Palu - Geography

How to reach Palu

How does one get to this district located in a spot in the centre of the Armenian Highlands from Istanbul? There are three main routes. The first is the Mediterranean route to the port of Mersin then, joining a caravan, taking the route to Palu, stopping at Adana and Marash. This journey might take 15 days and is called the winter route. The second takes us through the Black Sea to the port of Samsun, then by caravan to Amasia, Tokat, Sivas, Harput and finally Palu. This can take 16 days and is known as the summer route. The third is also via the Black Sea and takes us to Trabzon then, joining a caravan, to Gumushkhane, Erzindjan then, passing near Kghi, to Palu. This may be considered to be the shortest route as it only takes 10 days. Compared to the other routes however, this is more difficult, bearing in mind its mountainous nature. For this reason it is known as the summer route.

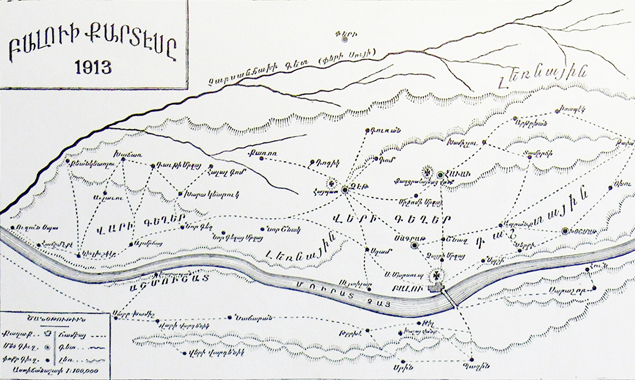

The description of these routes was written by the archpriest Rev Boghos Natanian, who was the diocesan leader of Palu in 1878-1879 [1]. Several decades later the route from the north of the town of Palu via Harput to Erzurum begins. This route cuts through the Palu plain from east to west and passes the villages of Nbshi (Nipşi), Norshnag (Beşpınar), Nor Kiugh Mezre (Yeniköymezreası), Nor Kiugh (Yeniköy), Armoudjan (Yarımca) and Giuliushger (Muratbağı). No major road, however, links Palu to this highway [2].

