Kazandjian-Topdjian Collection - Aleppo

Author: Maroush Yeramian, 26/08/21 (Last modified 26/08/21) - Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

On both sides, the great-grandfathers, both paternal and maternal, were Armenians, who lived in Aleppo long before the massacres and the resettlement of migrants to Aleppo.

It is said that the history of Armenians in Aleppo dates to the era of Tigran the Great. Others note the tenth century. The mother church of Aleppo, the St. Karasoun Manoug (Holy Forty-Martyrs) Church, has a much older, subterranean church that is only opened on special occasions and must be accessed from a very narrow opening, that dates to the sixth century A.D. and is evidence of the early existence of Armenians in Aleppo.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Armenians of Aleppo began to undergo Arabization. All the ceremonies of the church were in Arabic. The Armenians had completely forgotten the Armenian language, and even their names and family names were Arabic: The names of the relatives were also in Arabic: Zekiyeh, Medjideh, Ekmekdji (or Ekmekdjian/Hatsakordzian), Deokmedji, Adjami, Nahhas, (Kazandjian), Kayyali, etc. The names used to denote relatives were also Arabic: khalo, martkhalo, khaleh, ammeh (for the Armenian keri (mother’s brother), kergin (wife of the latter), morakouyr (mother’s sister), horakouyr (father’s sister).

The arrival of Armenian migrants to Aleppo during and after the 1915 Genocide seemed to have shaken the conscience and national feelings of the local Armenians. Not only did they rush to help the migrants, but they also begin to convert to the mother tongue. Names changed, but last names remained the same, since Syrian law strictly prohibits changing names, especially family names.

My paternal grandfather, Haroutiun Kazandjian, traveled with his family to Dikranagerd/Diyarbekir in the early 1800s to reach Iskenderun/Alexandretta (a seaside town in what was then Syria, then Turkey), where he waited to board a ship sailing to America and the “Promised Land”.

"But how did they get a visa?" I ask.

“In those days, of course, there were no visas. You boarded the ship, reached New York, the gateway to the promised land, and after registering your name there, you went wherever you wanted. God's country is infinite ...”

They reached Aleppo and decided to rest. A few days later, Grandpa Haroutiun tells his wife:

- It is a peaceful, safe city. The people are kind and open-hearted. Shall we stay?

The woman says nothing. So, they stayed in Aleppo. They worked, and with the sweat of their brow they made a living and more.

My maternal grandfather, Philip Topdjian, was an Ottoman army gendarme in Aleppo. He married three women in succession. He died before the third passed away.

"That disgusting priest cursed me," said the third woman, "I was not destined to die."

The priest might have committed a robbery and gendarme Philip chased him. The priest enters the cemetery, followed by gendarme Philip, and there his foot hits a tombstone. Philp falls to the ground ... He doesn’t get up. Judging by the stories passed down, gangrene sets in, and he dies suffering.

Philip has six sons and two daughters from his three wives. One of the girls, Araksia, dies at a young age. Armenia and the six sons remain: Garabed, Bartev, Parsegh, Krikor, Nshan and Armen.

Only the last of these six children, Armen, names his son after his father.

Philip Topdjian Jr. now lives in Spain with his family.

Armen is mentioned in the "Revolutionary Album" [1] as a terrorist who was supposed to target a Turkish governor visiting Aleppo, but the 1909 massacre of Armenians in Cilicia, organized by the Young Turks, terrified the Aleppo Armenians. Community leaders contemplated taking self-defense measures. Dikran Dzamhour, who came to Aleppo from Egypt, taught Armen how to make bombs.

When the benevolent governor of Aleppo decisively prevents the possible massacre of the Aleppo Armenians, Armen is instructed to move the fifteen bombs buried in one corner of their shop.

Despite his older brothers' urging to leave them where they are, Armen thinks of disassembling them. One of the bombs explodes while he’s doing so, He loses both eyes, one of his hands, and all but two fingers of the other. Armen was nineteen at the time.

Despite the pleas of the girl he loves, Armen refuses to marry her, saying, "Go and live your life in peace." Armen Topdjian, in his senior years, marries a young woman named Alice Keoshgerian and has one son, Philip Jr.

