Yagjian/Yaghdjian Collection – Austin, Texas

Author: Marc Yagjian, 03/10/2023 (Last modified: 03/10/2023).

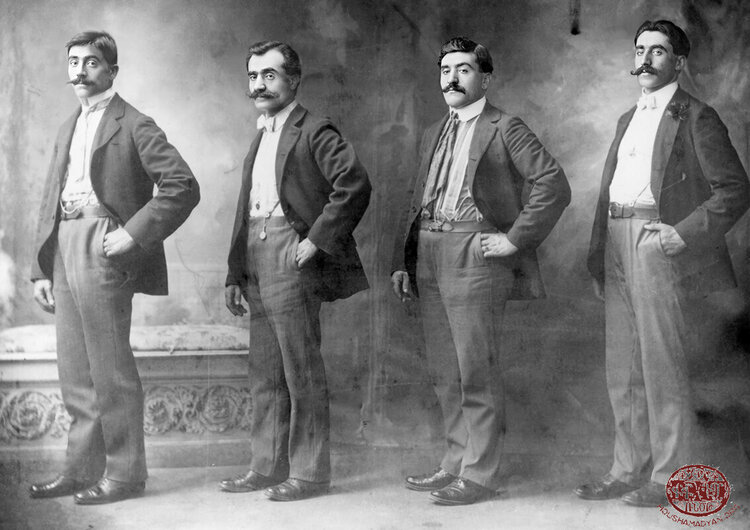

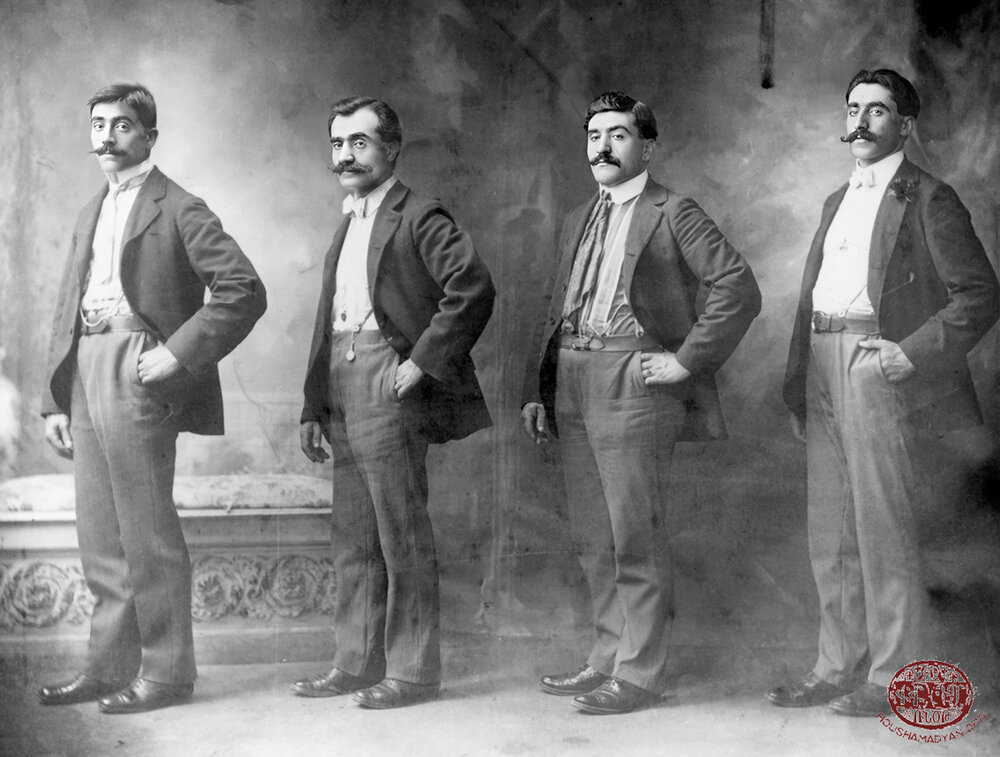

The Yagjian Brothers of Worcester

In 1881, Hovanes “John” Yagjian (Yaghdjian) arrived in Worcester, Massachusetts. He had travelled from his home in Keserig (present-day Kızılay), located in the Kharpert/Harput valley, in the Ottoman Empire. He reached Ellis Island alongside other Armenian immigrants, including Minas Aroian and George Juskalian. These youths were 16- to 19 years old when they arrived, perhaps even younger. They were sent to America by their families to explore new opportunities. The three young men soon found an inexpensive room to share in a boarding house on Fountain Street. They found low-skilled jobs at the Washburn & Moen wire factory. They took turns working shifts in the factory and staying home to cook and perform household chores. [1]

These young men were among the earliest Armenians to immigrate to Worcester. In the early 1880s, it is estimated that only about 10 to 15 Armenians lived in the city [2]. Why did these Armenian boys choose Worcester? How did they know of it?

