Ayntab - Commerce

Author: Ani Voskanyan, 02/12/2023 (Last modified: 02/12/2023) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

In the second half of the 19th century, Ayntab ranked second only to the city of Aleppo in terms of commercial activity in the province of Aleppo. Most of Ayntab’s trade was conducted with the city of Aleppo. By the early 20th century, merchants from Ayntab were signing large business contracts with traders from many other cities and constantly creating new trade routes. According to the Pyuragn weekly periodical, Ayntab had direct commercial ties with Smyrna, Beirut, and Constantinople. [1]

In the early 20th century, Ayntab was home to 87 Armenian merchants, 57 of whom operated their businesses from the city’s khans [2], while 30 owned their own stores or premises. Among these merchants were wholesale traders of clothing, woven textile, leather, coffee, sugar, metals, cotton, oil, soap, pharmaceuticals, and rugs. [3]

An article published in a 1908 issue of Pyuragn provides valuable information regarding the prices of various imports, exports, and products in the markets of Ayntab. According to this article, in 1908, 20 bales of wool were exported from Ayntab to Damascus. The price ranged from five to five-and-a-half kurus per okha (one okha = 1,282 kilograms). The article mentions that at this time, the price of wool had fallen, as it had everywhere else in the world, due to decreased demand in Europe. The price of cotton ranged from six to six-and-a-half kurus. Cotton was in very high demand. Almonds, depending on the season and the demand, ranged from 13 to 14.5 kurus per okha. Pistachios were sold at 18-18.25 kurus per okha. If the crop was damaged or if the market was saturated, the price would fall to 13-13.5 kurus per okha. Kitre (wild herbs) were sold for 5.75-6 kurus. The price of djehri (buckthorn) had fallen significantly to 3-3.25 kurus. In 1907, oil was sold for 17-17.25 kurus; and in 1908 for 13.5-13 4/5 kurus. Sugar was priced at 3 5/8 kurus, and corn at three kurus. The residents of Ayntab consumed 550,000-600,000 goat hides per year. In 1907, one okha of clean goat hide was priced at 21 kurus, but by 1908, the price had fallen to 17-17.75 kurus. [4]

The Araks periodical of Saint Petersburg also wrote about the products and crops produced in Cilicia in the late 19th century, with special emphasis on the pistachios grown in Ayntab. As the periodical notes, Ayntab pistachios were known by the name of “Sham fusdukh,” and were exported in large quantities to Europe. [5] Pyuragn also mentions Ayntab pistachios, listing the amounts produced in Ayntab and nearby villages. [6]

The mountainous area separating Ayntab from Roum Kale (Hromgla) was entirely planted with pistachio trees. This area produced nine-tenths of the pistachios exported from the Ottoman Empire each year, yielding a yearly income of 150,000 pounds. One-quarter of this land belonged to Armenians, with about an equal percentage owned respectively by Kurds, Yezidis, and Turks. Most land in the actual Ayntab valley belonged to Armenians. [7]

The principal imports of Ayntab were coffee, sugar, petrol, metals, copper, pewter, glass, and silk. Cotton yarn of all colors, especially white and red, was in great demand and was imported in large quantities to be used for weaving. [8]

Notably, in 1906, a branch of the central Ottoman Bank was opened in Ayntab, which, as reported by Pyuragn, contributed to the further growth of commerce in the city. [9] The same publication informs us that in 1907, the director of the Ayntab branch of the Ottoman Bank was Mihran Puzantian. [10]