Garabed was a pharmacist in the Ottoman Army and worked in Baghdad. He dies there under mysterious conditions.

Krikor and his two brothers founded the Topdjian company that provided electricity and water to Aleppo. Krikor traveled to Europe to bring back heavy equipment - agricultural (like combine harvesters). The company also imported bicycles, stoves and other items.

Krikor had just turned thirty-five when he died in a fiery car crash.

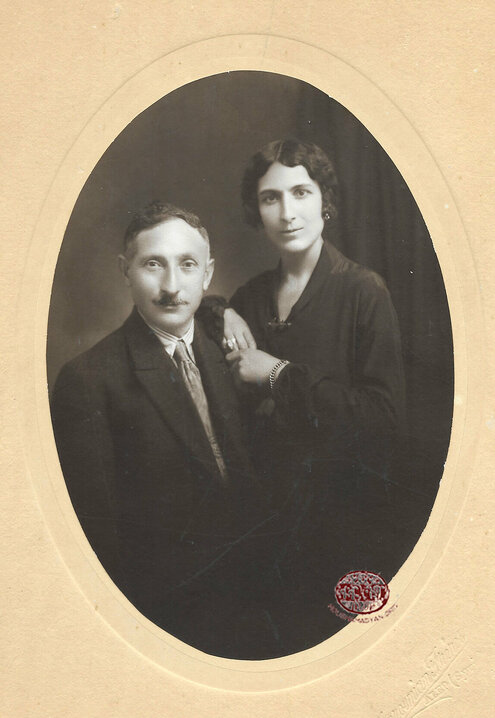

Krikor, my maternal grandfather, was married to Khanum Kasparian, whose mother, Anna Taptapian, was the only sister of the seven brothers from Ourfa, and whose father was Hagop Efendi Kasparian.

When Hagop wanted Anna as his wife, the parents and brothers refused, saying that they would not send their daughter to Aleppo as a bride. Hagop Kasparian closes his workshop in Aleppo, goes to Ourfa, and starts a new business there. He gets a house (whether he buys it or rents it, it is not clear) and again asks for Anna’s hand in marriage.

Now, there was no reason for the family to refuse. They relent and marry Anna off to Hagop.

After living in Ourfa for a year, Hagop "sells and changes" [2] everything and returns to his beloved Aleppo.

When Krikor decides to marry Khanum, he says:

- Such a beautiful girl does not deserve the name of Khanum at all. I will call you Zvart because you have a very smiling face.

It was always Zvart for us. Our grandmother with the cheery, dimpled face.

Zvart had an older sister, named Zekiyeh, but her husband never thought of changing it. It remained khaleh Zekiyeh until the end.

Zvart and Zekiyeh had two brothers, Armen and Yervant.

The five children of Zvart and Krikor were Azniv, Nazeli, Anjel, Noubar and Arousyag. Just as the Topdjians, in their day, were important personalities in Aleppo, at least three of Krikor Topdjian's children also played an important role in the Aleppo Armenian community.

Noubar, the only boy, the fourth of five children, was one of the two young doctors in Aleppo in those days, to whom at least half of the entire population of Aleppo turned to for medical assistance.

The third child, Anjel, fell under the influence of nuns from an early age, since she attended the Armenian Sisters' School of the Immaculate Conception. She decides to become a nun and is baptized Sister Melanie Topdjian. She becomes the Mother Superior in the Immaculate Conception Order and served in various cities – Aleppo, Beirut, Rome, Baghdad, Kamishli. She passes away at the Armenian Catholic Monastery in Bzommar, Lebanon.

The youngest of Krikor Topdjian's children, my mother Arousyag Topdjian-Kazandjian, studied midwifery and graduated from the French University (Université Saint-Joseph) of Beirut. Her brother, Noubar, studied medicine at the same university in Beirut. Arousyag served as midwife, and then director, at the Verjin Gulbenkian Maternity Hospital in Aleppo for fifty years.

