Churches and Monasteries (Part I)

Bitlis (Paghesh) – Religious Life

Author: Robert Tatoyan, 18/07/2023 (Last modified: 18/07/2023) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Structure of the Paghesh Diocese and its Development in the Pre-Genocide Era

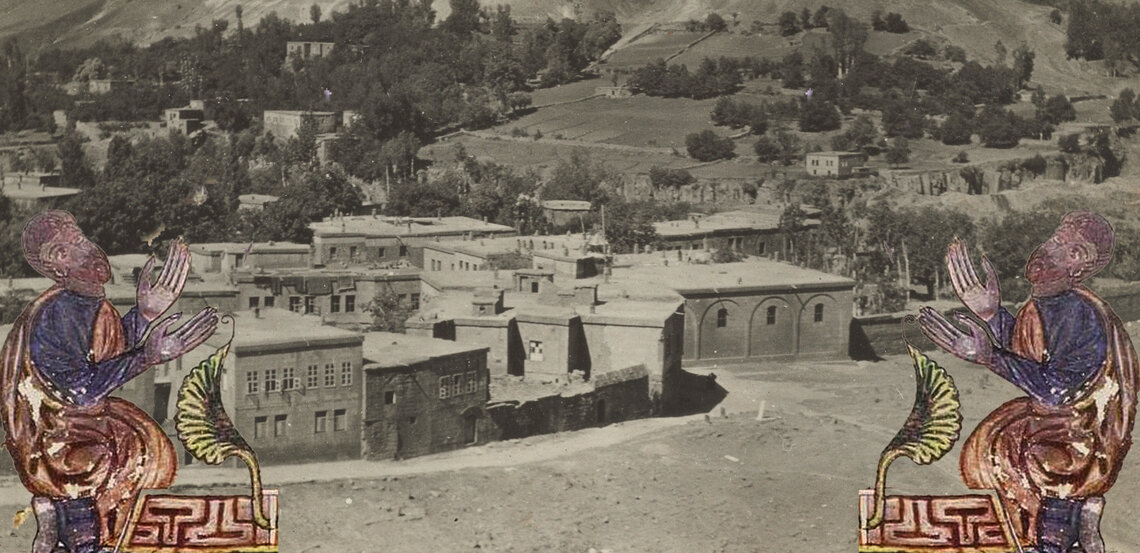

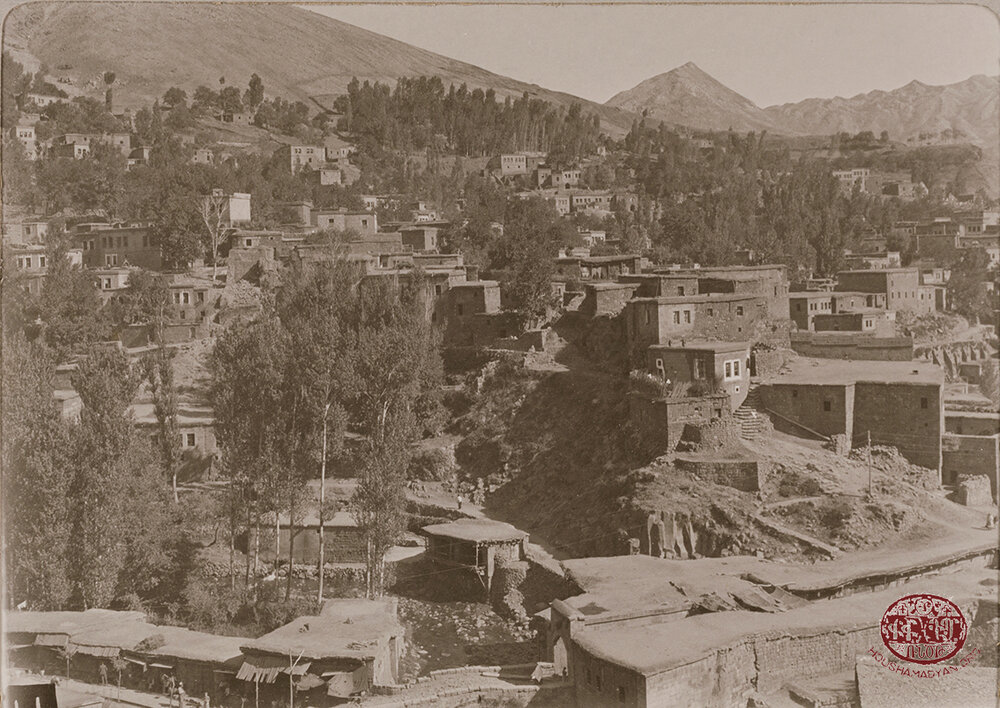

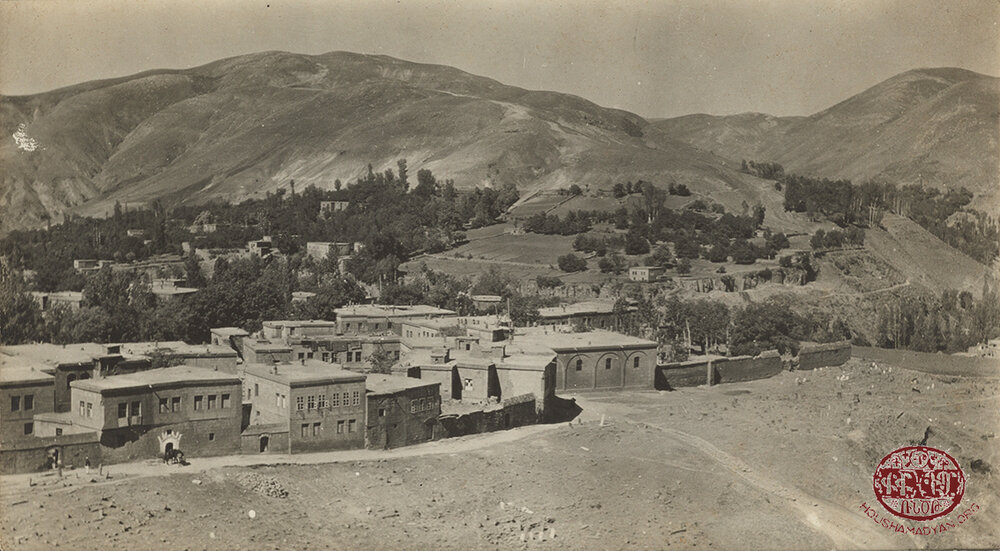

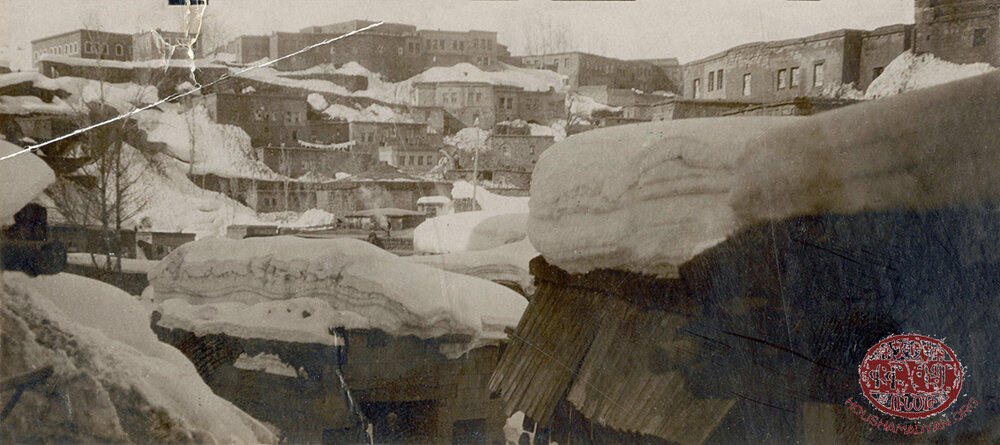

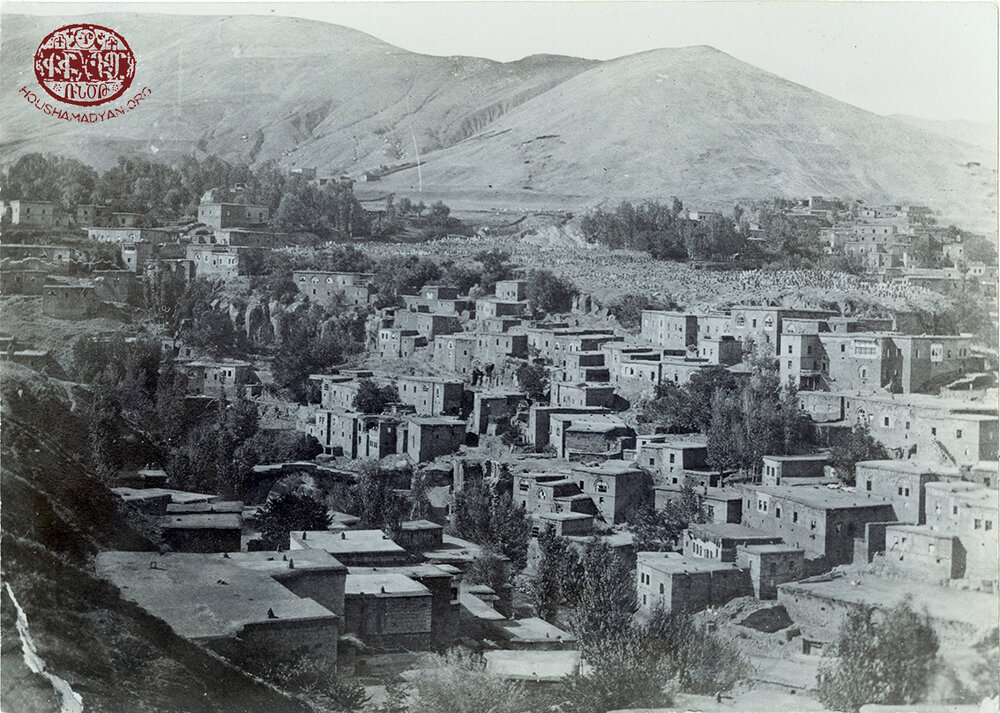

Paghesh or Bitlis was the largest city, as well as the administrative seat, of the province of Bitlis of Western (Ottoman) Armenia. The city was also the administrative seat of the eponymous district and subdistrict. Historically, Bitlis was part of Salnotsor District of Aghtsnik Province of Greater Hayk. The territory of the Ottoman subdistrict also stretched into the historical district of Bznounik/Pznounik of Tourouberan (Taron)/Dourouperan (Taron) Province of Greater Hayk. [1]