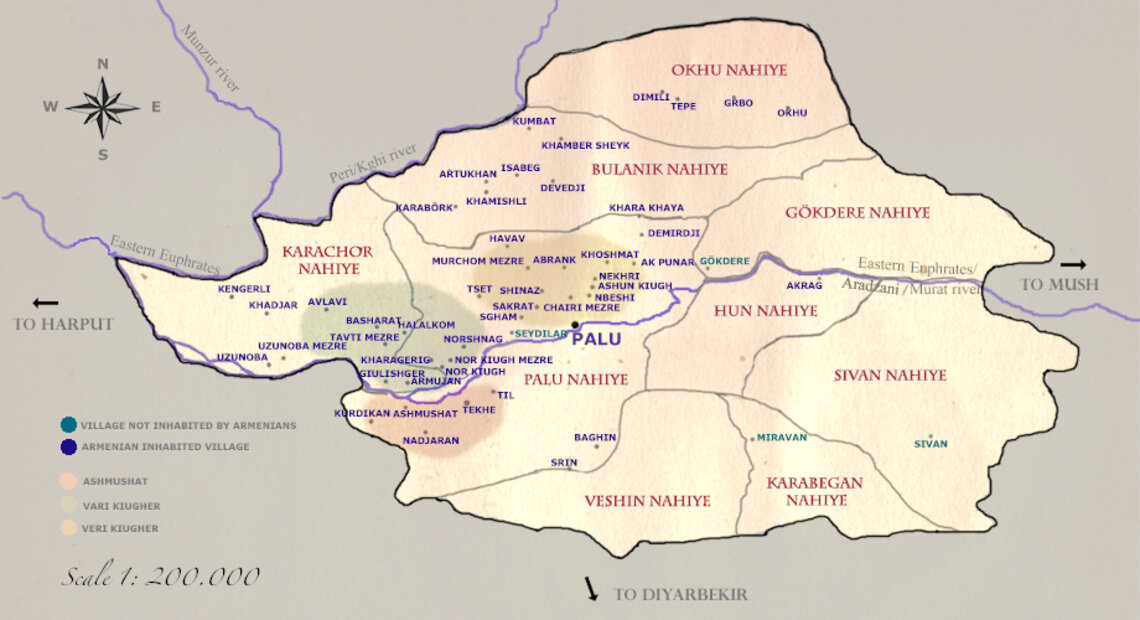

To make Palu’s location on a map clear, we should say that the most important city from the east that is nearest is Mush; from the west it is Harput; from the south Diyarbekir; and from the north Kghi and Erzindjan. The Aradzani River (Murad Chai or Eastern Euphrates) divides the Palu district into two: to the south, or on the left bank of the river, are the Armenian-inhabited villages of Til (Gömeçbağlar), Trkhe (Keklikdere), Nadjaran (Baltaşı) and Kurdikan (Gümüşkaynak). These last are called Armushad, or Southern Villages. The town of Palu is located in the northern part and, in the area stretching towards the west are to be found the Turkish-inhabited village of Seydiler, as well as the Armenian villages of Nor Kiugh (Yeniköy), Nor Kiugh Mezre (Yeniköymezreası), Armudjan (Yarımca), Giuliushger (Muratbağı), Tavti Mezre (Tavtik) and Uzunoba. All the above-mentioned villages are on the right bank of the Aradzani River and are known as the Lower Villages (Vari Kiugher). The well-watered and fertile fields that are part of the district are to be found in the plain stretching from west to east that is north of the town. This area is known as the Upper Villages (Veri Kiugher). This is the most densely Armenian-populated part of the district and there are relatively few Kurdish villages there. The Armenian-inhabited villages of Tset (Kapıaçmaz), Sgham (Pınartepe), Sakrat (Yazıbaşı), Shinaz (Saraybahçe), Abrank (Köprüdere), Murchomi Mezre (Karıncaköy), Chairi Mezre (Chayri Mezre), Havav (Ekinözu), Nerkhi (Nirhi), Nbeshi (Nipşi), Khoshmat (Çakurkaş), Khamishli (Kamişli), Artukhan (Soğukpınar), Isabeg (Isabeg) and Kumbat (Kümbet) are to be found here. The two Armenian-inhabited villages of Okhu (Bulgurcuk) and Tepe (Karakoçan) are to be found further to the north-east and are rich with their fields. Small Armenian villages exist in the foothills of the mountains that surround this area. It should be said that in these mountainous regions, whose height is up to 2500 metres, the Armenians are a small minority and the absolute majority of the inhabitants are Kurds [3].

It becomes clear from this description that the Armenian population of the Palu district is mostly centred on the immediate left bank of the Aradzani River and especially in the plain on the right side of the river. This area constitutes the district’s western part. The Kurds are the overwhelming majority of the population in the remaining areas – north, south and east.