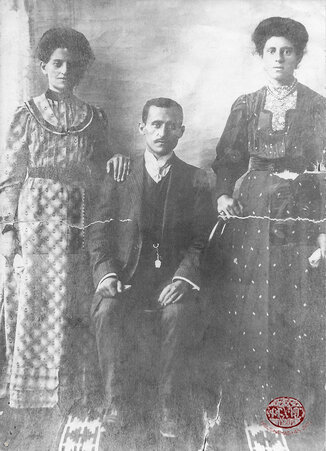

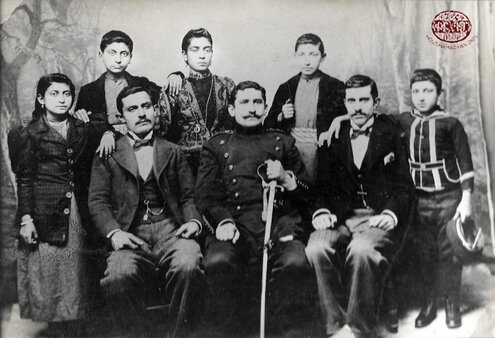

Topdjian and Kazandjian families visiting the Sebil Gardens near Aleppo. The gardens were leased by the Topdjian brothers from the government. The year is not recorded, but assuming my mother's age, it must be between 1923 and 1924. The man, wearing a fez, standing on the left side of the photo, is my father, Hovhannes Kazandjian. The person standing next to him is unknown. The man next to him, standing, is my maternal grandfather, Krikor Topdjian. He’s embracing my mother, Arousiag Topdjian. Two other persons wearing fezzes, in front of them, are playing backgammon. In the right side of the photo, the first of the girls standing in a circle dance position is Nazeli Topdjian (later Ekmekdji), the second of Krikor Topdjian's children. Next to her is Krikor’s first child, Azniv Topdjian (later Paloulian). The rest are unknown.

When my father married my mother, during the bride and mother-in-law conversations, it was revealed that the two families, the Kazandjians and the Topdjians, had been neighbors.

"I learnt more than half of my family tales from my mother-in-law, not my mother," my mother would say, and then add, laughing, that when my father's mother, my grandmother Hayganoush, suddenly realized that in an old photo my mother and father were seen at the same time, she took the photo away and my mother found it only after my grandmother had died.

Why? Because in the picture, my father, who is young and wearing a fez, is watching a game of backgammon (on the left side of the photo), while my maternal grandfather, Krikor Topdjian, who is standing opposite him, is cradling my mother Arousyag. The great disparity in age between my mother and father was already apparent.