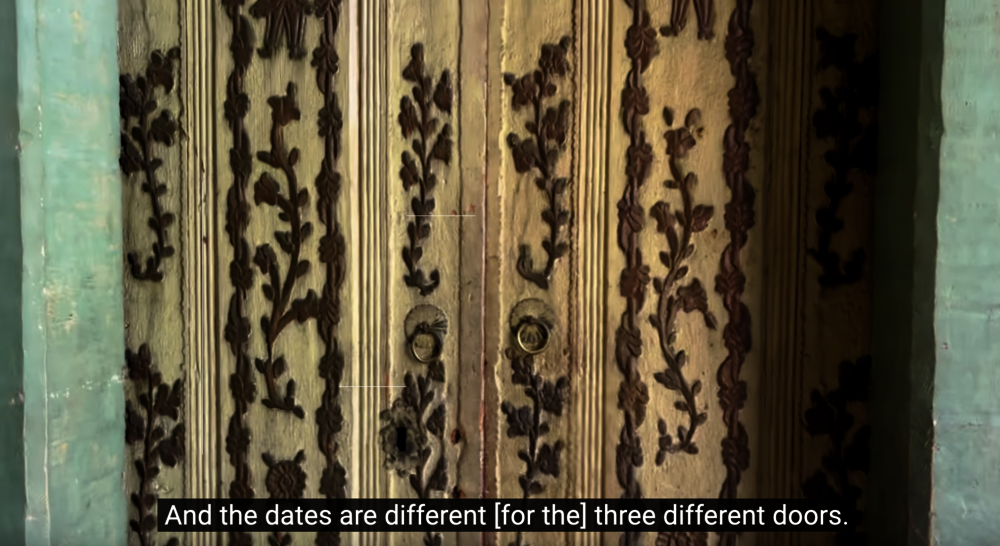

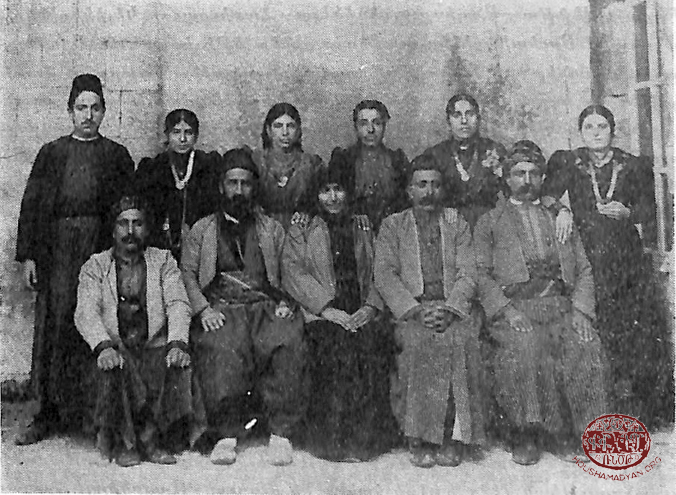

This video, filmed by Azad Balabanian, features the former mansion of the Nazaretian family, one of the prominent Armenian merchant families of Ayntab. Today, the mansion houses a coffee shop. In the video, Murad Uçaner, an Ayntab historian, provides historical information on the family and the mansion.

Prominent Companies, Merchant Families, and Individual Merchants

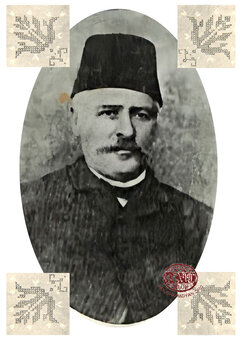

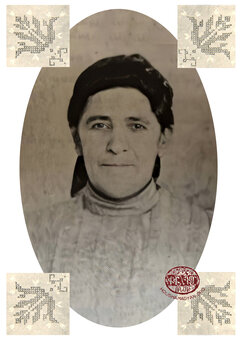

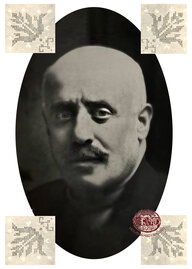

The Nazaretian Family

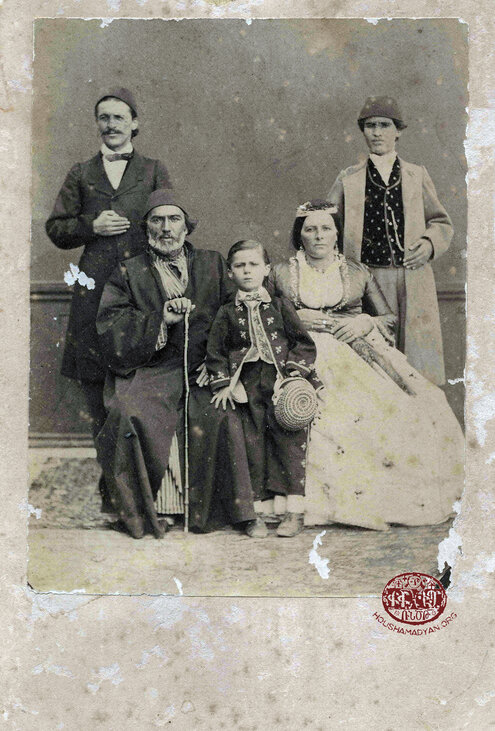

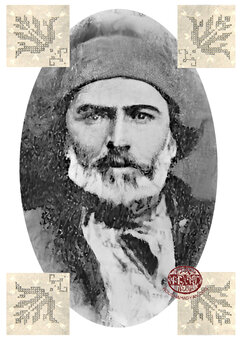

The Nazaretians were among the families that personified the history of Ayntab Armenians the 19th century. Nazar Agha Nazaretian (1815-1887) was the Persian consul in Ayntab. He was an expert jeweler and a major merchant. He was considered the richest man in Ayntab in the 19th century. In the city, he was better known by the name of Kara Nazar (Black Nazar). Nigoghos Nazaretian (1843-1899) was Kara Nazar’s son and would later become a renowned merchant in his own right. He founded the Nazar Agha Grand Khan, named after his father, located next to the Nazaretians’ masbana (soap factory). [11]

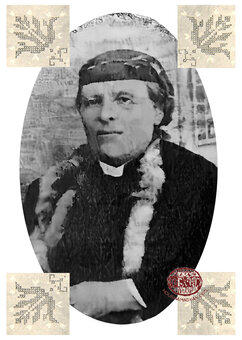

Nigoghos Agha Nazaretian was educated by clerics and special tutors called khalfes. He had studied Turkish, French, and some Latin. Through reading and self-education, and by learning from those he met, he had also acquired skills in jurisprudence and administration. “He was an enlightened man, a friend and counselor of other enlightened people,” as stated by Hovhannes Agha Kurkdjianof, head of the Ayntab customs office from 1866 to 1883, and a highly educated man. [12] In 1863, after the ratification of the National Constitution, the first Armenian neighborhood council in the city of Ayntab was elected thanks to the efforts of Nigoghos Nazaretian and his associates, including Kevork Sulahian, Hagopdjan Yaghoubian, Hagop Arakelian, Avedis Miridjanian, Hovhannes Lousararian, Nerses Baluyan, Khachadour Bogharian, Avedis Parseghian, Hanne Tahtadjian, Kalousd Ghazarian, and others. The neighborhood council oversaw community life in the Armenian neighborhood of the city. For at least five terms, Nigoghos Nazaretian served as the chairman of this important community body, achieving great successes in this role. [13] Neighborhood councils were not public agencies, rather, they were community organizations. They had three to nine members, depending on the neighborhood. These councils’ primary duty was to oversee national/community life within each neighborhood. Each council was elected by the residents of the applicable neighborhood for a term of two years. [14] The councils answered to their diocesan provincial councils. Within each neighborhood, all church and parochial school properties were under the care of the neighborhood council. [15] Nazaretian’s service on the Ayntab neighborhood council spanned about 20 years. He was also elected as a member of the local autonomous leadership, or the Mejlis Idare. He participated in meetings of the provincial council. [16]