In the early Middle Ages, Paghesh was one of the prominent fortresses of southern Armenia. It played an important role within the defensive system of the strategically and economically vital highway that led to Middle Armenia via the Tsorahabag or Paghisha (Rahva) mountain pass in the Taurus Mountains. [2] The eponymous city gradually grew and thrived around this fortress over the years. The first mention of Paghesh in Armenian historiography is by Sebeos in the seventh century [3]. By the ninth century, Tovma Artsruni was already describing the city as a shahasdan, or a wealthy trading hub. [4]

Paghesh was occupied by foreign powers early in its history. It was conquered by the Arabs in the second half of the seventh century; the Byzantines for a short time in the tenth century; the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century (it was under their rule that the city became widely known as Bitlis); and by the Turkish Qara Qoyonlu clan in the 15th century. [5] In 1514, the Ottoman Empire established its rule over Bitlis, which was initially a district within Diyarbakir Province, and later (1568-1738) within Van Province. [6]

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Ottoman rule over Bitlis was, in many ways, only nominal. The area was under the de facto rule of the Ruzakid or Roshka Kurdish tribe. The city was the seat of the tribe’s leaders. Kurdish authority over Bitlis was consolidated between the 17th and 19th centuries, leading to the Ottoman Sultan officially recognizing the area as a Kurdish hukumet. [7] It wasn’t until 1849 that the central Ottoman authorities were finally able to crush resistance by Kurdish chieftains and fully establish their rule over the area. [8]

