20] Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 93.

- [21] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 232.

- [22] N., “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [23] T. K. Gerdmenchian, “The City of Paghesh and Its Churches,” Historical-Oratorical Review, 1990, n. 1, p. 119.

- [24] Refers to a manuscript copied in the Amrdolou Monastery of Paghesh in 1672 that contained Ghazar Parbetsi’s History of Armenians, and which is now kept at the Mesrob Mashdots Repository (Madenataran). According to K. Der-Mgrdchian, an expert in Armenian studies, this manuscript “is the only surviving original manuscript that has served as the basis of the rest… The others are all copies” (see Kevork Der-Vartanian, “The Armenian History of Ghazar Parbetsi and the Bibliography of Manuscripts,” Echmiadzin, 2016, number 8, p. 79). For more on Vartan Paghishetsi’s interest in historical literature and his efforts to collect and copy the works of Armenian historians, see Aginian, Pagheshi Tbrotsu 1500-1704, pp. 275-285.

- [25] A. Matevosian, “The School of the Amrtolou Monastery,” Haygagan Sovedagan Hanrakidaran [Armenian-Soviet Encyclopedia], Volume 2, Arkishdi-Keghervan, p. 333.

- [26] Mgo, “The Province of Paghesh,” Artsakank Literary and Political Weekly, Tbilisi, 17 October 1882, n. 35, p. 544.

- [27] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 233.

- [28] Ibid.

- [29] MLA, T. Azadian Fund, part 3, item 40/III, numbers 1-3.

- [30] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 233.

- [31] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 100.

- [32] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 234.

- [33] For a list of the manuscripts kept in the monastery in the early 17th century, see “Father Vartan Paghishetsi: List of the Books of the Amrtolou Monastery,” Ararad Monthly, Vagharshabad, February-March 1903, pp. 176-189. K. Srvantsdyants, who visited the monastery in the early 1880s, referring to the repository and its reputation, stated that he was only able to see the manuscripts that were “brought out,” meaning the ones that were used during church services (K. V. Srvantsdyants, Toros Aghpar [Brother Toros], Constantinople, K. Baghdadlian Printing House, 1885, p. 262). Other writers also complained of the inaccessibility of the repository’s manuscripts (Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh”).

- [34] Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [35] Vaverakrer Hay Yegeghetsou Badmoutyan. Kirk 22. Mgrdich A. Khrimian Gatoghigos Amenayn Hayots (1892-1907). Mas B. Pasdatghteri Joghovadzou [Records of the History of the Armenian Church. Book 22. Mgrdich I Khrimian, Catholicos of All Armenians (1892-1907). Part B. Compendium of Documents], compiled by K. Avakian, edited by A. Virapian, Echmiadzin, 2020, pp. 655-656. We do not know if the monastery was ever repaired after the earthquake. Other Armenian institutions that were “partially destroyed” alongside adjacent buildings and the estates they owned included the Khntragadar, Avekhi, and Komats monasteries; as well as the Saint Sarkis, Five-Altar, and Saint Kevork churches (ibid.).

- [36] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev Ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin [The Calvary of the Armenian Clergy and Its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915], Second Edition, Tehran, 2014, pp. 96-97.

- [37] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 97; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 82.

- [38] Gerdmenchian, “The City of Paghesh and Its Churches,” p. 122.

- [39] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 237.

- [40] N., “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh;” Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 237; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 82.

- [41] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 237; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 82.

- [42] MLA, T. Azadian Fund, part 3, item 40/III, numbers 1-3; Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 100

- [43] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 100.

- [44] “The Overall State of Paghesh,” Armenia Newspaper, National, Political, etc., Marseille, year 8, number 41, 7 January 1893, p. 1.

- [45] N., “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh;” Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 237

- [46] Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [47] Gerdmenchian, “The City of Paghesh and Its Churches,” p. 124.

- [48] Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 81.

- [49] N., “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh;” Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 238.

- [50] N., “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [51] MLA, T. Azadian Fund, part 3, item 40/III, numbers 1-3; Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 100.

- [52] N., “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [53] Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [54] “Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 207; N. “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [55] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 238.

- [56] Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 68.

- [57] Father Nerses Sarkisian, Deghakroutyunk i Pokr yev i Medz Hayk [Travels in Greater and Lesser Hayk], Venice, 1864, p. 249.

- [58] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 242.

- [59] Ibid., p. 243.

- [60] Srvantsdyants, Hamov Hodov, Volume A, p. 111; Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 242; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 95.

- [61] Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 96.

- [62] MLA, T. Azadian Fund, part 3, item 40/III, numbers 1-3; Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 101.

- [63] “Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 207; Srvantsdyants, Hamov Hodov, volume A, p. 111.

- [64] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 242.