The town of Palu: its location and description

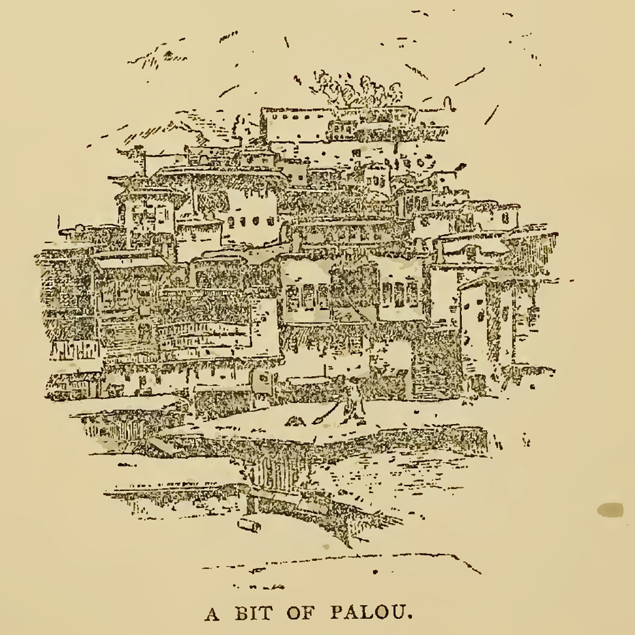

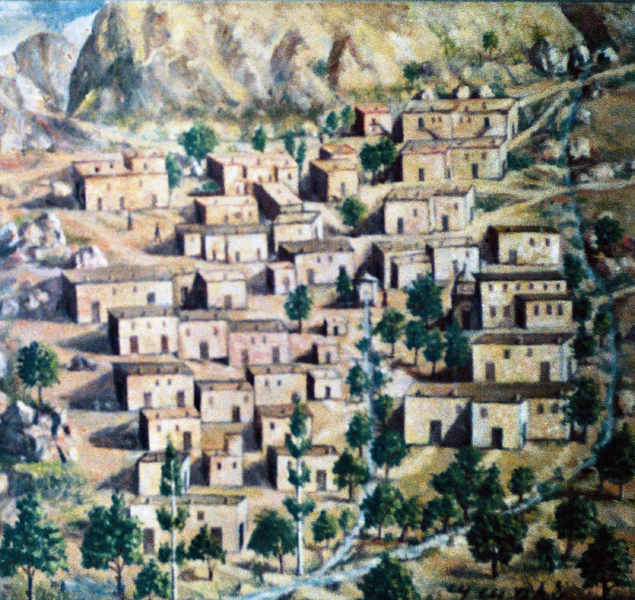

The town is built on the southern bank of the Eastern Euphrates, in a valley at the foot of Mount St. Mesrob. On the summit of that same mountain are the ruins of a fort from the Urartuan period. The town is characterised by its irregular streets and constant undulations, making movement difficult. Palu is surrounded on its northern and southern sides by high mountains which determine the climate, especially the summer, when the weather is not healthy.

There are four Armenian quarters in the town: Yerevan, Doner, St Sahag and St Giragos. The last two, at the end of the 19th century, were in ruins and deserted, therefore Armenian life is centred in the Yerevan and Doner quarters [4]. These were built at the foot of St Mesrob Mountain, on the side facing the Aradzani River. The people of Palu call this descending slope Keran. According to the facts available in the 1870s, there were 585 households of Armenians living there forming a population of 4683 people. The two working churches in the town are St Gregory the Illuminator and The Holy Mother of God although, according to the 1870s information, both St Sahag and St Giragos churches were still being used. It was a few decades later that, when the quarter’s Armenian population left, those two churches would be abandoned by their congregations. The St Toros pilgrimage site is located on the brow of the mountain, a little above the Armenian quarter [5]. The Armenian Protestants also have a prayer hall in Palu. On the south side, the summit is called Kohanamk by the Armenians and is a place of pilgrimage for the local population. Another pilgrimage place is on the northern side of the mountain, the former St Boghos monastery, of which only ruins remain [6].

The government centre was formerly located in a place about a quarter of an hour from the town, but it has been demolished and a new building was erected exactly in the centre of the town [7].

The town of Palu is not well watered. It’s true that the Aradzani flows by it, but it’s not easy to get water to the various part of the town, which is quite high up. It is probably for the same reason that the town and its immediate surroundings are generally devoid of green spaces. There are only a few poplar and almond trees in the whole town. This lack of water is somewhat alleviated by the existence of three fountains called Shar, Var and Djemi that are much used by the inhabitants of the Armenian quarters. There is also the icy water of the bath-house, the source for which is located in the lower Turkish quarter. During the summer, those in the Armenian quarters with horses or nags would come there and, having filled containers with cold water, would load them on to their animals and bring it up into the Armenian quarters [8].

The Turkish quarters are separate from those of the Armenians. The Turks live in three different areas. The first is Zovia, located in the town’s north-western area behind the fort, and is a large quarter with about 242 households and two mosques. The other Turkish quarter, Ashaghki Mehle, is located south-east of the fort just behind a fortress-like massif on the river bank called Kntiga Rock. This quarter consists of 436 households. The third, Charshe Bashi, is in the middle of the town above the market and settled on a slope. This quarter has 528 households. There are a total of 1206 Turkish-occupied households or 7236 Turkish inhabitants living in Palu itself, according to the figures produced in the 1870s [9].

Just before the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78, and based on Salname facts – that in this instance only quotes the number of males – the number of Armenians in the district was assessed at 20% of the population and in Palu itself at 40%. Immediately after the war, when Palu had been joined to the province of Mamuret-el-Aziz, the percentage of Armenians in the district was thought to be 40%, due to the extraordinary fall in the number of Muslim males. At the beginning of 1890, in the Sultan Abdul Hamid era just before the anti-Armenian massacres, the number of Armenians in the district was considered to be between 13,000 and 14,000 individuals, in other words 25% of the total population. The 1895-96 massacres were the reason for the noticeable decline in their numbers. Just before the outbreak of the First World War, however, the number of Armenians in the district was assessed as 15,000 [10].