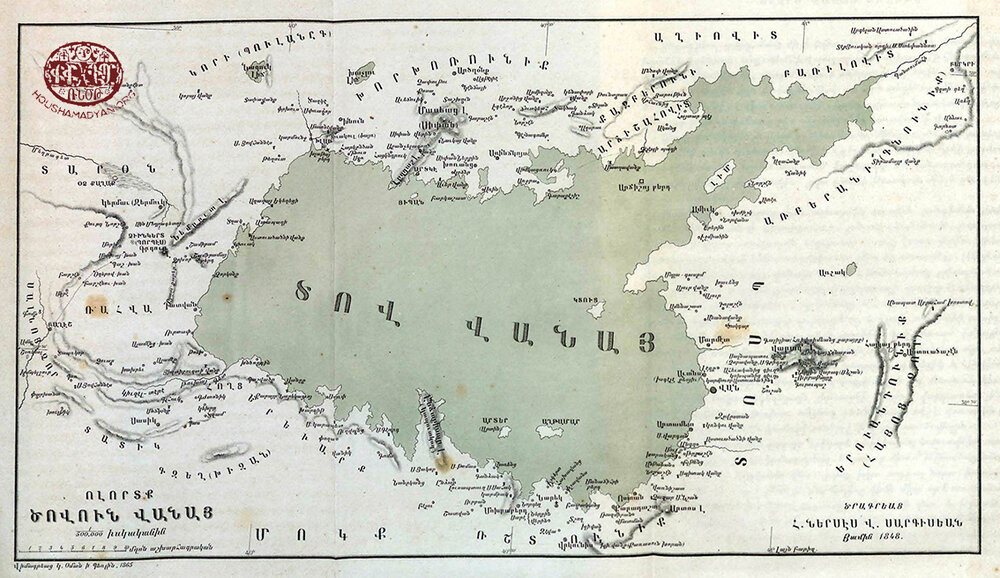

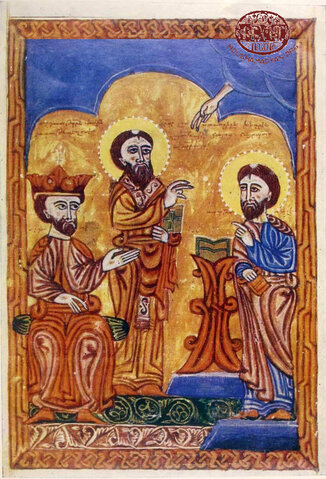

The Paghesh Diocese was the successor of the ancient bishopric whose seat was Khlat (approximately 60 kilometers northeast of Paghesh, on the shores of Lake Van). The Khlat Bishopric is mentioned in records from the fifth century. In addition to Paghesh, it had jurisdiction over Ardzgen [9], Khizan [10], and Tadvan. [11]

The seat of the bishopric was relocated from Khlat to Paghesh between 1437 and 1440. [12] The growth of the diocese in the 16th and 17th centuries is evidenced by the fact that the order of the Saint Arakelots Monastery of Moush joined the Bitlis Diocese. [13] Notably, records from the 1770s indicate that the Paghesh Bishopric, alongside the Saint Garabed Monastery of Moush, was subject to the authority of the Echmiadzin Catholicosate. [14]

From 1860 to 1872, the dioceses of Paghesh and Moush operated as a united diocese, under the leadership of Father Yeremia Devgants. [15] Beginning in 1868, this same united diocese also had jurisdiction over Keghi. [16]

From 1872 to 1915, the diocese of Paghesh operated as a discrete bishopric. Its jurisdiction included the Bitlis and Khlat subdistricts of the district and province of Bitlis, as well as either all or some of the villages of the Modgan region in the Modgan subdistrict. [17]

In 1882-1883, Karekin Srvantsdyants served as the interim prelate of the diocese. Concurrently, he served as the prelate of the Agn Diocese. [18]

Between 1884 and 1886, Father Mesrob Mogatsian served as the interim prelate of the diocese. In 1886, he was succeeded by Father Movses Geomukdjian. [19]

Between 1895 and 1897, Father Hagopos Shahbaghlian served as the interim prelate of the diocese. [20]

Between 1897 and 1900, Father Yeghishe Chilingirian served as the interim prelate of the diocese, after which, in 1900-1901, he served as its appointed prelate. [21] In 1901-1902, Father Bedros Shahinian served as the interim prelate of the diocese. [22]

Between 1902 and 1907, Senior Priest Father Yeznig Kalpakdjian served as the appointed prelate of the diocese, with Father Bedros Shahinian and Father Parsegh Sarkisian serving as coadjutors. [23]

Between 1908 and 1910, Father Yeznig Nergararian served as the interim prelate of the diocese. [24]

On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, the serving prelate of the diocese was Senior Priest Father Souren Kalemian. [25] On June 22, 1915, by order of the Ottoman authorities, he and the Very Reverend Khachadour Vartanian, the leader of the Protestant Armenian community of the city, were killed, [26] an event followed by the wholesale massacre and deportation of the city’s and district’s Armenian population. The Paghesh Diocese ceased to exist.

According to Maghakia Ormanian, in the early 1900s, the Paghesh Diocese included 80 Armenian-populated settlements, with a total population of 50,000 Apostolic Armenians, 500 Catholic Armenians, and 1,000 Protestant Armenians. [27]

The 1913 census conducted by the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate provides much more detailed figures. According to the census, the city of Paghesh was home to 1,135 Armenian households, with a population of 7,241 Armenians. The census also lists 95 Armenian-populated villages across the Paghesh Diocese, home to 4,403 Armenian households and a population of 33,902 Armenians. Of these, 46 Armenian-populated settlements were located in the Paghesh subdistrict (2,120 households, 14,573 individuals); 22 settlements in the Khlat subdistrict (1,771 households, 13,860 individuals); and 27 settlements in the villages of the Modgan subdistrict that were included in the territory of the Paghesh Diocese (512 households, 5,469 individuals). Based on these numbers, the total Armenian population of the Paghesh Diocese in 1913 was 5,538 households and 41,143 individuals. [28]

In the early 1900s, there were a total of 11 standing monasteries and approximately 100 functioning churches across the Paghesh Diocese [29] (according to Ormanian, the exact number of churches was 98 [30]).