In the early 19th century, America and Worcester were unknown to Armenians living in their native lands. Beginning in the 1830s, across the world and in New England, Protestant churches began organizing missions with the aim of conducting charitable activities worldwide. Armenians in the Ottoman Empire soon became a favorite target of these missionaries, as they were receptive Christians with a literate, developed culture.

As early as 1856, a Protestant Evangelical church was opened in Kharpert, followed in 1859 by a seminary to train native-born Armenian pastors. In 1878, missionaries founded the Armenian College of Kharpert, which was quickly renamed as the Euphrates College after objections from the Ottoman authorities. This college was to have an enormous influence on the region and spurred a wave of emigration of Armenians to America, and to Worcester in particular. While attending the college, Armenian students learned of a wire factory in Worcester, Massachusetts, which employed foreigners. John Yagjian and his friends were among the earliest to pursue the siren song of Worcester.

During the 1880s, John lived on Arch Street, at the heart of Worcester’s Armenian community. In his home, he hosted meetings that shaped the community’s future and kept the Armenian spirit alive. In 1888, a group of Worcester Armenians, including John, formed the “Armenian Club.” Thanks to the growing number of Armenians arriving in Worcester, primarily from Kharpert, the club soon had more than 300 members. In 1889, John and his fellow community leaders established the first Armenian Apostolic Church parish in the United States – the Armenian Church of Our Saviour. Services were held in rented spaces while they reached out across the diaspora to raise the funds necessary to build a church.

During this time and well into the 1890s, the Armenian community of Worcester consisted almost exclusively of men. Contemporary estimates indicate that of the 300 Armenian immigrants in Worcester, only five were women. Many of the immigrant men expected to return to their families after earning some money. However, the Ottoman government soon restricted the movement of Armenian women out of the country, and the gender imbalance in the community became even more exacerbated.