There are practically no shops in the villages in the Palu district, although the exception is the Armenian village of Havav (Ekinözu). Thus the town’s market is the place that the townspeople and the people from the villages can trade. There are old and new khans (overnight resting households) there. Mercantile houses ply their trade and tradesmen have their own shops too. The market area is generally full of villagers who arrange the produce they’ve brought with them and sell it. Among the things they sell are wheat, barley, wood and fuel [11]. To the west of the town, on the road to Sgham (Pınartepe), is an Ottoman barracks. Anyone coming to the town from the south has to go over a bridge over the Aradzani River. It has stone-built piers, on which a wooden roadway has been built that, according to contemporary accounts, is quite decrepit. Right next to the bridge, on the same west bank, is a government guard post, supervising all the travellers and their goods that pass by [12].

The administrative state in the Ottoman Empire

For a long time Palu has been part of the eyalet of Diyarbekir. This changes in the 19th century when, under the glare of the reforms of the tanzimat, the whole of the administrative system of the Ottoman Empire is reviewed and the country’s internal administrative divisions are redrawn. Thus in accordance with the provisions of the salname, Palu is joined administratively with Harput (Mamuret-el-Aziz) a newly-formed county (liva) created from the two sandjaks of Harput (Mamuret-el-Aziz) and Arghana Maden. At that time Palu was organised as a kaza and consisted of the following müdürlüks (sub-district): Palu, Karabegan, Djabaghchur (Bingöl) and Egil. They in their turn were divided into nahiyes or nevahis as follows.

- Palu

Palu (79 villages),

Bulanik (49 villages),

Hun (9 villages),

Karachor (38 villages),

Ohi (20 villages)

Karabegan

Karabegan (15 villages),

Vishin (14 villages),

Gök Dere (25 villages),

Sivan (11 villages)

Djabaghchur

Djabaghchur (55 villages),

Meneshkut (-)

Egil

Egil (70 villages),

Nerib (10 villages),

Terkan (-)

The same salname, a year later, has the number of villages in the Sivan area corrected to show 41. Later, in the light of these administrative changes, the müdürlüks of Djabaghchur and Egili are separated, while the Palu kaza is attached to the sandjak of Arghana Maden, which in its turn is part of the Diyarbekir vilayet [13].

Apart from the Palu kaza, the Arghana Maden sandjak also includes the kazas of Arghana Maden and Chermug (Chermig). According to the information given in 1903, the Palu kaza is divided, in its turn, into nahiyes, as follows: Karabegan, Sivan, Gök Dere, Okhi, Bulanik, Karachor, Ashmishad (Achmichan), Hun (Khun) and Mazruat [14]. Rev Boghos Natanian quotes information available in the 1880s which shows only seven nahiyes, the last three in the above list being absent, with a new one, Voshi, being quoted [15]. Of these nahiyes, Mazruat includes the kaza’s central town, Palu, as well as 44 villages [16]. The nahiyes of Karachor, Voshi and Karabegan were mostly populated by Kurds. Bulanik, Gök Dere, Sivan and Okhu were mostly inhabited by Zaza Kurds [17].

According to information available in the 1870-1871 salname, there were 299 villages in the Palu area. Each named nahiye contained a number of villages: Palu 80, Bulanik 50, Hun 10, Karachor 39, Okhu 21, Gök Dere 26, Sivan 42, Karabegan 16 and Veshin 15. According to 1915 figures, this district had 323 villages [18].

Armenian-populated villages

Which of the villages in this area were Armenian-inhabited?

The Armenian-populated villages (most of the information concerning the population is based on the 1912 Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate’s census of 1912-1913)

AMARAT or ASHEN KIUGH (now Amarat): located to the north of Palu itself, and very near Nerkhi (Nirhi). The village contains some of the summer residences of Armenians from the town. There is a pool made of smooth stone in the centre of the square, with an area of about 10 sq. m (32 sq feet) and a depth of 1.5 m (5 feet). It also has a fountain supplying the pool with water [19].