According to the 1913 census, there were a total of 12 standing monasteries and 72 churches across the subdistricts of Paghesh and Khlat [31]; and four standing monasteries and 26 churches in the subdistrict of Modgan. [32] According to these figures, on the eve of the Genocide, there were 16 standing monasteries and 98 functioning churches across the Paghesh Diocese.

The Armenian Protestant Community of Paghesh

The Protestant mission of Paghesh was one of the largest and most developed centers of the Protestant church in Western Armenia.

The mission was established in 1858 by American missionary George Cushing Knapp [33], who continued working in Bitlis until his death in 1895. [34] Aside from him and his wife, Alsina Knapp, the mission’s staff initially included a local Armenian preacher and a local Armenian custodian. [35]

According to information from 1867, the mission, in addition to the local Armenian preacher, also employed two teachers. Attendance at the meeting hall registered an average of 74 worshippers. The mission operated a Saturday school, which had an enrollment of 67 pupils. Protestant sub-missions were opened in four other settlements across the district of Bitlis, with a staff that included one local, accredited preacher; one teacher; and three assistants. These sub-missions served 87 parishioners and operated two Saturday schools, with an enrollment of 45 pupils. [36]

In 1868, Lysander Burbank and his wife, Sarah, joined the Bitlis mission (they stayed in Bitlis until 1871). Additionally, the mission hosted the sisters Charlotte and Mary Ely, who opened the Mount Holyoke girls’ boarding school in the city (for more information on this institution, see Houshamadyan’s “Bitlis – Missionaries” article.

Between 1876 and 1881, the Bitlis and Moush districts were absorbed into the province of Van. As a result, the Protestant mission of Bitlis began operating as a chapter of the Van mission, functioning as such until 1886. [37]

In the late 1880s, Protestant communities existed in 15 Armenian-populated villages across the Bitlis District. [38]

In 1890, George Cushing Knapp’s son, George Perkins Knapp (Knapp Jr.) joined the Bitlis mission. [39] Due to his father’s deteriorating health, Knapp Jr. acted as the de facto leader of the local Protestant mission starting in the mid-1890s, alongside missionary Royal M. Cole. [40]

When the wave of violence unleashed by the Hamidian massacres reached Bitlis in the second half of 1895, Knapp Jr. saved numerous lives by sheltering Armenians in Protestant institutions. [41] He also prepared a report on the massacres, which he sent to the U.S. ambassador in Constantinople and the diplomatic representatives of European powers. [42] As a response to his pro-Armenian activities, the Ottoman authorities decided to expel Knapp Jr. from Bitlis in 1896, accusing him of encouraging anti-government sentiments among the locals. [43]

After Knapp Jr.’s expulsion, the Armenians of Bitlis and Moush composed a song in his honor, which included the following lyrics:

Convey our greetings to George the American,

We will not forget his good deeds,

May God grant him long years. [44]

After the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, Knapp Jr. was allowed to return to Bitlis and continue his work. During the Armenian Genocide, he once again tried to shelter Armenians in the buildings of the Protestant mission. However, on June 23, 1915, the Ottoman police raided the mission and arrested the Armenians hiding there. [45] In July 1915, the Ottoman authorities exiled Knapp Jr. to Diyarbakir, where he died immediately upon arrival. [46]

Detailed information on the activities of the Protestant mission in Bitlis in the mid-1890s is provided by Henry Lynch, a British traveler. According to him, the Protestant mission was located in the Avermeydan (Avel Meidan) neighborhood. The missionaries’ work was focused less on proselytization and more on the expansion of the local network of Protestant schools. The city was home to a Protestant senior school, and other Protestant schools operated in 15 Armenian-populated settlements across the district. Lynch described the then-leaders of the mission, Knapp Sr., Knapp Jr., and Royal Cole as zealous, experienced, and amiable men. He noted that the same neighborhood was home to a newly constructed Protestant church, which was partly funded by the local Protestant community. According to him, the number of Protestant Armenians in the city was 100, and the total Armenian Protestant population of the district was 1,200. Armenians who had converted to Protestantism showed no desire to abandon their national character; on the contrary, they clung fast to their Armenian identity. [47]

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution led to a period of growth for the Armenian Protestant community in Bitlis, thanks to the easing of the persecution that Armenians had experienced under the Hamidian regime and the relative liberalization of sociopolitical life across the Empire. According to the 1910 Protestant Board report, the staff of the Bitlis mission included one family (presumably, the family of Knapp Jr.); two women missionaries (the Ely sisters); one native ordained pastor ; seven other preachers; ten male teachers; six female teachers; four women who conducted Bible readings (“Bible women”); and one worker tasked with overseeing relief operations (“relief agent”). In Bitlis, the Protestant community owned and operated one church, two boarding schools and high schools, eight village meetings halls (“chapels”) with attached schools, an orphanage, and a sewing workshop (“cloth factory”). Significant amounts of aid were distributed to local Armenians. Efforts were being made to revive Protestant communities in villages where they had previously existed, as well as to establish new Protestant communities. [48]

