Arapgir Kaza: Churches, Monasteries and Holy Sites

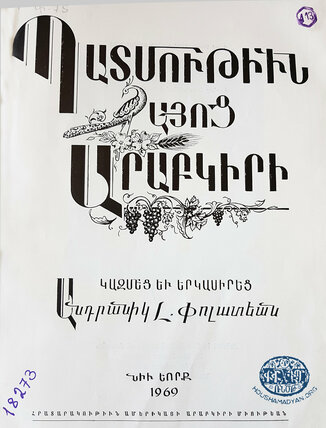

Author: Khazhak Drampyan, 05/09/2019 (Last modified: 05/09/2019) - Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

This article focuses on the monasteries, churches and holy sites that were once located in the Armenian towns and villages in the kaza (district) of Arapgir and the stories/fables surrounding them that are to be found in the written recollections of geographers, ethnographers and church functionaries.

We take a specific look at the town of Arapgir and fifteen villages (Ambrga, Shepig, Dzak, Grani, Hatsgni, Khoroch, Mashgerd, Saghmga, Vank, Koushna, Vaghashen, Anchrti, Vaghaver, Ehnetsik, Dzablvar) once populated by Armenians. We have also studied the biographies and activities of clergymen who served in the district.

The Kaza of Arapgir was located in the Vilayet of Mamuratul Aziz-Harput (Kharpert/Harput), founded as an Ottoman administrative unit in 1880. The Kaza of Arapgir borders the Kaza of Agn to the north, Dersim to the east, Gaban-Maden to the south, and Sivas to the west. [1]

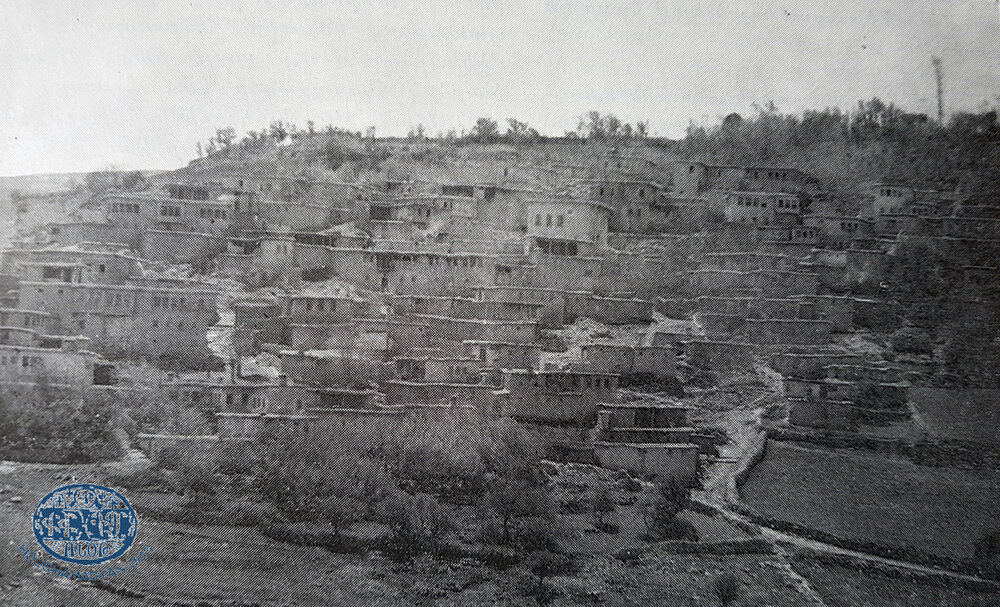

Town of Arapgir

The town of Arapgir had six apostolic churches – St. Asdvadzadzin or the Mother (Main) Church, which was the biggest and most ornate of the six; St. Hagop, St. Kevork (in the Keshishler neighborhood that was used as a holy site); St. Mamas; and St. Lousavorich (in the Shahroz/Ara Giavour neighborhood). They were a half hour’s distance from one another. [2]

St. Asdvadzadzin

This church was located on a promontory in the center of town. It was a large monastery, made of stone and lime, with a wooden roof. Separate schools for boys and girls were located close by. The diocesan building was located in the middle. The structure could accommodate 4,000. Prior to its renovation, it had five altars with separate arches and one crucifix.

The church’s interior was richly adorned with silver lamps, gold and silver religious books and crosses, beautiful vestments, chalices, etc. They were all purchased with funds donated by the faithful. On Sundays and holidays, donation plates would be placed outside the church entrance. The faithful would donate gold and silver coins to renovate the church, care for the needy, to operate the school and the diocesan office. [3]

Donation plates would also be passed around during vespers and liturgical services. The money was used to pay the priest celebrating the liturgy, the altar servers and the sexton, to pay for the upkeep of the cemetery, and to pay for the oil used to light the lamps (Yughakin). [4]

A large cemetery, surrounded by mulberry trees and bushes, was located near the church. A small spring flowed by the entrance. [5]

Pakhdigian writes that people once said that another monastery stood on the site of the St. Asdvadzadzin monastery in the Arapgir neighborhood of Keshishler. [6]

Most of the stores and the inn located in the market to the south of the Holy Mother Church belonged to church. Arapgir residents would gather in large numbers every Easter on the roof of the inn and have egg fights under the mulberry trees. In 1894, on the Friday before Easter, thousands of Arapgir residents, as per tradition, assembled on the inn’s roof. It suddenly collapsed from the weight. Forty people died that day. Their remains were removed from under the rubble. It was a sad Easter Sunday. [7]

Church Renovations

The Mother Church was renovated four times. According to Poladian, the co-primates Tateos and Aleksanios of Tokat, served for six years in Arapgir and proposed that a new church be built on the site of the old one. They ran into difficulties. They asked for help from one Kasbar Amira from the nearby village of Mashgerd. The amira was well liked by Sultan Mahmut II (1808-1839). The amira raised the issue to the sultan who issued an edict allowing the church’s renovation. The work lasted two months and was made possible by a donation of 30,000 ghouroush/tahegans by Vartabed Tateos. The donation was unprecedented for the time. [8]

We see an inscription about the renovation work in a May 26, 1893 article, penned by teacher H.B. Manuelian, in the Constantinople paper Arevelk.

This church was restored in the name and to the glory of the Holy Mother of God. At the forceful order of Sultan Mahmud, the mighty king that makes the world tremble. And through the efforts of the great Garabed [Balattsi] Rapounabed [Patriarch] of Constantinople, with the intercession of the nation’s amiras, Eternal benevolent clan, with the council of our Amira, Mahdesi Kasar, and with the efforts and donations of our compatriots in Arapgir. [9]

As we see, the inscription mentions the services rendered by Kasbar Amira. But there is no mention of Vartabed Tateos, who donated most of the money for the restoration. We read about his donation in the writings of Vartabed Moushegh. [10]

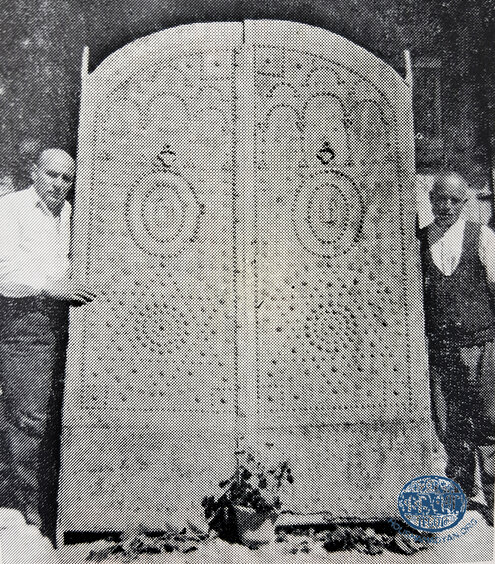

1) The door of the Holy Mother Church. On its left is Sarkis Miranshahian, and on its right is Hadji Kayfedjian (Source: Antranig Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, New York, 1969).

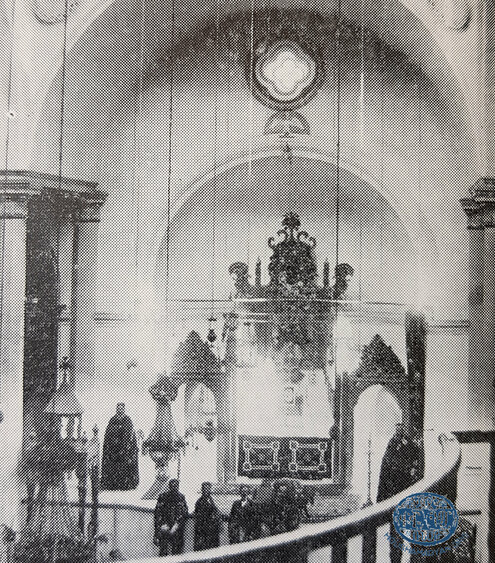

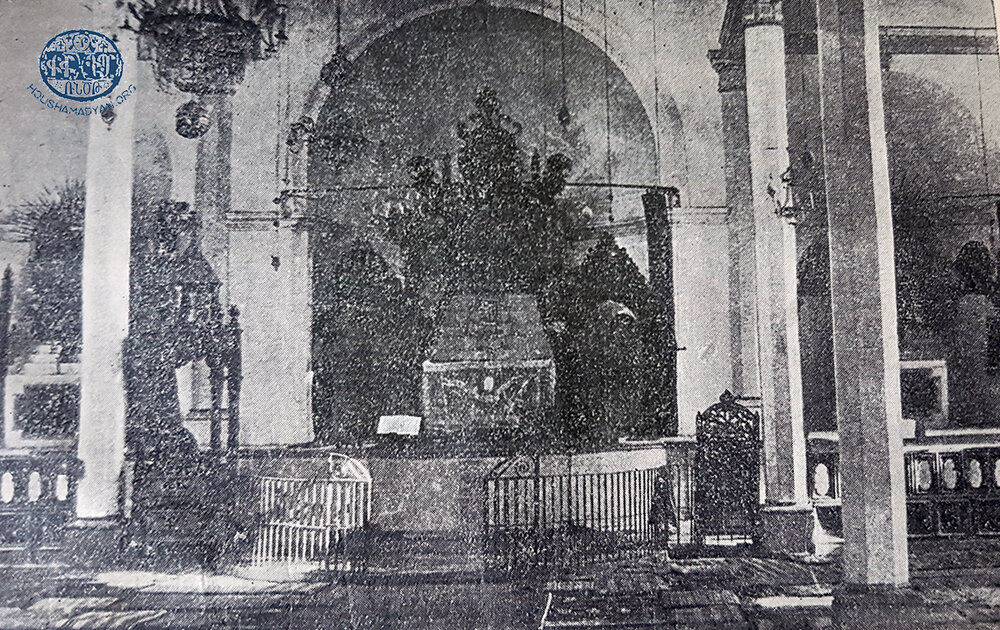

2) The main altar of Arapgir’s Holy Mother Church (Source: Antranig Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, New York, 1969).