ABRANK (now Köprüdere): about one and a half hours distant to the north of Palu itself [20]. It is located in a rural setting and contains about 23 households of Armenians and The Holy Mother of God church [21].

AVLAVI (now Avlaği): about 4 hours distance north-west of Palu itself. It is located in a valley and has a mixed population of Armenians and Kurds – 19 households of Armenians and 20 households of Kurds. They live in separate quarters [22].

ARTUKHAN (now Soğukpınar): to the north of the village of Khamishli (Kamişli), with 30-35 households of Armenians. It is located in a rural setting and has a church (St Minas) and a school with 45 pupils. The ruins of the church of St Thomas are located nearby [23].

ARMUDJAN (now Yarımca): located about four hours south-west of Palu itself. It had about 50 Armenian households in the 1870s and, just before the outbreak of the First World War, 30. It has a church (St Sarkis) and a school with 30 pupils [24].

AK PUNAR (now Akpınar): north-east of Palu itself.

TAVTI MEZRE (now Tavtik): about three hours distant from Palu itself, in a valley in the mountains. It had about 22 households of Armenians in the 1870s and, just before the First World War, 10. It has a church (St Giragos) and a school with 15 pupils [25].

TAPA or TEPE (now Karakoçan): north-east of Palu itself and west of Okhu (Bulgurcuk) village. It is in a rural setting. It was founded in the 1870s by about 48 households of Armenians, while at just before the First World War there were 61. There is a church (St Minas) and a school with 60 pupils [26].

TRKHE (now Keklikdere): south-west of Palu itself, about one hour distant from Nadjaran village, on the left bank of the Aradzani River. The village is high up, located at the base of a hill. It has a school with 16 pupils and a stone-built, cross-shaped church (St Sarkis). It is made up of 32 Armenians households. There is also one Zaza Kurdish and one Kurdish house there too [27].

TIL (now Gömeçbağlar): south-west of Palu itself, on the left bank of the Aradzani River. It is in a large valley and has a mixed population of Kurds and Armenians of 50 households, 24 of which are Armenian. The two groups live in separate quarters. There is a church (St Garabed) and a school with 14 pupils. The monastery of the Holy Cross is about 15 minutes distant from the village, and is also called Tila’s monastery (Tila vank) and is half in ruins. One of the region’s influential Kurds, Tefik Bey, has his house in the village [28].

ISABEG (now Isabey): about four hours distant north of Palu itself in a rural setting. It was formed in the 1870s by about 30 households of Armenians, and at the outbreak of the First World War contained 25. There is a church in the village (St Kevork) and a school with 45 pupils [29].

KHADJAR or KHADJAR MEZRE (now Kaçar): west of Palu itself and established at some height. It has 35 households of Armenians and 15 Kurdish ones. The village is known for its wine production. Rev Harutiun points out that the Armenians had left the village before 1915 [30].

KHAMISHLI (now Kamişli): north-west of Palu itself with nine Armenian households and a church (St Sarkis) [31].

KHARA KHAYA (now Kara Kaya): north-east of Palu itself with four households of Armenians and Zaza Kurds [32].

KHARAGERIG (now Kara Gelig): about 5 hours distant west of Palu itself and located at the foot of a mountain. It has a mixed Armenian and Kurdish population of 12 households that live in separate quarters. There is a church (Holy Cross) and a school with 11 pupils [33].

KHARABA (Arshamashad, Ashmishad) (now Harabe Köy): on the left bank of the Aradzani River. The ruins of an ancient fortress are located here that probably belong to the capital of Dzopk, Arshamashad [34].

KHARABÖRK (now Karabük): in a valley west of Khamashli (Kamişli) with 21 households of Armenians and about five of Zaza Kurds. It has a church (The Holy Mother of God) and a school with 30 pupils [35].

KHOSHMAT (now Çakurkaş): one hour north-east of Palu itself. The church of The Holy Mother of God was built here. It has extensive, fertile fields. 114 households of Armenians live here and there are two schools with 160 pupils [36].

GIULISHGER (now Muratbağı): over five hours west of Palu itself, on the bank of the Aradzani River and is in a rural setting. According to the facts available in the 1870s it had a population of 320 Armenians, and at the outbreak of the First World War 143 Armenians (25 households). There is a church and a school with 15 pupils in the village [37].