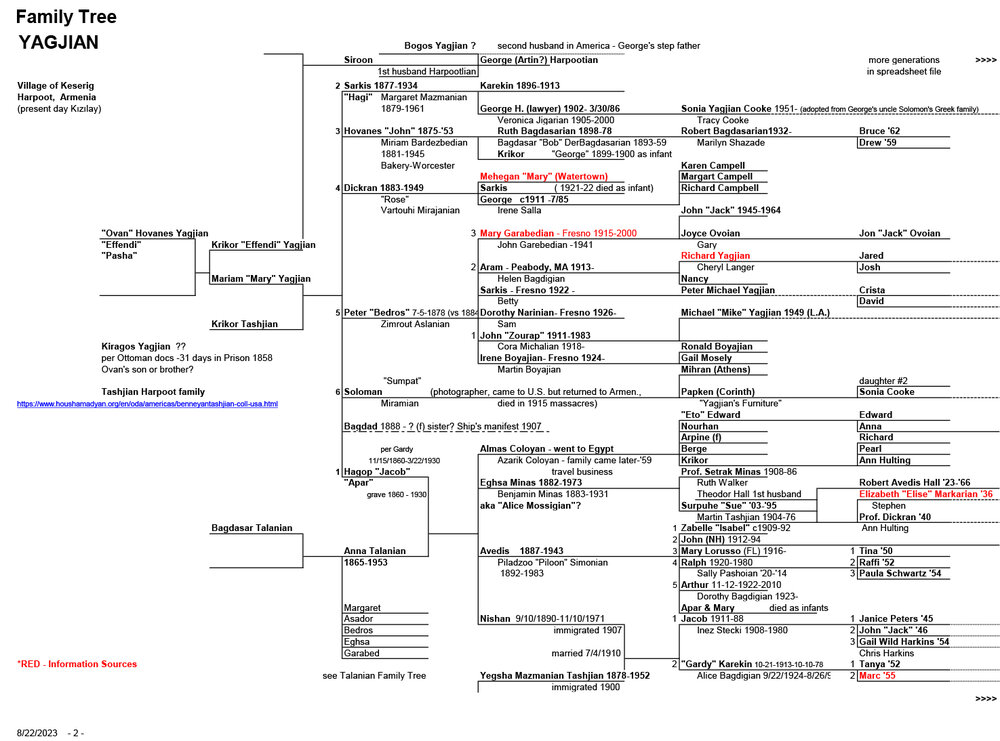

John Yagjian was the third of six Yagjian brothers (Hagop, Sarkis, John, Dickran, Peter, and Soghomon). The oldest of the brothers, Hagop, appears to have followed John to Worcester in 1882, and to have returned to Keserig a few years later. In 1890, Hagop Yagjian (30 years old), Dickran (24 years old), Peter (21 years old) and Soghomon (18 years old) left Keserig together to join John in Worcester. Hagop left behind his wife Anna, daughters Almas and Egsha, and sons Avedis and Nishan. Nishan was born in that same year, possibly after Hagop’s departure. Dickran, Peter, and Soghomon were all unmarried.

In those early days in Worcester, John and his four newly arrived brothers opened a bakery on Southbridge Street. They delivered bread by horse and buggy throughout Worcester County and the Boston area. They saved what money they earned and were staunch supporters of the Worcester Armenian community.

In their hearts, John and his brothers were always sons of their agricultural hometown of Keserig. There, the Yagjians were a prominent merchant family that owned a sizable estate, fields and orchards, horses, livestock, and gardens. The extended family, consisting of perhaps 35 to 50 individuals, lived on the family estate, described as “a walled palace, bedecked with trees and gardens.” [3]

The Yagjian brothers felt deeply proud of their grandfather, Hovaness “Ovan” Yagjian, whom they revered. He had elevated the family to prominence in Kharpert. Ovan’s story has been the enduring core of the Yagjian family’s oral history – the one shared thread across the disparate family branches.

Hovaness “Ovan” Yagjian/Yaghdjian

As noted in Kharpert and Its Golden Valley [Kharpert yev Anor Vosgeghen Tashdu], Hadji Ovan/Ohan Yagjian was born in Kesirig to a humble family, probably in 1795. Thanks to his talents and tenacity, he earned prominence and respect not only across the province of Kharpert, but also within the official circles of the Ottoman Empire. Over the years, his story became legendary, transforming him into a remarkable and fascinating hero. [4]

During the Russo-Turkish war (most likely the Crimean War of 1853-1856), Ovan became a supplier of food to the Ottoman army. He used a caravan of mules to conduct business. At one point during that war, Ottoman forces were encircled by Russian troops, and were threatened with annihilation. Under these circumstances, transporting food to the encircled army was a highly risky proposition. The Turkish command was convinced that it was an impossible task, but Ohan Yagjian found the solution. He tied felt around the mules’ hooves, and with the whole caravan loaded with food, succeeded during the night in breaking the blockade and supplying food to the desperate and hungry soldiers. For this and many other services rendered to the Ottoman state, Ohan Effendi Yagjian was invited by the Sultan to Istanbul to be honored. He received an honorary medal, a sword, and a uniform. During his stay in Istanbul and upon his request, he obtained imperial authorization for the construction of an Armenian church and monastery in Keserig, as well as the renovation of many other churches and the construction of new steeples. Yagjian gained a great deal of esteem, particularly in the Kharpert region. In addition to churches, he also played a major role in the construction of Armenian schools. Many government judges and Ottoman officials were cowed by him. He died before the Hamidian massacres of 1895, although some sources indicate that he died as early as 1885. He was buried with great pomp in the monastery of Saint Mamas. It is said that while leading renovation work at Saint Mamas, he had instructed the workers to prepare his own future grave. [5]

Ovan Yagjian had two children, Krikor Effendi and Mariam, both likely born in the 1830-1840s. Mariam married Krikor Tashjian, and together they had six sons, the six Yagjian brothers, born between 1860 and 1872. Mariam’s brother, Krikor Effendi Yagjian, had no sons, but at least one daughter named Siroon. To preserve the Yagjian name and to honor Ovan, Krikor Tashjian and Mariam Tashjian’s (nee Yagjian) sons, Hagop, Sarkis, John, Dickran, Peter, and Soghomon, all adopted their mother’s maiden surname of Yagjian.