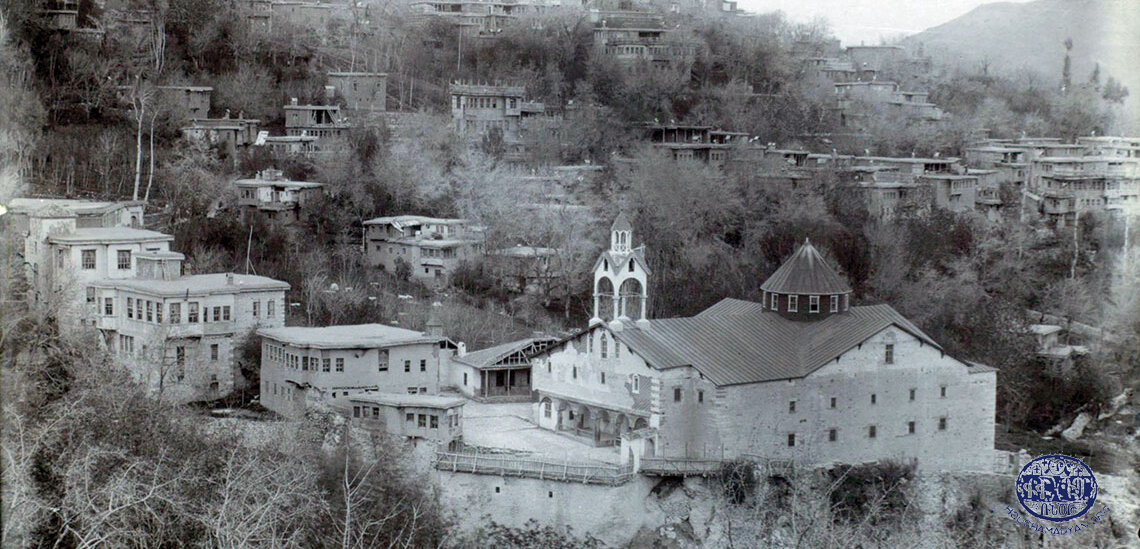

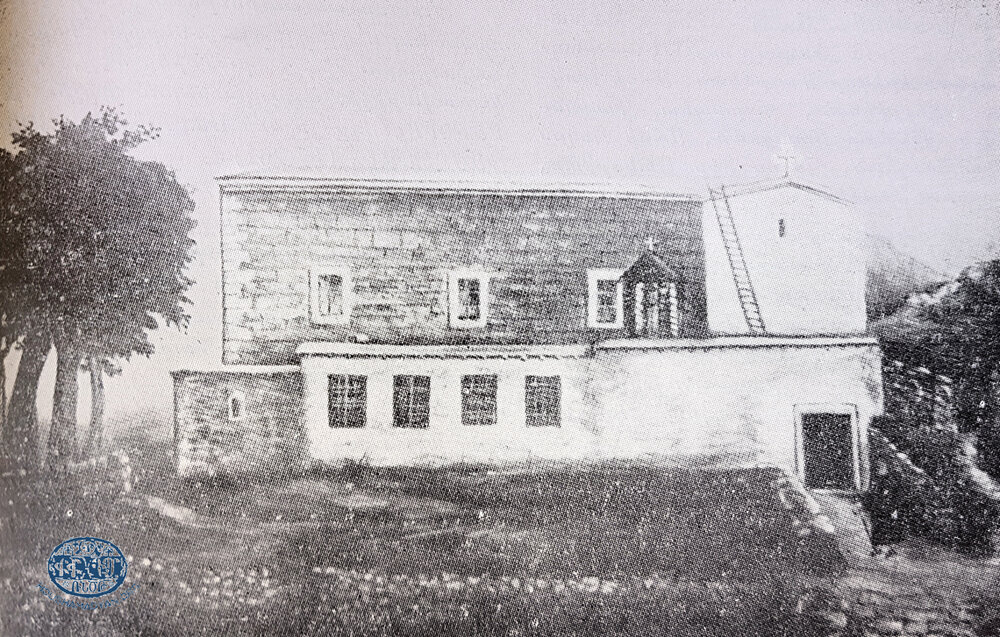

Arapgir: St. Asdvadzadzin Church (center). Built in 1830s. Changes to the roof first made in 1893. This photo was probably taken after the first construction work was over. It was an expansive church that had three galleries for female worshipers. The church had three entries; two facing west and one, north. The roof was completely renovated post 1907. The photo is pre-1907 and shows the roof in its prior state. Photograph by Kevork/George Djerdjian (Source: George Djerdjian photo collection).

According to Maghakia Ormanian, Garabed Rapounaped mentioned in the renovation inscription was the 62th Patriarch of Constantinople, who, Poladian believes, could not have remained indifferent to the renovation of the Arapgir church. Ormanian uses the name Lord Garabed of Balat to describe him. [11]

The second renovation of Arapgir’s Holy Mother Church took place in 1893, when Housig Kachouni was vicar. In order to renovate the roof, a regional council of national leaders was formed that instructed the clergy and architects to inspect the entire church structure. A Greek architect drafted a renovation plan that cost 1,500 gold pieces. This was a huge sum. H. Manuelian describes the sum in the following words.

“Some, perhaps, will find the amount extreme. At issue is merely the conversion of the dirt roof into a new one, where the old walls will remain, along with the altar, etc. However, when we consider the expansiveness of this sacred institution, of which there are only three or at the most four in our midst, it is easy to be convinced that the specified amount doesn’t exceed the bounds of normalcy.” [12]

The local government created many barriers to the roof reconstruction, particularly regarding the height of the dome. After receiving the notice of two investigators sent from Harput/Kharpert, a construction permit was finally issued, allowing Arapgir residents to start the work. [13].

The third renovation of the church took place in 1902, during the era of Father Moushegh Seropian. Construction material was brought from the town of Anti [an ancient Arapgir settlement from whence the population migrated and founded the city of Arabkir] and the surrounding villages. Until 1902, the church was standing on 24 pillars, decorated with oil paints and adorned with frescoes portraying Bible stories. It is said that these images immediately captured the attention of the people [14].

The fourth renovation tool place during the time of Meroujan Vartabed Ashkharouni. They affixed an oil painting with plaster on six columns in the church, replacing the previous 24. There were twelve windows on the church roof. While removing the 24 columns, a number of crosses, church items, bones and skulls appeared. Three altars replaced the previous five. The main altar was in the middle, and above it was a marble dove, its beak directed to the baptismal font. [15]

The cathedral had three upper galleries for women. The upper one was reserved for girls. There were balconies on the northern and southern walls of the gallery. The church had three entrances, of which two looked to the west and one to the north. [16]

For this costly renovation, Vartabed Ashkharouni sought the assistance of Arapgir natives living abroad, especially in Egypt. They made significant donations to renovate the Mother of God Church. Two letters about the donations are particularly interesting. The first is the letter of Arapgir native Bedros Garabedian to Primate Mgrdich Vartabed Aghavnouni of the Armenian Church in Egypt, in which he reveals that he’s donating 200 Ottoman gold pieces to renovate the church’s roof on condition that Arapgir national leaders contribute the same amount. [17]

The second letter is an official bulletin, drafted by the Cairo Political Assembly, that appeared in the records of the fundraising committee. From it we learn that Vartabed Ashkharouni sought the help of his spiritual brother, Mgrdich Vartabed, noting that local funds weren’t sufficient and there was a need for Arapgir natives who had left the homeland to carry out fundraising as well. [18]

Pillaging of the Church

Brigands pillaged the Mother of God Church in 1871. The incident was widely covered in the local press. On the night of March 31, 1871, three Kurds broke the iron bars of the church, entered through the window, and stole the precious items inside. The estimated value of the stolen items was 30,000 ghouroush/tahegans. Church sacristan Father Mardiros, from his adjacent room, heard the noise and called out for the church sexton. The latter entered the church and saw the robbery taking place. The bandits fled the scene, probably after hearing the priest’s shouts. Upon hearing the news, Hadji Djihan Mamasian Agha linked up with Sarkis Khahvedjian and Hadji Ohan Semerdjian and they went looking for the Kurds. Reaching Gebik, Hadji Djihan chased after the Kurds for six or seven hours. The brigands tried to defend themselves but were unable to use their only gun due to the wet weather. The police arrive on the scene and a group of Armenians hand over the Kurds to them. The Armenians, led by Hadji Djihan, return to the church carrying the stolen items on their shoulders. The kaymakam (provincial district governor) invites Djihan Agha to the Medjlis and publicly congratulates him for his bravery. The robbers are taken to Gaben-Maden and are interrogated. They confess to pillaging 48 churches and one mosque. The government seizes their property and jails them. [19]

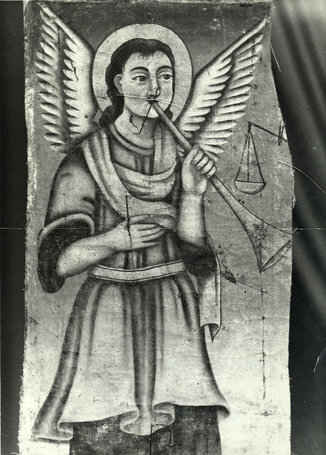

1) One of the icons displayed on the altar of the Holy Mother Church, the oil painting of Archangel Gabriel. The identity of the painter is unknown (Source: National Archives of Armenia, Yerevan, collection 447, table 1, item 22).