On the eve of the Armenian Genocide, the leader of the Armenian Protestant community of Paghesh was the VeryReverend Khachadour Vartanian. As we have already mentioned, he was killed alongside the prelate of the Apostolic diocese of Paghesh, Senior Priest Father Souren Kalemian, on June 22, 1915. [49]

In the early 1880s, Armenian Protestant communities existed in the settlements of Gdzvag, Dzghag, Aghagh (entirely Protestant), Dzersonk (entirely Protestant), and Prkhous of the Khlat subdistrict. [50]

According to the 1913 census conducted by the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate, a total of 258 Armenian Protestants lived in the city of Bitlis. [51] According to official government statistics from 1914, a total of 384 Armenian Protestants lived in the subdistrict of Bitlis, and 207 in the subdistrict of Akhlat. [52]

The Armenian Catholic Community of Paghesh

Maghakia Ormanian wrote that 500 Armenian Catholics lived across the Bitlis Diocese in the early 1900s, [53] but the actual number of Catholic Armenians was evidently significantly smaller. British traveler Henry Lynch, who journeyed across Armenia in the mid-1890s, wrote that there were only 15 Armenian Catholic families in the city, of whom only three or four had been converted recently by the Jesuits who had been active in the region. [54] The city’s Catholic community was served by Armenian clergymen who had graduated from the Jesuits’ College of Beirut. This college had also founded a school in the city for the children of local Catholic families. [55]

According to the 1913 census conducted by the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate, there were only 20 Catholic Armenians in Bitlis. [56] According to official government statistics from 1914, the total number of Catholic Armenians living in the subdistrict of Bitlis was 89. [57]

- [1] Tatevos Hagopian, Badmagan Hayasdani Kaghakneru [Cities of Historic Armenia], Yerevan, 1987, pp. 99-100.

- [2] Kegham M. Patalian, “The Historical and Demographic Character of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide. Part Eight: The Historical Province of Sassoun and the City of Paghesh (Bitlis),” VEM Pan-Armenian Review, 2017, number 2 (58), Supplement, p. XLI.

- [3] T. Kh. Hagopian, Sd. D. Melik-Pakhshian, and H. Kh. Parsehgian, Hayasadni yev Haragits Shrchanneri Deghanounneri Pararan [Dictionary of Place of Names of Armenia and the Environs], volume 1 (A-D), Yerevan, 1986, p. 685.

- [4] “Paghesh,” Haygagan Sovedagan Hanrakidaran [Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia], volume 2, Arkishdi-Keghervan, Yerevan, 1976, p. 255.

- [5] Hagopian, Badmagan Hayasdani Kaghakneru, p. 100.

- [6] Andreas Birken, Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches, Wiesbaden, Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 1976, p. 186; Sezen Tahir, Osmanli Yer Adlari, Ankara, 2017, p. 124.

- [7] The Kurdish princes that ruled over Paghesh were called khans, and their subordinate chieftains were called beys (see Mgo, “The District of Paghesh,” Artsakank Literary and Political Periodical, Tbilisi, 17 October 1882, n. 35, p. 541).

- [8] “Paghesh,” Haygagan Sovedagan Hanrakidaran, volume 2, p. 254.

- [9] Ardzge (Atilchevaz), an ancient city in the Pznounik District of Darouperan Province of Greater Hayk, east of Khlat, on the northern shore of Lake Van.

- [10] Khizan or Hizan, a city in the Mus Ishayr District of the Mogk Province of Greater Hayk, located approximately 50 kilometers southeast of Paghesh.

- [11] Arshag Alboyadjian, “Jurisdictions of Dioceses,” 1908 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1908 Expanded Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1908, p. 313.

- [12] Ibid.

- [13] Ibid., p. 314.

- [14] Byon Hagopian, Hayakidagan Osoumnasiroutyunner [Inquiries in Armenian Studies], Yerevan, 2003, pp. 103, 105, and 208.