- [65] MLA, T. Azadian Fund, part 3, item 40/III, number 1; Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 100.

- [66] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 88.

- [67] Ibid.

- [68] H. Hamazasb Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankeru [The Monasteries of Daron-Darouperan], Vienna, 1953, pp. 130-131.

- [69] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 88.

- [70] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag…, p. 90.

- [71] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 88.

- [72] Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Daron-Darouperan,” p. 254; Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 92.

- [73] Sarkisian, Deghakroutyunk i Pokr yev i Medz Hayk, p. 272.

- [74] T. Kh. Hagopian, Sd. D. Melik-Pakhshian, and H. Kh. Parseghian, Hayasdani yev Haragits Shrchanneri Deghanounneri Pararan [Dictionary of Place Names of Armenia and its Environs], Volume 3: G-N, Yerevan, 1991, p. 714.

- [75] For quotes from these manuscripts, see Vosgian, Daron-Darouperani Vankeru, pp. 255-257.

- [76] The Monasteries of Paghesh,” Ararad, Official Pastoral Monthly of the Mother See of Holy Echmiadzin, Vagharshabad, July 1898, p. 300.

- [77] Yezdipouzd or Yizdipouzid was a Persian monk who converted to Christianity in Dvin in 552 A.D., and was consequently condemned to death by a Persian governor. He is considered a saint by the Armenian Church. His martyrology has been preserved. His name, in the Pahlavi language, translates into “God has saved” or “God has given life” (for details, see Garen Hovhannisian, “Saint Yizdpouzid, Saint Tavit Tvnetsi, and Toukh Manoug,” Echmiadzin, October 2018, pp. 68-69).

- [78] Srvantsdyants, Hamov Hodov, volume A, p. 52.

- [79] Sarkisian, Deghakroutyunk i Pokr yev i Medz Hayk, p. 250.

- [80] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 243; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 82.

- [81] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 241.

- [82] Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 79.

- [83] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 243; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 95.

- [84] Other sources don’t mention a settlement called Trtsink in Modgan. Possibly, this was the village of Vortsenk (see Patalian, “The Historical-Demographic Situation of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Genocide. Part Eight. The Historical and Geographic Province of Sassoun and the City of Paghesh (Bitlis),” VEM Pan-Armenian Review, 2017, number 2 (58), Supplement, p. XXIV).

- [85] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 243.

- [86] Ibid.

- [87] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 244; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 94.

- [88] Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 93.

- [89] Balian, Hay Vanorayk, p. 244.

- [90] Ibid.

- [91] Ibid.

- [92] D. V. Balian, “Armenian Monasteries,” Puzantion Armenian Daily, Constantinople, 20 December (1 January) 1898, number 351; Bishop Drtad Balian, “Armenian Monasteries – 12,” Puzantion Armenian Daily Newspaper, Constantinople, 25 May (7 June) 1900, number 1103; “The Monasteries of Paghesh,” Ararad, Official Pastoral Monthly of the Mother See of Holy Echmiadzin, Vagharshabad, July 1898, p. 300; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 95.

- [93] “Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 207.

- [94] Ibid.

- [95] Ibid., p. 208; also see A-To, Vani, Bitlisi, yev Erzurumi Vilayetneru [The Vilayets of Van, Bitlis, and Erzurum], Yerevan, Cultura Publishing, 1912, p. 83.

- [96] S. M. Dzotsigian, Arevmdahay Ashkharh [The Western Armenian World], New York, 1947, p. 131.

- [97] “Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 208.

- [98] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag…, p. 56; Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [99] Mgo, “The Province of Paghesh.”

- [100] According to a different tradition, the church had obtained its name from the figure of a dove, carved in red stone (soudag), which sat atop the steeple in lieu of a cross. The stone had turned red both due to its age and the smoke of the countless candles (the carved dove had survived from a pagan temple that had stood at the site before the adoption of Christianity (Inka Avakian, 1915i Bitlisian Voghperkoutyun. Mihran Gazariani Houshabadoumu [The Tragedy of Bitlis of 1915. Mihran Gazarian’s Memories], Gyumri, Tbir Printing House, 2008, p. 7).

- [101] Mgo, “The Province of Paghesh.”

- [102] Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [103] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 90.

- [104] Avakian, 1915 t. Bitlisyan Voghperkoutyun, p. 7.

- [105] Mgo, “The Province of Paghesh.”

- [106] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 90.

- [107] Avakian, 1915 t. Bitlisyan Voghperkoutyun, p. 7.

- [108] Mgo, “The Province of Paghesh.”

- [109] Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [110] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 90.

- [111] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 89.

- [112] Toukhmanian, “The Churches and Monasteries of Paghesh.”

- [113] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 89.