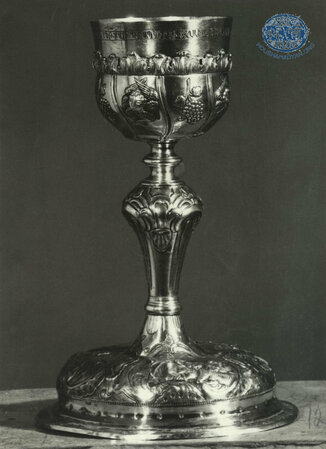

2) The chalice of Arapgir’s Holy Mother Church. It is currently kept in the museum of the Mekhitarist Order of Vienna (Source: National Archives of Armenia, Yerevan, collection 447, table 1, item 22).

3) One of the icons displayed on the altar of the Holy Mother Church, the oil painting of the Holy Virgin. In 1955, Ardashes Habeshian visited Arapgir from Aleppo. There, he received this painting, which was the altarpiece of the church, from Baghdasar Der-Sahagian. The painting is dated 1904 and was the work of Archbishop Mampre. The painting is damaged (Source: National Archives of Armenia, Yerevan, collection 447, table 1, item 22).

The Mother Church’s Exiled Chalice

The Arapgir Mother Church was pillaged during the 1915 Genocide. None of the church’s property was saved except for a silver gold-leafed chalice that travelled from country to country, from person to person, and finally wound up at the Mekhitarist monastery in Vienna. Vartabed Yeprem Boghosian gives the following description of the chalice after reporting the news in the Nor Arapgir bulletin. [20]

“The chalice is 301/2 cm tall, the circumference of the cup is 30 cm, and the diameter is 9 cm. The circumference of the chalice pedestal is 56 cm and the diameter is 171/2 cm. The chalice is made of silver, and the inside and outside are gilded. The grapevines are also gilded with the leaves and lintels of the vine on the cupboard. The chalice itself is a work of art, handcrafted by Armenian jewelers. There are ornaments around the upper part of the chalice or around the cup, around the middle or by the handle, as well as on the bottom ends of the base and on the upper face. Angels with six wings are depicted around the cup. The instruments and objects remind us of the sufferings of Jesus - the plowing pillar, the whip, the washbasin and vase used by Pilate to wash his hands, the hammer, tongs and nails used by those who crucified him, the crook and the gems, the centurion’s spear, the wood over the cross, and so on. The base is decorated with three bunches of wheat leaves and three branches of fruit and berries, and the bottom edges are decorated with ornaments. In the upper part of the chalice, around the glass, and on the bottom, there are also Armenian inscriptions. There are also three inscriptions on the cup of the chalice.” [21]

Take, eat

Get drunk of it

I am the bread of life [22]

There are the following three inscriptions on the base of the chalice.

- A remembrance of Kalsdian Mh [mahdesi] Mardiros Agha, Arapgir Mother Church, 1897

- A remembrance of Aroutiun Amir, By the hand of Avedik

- A remembrance of Agent Melkon of Zarbkhan

The chalice is well preserved. There are no broken or crushed parts. There’s a one-centimeter long and one-millimeter wide small hole is at the edge of the lower part of the base. [24].

Other Church Items

H. Aleksis writes that the Mother Church had many church items - silver lamps, golden and silver gospels, crosses, gorgeous vestments, and so on [25].

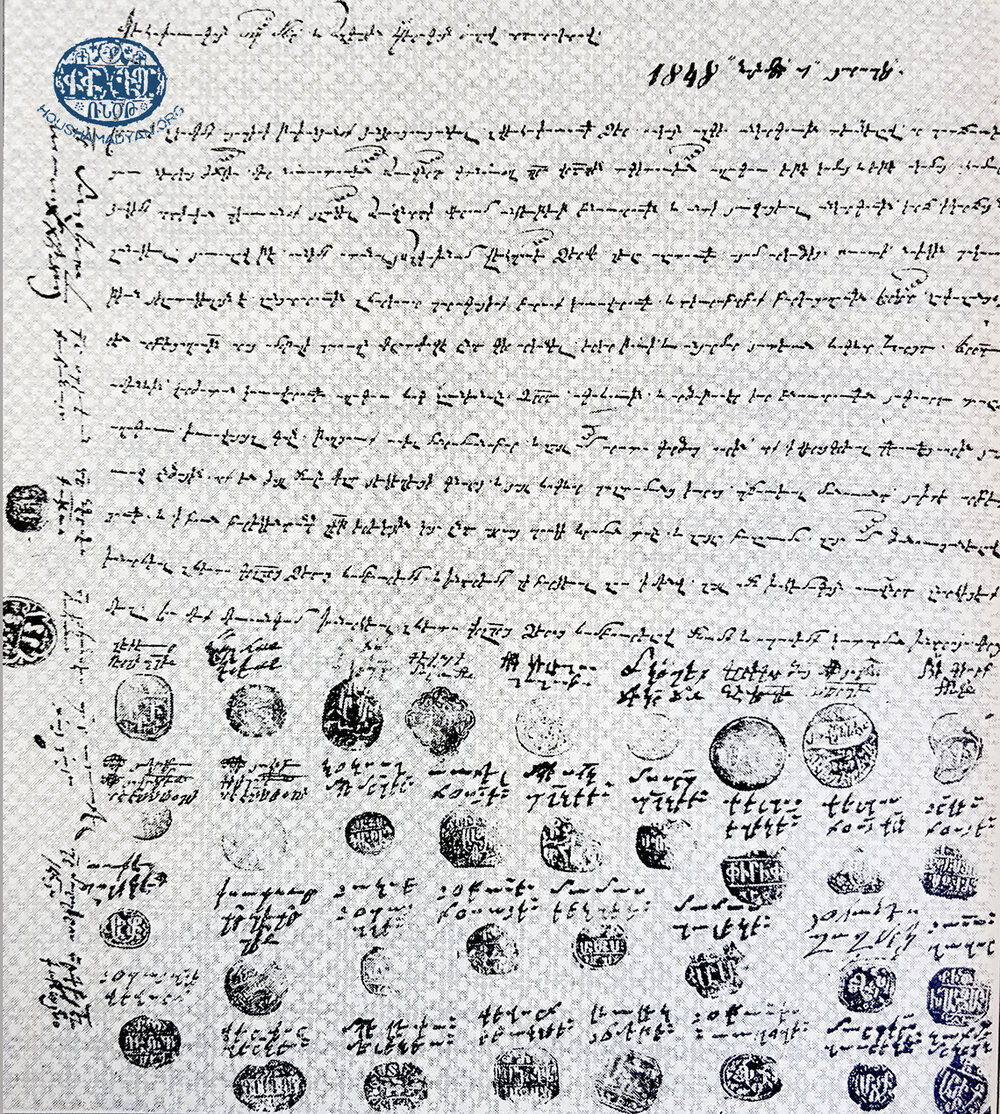

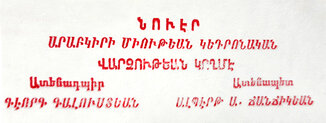

The original of a letter dated November 7, 1848, which bears the signatures and stamps of priests and community leaders from Arapgir. The letter was sent to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Armenian National Council, protesting against Prelate Bedros’ actions, mercurial temperament, and predilection for drink (Source: Antranig Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, New York, 1969).

St. Hagop Church

Poladian notes that the St. Hagop Church in Arapgir was led by a strict and thick-armed celibate priest. Poladian also writes that it was located in the Keshishler neighborhood of Arapgir and was called Keshishler Monastery. At that time, it was a monastery and owned large tracts of land and other property. Pakhdigian writes that "the original monastery is an infinite space on the two sides of the Kar-Pnag road, that extends to the Mansoub Dedeh (St. Mesrob) of Shahad village, Ambrga, Amadoun, Dishdereg, Hntsanag, Oughouzlar and Galoug. [26].

St. Prgich Catholic Monastery

The St. Prgich (Holy Savior) Catholic Monastery was a wooden structure. A school for Armenian Catholics was attached to the monastery.

There’s also a recollection that Vartabed Abraham, the religious leader of Armenian Catholics in Arapgir, had converted the barn of his rented house into a Catholic chapel and school. There was another house in Arapgir, acquired by Archbishop Andon Hasounian for 32,000 ghouroush, to turn it into a church, however. Poladian notes, however, that at that time it was still being built. [27].

The monastery, in ancient times, had been a place of pilgrimage where many religious monks lived. A school of literature and teaching also existed there.

Gh. Indjidjian writes that St. Prgich Monastery refers to the district of Agn and calls it St. Yerevoumn or St. Yerevan. He writes that a spring, named Cheopler, bubbled out of the ground below the monastery.