GRBO (now Kalkankaya): between Okhu (Bulgurcuk) and Tepe (Karakoçan). The village has 20 households with a mixed population. The Armenians live in six households in their own quarter [38].

HALALKOM (now Halalkomu): west of Palu itself, in a mountainous area. According to the 1870s statistics, there were 20 Armenian households; at the outbreak of the First World War there were 8. The village has a church (St Sarkis) and a school. 14 households of Zaza Kurds live alongside the Armenians [39].

HAVAV (now Ekinözu): two and a half hours north-west of Palu itself in a rural setting. Ten minutes away, to the west of the village, is the monastery of the Holy Mother of God Khaghtsrahayats, which is a diocesan establishment. The village consists of 207 households, has two churches (The Holy Mother of God and Holy Cathedral) and two schools with 260 pupils. The ‘Great Spring’ stream is to be found about a quarter of an hour north-west of the village. Havav is surrounded by the ruins of many old buildings and old cross-stones (khachkars), whose existence leads us to suppose that there was a town here in ancient times [40].

TSET (now Kapıaçmaz): two hours to the north-west of Palu itself. The village is in a valley and has 87 Armenian households. A church (St Toros) and a school with 55 pupils have been built here. The holy place called Haibad is to be found on a high place to the east of the village, and has a chapel in which a great cross-stone (khachkar) has been placed. It takes about half an hour to ascend the slope of the hill to this holy place. Apart from this, there are four other holy places around the village. One of them is Holy Cross, to the south. About 100 metres (325 feet) from it is Haibedkor, that in local dialect means ‘Haibad’s Sister’. On the western side of the village, in the direction of Haibad, is the ‘Dark Manug’ (or ‘Dark Child’) holy place, while on the eastern side there is another, whose name is not recorded [41].

KHAMBER SHEIKH or KHAMBASHEKH (now Kambersih): north of Isabeg, near the village of Kumbat (Kümbet). It is located in a rural setting and has a mixed population of about 30 households of Armenians and Kurds [42]. Rev Harutiun points out that the Armenians had left the village before 1915 [43].

MURCHOM MEZRE (now Karıncaköy): about 20-25 minutes south of Havav (Ekinözu) village in a rural setting. According to the information available in the 1870s the village comprised 44 households, while just before the outbreak of the First World War it had 20. It has a church (St Kevork) and a school with 18 pupils [44].

NADJARAN (now Baltaşı): on the left bank of the Aradzani River to the south-west of Palu itself. The village is built at the base of a hill and consists of 25 Armenian households and 10 Kurdish ones. It has a church (St Minas) and a school with 18 pupils [45].

NEKHRI or NERKHI (now Nirhi): half an hour to the north of Palu itself. The village is located at the foot of a large cliff named Khachkran, and the houses are built next to each other up a slope, giving the whole village unique aspect. It has a spring that, according to tradition, is good for healing deafness. The village has a church (The Holy Mother of God) and a school with 75 pupils. There is a large cross-stone (khachkar), known as the ‘blue cross-stone’, standing behind the church. It is carved from pumice stone and is about two metres (6 feet 6 inches) in height and one metre (3 feet 3 inches) wide. 62 households of Armenians live here. At the right of the village is a small room carved out of the cliff that was probably a hermitage [46].

NOR KIUGH (now Yeniköy): one and half hours west of Palu itself. The village consists of 21 Armenian households and has a church and school with 15 pupils [47].

NOR KIUGH MEZRE (now Yeniköymezreası): about three hours to the west of Palu itself. It is located on a high place and has 30 Armenian households. It has a church and a school [48].

NORSHNAG (now Beşpınar): two hours west of Palu itself. A small village with five Armenian households [49].

NBESHI (now Nipşi): one hour north-west of Palu itself. Its neighbouring village is Nekhri. It is located on a high place from which the Palu plain can be seen and is made up of 36 Armenian households. It has a church (St Garabed) and a school with 45 pupils. The ruins of St Boghos monastery are near the village. Nearby is the St Boghos spring, which has become a place of pilgrimage for Armenians and non-Armenians alike. There is another holy place near the village named St Tuman. Later on, Armenians from the town began to buy land in the village and sink wells. The geographical location of Nbeshi (Nipşi) provides the village with various conveniences. The climate is pleasing, it has plenty of water and is rich with its vineyards and gardens. In other words this village has all the resources to become a future town, especially as the new road from Harput to Erzurum runs close by [50].