- [114] AGBU Noubarian Repository Archive, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff. 49-52 (Paghesh and Khlat), f. 60 (Modgan). Also see Kévorkian, Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman…, pp. 469-471 (Bitlis/Paghesh), pp. 472-474 (Khlat), and p. 477 (Modgan).

- [115] MLA, T. Azadian Fund, part 3, item 40/III, numbers 1-3 (Census of Paghesh); also see Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 101, pp. 87 (Khlat), 99, 103-104 (Paghesh), and 106 (Modgan).

- [116] 1903 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots, pp. 335-337.

- [117] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, pp. 91-98 (Paghesh and Khlat) and p. 127 (Modgan).

- [118] Only includes the Armenian-populated settlements of the Paghesh Diocese per Teotig’s list (Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 127).

- [119] Devgants, Aytseloutyun i Hayasdan 1878, p. 106.

- [120] Vartan Bedoyan, Sassouni Parparu [The Dialect of Sassoun], Yerevan, 1954, pp. 180-182; Vartan Bedoyan, Sassoun, Yerevan, Nakhapem Publishing, 2016, pp. 71-74.

- [121] It was located in the west of the village and described as “gorgeous” (“Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 214).

- [122] Ibid.

- [123] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag Karavs Arevelyan Dadjgasdani…, p. 81.

- [124] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 94.

- [125] The 1881 report mentions the Saint Sahag Church (“Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 214), which K. Patalian described as “derelict” (Kegham M. Patalian, “The Historical-Demographic Situation of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Genocide. Part Six. The Northern, Eastern, and Western Districts of Paghesh Province,” VEM Pan-Armenian Review, 2016, 3 (55), Supplement, p. XXVII).

- [126] “Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 213.

- [127] Described as a “small, stone-and-lime” building, in the northwest of the village (“Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 213).

- [128] The report prepared by the Diocesan authorities of Paghesh in 1881 mentions the Saint Haroutyun Church in the southwest of the village (“Paghesh and Its Environs,” pp. 212-213). According to information from 1903, the name of the church of the village of Bor was the Holy Mother-of-God.

- [129] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 98.

- [130] The 1881 report also mentions a church in the west of the village, called Saint Hagop (“Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 211).

- [131] According to the report prepared by the Diocese of Paghesh in 1881, Saint Hovhannes was originally a monastery. The church building was described as “gorgeous,” but it was also said that “chaos reigned” within (“Paghesh and its Environs,” p. 211).

- [132] According to K. Patalian (The Historical-Demographic Situation of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Genocide. Part Seven. The Southeastern Districts of Paghesh Province,” VEM Pan-Armenian Review, 2016, 4 (56), Supplement, p. VI).

- [133] The report prepared by the Diocesan authorities of Paghesh in 1881 mentions a church called Saint Andonyants (Saint Adomvyants?) in the south of the village; and the ruins of the Saint Hagop Church in the north of the village (“Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 210; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 95).

- [134] Hayots Tseghasbanoutyunu Osmanian Tourkyayoum. Verabradznerou Vgayoutyunner. Pasdatghteri Joghovadzou [The Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey. Testimonies of Survivors. Compendium of Documents], Volume II, The Province of Bitlis, K. Avakian (author and compiler), A. Virapian (chief editor), Yerevan, National Archives of Armenia, 2012, p. 71.

- [135] According to K. Patalian, the church had been turned into a mosque in the 1870s (The Historical-Demographic Situation of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Genocide. Part Seven. The Southeastern Districts of Paghesh Province,” p. III).

- [136] “Paghesh and Its Environs,” p. 231; Vosgian, “The Monasteries of Salnatsor-Paghesh,” p. 95.

- [137] Hayots Tseghasbanoutyunu Osmanian Tourkyayoum: Verabradzneri Vgayoutyunner…, p. 76.

- [138] Srvantsdyants, Hamov Hodov, volume A, p. 114.

- [139] Srvantsdyants, Hamov Hodov, volume A, p. 115.

- [140] Ibid.

- [141] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 91.

- [142] Kegham Patalian, “The Historical-Demographic Situation of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Genocide. Part Six. The Northern, Eastern, and Western Districts of Paghesh Province,” p. XXV.

- [143] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag Karavs Arevelyan Dadjgasdani…, p. 93.

- [144] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 91.

- [145] Hayots Tseghasbanoutyunu Osmanian Tourkyayoum: Verabradzneri Vgayoutyunner…, p. 57.

- [146] Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag Karavs Arevelyan Dadjgasdani…, p. 93.

- [147] According to K. Patalian (Patalian, “The Historical-Demographic Situation of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Genocide. Part Eight. The Historical-Geographic Province of Sassoun and the city of Paghesh (Bitlis),” VEM Pan-Armenian Review, 2017, number 2 (58), Supplement, p. XXIV).