Nigoghos Agha Nazaretian’s name became enshrined in Ayntab history as an organizer and participant of countless community projects or initiatives. Notable among these was the Vartanants Museum Company, which founded the Vartanian Institute (active from 1882 to 1915). The construction of the institute’s own building was funded by Kalousd Agha Nazarian. The Vartanants Museum Company also oversaw and improved the parochial Nersesian School, for which, upon the request of the neighborhood council, it invited teachers from Constantinople. Nigoghos Agha was also the principal adviser of the team that founded the Cilician boarding school (1870-1877), and an ardent supporter of the project; as well as the primary supporter of the founding of the Hayganoushian School for girls. [17] It was thanks to his efforts and financial contributions that the famous Holy Mother-of-God Church of Ayntab was built [18] (designed by the court architect, Sarkis Bey Balian). The cost of the construction of the church was 10,000 Ottoman pounds. [19]

Deacon Hovsep Ashdjian, a native of Ayntab and a member of the Armenian monastic order in Jerusalem, funded the construction of the new prelacy building in Ayntab. After his death, thanks to the efforts of Nigoghos Agha Nazaretian, the deacon’s estate was dedicated to the construction of Millet Khan (National Home) in 1868. The building was registered in government records under the name of Azizie Khan (at the suggestion of Nigoghos Agha, it was formally named after the ruling Ottoman sovereign, Sultan Abdul-Aziz). This khan, considered modern for its time, was considered one of the most profitable Armenian national establishments. Until 1915, proceeds from the khan funded the uninterrupted operation of the Nersesian, Hayganoushian, and Haygazian schools. [20]

Thanks to the estate of Deacon Hovsep Ashdjian and the efforts of Nigoghos Nazaretian, the parochial Nersesian School and a coffee house adjacent to Millet Khan were also built. [21] Nigoghos Agha’s foresight allowed the Armenian community of Ayntab to own such establishments as Millet Khan and Chokour Bostani Deylib [22]. It was also thanks to Nigoghos Nazaretian that in 1873-1874, alongside the construction of a new church, a “profitable property” was built on the land located in front of the old church, housing 14 stores. [23]

In addition to establishing and supporting institutions that ensured the advancement of the Armenians of Ayntab and the development of the Armenian educational system in the city, Nazaretian also encouraged and supported gifted youths who traveled to Etchmiadzin, Jerusalem, and elsewhere to study, so that upon their return, they could contribute to national/educational advancement and progress in Ayntab. [24]

Kara Nazar’s youngest son, Garabed Bey Nazaretian, served as the Persian consul in Ayntab after his father. [25] He was a well-known merchant, owned a soap factory, and generously donated to community/national initiatives. [26]

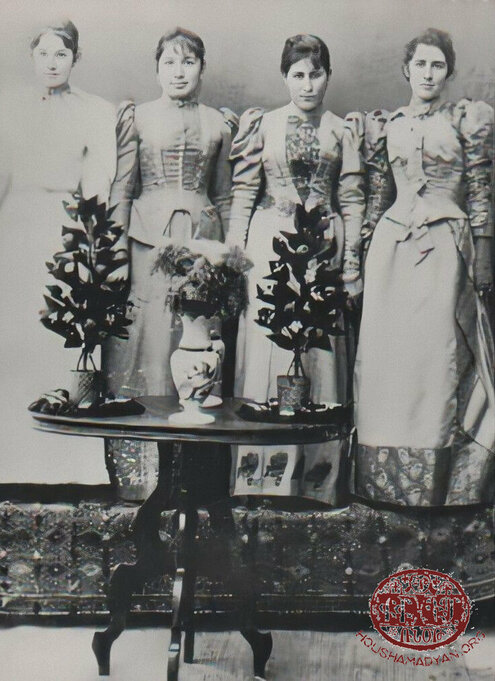

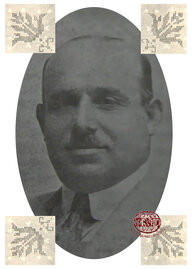

The Manoushagian Family

Nazaret Manoushagian was Nazar Nazaretian’s grandson, son of Mennoush Nazaretian. In 1890, after graduating from the Vartanian Institute, he founded the N. Manoushagian and Associates firm with his friends. After the massacres of 1895, like many families involved in the intellectual and commercial fields, Manoushagian and his family fled Ayntab and spent four years in Cyprus. Once the political situation had changed, they returned to Ayntab, where Nazaret re-established his firm and, partnering principally with the Khachadourian brothers, became involved in the importation of dye. For many years, he served as a member of the provincial council of Ayntab, as chairman of the political committee and educational council, and on the boards of trustees of the Vartanian and Hayganoushian schools. Nazaret Manoushagian was one of the founders of the first Armenian kindergarten in Ayntab, the Vartanian kindergarten (1899). He was a member of the trade court of Ayntab, as well as the city’s Akhzu Asker Comision (military commission). In 1911, on a trip to Ayntab from Egypt, Haroutyun Djebedjian founded the Ayntab chapter of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU). Nazaret Manoushagian was elected secretary of the chapter’s executive committee, with Dr. Hovsep Bezdjian serving as chairman and Kalousd Agha Ghazarian as deputy chairman. In April 1915, three months before the start of the deportations in Ayntab, Nazaret Manoushagian was arrested alongside other intellectuals and businessmen and detained in the prison of Aleppo. Although he was released and returned to Ayntab, he was not spared from the ensuing deportations and plunder. [27]