Ovan Yagjian passed away sometime before 1894. Ovan’s son, Krikor Effendi, became the head of the family. In the same year, after spending a few years with his four brothers working in their Worcester bakery, Soghomon returned to the family’s estate in Keserig. Soon thereafter, in 1895, the people of Keserig faced the Hamidian massacres.

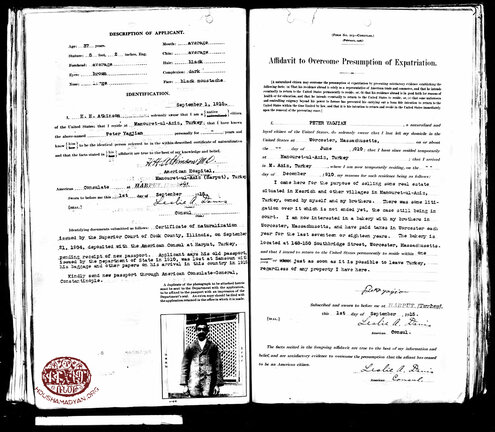

Peter Yagjian’s replacement U.S. passport application, September 1, 1915, U.S Consulate, Kharpert. With Affidavit to Overcome Presumption of Expiration.

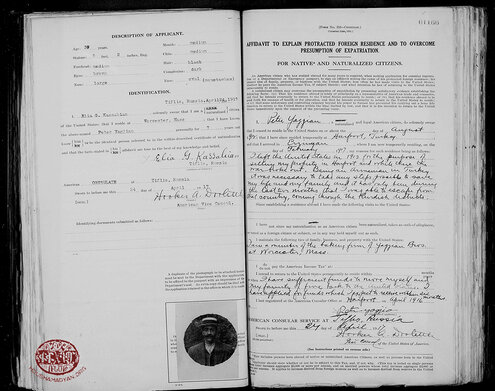

Peter Yagjian’s Affidavit to Explain Protracted Foreign Residence to Overcome Presumption of Expatriation .Tiflis - April 27, 1917.

The Yagjian Family, Keserig, and the Hamidian Massacres

During the 1895 Hamidian massacres, as noted in Vahé Haig’s work on Kharpert, more than 120 Armenians were killed in Keserig. It was during these events that Keserig Armenians organized their self-defense. Hadji Effendi (Krikor) Yagjian, though still employed by the state, played a major role in this effort. By the end of September 1895, the massacres and plunder had reached nearby villages. The Turkish beys of Keserig invited an Armenian delegation to Hamdi Bey’s konak (mansion). The delegation consisted of two priests and more than 20 Armenian youths. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the prevailing situation and how violence could be avoided in Keserig. Krikor Effendi suspected that the invitation was a trap, but eventually decided to attend with a group of other Armenians. Some of the men entered the konak with him, while others were stationed outside as lookouts. The first suggestion that Krikor Effendi made during the meeting was for the local authorities to distribute 50 rifles to Armenians, with which they would be able to defend themselves. The Turks initially agreed, but then, on the next day, they announced that there was no need for rifles, as army troops were very close to the village and would intervene if necessary. [6]

Turkish soldiers, dressed in local garb and pretending to be Kurds, were already killing and robbing Armenians in distant villages. One day in late September, Turks began shooting at Armenian homes in Keserig. The Yagjian, Der-Hovannessian, and Terzian homes were struck by bullets. Turkish troops then began converging on Krikor Yagjian’s house, but Krikor Effendi, with a group of armed youths, fought back and repelled the attack. The exchange of fire lasted some four hours. But afterwards, the Turkish soldiers returned, this time in uniform. The whole village was encircled, and the troops began arresting Armenians. The first person to be arrested was Krikor Effendi Yagjian, who was forced to hand himself in alongside 24 of his friends. The violence and plunder in Keserig lasted three days. [7]

A month later, with Keserig still in ruins, a new wave of arrests began. Among the detainees were Mendzig Agha Yagjian, Soghomon Yagjian, Hadji Sarkis Yagjian, and others not related to the family. The arrested Armenians were initially held in Mezire prison. Four months later, they were exiled to Sivas, where they were put on trial. The men were accused of being revolutionaries and were sentenced to death. After the verdict, Krikor Effendi Yagjian sent a telegram to the Ottoman Grand Vizier (Prime Minister), a friend of his father’s. The Grand Vizier intervened in favor of the prisoners, and they were soon released. On December 29, 1897, the freed men victoriously returned to Keserig. [8]

The family history does not document how news of these incidents and massacres was received by the Yagjian brothers in Worcester. However, it is well-documented that the Hamidian massacres and Armenian revolutionary politics caused a great deal of grief, despair, stress, and turmoil in Armenian community in Worcester. Armenian immigrants were now much more anxious to bring their families to the United States and establish permanent roots in the country. In 1897, the U.S. government obtained the consent of the Ottoman Sultan to allow the wives and families of Armenian citizens living in the United States to join them.