S. Eprigian calls the monastery St. Yerevoumn or St. Prgich, and also believes it was located in the Agn district. [30] The monastery is closer to the district of Agn, however, as we see from the above-mentioned manuscript, the territory of the Arapgir diocese was much more extensive in 1446 and St. Prgich Monastery was included in its jurisdiction, otherwise the words “In the land of Arapger” wouldn’t have been noted in the manuscript. According to S. Eprigian, the monastery was only included in the Arapgir district in recent times, and since it didn’t have any monks or brothers the primates of Agn also, at the same time, served as the monastery’s abbots. [31]

St. Mamas Church

There was a ruined church in Arapgir named St. Mamas. Karekin Srvantsdiants writes that it was destroyed in 1878 and that it was close to the St. Pilbos Apostle Monastery. Drtad Balian considers it to be the Malatia Monastery and Kevork Aslanian notes that Malatia did not have a monastery with that name and says the clergyman may have jumbled the names. [32].

Hamazasb Vartabed Vosgian says that St. Mamas Monastery belonged to the village of Vank, from which the village got its name [33].

1) The ruins of the Saint Mamas Church (Sources: National Archives of Armenia, Yerevan, courtesy of Dirk Roodzant).

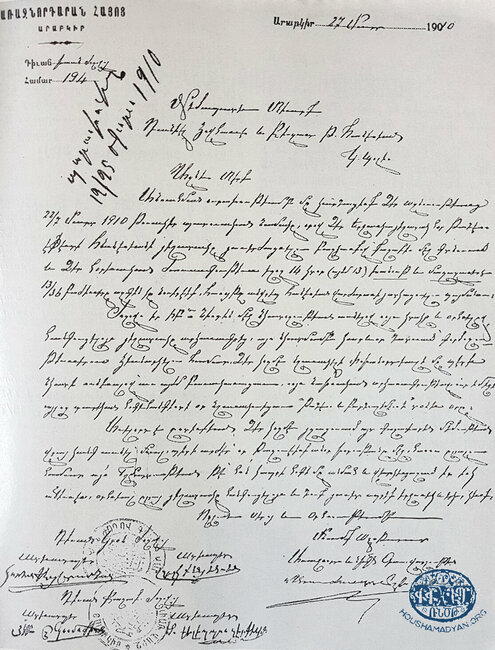

2) This letter bears the letterhead of the Armenian Prelacy of Arapgir, the number of the document and the date, the signature of Prelate Meroujan (on the right), as well as the names and stamps of the members of the Prelacy’s religious and secular boards (Source: Antranig Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, New York, 1969).

St. Illuminator Church

The St. Illuminator Church was located in the northern part of Arapgir, in the Shahrozi/Sra Giavour neighborhood. Sadly, there is no information about the church. [34]

Protestant Church

Armenian Protestantism in Arapgir took hold in 1840-1859. The first missionaries were John Clark, Dunmore, Richard and Balet (?), who founded a large church and school for Protestants in Arapgir. By 1858 the local Armenian Protestants had built a small church in the same Arapgir neighborhood as St. Illuminator’s. [35]

Among the Armenian and foreign pastors who visited the Arapgir district are: Pastor Asadour Nigoghosian of Peri (Dersim) who visited the Arapgir district in June 1901. Drtad Tamzarian, pastor of the village of Perchendj (located in the plain of Kharpert) who visited the Arapgir district in January 1902. Kavmeh Ablahadian, who visited the Arapgir district in June 1902. Rev. G.K. Brown, a travelling pastor of Kharpert missionary, who, along with Miss. Bush, preached on two occasions in the Arapgir district in 1901. In the absence of pastors, doctors Michael Hagopian and Haroutiun Hekimian preached in the Arapgir district. [36]

Pilgrimage Sites in Arapgir

Arapgir had 3 pilgrimage sites: St. Kevork, St. Takouhi and the brother, St. Arakel.

• The St. Kevork church/pilgrimage site was located in the northern side of the city. Some believed that St. Kevork was beheaded there and that his skull was still there, under the rubble of the ruined chapel. There was a basin there, and the faithful would fill it with water and bathe in it to cure what ailed them. [37].

• St. Takouhi was located at the summit of Mt. Shahroz. St. Arakel was at the foot of the mountain. People would visit these sites to cure themselves of childhood diseases, and mothers would visit if they lacked an adequate supply of breast milk. [38]

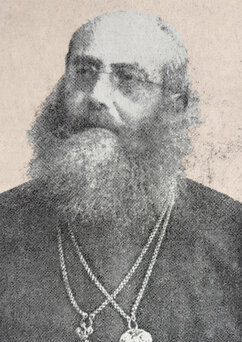

Clergymen of Arapgir

Touching upon the history of Arapgir city clergy, Pakhdigian writes that many priests once lived in the Keshishler neighborhood of Arapgir. (Keshish is the Turkish for priest). There were many families in the district of the Iretsian clan, a name that originated from the Armenian yerets (elder). At the start of the second half of the 19th century there were sixty households in this neighborhood. In Pakhdigian's time, right before the 1915 Genocide, only one house remained. There are no monasteries between Akpounar and this neighborhood, or the mention of any except in the field called Moses Agha, located between the villages of Keshishler and Ambarga, where, during the plowing season, censers, stone crosses, and other church objects were uncovered. [39]

- Father Yeznig Balouni (secular name, Garabed Keoseian) was born in 1854 in Arapgir. He was educated at the Arapgir National School, and then served as the sacristan at the Mother Church. In August of 1886, at the hands of Arapgir Primate Father Yeznig Abahouni, he was ordained a priest and was christened Father Yenznig Balouni. He was ordained with Father Housig Kachouni. As a priest he served in Arapgir and was sentenced to exile as a revolutionary in 1894. He sought refuge in Cairo in 1895, lived in Cairo and worked there until the end of his life as a priest at the Holy Mother of God Church [40].

- Mgrdich Der Bedrosian was the son of Father Bedros. He sang in the Arapgir Mother Church and taught music and mathematics at the school. He was the youngest of the three adopted sons of Bishop Mampreh. He received an education at the St. James Monastery in Jerusalem, under the direct supervision and care of the Bishop Mampreh [41].

- Melkon Melkonian, born in 1874 in Arapgir, received his primary education at a local school. He worked as a teacher’s assistant at the Arapgir’s St. Illuminator’s School and later as a chief instructor at the Yegavian and Mother schools located in Arapgir’s Shahroz neighborhood. He served as sacristan at Arapgir’s Mother Church and received four teaching degrees from the Bishop Karekin Khachadrian. He then served as a deacon at the same church. [42]

- Rev. Mardiros Siraganian: Born Arapgir, 1863. He graduated from the Euphrates College and served as a pastor at Protestant church in Arapgir’s St. Gregory the Illuminator neighborhood. He also served in Shepig and Mashgerd. He was killed in 1895 during the Hamidian massacres [43].

- Pastor Garabed Melkonian: Born Shepig, 1867 He graduated from Euphrates College. Served as a teacher and a Protestant pastor in Arapgir and Agn. [44]

- Pastor B. Garabedian: Pastor of the Protestant church in Arapgir’s St. Gregory the Illuminator neighborhood. Killed during the 1915 Genocide. [45].

- Pastor Sarkis Gralian: Pastor of the Protestant church in Arapgir’s St. Gregory the Illuminator neighborhood. Killed during the 1915 Genocide [46].

- Also mentioned as Protestant clergymen are: Pastor N. Nigoghosian, Hampartsoum Kevorkian, Bedros Khachadourian, S. Echmelian, Hovhannes Ghazarian and Krikor Tamzarian. [47]

Ambrga/Kayakesen Village

This half Armenian populated village was located south-east from Arapgir town, overlooking a valley. The town of Amadoun, which was a historic town according to villagers, was not far from Ambrga. [48]

St. Nshan Church

Ambrga had a church named St. Nishan, which was plundered and burnt in 1895, and was never rebuilt. Village residents traveled to Arapgir for their spiritual needs. [49]

The Pilgrimage sites of Ambrga Village

- The village had a chapel called Kilisedjouk, located opposite the village of Amadoun. Every year, during the plowing season, antiquities were unearthed. There was a cemetery near the chapel, which, according to locals, was Greek. [50].

- Ambrga was rich in water springs. There was a spring called Khachaghpyur in the village. On the holiday of the Holy Cross, pilgrims from the town and surrounding villages gathered at the spring. The faithful would bathe in the spring in the hope of being cured of various ailments. They would then tie pieces of cloth to the abundant white honeysuckle plants along the spring. [51]

- The Manoug Aghpyur (Child Spring)was known as a pilgrimage site where the Armenians and Turks bathed three times, to cure the shakes. Above the spring was the “Vari baghchayin magharan” (Lower garden sifting room). It is a spacious cave-shaped place with a circular pillar. People would visit the spring to ward off whooping cough. Pilgrims would circle the column three times. [52]

- The waters of the Khochrig Spring were well-known for healing wounds. [53].

- Teghnoud Spring, [probably derived from the words “tegh” (medicine) and “oukhd” (vow)], cured all types of pain. [54].

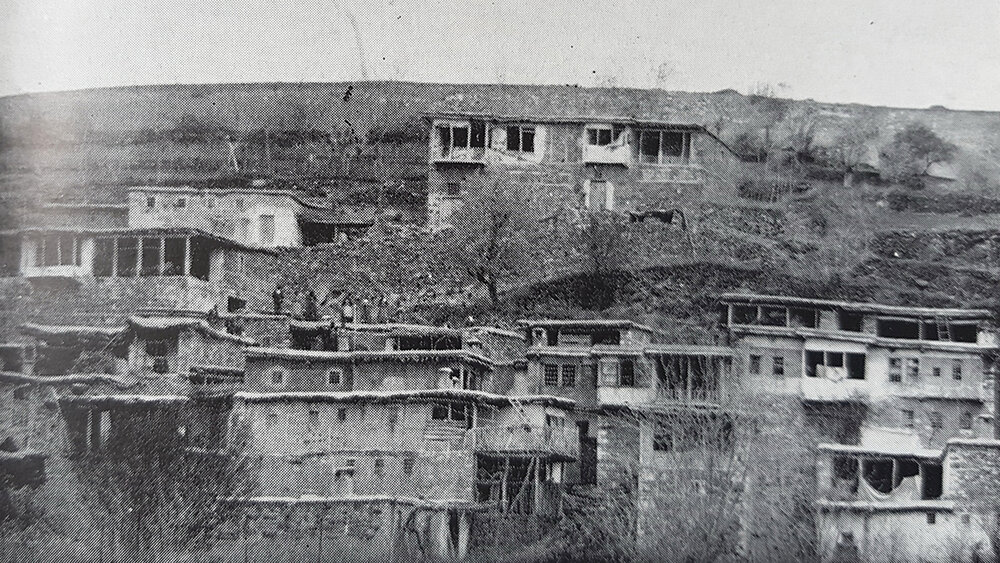

Shepig/Yaylacık Village

Shepig village was located on the slopes of a mountain, two kilometers to the north of Arapgir. [55]

St. Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God Church)

The Holy Mother of God Church in Shepig was burnt to the ground during the 1895 Hamidian Massacres [56].