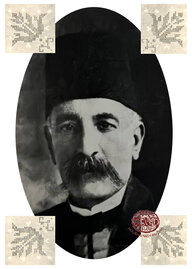

The Ghazarian and Sahagian Families

Kalousd Ghazarian was another one of Ayntab’s notable Armenian community leaders. He had friendly, as well as business relations with the Nazaretian family. [28] Kalousd Ghazarian began his career with Sarkis Sahagian as an exporter/importer of fruits, vegetables, and grains. After settling in Ayntab, the two men began working in Nazar Khan and became involved in the manisa trade. They would export Ayntab manisa to Tokat, and from there they would import yazma (a special type of fabric used to make women’s headscarves). Kalousd Ghazarian and Sarkis Sahagian also founded a bank, located near the saray (government hall), the central market, and the badastens (bezzazistan/petesten, a market for fabric traders and other merchants). The bank was almost adjacent to Garabed Bey Nazaretian’s masbana (soap factory). [29] Of the funds needed for the construction of this Banka Khan, Sarkis Sahagian provided 60 percent, and Kalousd Ghazarian 40 percent. Banka Khan, aside from hosting commercial establishments, also engaged in banking activities. In a short time, after making several profitable investments, it became a true banking establishment.

Sarkis Sahagian and Kalousd Ghazarian owned magnificent houses in Ayntab, described as “palaces.” The former lived in the Kayadjuk neighborhood, and the latter in the Church neighborhood, on the road to Kouzanli and Kastel Pashi, near the Vartanian Institute. [30]

Kalousd Ghazarian was also known for his philanthropy. Thanks to him, many community buildings were renovated, and many new ones built. The Araks monthly periodical of Saint Petersburg, writing about the “affluent Armenians” of Ayntab, emphasized Kalousd Ghazarian’s dedication to his community, specifically noting his contributions in the field of education. [31] Kalousd Ghazarian’s wife, Lucia Nazaretian-Ghazarian, was also actively involved in philanthropy: “Mrs. Lucia funded the construction of the new building of the Hayganoushian Girls’ School, as a gift to her people.” [32]

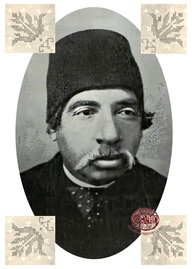

The Ashdjian Family

Bedros Ashdjian was another prominent merchant from Ayntab. He was the grandson of well-known philanthropist Deacon Hovsep Ashdjian. Initially, Bedros Ashdjian was active in the manufacturing business, but later, he became a pistachio trader. By using the method of grafting, he increased the yields of his crops and expanded his pistachio groves. After becoming the dominant player in the pistachio markets of Aleppo and Constantinople, Ashdjian began exporting pistachios as far afield as America. Ashdjian’s wealth was valued at 100,000 Ottoman pounds. His properties and estates included a palatial house, villages, farms, herds of sheep, and of course, vast groves of pistachio trees. Contemporaries described him as the “king of pistachios.”

Ashdjian was also known for his philanthropy. Specifically, he organized and led a fundraising committee that contributed a sum of 2,500 Ottoman pounds, as well as items valued at 7,500 Ottoman pounds, to the victims of the 1909 Adana massacres. Ashdjian died in poverty, in a rented home in the city of Alexandria. [33]

The Karamanougian Family

Garoudj Karamanougian (Chivan Garoudj) was one of the foremost merchants and landowners of Ayntab. According to official ledgers, Karamanougian’s wealth was valued at 45,000 Ottoman pounds, of which 15,000 was invested in profitable real estate. Among the properties he owned were stores in the city; as well as farms, orchards, and pistachio groves in the neighboring villages. Karamanougian had invested another 15,000 pounds in the field of embroidery. He employed 4,000 to 5,000 women to produce “Ayntab embroidery,” which was exported to the United States. To ensure that the product had a ready market in the States, Garoudj had previously sent his son, Movses Karamanougian, to the country. The remainder of Karamanougian’s wealth, another 15,000 pounds, was invested in the vast commercial center of manufactured goods that he owned on Soupourdji Boulevard. This establishment employed three clerks, 8-18 salespeople, as well as a general accountant/clerk who “balanced the books” (treasurer). [34]

Manoushag Karamanougian was married to Hovhannes Djebedjian [35], who was also active in the pistachio trade. Hovhannes purchased large tracts of land covered in wild pistachio (or fustukh) trees, then grafted them with the trees he already owned. Over time, he achieved great successes in business, becoming a pistachio exporter and the owner of vast properties.