For the Yagjians, life continued in America in the early 1900s.

In 1902, Hagop’s oldest son, Avedis (aged 15), who had not seen his father since the age of three, joined him and his three uncles in Worcester. Hagop’s wife, Anna; daughter Egsha; granddaughter Surpuhe; and son Nishan, remained in Keserig until immigrating to Worcester in 1906/1907. They traveled overland to Samson where they boarded a ship. Immigration screening in Europe, likely Marseille, separated 16-year-old Nishan from his mother and sister. Nishan’s solo journey to Worcester took him more than a year traveling from Marseille to America. He spent much of that year in Liverpool as a taylor’s apprentice earning his final passage to America. It was whispered, but not openly discussed, that when Nishan arrived in America he was declared to have trachoma and denied entry. Nishan then somehow jumped ship in Providence harbor, arranging for a small boat to take him ashore at night.

Sarkis Yagjian finally arrived in Worcester in 1909. His wife, Margaret, and sons, Karekin (aged 15) and George (aged eight), joined him in Worcester in 1911.

John continued to be a leader in the Worcester Armenian community and the parish of the Armenian Church of Our Saviour. He also continued to run the family’s bakery on Southbridge Street. He married Miriam Bardezbedian, and had a daughter, Ruth.

In 1911, Dickran Yagjian, now in his 40s, married Rose Mirajanian in Worcester. They had two sons and a daughter. One of their sons died in infancy.

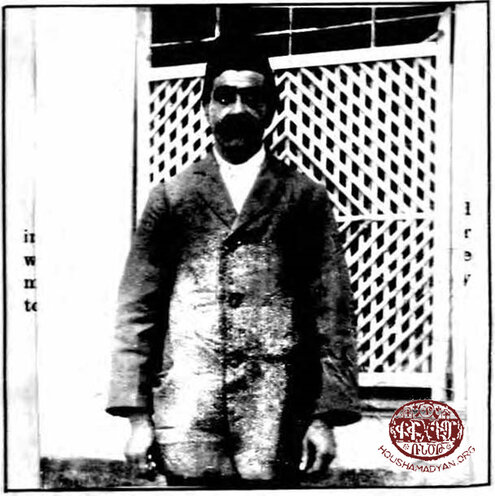

Peter Yagjian became a U.S. Citizen in 1904. He then returned to Keserig in 1910, where he married and had three children between 1911 and 1915.

The Yagjian’s Southbridge Street bakery was the foundation of the family’s economic foothold in America. The brothers and their growing families owed much to this bakery. As the family further expanded in the early 1900s, particularly with the birth of the next generation of sons, many members of the family created separate households and new small businesses.

By the eve of the genocide in 1915, the four oldest Yagjian brothers and their families were well-established in Worcester. The two youngest among them, Peter and Soghomon, returned to Keserig and lived in the family’s estate, along with their uncle, Krikor Effendi; their parents, Mariam and Krikor Tashjian; and an unknown number of other Yagjians. When the Armenian Genocide began and the massacres reached Keserig in May 1915, both brothers’ families were displaced. Each family had its own story of survival.