Protestant Church

There was a Protestant church in the village of Shepig constructed by Shepig native Pastor Melkon Minasian, with the assistance of residents and missionaries. Minasian hadn’t yet been ordained when the church was built. [57]

There’s a notice in the Missionary Herald monthly magazine about the construction of the Shepig Protestant church. On December 7, 1957, Arapgir missionary Richardson writes that a church of unequalled beauty in the region was built in Shepig at the cost of 40,000 kurush, a sum equal to $1,600. The advent of Protestantism in Shepig caused a number of regrettable incidents. Disputes between the Apostolic and Protestant churches increased in frequency. The Armenian Apostolic Church tried to halt the spread of Protestantism but to no avail. The new church had secured its small but powerful flock in Shepig since it was based on an educational system. [58]

Of note is the fact that the local Apostolic priest, Father Mardiros, later converted to Protestantism. [59].

It is also worth mentioning that a large number of Euphrates College graduates came from Shepig. Some became pastors in the village. [60].

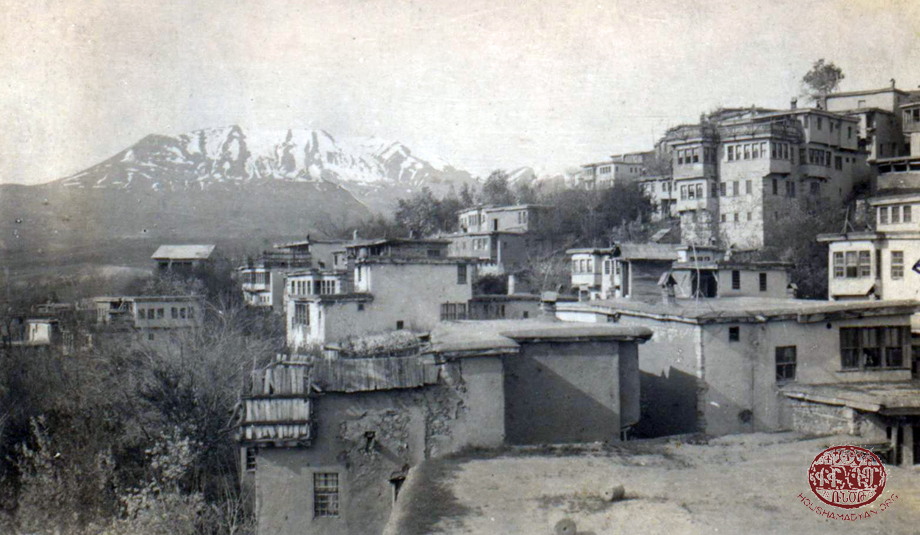

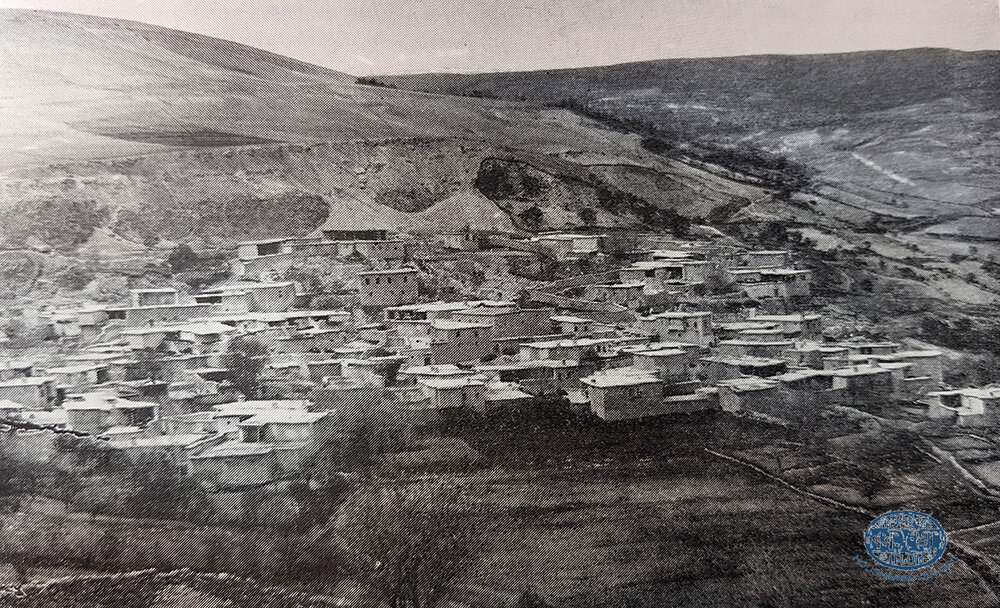

A panorama of the village of Shepig (present-day Yaylacık) (Source: Antranig Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, New York, 1969).

Shepig Village Pilgrimage Sites

The Pilibos Arakel pilgrimage site was located on the northern side of Shepig, on the bank of the river. It enjoyed great respect from Armenians and non-Armenians alike. Nomadic tent dwelling kizilbash Kurds and Turks from the surrounding villages also visited the site. It was said that the site returned the pilgrims from a state of alienation/of being away from the homeland, that it cured ailments, that it comforted the relatives and friends of the deceased, that it made wishes come true, that it save those possessed by the devil and warded off evil spirits. [61]

Once a year, in autumn, Arapgir residents would travel to Pilbos Arakel. There would be hundreds of wagons carrying people and animals to sacrifice. Others would make the trek on foot. Upon arriving, some of the pilgrims would descend to the sanctuary and kiss the stones, describing their pains and afflictions until sunrise. Then, everyone would welcome the sun with the words, "Good Light, Good God." This pilgrimage lasted three days, from Friday to Sunday. The pilgrims would return home spiritually refreshed. [62]

The ruined pilgrimage site was located on the bank of the river, overlooking a slope. On the other bank of the Vosgekedag River was the village of Tarkhanig or Diranig, at the foot of which there was a ruin fortress. The kizilbash Kurds living in this region, who treated the Armenians and their holy sites with respect, would relate that the staff of their patriarch (dede) was in that fortress. They would say that the fortress was built during the deportation of Senekerim. Pakhdigian concludes that a prince called Diranig built the fort and named it after himself. Then, according to the accepted ancient custom, he built a monastery named Pilbos Arakyal, that was later corrupted into Pilbos Arakel [63].

There is a myth about the rocks towering over of the Pilbos Arakel site. It is said that there once was a magnificent monastery at the site that was run by pious clergymen. One day, one of the officials of Ashodga (a nearby village) sent a man to these clergymen, inviting them to attend a banquet he was throwing in his palace. The clergymen refused to participate in worldly celebrations. The irate official dispatched cavalry to the monastery to bring them by force. A group of clergymen fled into the forest, but the horsemen followed and attacked them. One of the priests beseeched God to turn him into stone rather than to fall into the hands of the senseless attackers. The request is immediately fulfilled, and the priests turns into stone. [64].

Poladian says that the site hadn’t been destroyed for a long time. The adjacent fields belonged to the Turks [65].

Shepig Village Protestant Clergymen

- Reverend Khachadour Boghosian: Born in Shepig. Lived in Kharpert and then in Constantinople, from where he left for the United States and settled in Fresno, California, where he died. [66]

- Very Rev. Armenag Siraganian: Born in Arapgir. Graduated from Euphrates College in 1909. Preached in Shepig, Vaghaver, Cairo and Izmir. Later engaged in pharmacy business. Died in New York.[67]

- Very Rev. Mardiros Siraganian: (see biography in the Clergymen of Arapgir section)

- Father Baghdasar Barasatian served as the pastor of the Shepig church (most likely the Holy Mother of God Church). In 1912, he emigrated to Argentina.

Dzak Village

The village of Dzak was located on the bank of the Vosgekedag River, four hours walking distance to the northeast of Arapgir. [68]

St. Nshan Church

This large church was located outside the village. There was one, and sometimes two, priests serving in the church. Poladian notes that according to the villagers, the church was a 120-year-old structure built by Greek builders brought in from Agn. It is said they used stone and lime and followed a blueprint. The church wasn’t striking from the outside, but it had a magnificent inner court with three symmetrical arches and the altar. The arches stood on four thick pillars. The marble font was located in an open square niche. Off to the side a bit, the church’s thick door separated the church from the vestry that dovetailed into the roof of the school. The vestry was where priests and acolytes dressed for religious services.

The Dabrni stone fort was located in Dzak, along with the Kar Poul Fortress and the ruins of the St. Nshan Monastery. The new St. Nishan Church, named after its ruined predecessor, stood for 500 years. [70].