SHINAZ (now Saraybahçe): South of Abrank (Köprüdere) village, between the town and Havav (Ekinözu) village. It is in a rural setting. It has an ancient small church (St Hagop). It consists of 54 Armenian households [51].

UZUNOVA (no longer exists): six hours west of Palu itself. It is located on the bank of the Aradzani River in a rural setting. According the information available in the 1870s the village was made up of 45 households of Armenians (360 people), while at the outbreak of the First World War there were 178 individuals. There is a church (The Holy Mother of God) in the village. The majority of the inhabitants are Armenian Protestants, who have their own prayer hall and school [52].

UZUNOVA MEZRE (now Uzunova): located near Uzunoba and is formed of 12 Armenian households. It has a church (St Sarkis) [53].

CHAIRI MEZRE (now Chayri Mezre): located near Nbeshi (Nipşi) village. It is made up of 13 households and has a church (St Krikor) and a school with 16 pupils [54].

BAGHIN (now Baghin): made up of about 102 Armenian households. It is four hours directly south of Palu itself. It had two schools, one named Aramian, with 140 pupils and a church (St Sarkis). The ruins of the ancient castle that was the seat of the rulers of Baghin are located one hour south of the village, as are those of the monastery of St Sarkis and the church of The Holy Mother of God [55].

BASHARAT (now Başarat): four hours west of Palu itself, in a valley. 12 Armenian households live alongside 10 Zaza Kurdish ones [56].

SAKRAT (now Yazıbaşı): north-west of Palu itself, near Shinaz (Saraybahçe). It is in a rural setting and has 75 households. It has a church (St Toros) and a school with 73 pupils. Two of Palu’s influential Kurdish beys, Ibrahim and Rushdi have had their palaces built in the village, forcing the villagers to build them as if they were serfs. The ‘Black Spring’ stream is well known [57].

SRIN (now Serin): south of Palu itself, in the wide Arin Dagh plain. It is about two hours distant from Baghin and is formed of 32 households, all Armenians. It has a school with 40 pupils and a church (The Holy Mother of God) [58].

SGHAM (now Pınartepe): about one and a half hours west of Palu itself. It is formed of 51 Armenian households, has a church (Holy Cross) and a school with 50 pupils. The chapel of St Garabed and St Boghos holy place are also located here [59].

DEVEDJI (now Deveci): about three hours north of Palu itself. It is in a rural setting and is formed of a mixed population of 15 Armenian and Kurdish households [60].

DEMIRDJI (now Demirci): north-east of Palu itself. It has a mixed population of 20 households made up of Armenians and Zaza Kurds [61]. Rev Harutiun points out that the Armenians had left the village before 1915 [62].

DILIMLI (now Tekardıç)a mixed village north-west of Tepe (Karakoçan), with about ten Armenian and Kurdish households in separate quarters. The village has a church and there is a holy place or pilgrimage site nearby called Sev Kar Baba [63]. Rev Harutiun points out that the Armenians had left the village before 1915 [64].

KENGERLI (now Fahribey): west of Palu itself, it consists of 28 Armenian households. It has a church (St Tovmas) and a school with 20 pupils [65].

KUMBAT (now Kümbet): about five hours north of Palu itself. It has 32 households, a church (The Holy Mother of God) and a school with 40 pupils [66].

KURDIKAN (now Gümüşkaynak): south-west of Palu itself with a mixed population of Armenians and Kurds. Six of the households are Armenian and have their own church (Holy Cross) [67].

OKHU (now Bulgurcuk): north east of Palu itself. It is in a rural setting and has a mixed Armenian and Kurdish population (25 Armenian households, 25 Kurdish) that live in separate quarters. There is a church (St Giragos) and a school with 40 pupils. The holy place of St Sarkis is to the east of the village and is a place of pilgrimage. There are many cross-stones (khachkars) around the village [68].

[1] Rev Boghos Natanian, Tears of Armenia or a report on Palu, Harput, Charsandjak, Djabaghchur and Erzindjan (in Armenian), 1883, Istanbul, page 13-14.