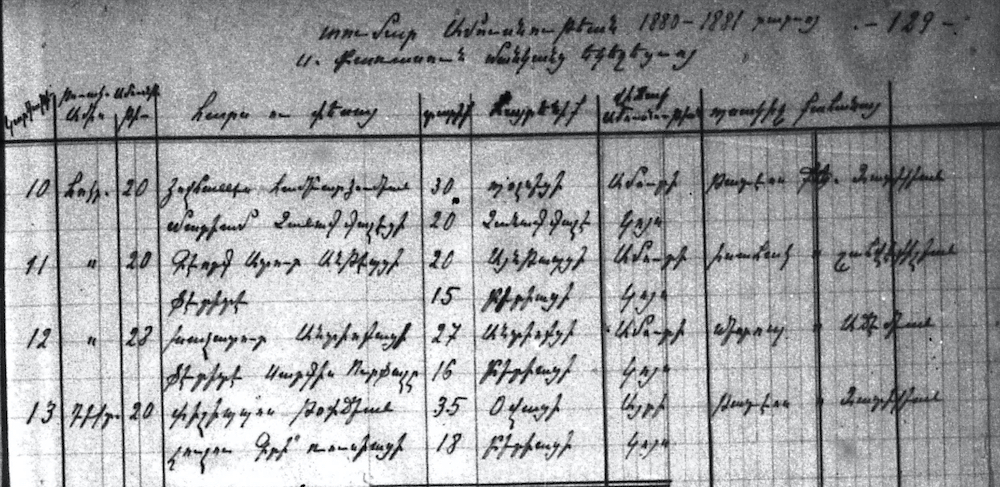

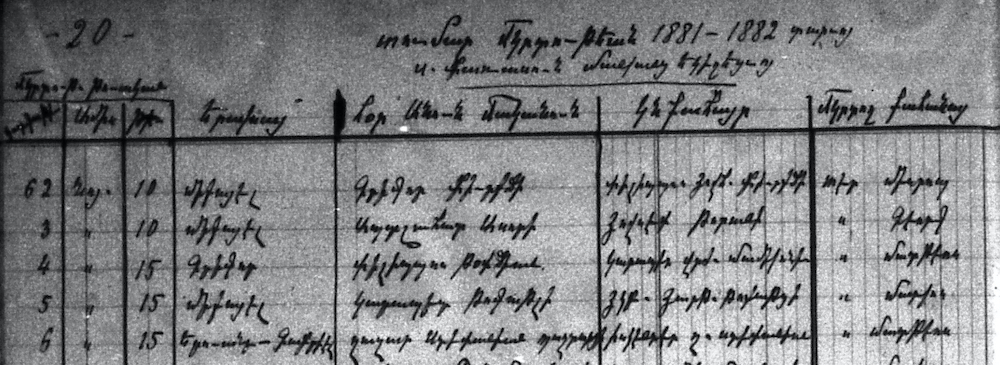

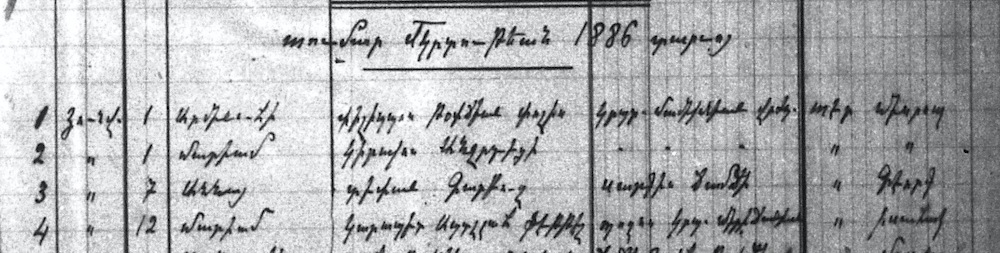

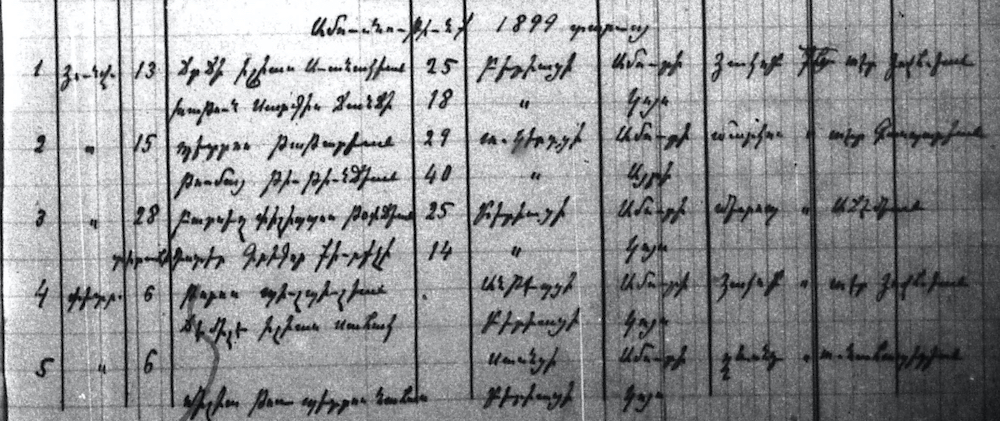

Information culled from the records of Aleppo’s St. Karasoun Manoug (Holy Forty-Martyrs) Church about the Topdjian family’s marriages and baptisms during the late 19th century (Source: Filmed by the Genealogical Society of Utah. Courtesy of George Aghjayan).

[1] "Revolutionary Album", D. Series, No. 8 (44), 1963, pp. 246-252.

[2] "Sells-changes" is in the Aleppo dialect, meaning he sold his belongings and turned it into money.