Pakhdigian says that the village of Dzak originally took shape near Dabrni, Nerkin Poul, and the St. Nishan Monastery, when three families settled there. [71]

S. Amadian mentions that the church had two priests. [72]

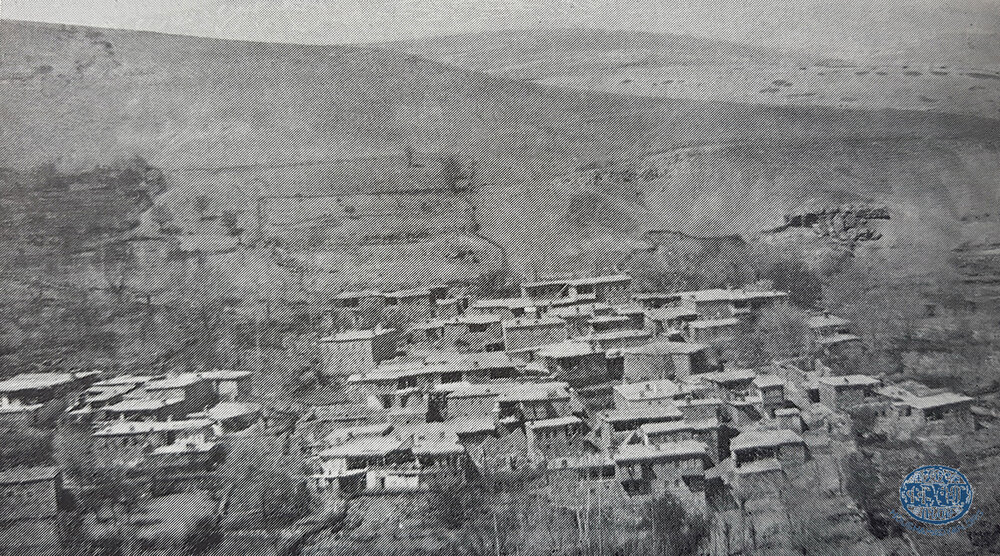

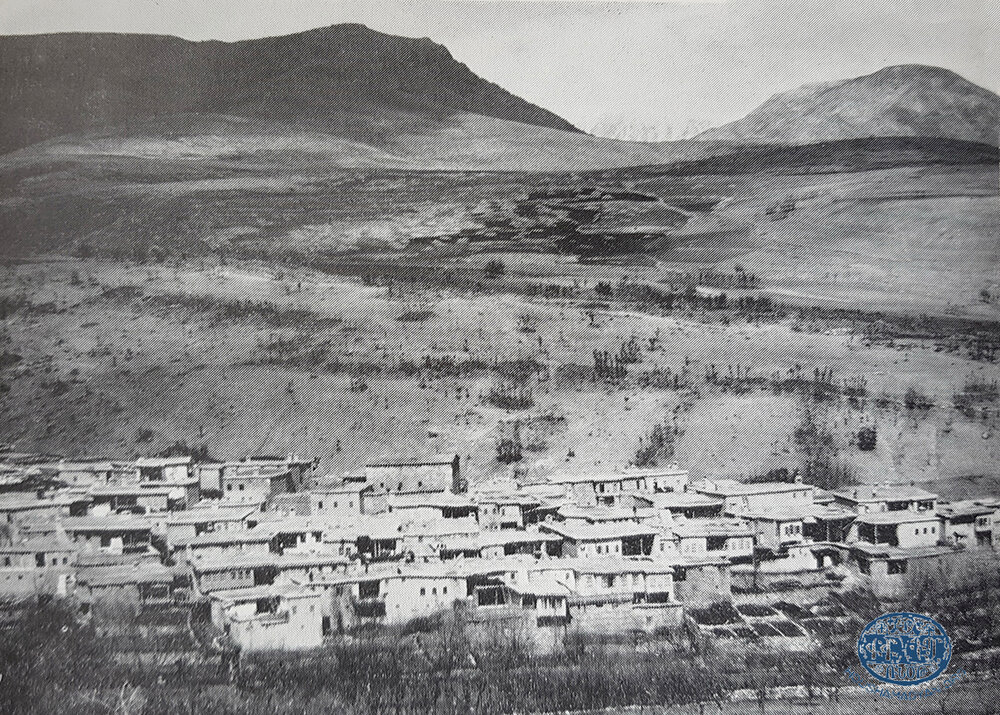

A view of Dzak (Source: Antranig Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, New York, 1969).

Dzak Pilgrimage Sites

• The genealogy of the Dzak village name is linked to one of it pilgrimage sites. In the direction of Karpoul, near the Bekerteh Bridge, there is a large, three-meter-long square cliff with a large hole. The locals call it Dzag, Dzag Kar or Trchouni Kar (Hole, Hole Rock, Bird Rock). Pakhdigian thus assumes that the village got its name from that of the pilgrimage site. Those suffering from whooping cough visited the site. Garlands of figs, walnuts, or rosewood would be hung from their necks to halt the cough. Poladian rejects the genealogy proposed by Pakhdigian and says that Dzak is a shorter version of the Armenian arevadzak (sunrise) since the early morning light was multi-colored, painting the mountains in different hues. [73]

• St. Kozmondianos: This site was basically for the healing the paralyzed and blind. Every year, in the spring, the villagers would travel her in groups. On the western side of the village, at the end of the eastern gorge, at the foot of the waterfall, there was a high hill where the Kozmondianos cemetery was located. The pilgrims lit candles near the grave, prayed, and the boys sang church songs and lit incense. [74]

• The pilgrimage site called Hermit Maghara was located in the southern part of the village, above the Shungol Valley, on a slope descending to Karpoul. It was a cave with masterfully carved walls with a circular arched cavity in the lower portion. There was a magnificent pool in the center. Drop by drop, the water fell from the arch filling the pool. According to tradition, the cave was built by a hermit as a place to live. [75].

• The St. Sarkis pilgrimage site was located near Dzak, on the banks of a river, atop a promontory. It had been a fortress and its ruins were still to be seen. [76].

Dzak Clergymen

Baghdasar Der-Mardirosian, a Protestant pastor, served the Protestant community of Harput/Kharpert for many years. During the era of the Ottoman Constitution, he returned to Dzak and resettled there. [77]

Grani/Öğrendik Village

Church of St. Garabed Church

The Armenian-populated village of Grani, surrounded by trees, was five hours walking distance to the east from Arapgir. [78]

It had a church, St. Garabed, built with the funds raised by a woman called Yeva. In the 1870s, Mrs. Yeva (Yeva of Grani) went to Constantinople to collect funds. She returned to the village and launched the construction of the church. [79].

S. Amadian notes that although Grani had a small church and school, the church was closed and there was no priest. [80]

Hatsgni (Hasgni) Village

Hatsgni was located at the foot of Mt. Gharadagh. [81]

St. Kevork Church

The church did not have a priest, and the spiritual needs of the people were served by random visiting clergy. According to Drtad Balian, the ruined church was a pilgrimage site since the beginning of the 20th century. Ancient artifacts were unearthed on the site over the years and a town once stood there. [82] An ancient site was discovered in the vicinity of that vineyard, and it was an old city on its site. Balian writes that ancient ruins were to be found in the vicinity of Hatsgni and that they were mentioned as late as 1905. Here are the names of those ruined monasteries.

Sourpiyan Monastery

It is also remembered as St. Yohan and was built in a valley.

Bolenag Monastery

It was also called Karasoun Mangounk (Forty Martyrs) Monastery.

Monastery of Khonrgdour

It was a large, renowned monastery in its day. During Balian’s time only the pulpit remained.

St. Toros Monastery

Also called St. Theodoros Monastery.

St. Yeghia Monastery

Located on a hillock.

There were other monasteries in Hatsgni whose names were not known to Balian [83]. S. Amadian notes that Hatsgni village had no priest. [84].

Khoroch/Yazmakaya Village

Khoroch (cavity/hollow) got its name because of its geographical position. It was located in a concave depression surrounded by four mountains. [85]

St. Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God Church)

The village had a church, St. Asdvadzadzin, which is mentioned in Hovhannes Matigian’s work “Mushegh and Galenigeh”. [86]

“Though they have a church, the jewel of the village, it too, like the people, has been in bad shape people. Most of its life, it has been widowed. That’s to say, without a priest." [87]

S. Amadian notes that Khoroch had no priest. [88]

Mashgerd/Çakırtaş Village

Mashgerd was located on the banks of the Euphrates River, on a slope. [89]

St. Sarkis Church

The church was located a bit further from the fortress of the village. It stood on a rock outcrop some 35-50 steps from the Euphrates. It was built with sand and large polished stones. The door of the church was so low and narrow that the four-year-old boy could barely walk through upright. The church's windows, opened recesses in the stones, measured 10 to 15 centimeters wide and 25 to 30 centimeters in height. Because of the darkness, it was hard to read in the church during the daytime. The walls were as wide as the walls of a fortress rampart, and the ceiling and the roof were thicker than two hundred centimeters. The interior of the church was interesting. The stairs, starting at the entrance of the church, divided into two parts. The first led to the main altar, and the second, to a separate church that had an inscribed stone altar. According to the inscription, it had been a church for two peoples (Armenians and Greeks) sharing the same religion.

According to tradition, the church was built by twins, a sister and brother, as their burial place. Hovhannes Matigian writes that their gravestones, with their huge covers, were visible from the main altar in the middle of the church.

It is likely that St. Sarkis was the church of Mashgerd, since the village of Mashgerd was founded on a cliff rising to the Euphrates. Later, due to the Euphrates' floods and the consequent losses of life, the population of Mashgerd relocated and founded the new village of Mashgerd and the church preserved as a pilgrimage or as a testament to the old town. The church's exterior was adorned with many crosses. There was an inscription on the building in which the date of construction was probably mentioned, but in the course of time the record became illegible. It is assumed that the church was a 1,500-year-old building [90].