The Sulahian Family

Hrand Sulahian became active in his family’s business beginning in the 1890s. Not satisfied with his success in the business field, he also made significant contributions to his community and political party. Between 1896 and 1910, he worked diligently as a member of the Ayntab Prelacy. He was an important participant in meetings at the Vartanian Institute and in Sunday lectures. Sulahian’s wife was the daughter of Garabed Nazaretian, a member of the prominent Nazaretian family. [36]

The organization known as the “Cooperative Company of Wealthy Armenians” of Ayntab dispatched Hrand Sulahian to Europe, so that he could learn the use of modern manufacturing equipment. After spending six months in Paris and London, he returned home, bringing with him mills and other modern machines. [37]

The Niziblian Family

Adour Agha Niziblian was a painter’s son, who grew up to be one of the most highly educated and wealthiest merchants in Ayntab. He dedicated his wealth to the advancement of his compatriots. Niziblian founded the Roupinian Society, which provided the community with a lecture hall, library/reading room, night classes, and theatrical performances. Adour Agha also contributed significantly to the advancement of both boys’ and girls’ education in Ayntab. [38] He died in 1893, bequeathing 750 Ottoman pounds ($3,300) to the pastor of the city’s Evangelical church, Professor Alexan Bezdjian, for two purposes: $1,100 was dedicated to supporting the theatrical, educational, and charity work of the Evangelical church of the Hayig neighborhood; and $2,200 was dedicated for the expansion of the land owned by the Christian Youth Organization. As a token of gratitude, this organization named its building after its benefactor, calling it the “Niziblian Museum.” Difficulties arose in the execution of Niziblian’s will, with some funds transferred to the United States, where the Adoor Agha Trust Fund was created. [39]

Niziblian began his career without any capital, relying on his proficiency in Turkish to open doors for him. He began working with Hagop Agha Misirian, and afterwards, after earning some money, entered into a partnership with Hagop Agha Kurkdjian. This partnership lasted 20 years (1861-1880). Niziblian’s most profitable business contract was signed in 1862, allowing him to import large amounts of fabric and yarn from the United States in the years 1862-1865.

In the second half of the 19th century, Adour Niziblian spent 8,000 pounds to build a new house in Ayntab, with an entirely unique floor plan and artistic additions. According to contemporaries, the house was comparable to a palace. [40]

The Baronian Family

Ayntab was a city of bountiful orchards and superior potable water, which allowed for the production of high-quality wine and spirits. This field was dominated by Armenians and was a widely practiced and lucrative occupation. The arak of Ayntab was exported and sold across the Ottoman Empire. Perhaps the best-known and most successful arak distiller from Ayntab was Nerses Baronian. The two largest distilleries in the city belonged to him and produced 800-1,000 “geluns” (gallons) of pure arak per day. In the winter, production fell to 200-300 “geluns” per day. Nerses Baronian also exported his product. He had a caravan of mules at his disposal, which transported his arak to various cities. The arak market of Gesaria was entirely in Baronian’s hands. Nerses Baronian did not remain indifferent to national issues and initiatives. He served for many years on the boards of trustees of the parochial Nersesian School and the Atenagan School. [41]

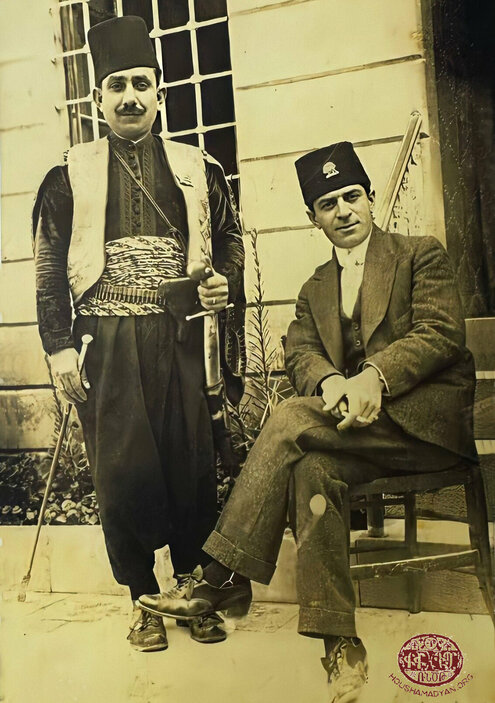

The Khachadourian Family

The Khachadourian family, namely the brothers Haroutyun (Hadji), Khachadour (Djurdji), Krikor, and Nerses (Nerso), were well-known caravaneers and mule keepers. Their business had started with just one mule and had grown into a large “house” (company) that transported people and goods. The business was created by the oldest of the brothers, Haroutyun, who quickly turned one mule into ten. The exceptionally numerous routes served by the Khachadourian Brothers Company covered a large swath of territory. Haroutyun Khachadourian oversaw the Antioch route, Khachadour the Adana-Mersin route, and Krikor and Hagop the Alexandretta route. Nerses Khachadourian’s route depended on the goods he transported and the locations of the clients, who could be as far afield as Aleppo, Alexandria, Svedia (Samandağ), Beirut, and other cities. The brothers also traveled to Gesaria, Sghert, Diyarbakir, and Samsun. Haroutyun Khachadourian was also active in the soap trade. His workers made soap in Antioch, and it was then sold wholesale to the merchants of Ayntab. In 1910-1912, he built a house in the Tepe Pashu neighborhood, described as a “palace.” [42]

Other Merchants and Families Involved in Commerce

In 1909, the Avedis Khanzedian and Partners commercial consortium was created in Ayntab. In 1911, the “Mercantile Printing House” was opened on Soupourdji Boulevard as the local chapter of the company. [43]

Historian and publicist Margos Aghapekian (who had formerly served as an assistant to the governor of Van), served in the 1880s as the Ayntab branch director of the Regie tobacco company. [44]

Senior Priest Karekin Bogharian, before being ordained as a priest, was a merchant. Between 1883 and 1893, he was active in the manisa trade, first as an apprentice, then as a master trader. For two years, he and Garoudj Merdjenian were business partners, but after the expansion of the Merdjenian store, Bogharian was relegated to accounting and office work as a salaried employee. Between 1895 and 1903, he worked as a clerk/accountant in the Leylegian Brothers’ store. [45]

Krikor Leylegian, son of Nerses Leylegian, one of Ayntab’s aghas, was also a renowned merchant. He served as the chairman of several national/community councils and committees. He was one of the founders of the Atenagan Society. [46] Leylegian’s store was located in Millet Khan.