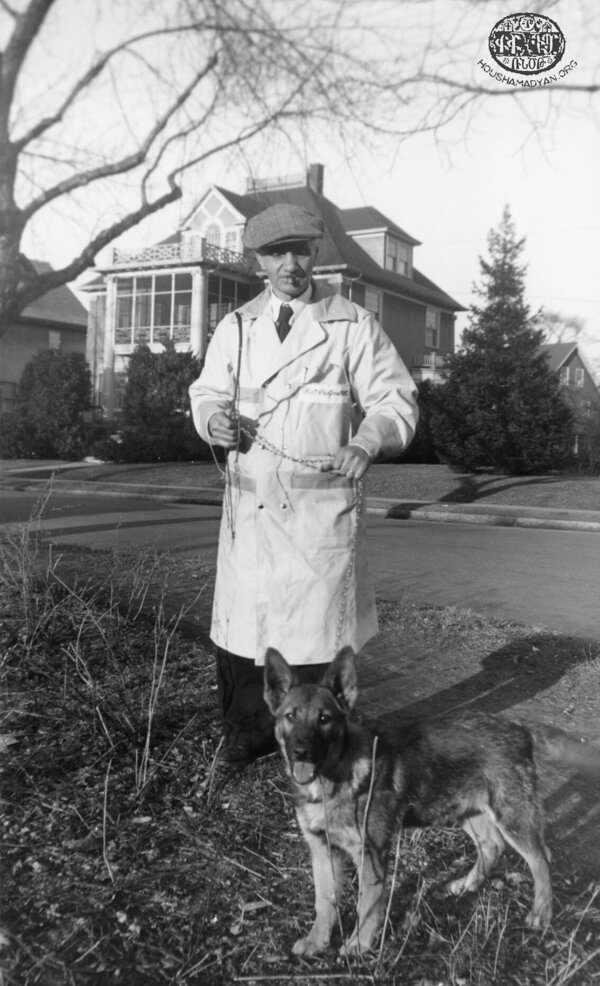

Peter’s Story

Peter had returned from Worcester to Keserig around 1910. There, he married Zimroot Arslanian. The couple had three children: Zohrab (“John;” born in 1911), Aram (born 1913), and Mary (born in 1915). When the genocide began, Peter and his family fled home and attempted to escape. As Peter was a U.S. citizen, he had a valuable advantage – the potential for assistance from America, in addition to the Turks’ unwillingness to harm U.S. citizens. On September 1, 1915, several months after the start of the Kharpert massacres and deportations, Peter filed a U.S. passport application through the U.S. Consulate in Kharpert, Turkey.

Peter’s passport application stated that his old passport “was lost in Samsun with my baggage and other papers upon my arrival in the country in 1910.” Peter elaborated: “I came here to sell some real estate situated in Keserig and other villages in Mamuret-ul-Aziz, Turkey, owned by myself and my brothers. There was some litigation over it which has not ended yet, the case still being in court. I now run a bakery with my brothers in Worcester, Massachusetts, and have paid taxes in Worcester for seventeen or eighteen years. The bakery is located at 148-150 Southbridge Street, Worcester, Massachusetts…. I intend to return to the U.S. permanently as a resident within one year, or as soon as it is possible to leave Turkey, regardless of any property I have here.”

From this point on, Peter worked tirelessly to flee to America with his family. It was a challenging and dangerous situation. Peter used his U.S. citizenship and his profession as a baker to his advantage. He somehow positioned himself as a bread supplier for the Ottoman army. He kept moving eastward with his family, away from the conflict zone. When challenged on his Armenian identity, he would brandish his U.S. Consulate papers and convince officials that he played a critical role in supplying the Ottoman army with food. In addition to his family, Peter saved several Armenian boys and others by employing them in his bakeries.

On April 27, 1917, Peter made it to the U.S. Consulate in Tbilisi, Georgia. He had last registered with the American Consular Office in Kharpert in April 1916. On a new “Affidavit to Explain Protracted Foreign Residence and to Overcome Presumption of Expiration,” he stated that since February 1917, he had been temporarily residing in Erzindjan/Erzincan. He provided the following explanation: “I left the United States in 1912 for the purpose of selling my property in Kharpert. While I was still there, the war broke out. Being an Armenian in Turkey, it was necessary to take any steps possible to save my life and my family. It has only been during the last two months that I was able to escape that country, traveling across the Kurdish districts. (…) I am one of the owners of a bakery firm, Yagjian, Bros., in Worcester, Mass. (…) I have sufficient funds to move myself and my family of five back to the United States. I have applied for funds which I expect to receive within six months.”

Eventually, over 14 months later, in 1918, Peter and his family found their way to Archangel, Russia, then on to the United States. The manifesto of the ship “City of Cairo,” dated September 15, 1918, lists Peter Yagjian, his wife, and their three children as second-class (not steerage) passengers, traveling from Archangel, Russia, to Montreal. They planned to join John Yagjian at 146-148 Southbridge Street, Worcester.

In America, Peter had three more children: Sarkis, Irene, and Dorothy. At some point, Peter moved his family to Cambridge and opened a bakery there. His sons Sarkis, Aram, and John all helped in the bakery. However, Peter’s eyesight began failing, and he was cared for by his wife until his death before the outbreak of the Second World War. The family’s bakery also closed around this time.