- [15] Archbishop Maghakia Ormanian, Azkabadoum [National History], volume C, Jerusalem, 1927, p. 4173 (Section 2776). Yeremia Devgants left behind a rich literary heritage (diaries, travel journals, journals, etc.), some of which has been published (see Y. Devgants, Djanabarhortoutyun Partsr Hayk yev Vasbouragan, 1872-1873 [Travels in Upper Hayk and Vasbouragan, 1872-1873], edited and compiled by H. M. Boghosian, Yerevan, 1991, 343 pages; and Yeremia Devgants, Dohmayin Hishadagaran. Kirk VIII (1868-1872) [Family Chronicle, Book VIII (1868-1872), compiled by H. Gh. Mouratian, Yerevan, 2018, XIX + 440 pages.

- [16] Arshag Alboyadjian, “Jurisdictions of Dioceses,” p. 314.

- [17] Alboyadjian, “Jurisdictions of Dioceses,” p. 314; and Archbishop Maghakia Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin yev ir Badmoutyunu, Vartabedoutyunu, Varchoutyunu, Paregarkoutyunu, Araroghoutyunu, Kraganoutyunu, ou Nerga Gatsoutyunu [The Armenian Church and its History, Priesthood, Administration, Reforms, Rituals, Literature, and Present State], Constantinople, 1911, p. 262. For a list of settlements in Modgan that were part of the Paghesh Diocese, see Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev Ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Darin [The Calvary of the Armenian Clergy and Its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915], Second Edition, Tehran, 2014, p. 127. According to one source, 14 Armenian-populated settlements in the Kzekh village cluster in Modgan were within the territory of the diocese of the Saint Aghperig Monastery of Sassoun, and were consequently considered to be under the jurisdiction of the Moush-Daron Archbishopric (see “A Forsaken Subdistrict (Modgan),” Azadamard Newspaper, Constantinople, 21 February (6 March), 1914, number 1445).

- [18] Emma Gosdantian, Karekin Srvantsdyants (Gyanku yev Kordzouneyoutyunu) [Karekin Srvantsdyants (His Life and Works)], Yerevan, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia, Institute of History, 2008, p. 28.

- [19] “News from Paghesh,” Armenia National, Political, Commercial, etc. Periodical, Marseille, 20 February 20 1866, number 54, p. 3.

- [20] “Correspondence to the Hairenik,” Hairenik National, Literary, and Political Daily, Constantinople, 12 October 1895, number 1309, p. 1 (the newspaper reports that prior to the appointment of Shahbaghlian to this position, the Paghesh Diocese was without a leader “for several years, as a result of which the affairs of the prelacy were in disarray”). Also see Ararad Monthly, Vagharshabad, April 1895, p. 140.

- [21] 1900 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1900 Expanded Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1900, p. 407. Father Yeghishe Chilingirian (later a bishop) also wrote memoirs that contain descriptions of many of the events that occurred during his term as prelate (see Bishop Yeghishe Chilingirian, Hishadagner Saghimagan, Oughekragan, Deghakragan, yev Namagani, Alexandria, 1920, p. 118).

- [22] 1902 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1902 Expanded Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1901, p. 528.

- [23] 1903 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1903 Expanded Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1902, p. 335. Also, figures from subsequent editions of the expanded calendar.

- [24] 1909 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1909 Expanded Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1908, p. 323; 1910 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots [1910 Expanded Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople, 1909, p. 538.

- [25] Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan…, Second Edition, Tehran, 2014, p. 88.

- [26] Ibid.

- [27] Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin…, p. 262.

- [28] These numbers were calculated by us, based on the statistics presented for each village in the census (AGBU Noubarian Repository Archive, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff. 49-52; 60). Also see Robert Tatoyan, The Armenian Population of the Province of Bitlis of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide, Lebanon, Chirak Printing and Publishing, 2022, pp. 83-97.

- [29] 1903 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots, p. 337; 1904 Untartsag Oratsouyts S. Prgchian Hivantanotsi Hayots, p. 374.

- [30] Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin…, p. 262.

- [31] These numbers were calculated by us, based on the list of villages (AGBU Noubarian Repository Archive, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff. 49-52).

- [32] These numbers were calculated by Raymond-Haroutyun Kévorkian, based on statistics from AGBU Noubarian Repository Archive, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, ff. 60 (Raymond H. Kévorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Arménians dans l’Empire Ottoman à la Veille du Génocide [The Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the Genocide], Paris, ARHIS, 1992, pp. 59, 477).

- [33] Historical Sketch of the Missions of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, in European Turkey, Asia Minor, and Armenia, New York, 1866, p. 40.

- [34] See his obituary in the 1895 yearbook of the American Missionary Herald (Missionary Herald: Containing the Proceedings of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions with a View of Other Benevolent Operations, for the Year 1895, vol. XCI, Boston, 1895, pp. 187-188).