Mashgerd’s old St. Sarkis Monastery was destroyed in an earthquake, and the new one was still standing in Pakhdigian’s day and shepherds brought their flock to graze in the vicinity of the church. St. Sarkis survived largely due to its solid structure and thanks to the kizilbash Kurds for whom St. Sarkis was as sacred as Ali. That is the Kurds, in the winter when the mountains and the fields were covered with snow, cleared the road leading to the church shoulder to shoulder with Mashgerd residents. [91]

The Vartabed Spring was located to the south of the St. Sarkis Church. It’s assumed that one of the church’s priests organized the building of the spring. [92]

Fruit from the mulberry trees growing in front of the church and revenue from the church’s lands were allocated to the poor. [93]

The cemetery of Old Mashgerd was located opposite the church. It contained the graves of priests and bishops. [94]

St. Asdvadzadzin Church

There is no information about this church, which Poladian says was located in Mashgerd [95].

It is mentioned that Mashgerd had a new church, a school and two priests. The reference is probably about St. Asdvadzadzin. [96]

For a time, when Mashgerd had no teacher, it was the village priest who instructed the cleverer of the boys. [97].

Mashgerd’s Protestant Church

Poladian mentions that when missionaries entered Arapgir to 1853, a Protestant church was built in Mashgerd. [98]

It was basically due to the Protestant missionaries that an adequate level of education in Mashgerd, Anchrti and Dzak was maintained. [99].

Mashgerd Village Pilgrimage Sites

- In the south-eastern part of the village of Mashgerd, when entering the village, there was a tree-lined spring, decorated with ten pools carved in the stone. The locals called this place the Verin Aghpyur (Upper Spring). Patients afflicted with malaria and related ailments would come to “take the water” and be cured. The waters of the Upper Spring were highly praised. There were giant mulberry trees near the spring. Village shepherds would usually gather their flocks near the spring at midday. [100]

- The divine liturgy was sometimes celebrated at the open-air holy site of St. Aharon, located in the southern part of the village. There was a gum elemi tree near the site and those beseeching St. Aharon for medical treatment would tie pieces of cloth on its branches. [101]

Mashgerd Village Clergy

- Father Avedis Der-Avedisian: The Der-Avedisian clan of Mashgerd gave seven priests to the Armenian nation. The last of them, Father Avedis, made a great contribution to the construction of the local Church (St. Sarkis Church or Holy Mother of God Church) and was buried in the church vestibule. [102].

- Very Rev. Mardiros Siraganian (see biography in Clergymen of Arapgir section).

Saghmga Village

St. Asdvadzadzin Church (Holy Mother of God)

According to Poladian, the vestibule of this small stone church served as a school. [103]

The newly built church had a safe house/refuge for orphans or neglected children, a priest, and a teacher. [104]

Vank/Salkımlı Village

The village of Vank was located on the banks of the Chay River of Agn. [105]

The village had a ruined church, whose name is not mentioned in the sources. A four-story castle existed above the church. In the day, one could see an altar carved into the wall of the fort’s first floor. Steps, carved in the rocks, leading to the second floor were in front of the altar. [106]

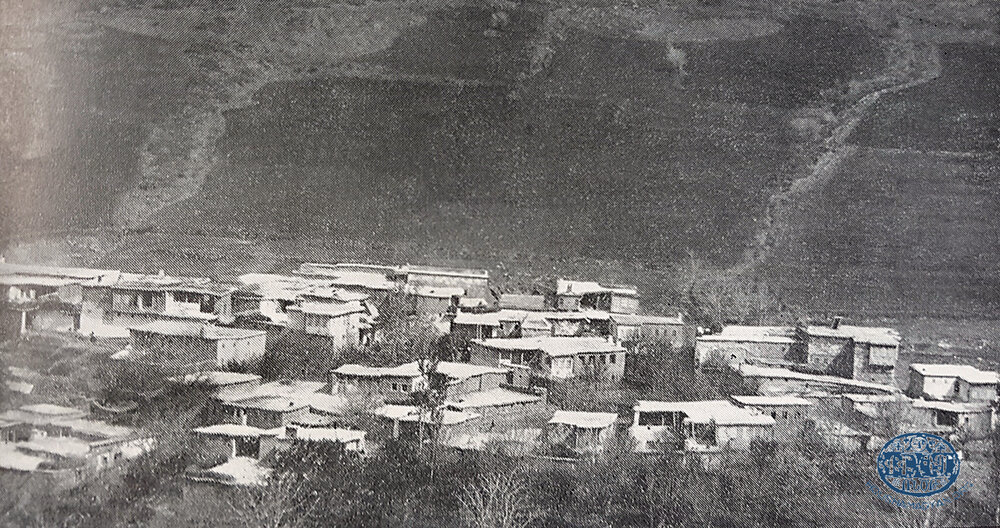

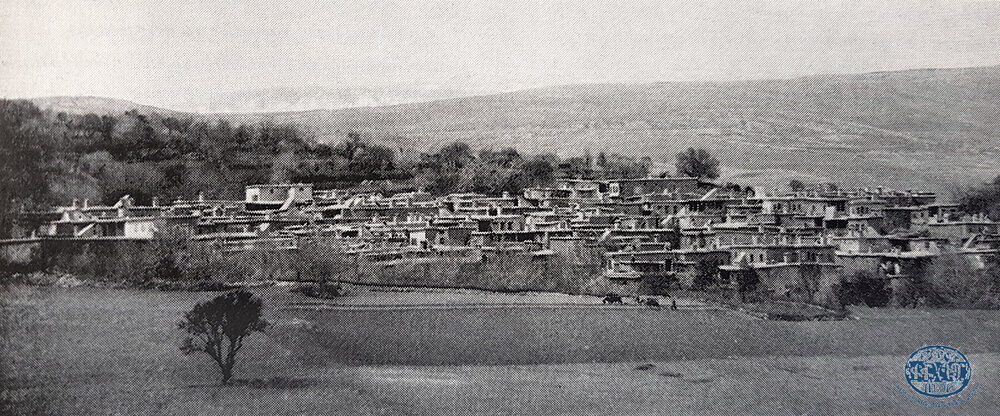

Vank/Salkımlı Village (Source: Antranig Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, New York, 1969).

Koushna/Küşne Village

St. Asdvadzadzin Pilgrimage Site (Holy Mother of God)

The village of Koushna was located five hours away, on foot, from Arapgir. [107]

It had a church called St. Asdvadzadzin. The monastery was in ruins and served as a pilgrimage site and is mentioned in an article by Mardiros Pehlivanian.The site was located on a mountain and people usually travelled there on Saturdays. The pilgrimage lasted for one week. Residents of almost all the Armenian-populated villages of the Arapgir district visited the site, prayed, talked about their ailments, and asked for healing. Here’s a song that was sung at the site. [108]

Come God, to hear our petitions,

You are the refuge from irritants,

Come to the aid of your servants,

Be of assistance to the Armenian nation. [109]

S. Amadian notes that the church in Koushna did not have a priest. [110]

Vaghashen/Vaghshen/Bahadırlar Village

St. Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God Church)

This church was located outside the village. [111] There were mounds of dirt adjacent to the church where unbaptized children were buried. To get to the church, one had to descend twelve steps. On the left side of the church entrance there was a bubbling spring, the sound of which was a cure for earaches. [112] The church did not have a bell tower. In 1907, Vaghashen residents decided to build a bell tower, but they encountered a government ban, even though the bell had already been forged in Edirne and had been inscribed with the donors’ names.

Drtad Balian notes that the Vaghashen Monastery was located seven kilometers from Arapgir and twelve hours from Agn. It was under the rule of the Arapgir diocese. Vaghashen’s Holy Mother of God Church was still standing in 1905. It had been rebuilt in 1834. According to Balian, there was a monastery near the church, but it had fallen into disuse and ruin long ago. [113]

S. Amadian notes that the Vaghashen church had no priest. [114]

Church of Beleneg

The Beleneg Church was located one hour to the east of Vaghashen, on the banks of the Euphrates. On the four sides of that church, even on the road to the village, one could see traces of old houses and the outlines of seven ruined churches. There was a small cave/fortress with rooms below the church that the locals called (Stone Rooms). Not far from the fortress, on the banks of the Euphrates, were two standing forts. All these traces prove that Vaghashen was once a large settlement. [115]

Clergymen of Vaghashen Village

Father Levon Nigoghosian (secular name, Krikor Nigoghosian). In 1911, at the request of many Vaghashen Armenians, Nigoghosian was ordained a priest in Diyarbekir by Archbishop Zaven Yeghiayan. He then returned to Vaghashen and served his forty days of penitence the school adjacent to the church. Father Levon celebrated his first mass on the Sunday of the Apparition of the Holy Cross, in the presence of Father Tornig, Father Goriun, and Father Parsegh Poghharian from Anchrti. [116]

Anchrti/Topkapı Village

The village of Anchrti was located between the towns of Arapgir and Agn; 9-10 miles south of Agn and the same distance east of Arapgir. [117]

St. Nshan Church

St. Nshan is mentioned in the work "The Activities of the Criminals of Anchrti and the Surrounding Villages”, which points out that Anchrti, with its magnificent church and two school, was the object of the admiration of the nearby villages and towns. [118] According to Poladian, the best priests were found in Anchrti. [119]

Anchrti Village Clergymen

- Father Garabed: Was the village priest before the Hamidian Massacres He was killed along the banks of the Euphrates during these massacres. Father Garabed’s son, Arakel Aghpar, sang in the choir, served on the altar, worked as a sexton and a teacher. [120]

- Father Harutiun Pogharian: Served as Anchrti pastor. [121]

- Father Garabed Derderyants: Served as Anchrti pastor. [122]

Vaghaver/Ağın Village

Vaghaver was a rural town half populated by Armenians located on the banks of the Chai River of Agn, in the valley, surrounded by high mountains stretching toward the Euphrates. [123]

Historically, the village is referred to as Djermag Dzak, but the locals called it Vaghaver, Aghn was the village’s the Turkish name. [124]