Soghomon’s Story

Before 1915, Soghomon Yagjian had married Yeghisapet Kalunian, a native of the city of Kharpert. Soghomon and Yeghisapet had four children: Siranoush (born circa 1905), Mihran, Papken, and Zabel (born circa 1913). Presumably, the family lived in the Yagjian family home in Keserig.

The remarkable story of Soghomon’s family was published by Houshamadyan in October 2022. It was titled Yaghdjian/Yiagjian Collection – Athens.

Soghomon did not survive the genocide. However, Yeghisapet and their four children did. After several years of exile and hardship, Yeghisapet and three of her children settled in Corinth, Greece. Her oldest daughter, Siranoush, remained in the Keserig area until her death. Until the recent publication of the Yaghdjian/Yiagjian Collection – Athens article on Houshamadyan, the American Yagjians had no knowledge of what had happened to the family’s estate in Keserig. The Corinth Yagjians now tell us that it was the Yagjian home in Keserig that housed the local American Near East Relief (NER) orphanage, which sheltered 100 to 200 orphans until 1922, when the Turkish government forced NER to close its orphanages across Turkey.

As for Krikor Effendi Yagjian, when the Armenian Genocide began in 1915, the Turks spared his life due to the prominence of the family, most likely after receiving substantial bribes. Krikor Effendi; his wife; his daughter, Siroon; and the latter’s young son, George, were exiled to a location in Turkey or Russia instead of being killed with other Armenians. Siroon’s husband was among the victims of the Genocide. Krikor Effendi never came to America. He likely perished during the many conflicts across the region. The fate of Mariam and Krikor Tashjian, the parents of the six Yagjian brothers, is still unknown.

Krikor’s daughter, Siroon, and her only child, George, eventually made it to America, after having survived genocide, exile, and the ensuing years. Siroon was a first cousin of the six Yagjian brothers of Worcester, and they worked tirelessly for several years to bring her and George to America, despite considerable legal and immigration-related challenges. Siroon and George finally arrived in America in 1923, where Siroon married a second time, to a man named "Yagjian" from Rhode Island. He was thought to have been a business partner and cousin of the family. This may have been a marriage arranged prior to her arrival, to ensure that she had permission to immigrate to the country. The couple settled in Rhode Island. “Siroon Yaghjian,” nee Harpootlian, is listed in official documents as having died in Boston, at the age of 80, in 1967.

Siroon’s niece, Mary Garabedian, remembered “Auntie” Siroon as: “A wonderful, humble person. She had married in the old country at a very young age to a man named Harpootlian, a prominent businessman. We assume he was killed by the Turks. (…) The children were told she was a ‘princess’ in the old country. It was said that ‘she didn't even know how to comb her own hair,’ since servants had always done it for her.”

During the 1890s and 1900s, while the Yagjian brothers and their families were immigrating to Worcester, another branch of direct descendants of Ovan and Krikor Yagjian immigrated to the Providence, Rhode Island area. Although the members of this branch of the family have drifted apart and lost all knowledge of or connection with their Worcester cousins, they’ve retained the oral history of Ovan Yagjian. Between 1897 and 1927, U.S. immigration records attest to the arrival at least 48 Yagjians in America, most originating from Keserig or Kharpert, and most likely related to the Keserig Yagjian clan.

After permanently settling down in America with their families, the Yagjian brothers of Worcester spend the 1920s building a solid financial foundation for their future. The five brothers and their families grew and assimilated into broader New England and American society. Many of their children, grandchildren, and descendants pursued higher education and accomplished much in commerce, academia, and the professions. Today, the Yagjian family is largely dispersed and assimilated, though many of them continue to embrace their Armenian identity with pride.

- [1] John H. Aroian,Mountains Stand Firm, GreenHill Publishing, NY, 1977.

- [2] Dr. Hagop Martin Deranian, Worcester is America, Bennate Publising, 1998, p. 19

- [3] Vahé Haig, Kharpert yev Anor Vosgeghen Tashdu [Kharpert and Its Golden Valley], New York, 1959, p. 885.

- [4] Ibid.

- [5] Ibid., pp. 885-886.

- [6] Ibid., p. 883.

- [7] Ibid.

- [8] Ibid; Houshamadyan - Kazanjian collection - Los Angeles - Description of the Massacres of Armenians in 1895 in the Kharpert Area – Witness Testimony.