Hagopdjan Yaghoubian was one of the city’s well-known merchants, specializing in the trade of coffee, sugar, and leather. Yaghoubian’s office was located in Millet Khan. [47]

Krikor Kutugian was a native of Talas. He had moved to Ayntab, where he had founded a trading house, [48] with an office in Millet Khan. In 1905-1910, Kutugian was a member of the national political council of Ayntab. He was also an enthusiastic member of the boards of trustees of the Atenagan and Hayganoushian schools. [49]

Armenian caravaneers in Ayntab included the Panosian, Giragosian, and Sanosian families. Some of these families owned 40-50 mules. [50]

Armenag Momdjian was a pistachio farmer. He had purchased a plot of land locally known as Merengish, in the Pash Pounar-Sami area of Ayntab. The property teemed with wild pistachio trees. In 1918, Momdjian produced his first crop of pistachios, and in the following year, 1919, he obtained an exceptional [51] yield from his groves. [52]

Ilias Boshgezenian (Norian) was one of the preeminent merchants of Ayntab before the First World War. After the end of the war, he partnered with the Berghoudian brothers, who were related to him, to create the Norian trading company. The company was very successful in the pistachio trade, which became its primary field of activity. The procurer of the pistachios was Ilias, and the purchaser was the Norian trading house. Later, the company grew to become the large Zenobia trading house. [53]

The hraghats (a device that ground a large amount of grain with the help of fire) [54] was introduced into Ayntab in the 1900s. There were five of them in the city, four of which belonged to Armenians, and one to a Turk. Two of them were owned by Simon and Asdvadzadour aghas, from Arapgir, a third by the Topbashian family from Gurun, and a fourth by the Kurkdjian family. [55]

List of Armenian Traders in Ayntab in 1909 [56]

Below is a list of the commercial centers (khans) in Ayntab, alongside the names of the merchants who conducted business in them, their birthplaces, and the items they sold/traded.

Millet Khan

- Hagopdjan Yaghoubian; Ayntab; coffee and sugar.

- Sahag Bjian; Palu; manisa trade.

- Movses Papazian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Kevork Horomian; Gurun/Gurin; manisa trade.

- Nerses Sulahian and brothers; yarn (thread), leather, etc.

- Madteos Yergaynian and Serop Keshishian; Gesaria/Kayseri; manisa trade.

- Hovhannes Bjian; Palu; manisa trade.

- Basmadjian brothers; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Mgrdich Keshgegian; Arapgir; manisa trade.

- Djebedjian brothers; Ayntab; yarn and leather.

- Moughsi Kevork Leylegian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Pilibbos Aghdjian; Ashodi; manisa and yarn.

- Hadji Movses Leylegian; Ayntab; manisa and yarn.

- Hovhannes Khashkhashian; Gurun/Gurin; retailer.

- Misak Nourhanian; Chenkoush; retailer.

- Garabed Barsoumian; Ayntab; currency exchanger.

- Yeghishe Parseghian; Paghesh (Bitlis); manisa trade.

- Garoudj Merdjanian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Markar Djigerdjian; Arapgir; manisa trade.

- Garabed Kalousdian; Arapgir; manisa trade, etc.

- Armenag Aydjian; Arapgir; manisa and yarn.

- Garabed Arousian; Dikranagerd (Diyarbakir); manisa and yarn.

- Garabed Bazigian; Dikranagerd (Diyarbakir); manisa trade.

Nazar Agha Khan

- Kevork Topbashian; Gurun/Gurin; rug trade.

- Sarkis Sahagian and Hovsep Sahagian; Ayntab; currency exchangers.

- Bedros Ashdjian; Ayntab; currency exchanger and landowner (property owner).

- Sdepan Keshishian; Ashodi; yarn, etc.

- Levon Sahagian; Ayntab; yarn, etc.

- Hovhannes Piranian; Gurun/Gurin; manisa trade.

- Garabed Chakudjian; Gesaria; yarn, etc.

- Krikor Yesayan and Puzant Soukiasian; Ayntab; calico and yarn.

- Hagop Arslanian and sons; Tokat; copper.

- Krikor Kabakdjian and son; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Roupen (saatdju); Ayntab; watch maker.

Hadji Eomer Khan

- Manouel Topbashian; Gurun/Gurin; soap.

- Garabed Babigian; Ashodi; manisa trade.

- Toros Sahagian; Ashodi; currency exchanger.

- Melkon Kabakian and brothers; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Haroutyun Levonian and brothers; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Dzeroun Dzernigian; Malatia; hokka malu (ink seller).

- Hovhannes Saatdjian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Hovhannes Levonian; Ayntab; currency exchanger and pistachio trade.

Sahagian-Ghazarian Khan

- Kalousd Ghazarian and his sons Toros, Garabed, Hagop, and Nazar; Ashodi; manisa trade, etc.

- Nazaret Manoushagian; Ayntab; imported items.

- Kevork Tatarian; Gesaria (Kayseri); manisa trade.

- Sarkis B. Nazarian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

Iki Kapulu Khan

- Dikran Roupen Yegavian; Arapgir; manisa trade, etc.

- Sarkis G. Nazarian; Ayntab; manisa trade, etc.

- Garabed Nazarian; Ayntab; manisa trade, etc.

- Kevork Demirdjian; Ayntab; iron.

- Movses Ammiyan; Ayntab; cotton.