Vaghaver did not have a priest, but had one spiritual official, endowed with the authority of a Protestant pastor and an Apostolic priest. This person preached, baptized, and performed village burials at the Protestant and Apostolic community cemeteries. [125]

St. Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God Church)

Vaghaver had a church called St. Asdvadzadzin and one priest. [126]

Protestant Church

In addition to St. Asdvadzadzin, there was also a Protestant church in Vaghaver. In the 1860s, when American missionaries started to enter the provinces, building schools and churches, Vaghaver also fell under their influence. [127]

Most of the Vaghaver’s Armenian residents were Protestants. Poladian notes that, initially, the Protestants would work hard during the day to build their church and the Apostolic Armenians would tear it down during the night. The local authorities seemed to welcome “the acts of bravery” on both sides. Finally, the Protestants abandoned their church site in the center of the village and moved to the outskirts where they built an expansive three -tory church, with a parish house and school. During the years preceding 1915, however, both the Apostolic church and the school ceased functioning since the six or seven families left in the village couldn’t afford to pay for a priest or teacher. [128]

Prayers in the Protestant church began with the hymn Aravod Louso (Morning Light) and those of Nerses Shnorhali. On Sundays, as a rule, Apostolic churchgoers would also visit the Protestant church. And on Easter, when a priest visited the village, the faithful of both communities filled the church to attend the liturgy and hear the sermon. [129]

Clergymen of Vaghaver Village

- Aram Siraganian: Native of Arapgir. Graduated from the Euphrates College in 1909. Served as Protestant pastor of Vaghaver and Hayni villages. He was killed during 1915 Genocide. [130]

- Protestant Pastor Armenag Siraganian (see biography in the Shepig village clergy section).

Ehnetsik/Salkımlı Village

St. Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God Church)

At one time, the Arapgir district received refugees from Ani, and some settled in this village. According to Poladian, the fact that the name Ehnetsik is derived from Anetsik (people of Ani) bears this out. [131]

No information about the St. Asdvadzadzin has survived. [132]

S. Amadian notes that Ehnetsik had no priest. [133]

Protestant Church

The Protestant church in the village was built with the help of locals and missionaries, by the Pastor Melkon Minasian, from Shepig, with the help of local Armenians and American missionaries. Minasian hadn’t yet been ordained a Protestant pastor when the church was built. [134].

Dzablvar Village

Dzablvar was also an Armenian-populated village in Arapgir. Unfortunately, Poladian, Srvantsdiants, Pakhdigian and others do not mention anything about the village’s churches or pilgrimage sites. [135]

- [1] Sarkis Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, Brief Historical-Ethnographic View, Beirut, 1934, p. 123. [in Armenian]

- [2] Ibid, page 17.

- [3] Pounch, September 2, 1869. [in Armenian]

- [4] Antranig Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, New York, 1969, pp. 495-496. [in Armenian]

- [5] Pasmaveb, 1953, July-August, pp. 186.

- [6] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p.18 [in Armenian]

- [7] Ibid.

- [8] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, page 494. [in Armenian]

- [9] Arevelk Daily, May 26, 1893 [in Armenian]

- [10] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 494-495. [in Armenian]

- [11] Maghakia Ormanian, Azkabadoum, Volume 3, Beirut, 1961, p. 51. [in Armenian]

- [12] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 495-496. [in Armenian]

- [13] Ibid, pp. 496.

- [14] Ibid, pages 25-27p

- [15] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 27. [in Armenian]

- [16] Ibid.

- [17] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 497. [in Armenian]

- [18] Ibid, pp. 497-498.

- [19] Ibid, pp. 492-493.

- [20] Ibid, pp. 498.

- [21] Ibid.

- [22] Ibid, page 499.

- [23] Ibid.

- [24] New Arapgir Directory, 1958, No. 51, pp. 1880-1881. [in Armenian]

- [25] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, page 489. [in Armenian]

- [26] Ibid, pp. 502.

- [27] No, page 510.

- [28] New Arapgir Directory, 1958, No. 51, pages 948-950. [in Armenian]

- [29] Ghougas Indjidjian, Geography, A, Venice, 1806, p. 306. [in Armenian]

- [30] S. Eprigian, Natural World Dictionary, Venice, 1902, p. 81. [in Armenian]

- [31] Pyuzantion, 1905, No. 2806. [in Armenian]

- [32] Arevelyan Mamoul, 1907, No. 21, pp. 518. [in Armenian]

- [33] Hamazasb Vosgian, The Monasteries of Sepasdia, Kharpert, Diyarbekir and Trabzon, Vienna, 1962, p. 74. [In Armenian]

- [34] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. Oriental Press, Feb. 1885, #2 [in Armenian]

- [35] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, page 17. [in Armenian]

- [36] Avedaper, Constantinople, 1903, No. 14, pp. 248-250. [in Armenian]

- [37] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 201. [in Armenian]

- [38] Ibid.

- [39] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p.38. [in Armenian]

- [40] Ardashes Kardashian, Material for the Armenian History of Egypt, Cairo, 1943, pp. 205-206. [in Armenian]

- [41] Poladian, History of the Armenian Arapgir, p. 488. [in Armenian]

- [42] Sarkis Pakhdigian, Vosgekedag, Volume 3, 1948, pp. 146-147. [in Armenian]

- [43] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, page 525. [in Armenian]

- [44] Ibid.

- [45] Avedaper, Constantinople, 1903, No. 6, p. 107. [in Armenian]

- [46] Ibid.

- [47] Ibid.

- [48] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 128. [in Armenian]

- [49] Ibid.

- [50] Ibid.

- [51] Ibid, p.

- [52] Ibid.

- [53] Ibid.

- [54] Ibid.

- [55] Ibid, p.130.

- [56] Pakhdigian, Vosgekedag, First Volume, 1945, p. 170. [in Armenian]

- [57] Avedaper, Constantinople, 1903, No. 6, p. 107. [in Armenian]

- [58] Missionary Herald,1858, pp. 168-164; Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 106. [in Armenian]

- [59] Ibid.

- [60] Ibid, p.107.

- [61] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 130. [in Armenian]

- [62] Ibid, pp. 130-133.

- [63] Ibid, p. 133.

- [64] Masis, Jan. 28, 1898, No. 351. [in Armenian]

- [65] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 500. [in Armenian]

- [66] Ibid, page 107.

- [67] Memoir of Euphrates College, pages 47, 49, 59, 60. [in Armenian]

- [68] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 134. [in Armenian]

- [69] Ibid, page 114.

- [70] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 134. [in Armenian]

- [71] Ibid.

- [72] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, page 111. [in Armenian]

- [73] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 134. [in Armenian]

- [74] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 113. [in Armenian]

- [75] Ibid.

- [76] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 135-136. [in Armenian]

- [77] Pakhdigian, Vosgekedag, page 191. [in Armenian]

- [78] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 136. [in Armenian]

- [79] Ibid.

- [80] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, p. 112. [in Armenian]

- [81] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 138. [in Armenia]

- [82] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 134. [in Armenian]

- [83] Ibid, p. 502.

- [84] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, p. 112. [in Armenian]

- [85] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 138. [in Armenian]

- [86] Soukias Efrigian, Natural World Dictionary, Volume 2, Venice, 1902, p. 195. [in Armenian]

- [87] Hovhannes Matigian, Moushegh and Galenigeh, p. 113-119. [in Armenian]

- [88] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, page 112. [in Armenian]

- [89] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 140. {in Armenian]

- [90] Matigian, pp. 113-119.

- [91] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 146. [in Armenian]

- [92] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 117. [in Armenian]

- [93] Ibid, pages 117-118.

- [94] Ibid, p. 117.

- [95] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 146. [in Armenian]

- [96] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, page 111. [in Armenian]

- [97] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, page 183. [in Armenian]

- [98] Ibid, pp. 522.

- [99] Ibid, p. 120.

- [100] Ibid, p. 140.

- [101] Ibid, p. 117.

- [102] Ibid, p. 754.

- [103] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 147. [in Armenian]

- [104] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, p. 110. [in Armenian]

- [105] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 147. [in Armenian]

- [106] Ibid, pages 147-148.

- [107] Ibid, p. 149.

- [108] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 502. [in Armenian]

- [109] Rev. Fr. Mgrdich Bodourian, Armenian Encyclopedia, p. 235, Bucharest, 1938. [in Armenian]

- [110] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, page 112. [in Armenian]

- [111] Pakhdigian, Vosgekedag, page 205. [in Armenian]

- [112] Ibid.

- [113] A New List from Van, B, Arapgir and Agn Monasteries", Pyuzantion, 10th year., Nov. 29-Dec. 12, No. 2806. [in Armenian]

- [114] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, page 112. [in Armenian]

- [115] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, page 150. [in Armenian]

- [116] Pakhdigian, Vosgekedag, page 207. [in Armenian]

- [117] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, page 83. [in Armenian]

- [118] The Activities of the Criminals of Anchrti and the Surrounding Villages, 1915-1918, Boston, page 52. [in Armenian]

- [119] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 89 [in Armenian]

- [120] Ibid, page 91.

- [121] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, p. 109. [in Armenian]

- [122] Ibid.

- [123] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 152. [in Armenian]

- [124] Ibid, p. 153.

- [125] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 99. [in Armenian]

- [126] Arevelyan Mamoul, March 1885, p. 112. [in Armenian]

- [127] Pakhdigian, Arapgir and Surrounding Villages, p. 153. [in Armenian]

- [128] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 98. [in Armenian]

- [129] Ibid.

- [130] Ibid, p. 525.

- [131] Ibid, p. 84.

- [132] Eprigian, Natural World Dictionary, p. 807. [in Armenian]

- [133] Arevelyan Mamoul,, March 1885, page 112. [in Armenian]

- [134] Avedaper, Constantinople, 1903, No. 6, p. 107. [in Armenian]

- [135] Poladian, History of Armenian Arapgir, p. 82. [in Armenian]