- [35] Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at Boston, Mass. October 2-5, 1860, Boston, 1860, p. 78. For details on the challenges faced by the mission in the first years of its existence, see ibid., pp. 80-81.

- [36] Annual Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at Buffalo, New York. September 23-27, 1867, Cambridge, 1867, pp. 75 and 77.

- [37] For detailed information on the activities of the mission during these years, see Annual Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at St. Louis, MO. October 8-21, 1881, Boston, 1881, p. 51; Annual Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at Portland, Maine. October 3-6, 1882, Boston, 1882, pp. 40, 44; Annual Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at Detroit, Michigan. October 2-5, 1883, Boston, 1883, p. 53; Annual Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at Columbus, Ohio. October 7-10, 1884, Boston, 1884, pp. 39-40; Annual Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at Boston, Mass. October 13-16, 1885, Boston, 1885, pp. 47-48.

- [38] Annual Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at Cleveland, Ohio. October 2-5, 1888, Boston, 1888, p. 41.

- [39] Annual Report on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Presented at the Meeting Held at Minneapolis, Minnesota. October 8-11, 1890, Boston, 1890, p. 47. George Perkins Knapp was born in Bitlis in 1863. At a young age, he was sent to the United States to receive his education. Upon graduation from school, he was accepted into the Hartford Theological Seminary. After graduating from this institution, he returned to Tbilisi (see Sdepan Payaslian, “American Missionary George Knapp’s Report on the Massacres of the Armenian Population of Bitlis,” Panper Hayasdani Arkhivneri [Register of the Archives of Armenia], 2004, n. 2 (104), p. 17).

- [40] Garo Sassouni, Badmoutyun Darono Ashkharhi [History of the Land of Daron], Antilias, 2013 (republished), p. 288.

- [41] Ibid.

- [42] For an Armenian translation of the report, see Payaslian, “American Missionary George Perkins Knapp’s Report on the Massacres of the Armenian Population of Bitlis,” pp. 17-29.

- [43] Payaslian, “American Missionary George Perkins Knapp’s Report on the Massacres of the Armenian Population of Bitlis,” p. 17. Also see Sassouni, Badmoutyun Darono Ashkharhi, p. 289.

- [44] Sassouni, Badmoutyun Darono Ashkharhi, p. 289.

- [45] Grace H. Knapp, The Tragedy of Bitlis, New York, 1919, pp. 50-51.

- [46] The official cause of Knapp Jr.’s death was typhus, but rumors circulated that he was poisoned (Knapp, The Tragedy of Bitlis, p. 126). Leslie Davis, the American consul in Kharpert, also expressed his doubts regarding the American missionary’s cause of death: “It is highly doubtful that the cause of his death was typhus. However, apparently, there is no possible way to ever discover the truth … Most probably, we will never know whether Mr. Knapp died of typhus or as the result of poisoning” (United States Official Documents on the Armenian Genocide, Volume III: The Central Lands, compiled and introduced by Ara Sarafian, Watertown, Massachusetts, 1995, pp. 78-79).

- [47] H. F. B. Lynch, Armenia. Travels and Studies, volume 2, The Turkish Provinces, London, 1901, pp. 153-154.

- [48] Survey of the Work of the American Board in Turkey. Reprinted out of the “Orient” of July 6, 1910, Bible House, Constantnople, Turkey, p. 11.

- [49] Teotig, Koghkota Hayots Hokevoraganoutyan…, p. 88 and 90; Sassouni, Badmoutyun Daroni Ashkharhi, p. 289.

- [50] M. Mirakhorian, Ngarakragan Oughevoroutyun i Hayapnag Kavars Arevelyan Dadjgasdani: Deghakroutyunk Saren yev Tsoren, Hnen yev Noren Bidani Kidnots [Accounts of Travels across the Armenian-Populated Provinces of Eastern Turkey: Topography of the Mountains and Valleys, Useful Information on the Old and the New], Part A, Constantinople, 1884, pp. 85-88.

- [51] AGBU Noubarian Repository Archive, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 49.

- [52] Kemal H. Karpat, Ottoman Population 1830-1914. Demographic and Social Characteristics, Wisconsin, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985, p. 174.

- [53] Ormanian, Hayots Yegeghetsin…, p. 262.

- [54] H. F. B. Lynch, Armenia. Travels and Studies, p. 153. The British traveler, citing other sources, stated that the number of Catholic Armenian families in Bitlis was once as high as 30, but that by the early 1880s, due to persecution and internecine conflict, only nine such families were left in the city.

- [55] Ibid.

- [56] AGBU Noubarian Repository Archive, APC/BNu, DOR 3/3, f. 49.

- [57] Karpat, Ottoman Population 1830-1914…, p. 174.