- Garabed Hindoyan; Ayntab; oil, etc.

Yuksukdju Khan

- Movses Arslanian; Ayntab; copper.

Emir Ali Khan

- Y. Karamanougian and brothers; Ayntab; manisa trade.

Basmadjian Khan

- Hadji Haroutyun Basmadjian; Ayntab; trader.

Merchants Conducting Business Outside of Khans

- Hanne Effendi Kurkdjian; Ayntab; soap.

- Garabed Bey Nazaretian; Ayntab; soap and produce.

- Ardashes Adanalian; Sepasdia (Sivas); soap.

- Sarkis Kradjian; Ayntab; embroidery.

- Hovsep Arakelian; Ayntab; manufacturing and the trade of sheep.

- Garoudj Karamanougian; Ayntab; manufacturing and embroidery.

- Garabed Yaghsuzian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Haroutyun Ammiyan; Ayntba; manisa trade.

- Melkon Karamanougian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Hagop Bogharian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Kevork Djebedjian; Ayntab; manisa trade.

- Ohan Kupelian; Ayntab; tailor.

- Nazar Beredjiglian; Ayntab; currency exchanger.

- Haroutyun Beredjiglian; Ayntab; currency exchanger.

- Misak Mateosian; Ayntab; Singer sewing machines and textile.

- Hrand Sulahian; Ayntab; rugs.

- Hagop Bezdjiyan; Ayntab; pharmaceuticals.

- Haroutyun Kurkdjian; Ayntab; manufacturing.

- Hovsep Kendirdjian; Ayntab; manufacturing and landowner.

- Minas Kendirdjian; Ayntab; manufacturing.

- Movses Topdjian; Ayntab; manufacturing.

- Kevork Loshkhadjian; Ayntab; manufacturing.

- Hovhannes Beredjiglian; Ayntab; currency exchanger.

- Apraham Babigian; Ayntab; currency exchanger.

- Toros Kradjian; Ayntab; merchant.

- Kevork Kradjian; Ayntab; merchant.

- Hovhannes Djebedjian; Ayntab; landowner.

- Yeghia Kharadjian; Ayntab; merchant.

- Krikor Djebedjian; Ayntab; merchant.

- [1] Pyuragn Weekly Periodical, Constantinople, 24 February 1907, n. 17-18, p. 101.

- [2] The word “khan” translates into “home.” This was the name given to large commercial centers that included offices, stores, and other commercial premises.

- [3] Levon Chormisian, Hamabadger Arevmdahayots Meg Tarou Badmoutyan [Overview of One Century of Western Armenian History], volume 1 (1850-1878), Beirut, Sevan Publishing House, 1972, pp. 170-171.

- [4] Naoum Dasho, “Architectural Innovations in Ayntab,” Pyuragn Weekly, 28 July 1908, n. 27, pp. 859-861.

- [5] Vart, “The City of Ayntab,” Araks, Saint Petersburg, Book 2, May 1888, p. 58.

- [6] Pyuragn Weekly, 22 July 1906, n. 26, p. 622.

- [7] N. Baghdoyan, Ayntabi Lernakavari Masin [On the Mountainous District of Ayntab], Aleppo, 18 June [19]19, handwritten, pp. 8-9 (see Noubarian Library, Paris, Andonian Collection, File n. 4, Ayntab, 0023-0024).

- [8] Father Soukias Eprigian, Badgerazart Pnashkharhig Pararan [Illustrated Dictionary of the Natural World], volume 1, St. Lazarus/Venice, 1903, p. 145; Cilicia: Ports Ashkharhakroutyan Arti Giligyo [Attempt at the Geography of Modern Cilicia], Saint Petersburg, I. Liberman Printing House, 1894, p. 356.

- [9] Naoum Dasho, “Architectural Innovations in Ayntab,” p. 860.

- [10] Pyuragn Weekly, 8 December 1907, n. 50.

- [11] Krikor Bogharian, “Nigoghos Agha Nazaretian (1843-1899),” Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots [History of the Armenians of Ayntab], volume 2, edited and compiled by A. Sarafian, Los Angeles, 1953, hereby BAH 2, p. 751.

- [12] Krikor Bogharian, “Nigoghos Agha Nazaretian (1843-1899),” Hay Ayntab [Armenian Ayntab], Beirut, 1964, n. 4 (16), pp. 9-10.

- [13] Ibid., p. 10.

- [14] Popokhial Dramatrouyunk Azkayin Sahmanatroutyan yev Deghegakir Veraknnitch Hantsnajoghovo ar Azkayin Unth. Joghovn [Changing Attitudes towards the National Constitution and Report to the Supervisory Committee of the National Council], Constantinople, H. Kavafian and H. Baronian Printing House, 1874, pp. 37-38.

- [15] Azkayin Sahmanatroutyun Hayots [National Constitution of Armenians], 1860, Constantinople, p. 9 and 21.

- [16] K.B. [Krikor Bogharian], “Nigoghos Agha Nazaretian (1843-1899),” BAH 2, p. 753.

- [17] Ibid., pp. 752-753; K. Bogharian, “Nigoghos Agha Nazaretian (1843-1899),” Hay Ayntab, Beirut, 1964, n. 4 (16), p. 10.

- [18] Krikor Bogharian, “Nigoghos Agha Nazaretian (1843-1899),” Hay Ayntab, Beirut, 1964, n. 4 (16), p. 11.

- [19] Bishop Papken Guleserian, “The Holy Mother-of-God Church of Ayntab,” Badmoutyun Ayntabi Hayots, volume 1, edited and compiled by Kevork A, Sarafian, Los Angeles, 1953, hereby BAH 1, pp. 421-425.