[2] Rev Harutiun Sarkisian (Alevor), Palu: its customs, educational and intellectual state and dialect (in Armenian), Sahag-Mesrob Press, Cairo, page 251, Natanian, op. cit., page 13-14.

[3] Mesrob Grayian, Palu: pictures, memoirs, poems and prose taken from the life of Palu (in Armenian), Catholicossate of Cilicia, 1965, Antilias, page 111.

[4] Ibid., page 207.

[5] Natanian, op.cit., page 32-33.

[6] Grayian, op. cit., page 38, Natanian, op. cit., page 84.

[7] Grayian, op. cit., page 40.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Natanian, op. cit., page 30, 41, 47-48.

[10] We are grateful for this information to Mr George Aghjayan who graciously transferred his unpublished work on Palu to the Houshamadyan’s editorial board.

[11] Grayian, op. cit., page 41.

[12] Ibid., page 42.

[13] We are grateful for this information to Mr George Aghjayan who graciously transferred his unpublished work on Palu to the Houshamadyan’s editorial board.

[14] Harutiun Tsakhsurian, History of the valley of Palu from ancient times to the present (in Armenian), published by Donigian, 1974, Beirut, page 253.

[15] Natanian, op. cit., page 94.

[16] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 253.

[17] Ibid., page 95-97.

[18] We are grateful for this information to Mr George Aghjayan who graciously transferred his unpublished work on Palu to the Houshamadyan’s editorial board.

[19] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 273.

[20] The distance from one place to another expressed in time is that required to reach it on foot.

[21] Raymond H. Kévorkian/Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l’Empire ottoman à la veille du génocide, Paris, Éd. Arhis, 1992, page 408, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 274. Natanian, op. cit., page 79.

[22] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 84.

[23] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 284, Natanian, op. cit., page 67.

[24] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 275, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 86.

[25] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 87.

[26] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 283, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 70.

[27] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 272, Natanian, op. cit., page 89.

[28] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 271.

[29] Natanian, op. cit., page 74, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 285, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[30] Natanian, op. cit., page 84, Sarkisian, op. cit., page 320.

[31] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 284, Natanian, op. cit., page 67.

[32] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 284, Natanian, op. cit., page 73.

[33] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 85.

[34] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 272.

[35] Natanian, op. cit., page 68, Tsakhsurian, page 284, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[36] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 272, Natanian, op. cit., page 74-75, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[37] Natanian, op. cit., page 86.

[38] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 284, Natanian, op. cit., page 69.

[39] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 85.

[40] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 60-64.

[41] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 275-277, Natanian, op. cit., page 83, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[42] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 285, Natanian, op. cit., page 71.

[43] Sarkisian, op. cit., page 320, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 285.

[44] Natanian, op. cit., page 66-67, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Sarkisian, op. cit., page 320, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 279.

[45] Natanian, op. cit., page 88, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 272, Sarkisian, op. cit., page 320. It should be noted that, according to Sarkisian, Nadjaran’s chuch was called St Nshan.

[46] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 77-78, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 272.

[47] Natanian, op. cit., page 86, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[48] Natanian, op. cit., page 86-87.

[49] Ibid., page 87.

[50] Grayian, op. cit., page 43, Natanian, op. cit., page 77-78, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 273-274.

[51] Natanian, op. cit., page 79, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 274.

[52] Natanian, op. cit., page 83, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[53] Natanian, op. cit., page 84-85, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[54] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 274, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[55] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 269, Natanian, op. cit., page 87-88, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408. See also: History of the house of Baghin, published by the Baghin Village Reconstruction and Educational Union, ‘Hairenik’ Press, Boston, 1966.

[56] Natanian, op. cit., page 85, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[57] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 274, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 80-81.

[58] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 271, Sarkisian, op. cit., page 320, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[59] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 274, Natanian, op. cit., page 80, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[60] Natanian, op. cit., page 73-74, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 284.

[61] Natanian, op. cit., էջ 73, Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 284.

[62] Sarkisian, op. cit., page 320.

[63] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 284, Natanian, op. cit., page 70.

[64] Sarkisian, op. cit., page 320.

[65] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[66] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 285, Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408, Natanian, op. cit., page 71.

[67] Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.

[68] Tsakhsurian, op. cit., page 279-282, Natanian, op. cit., page 69. Kévorkian/Paboudjian, op. cit., page 408.