- [20] Ibid., pp. 653-654.

- [21] Senior Priest Mesrob Keoshgerian, “Bedros Agha Ashdjian,” BAH 2, p. 755.

- [22] K. Bogharian, “Nighoghos Agha Nazaretian (1843-1899),” Hay Ayntab [Armenian Ayntab], 1964, n. 4 (16), pp. 9-11.

- [23] K. Bogharian, “The Boarding School of Cilicia, Ayntab (1873-1877),” Nor Ayntab, Beirut, 1973, n. 3 (55), p. 18.

- [24] K. Bogharian, “Nighoghos Agha Nazaretian (1843-1899),” Hay Ayntab [Armenian Ayntab], 1964, n. 4 (16), p. 11.

- [25] Nazar Agha Nazaretian’s other son, Artin Nazaretian, settled in Aleppo after the massacres of 1895, then moved to Cyprus, and finally, to Alexandria. He was engaged in the trade of dried fruits, and founded the Hassan Kef tobacco factory, to which his sons, Nazar and Nshan, also contributed greatly. Artin Nazaretian was a member of the national political council. See “Garabed Bey Garabedian,” BAH 2, p. 756.

- [26] Ibid.

- [27] K. Bogharian, “Nazaret Manoushagian (1874-1933),” Ayntabagank, volume 2, Mahartsan, Atlas Printing House, Beirut, 1974, pp. 537-539; K. B. [Krikor Bogharian], “Nazaret Manoushagian (1874-1933),” BAH 2, pp. 767-768.

- [28] K. Bogharian, “Kalousd Agha Ghazarian (1845-1923),” Ayntabagank, volume 2, p. 167.

- [29] Ibid., p. 170.

- [30] Ibid., pp. 167-170.

- [31] Araks, Saint Petersburg, 1887, book 1, November, p. 21.

- [32] “Kalousd Agha Ghzarian,” BAH 2, p. 757.

- [33] Senior Priest Mesrob Keoshgerian, “Bedros Agha Ashdjian,” BAH 2, pp. 755-756.

- [34] Hagop Kabbendjian, “Garoudj Karamanougian (1846-1916), BAH 2, pp. 769-770.

- [35] R.[obert] Djebedjian, Autobiography, Memoirs, and Works, Aleppo, 1999, p. 19.

- [36] “Giligetsi” (Vahan Movses Kurkdjian), “Hrand K. Sulahian,” BAH 2, pp. 758-759.

- [37] Y. B. [Yervant Babayan], “Hrand K. Sulahian,” Nor Ayntab, 1972, n. 2-3 (50-51), pp. 10-11.

- [38] K. Bogharian, “Adour Agha Niziblian (1826-1893),” Hay Ayntab, 1967, n. 2 (26), p. 18.

- [39] M. G. [Manase Garabed] Papazian, “Adour Niziblian and the Niziblian Museum,” Hayasdani Gochnag [Clarion of Armenia], New York, 21 November 1931, n. 47, p. 1486.

- [40] Loutfi Haleblian, “Autiobiography of Adour Agha Niziblian,” Hay Ayntab, 1967, n. 3 (27), pp. 28-29.

- [41] Dr. Maurice Kachian, “Nerses Baronian,” BAH 2, p. 771.

- [42] K. Bogharian, Ayntabagank, volume 2, pp. 436 and 480-482.

- [43] K. Bogharian, “Notes on the History of Publishing and Journalism in Ayntab: Father Karekin Bogharian’s Letter,” Hay Ayntab, 1966, n. 3 (23), pp. 42-43.

- [44] V. M. [Vahan Movses] Kurkdjian, “Outside and Around the Vartanian School,” Hayasdani Gochnag, New York, 17 November 1928, n. 46, p. 1456.

- [45] K. Bogharian, “Autobiography,” Ayntabagank, volume 2, p. 11.

- [46] K. Bogharian, “The Boarding School of Cilicia, Ayntab (1873-1973),” Nor Ayntab, 1973, n. 4 (56), p. 33.

- [47] K. Bogharian, “Dikran Yakoubian (1891-1969),” Ayntabagank, volume 2, p. 698.

- [48] Nor Ayntab, 1973, n. 1-2 (53-54), p. 114.

- [49] K. Bogharian, “Hrand K. Armen (Hrand Kutugian) (1895-1973),” Ayntabagank, volume 2, p. 347.

- [50] Kevork H. Barsoumian, “The Crafts of Ayntab,” BAH 2, p. 290.

- [51] In the first two months of the battles for the self-defense of Ayntab in 1920, stored, purchased, and requisitioned pistachios were the primary source of nutrition for the city’s encircled Armenians. Pistachios were ground into flour and baked into bread. They were even pressed to obtain oil. The dried outer husks were smoked as a replacement for tobacco (source: K. Bogharian, “Armenag Momdjian (1878-1955),” Ayntabagank, volume 2, p. 78).

- [52] K. Bogharian, “Armenag Momdjian (1878-1955),” Hay Ayntab, 1965, n. 2 (18), p. 47.

- [53] K. Bogharian, “Ilias Boshgezenian (Norian) (1880-1942),” Ayntabagank, volume 2, p. 268.

- [54] Mshag, Tbilisi, 24 February (8 March) 1882, n. 31, p. 1.

- [55] Kevork H. Barsoumian, “The Crafts of Ayntab,” BAH 2, p. 290.

- [56] This list prepared by Levon Garbis Nazarian (Beirut); see BAH 2, pp. 311-312.