Ashekian/Iynedjian/Bakalian/Bohdjelian Coll. I

Author: Anny Bakalian, New York, 02/09/19 (Last modified 02/09/19)

Introduction

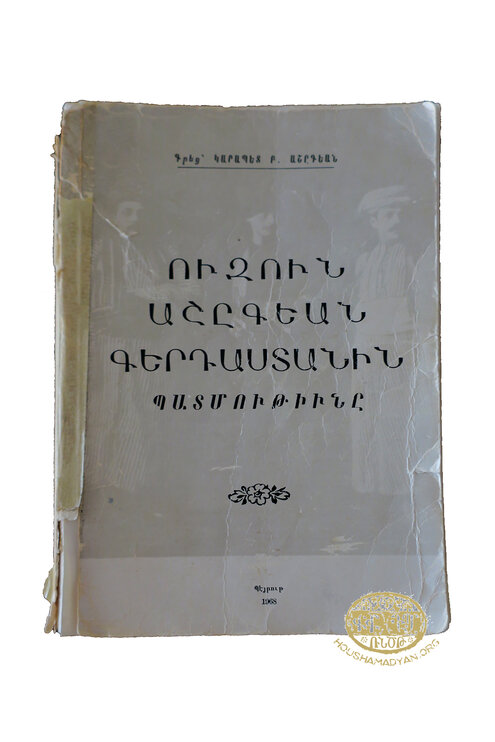

This is the story of Ashekian Clan from Kayseri/Gesaria, their patriarch, Parsegh Uzun Ashekian, and his khenamie (in-law, խնամի) Harutiun Iynedjian and their descendants from the turn of the 19th Century to the mid-20th Century. It is based on a book by Garabed P. Ashekian Ուզուն Աշըգեան Գերդաստանին Պատմութիւնը [English: Garabed P. Ashekian, The History of Uzun Ashekian Clan, Beirut: Donikian Press, 1968. Translated into English by Vatche Ghazarian (Monterey, CA, 2013)].

According to the chronicler of the Ashekian Clan from Kayseri/Gesaria, Parsegh Uzun (tall in Turkish, referring to his height) Ashekian settled in Kayseri/Gesaria because of the persecution of the Persians in the late 18th century. Parsegh Uzun Ashekian came from the Persian Empire’s controlled territories of historical Armenia. However, the exact village or town of our Patriarch is not known, and this area is rather large.

The Qajar dynasty began its rule of Persia under Agha Mohammad Shah (1789-1797) and brought the Caucasus under their reign. During the Battle of Krtsanisi (September 1795), the Qajar army crossed the Aras/Arax River, subordinated the khans in Yerevan and captured Tbilisi and called it Khorasan. To restore Russian prestige, Catherine II (the Great) declared war on Persia, but the new Tsar Paul I, who succeeded Catherine in November 1796, shortly retracted it. Agha Mohammad Shah was later assassinated while preparing a second expedition against Georgia in 1797 in Shushi (now in Artsakh). This area also saw wars between the Persia and Russia in the early 19th century.

Seated, left to right: Nevrig (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Taniel Allahverdian (born in Kayseri/Geseria circa 1870–died Istanbul in 1967) and her husband Taniel Allahverdian was born in Kayseri and moved to Bandırma. They had four children: Hripsimé (née Taniel Allahverdian) Garabed Ayanian (born Bandırma, circa 1883-died Knoxville, TN, in 1984); Harutiun (Artin) Allahverdian (born Bandırma, circa 1884-died Yerevan); Nevart (née Taniel Allahverdian) Garabed Baltayan (born Bandırma circa 1889-died Istanbul in the 1960s); Kevork Allahverdian, after 1923 Allahverdi (born Bandırma in 1891-died Istanbul in 1970).

In Kayseri/Gesaria, the patriarch had two sons: Hadji [1] Bedros and Hadji Garabed. Parsegh may have had other children, but they are not known. The sons were merchants, who ran caravans to Iraq and Iran with Armenian and Turkish riders to bring horns of oxen and buffalos that were used for harnesses. They also lent their caravans to farmers in Cappadocia at harvest time because that increased their prices. These brothers had a total of 18 children, who would go on to make large families of their own.

Bedros Parsegh Uzun Ashekian (born in Kayseri circa 1810 and died in Kayseri circa 1890s), the elder son of the patriarch was tall as his father and handsome during his youth. He married a woman whose family name is not known; their children were Parsegh, Yeghisapet and Mariam; after his first wife died, Bedros married Mariam Merdinian; her family was prominent in Kayseri. She gave him eight children: Anna, Sdepan, Nuritsa, Hovhannes, Filor, Sima, Shemsi, and Shahmir. All together Bedros had eleven children.

The second son of the patriarch, Garabed Parsegh Uzun Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria in 1818—died in Adana on January 30, 1903) received his education in Kayseri and was able to read the Bible and calendars. In a ledger, he meticulously recorded the birth and christening of his children, the names of their godfathers, and the list of receivable and payable amounts.

Garabed married Hripsimé Murad Tekeyan; the poet Vahan Tekeyan (born Constantinople in 1878—died Cairo 1945) was her nephew. They had six sons, Parsegh, Harutiun, Dikran, Nazaret, Misak, Mihran, and the last was a daughter, Nevrig.

Mariam daughter of Bedros Uzun Ashekian married Hadji Harutiun Iynedjian (born Kayseri, circa 1825—died Constantinople, circa 1915). He was in the business of silk threads and simultaneously the chief of the Armenian quarter in Kayseri/Gesaria. Harutiun and Mariam had four daughters, Gyuldudu, Dikranuhi, Diruhi, Nevrig and three sons, Hovhannes, Nazaret, and Bedros. Thus the first intermarriage between Ashekian and Iynedjian families started the kinship of both families from Kayseri/Gesaria at the turn of the 19th century.

Seated, left to right: Marina (née Parsegh Ashekian) Bedros Ashekian, Haiguhi (née Parsegh Ashekian) Sarkis Bakalian and Tsoline (née Dikran Ashekian) Garabed Djirdjirian.

Standing, left to right: the cousins and children: Louise Mihran Ashekian, Victor (née Mihran Ashekian) Levofet Pambukdjian, Arpine (née Diran Kazandjian) Apkar Salatian, Lousadzine Dikran Ashekian, Zarouhi Dikran Ashekian, Mampile (née Sarkis Bakalian) Hagop Touryantz, Chaké (née Bedros Ashekian) Puzant Najarian, Anahid (née Diran Kazandjian) Arsen Bedrossian and Mayda Levofet M. Pambukdjian.

Front, youngest children, left to right: Sirarpie [aka Pepi] (née Bedros Stepan Ashekian) Kevork Yaghdjian, Berdj Diran Kazandjian, Vasken Sarkis Bakalian.

During World War I and the Armenian Genocide, few persons perished among the Ashekian Clan from Kayseri/Gesaria because they were well off and had strong relations with Committee for Unity and Progress (CUP) politicians. Their flourmill in Adana had strategic value, sparing many lives of mill employees. Eventually some ended up in Lebanon, while others in Romania.

Over the 19th century, the elders preferred marital partners within the clan both along patrilineal and matrilineal lines and preferably natives of Kayseri/Gesaria. A man’s responsibility was to procure for his family. Most of the men in the clan worked in commerce and invested in property until the turn of the 20th Century. The elders in the clan were like an insurance association in modern times; for example, they helped when a gifted child wanted to further his education or needed an apprenticeship, provided young men seed money for a venture, and helped the widows and orphans of the family.

The women were in control of the house; raised children, and took of care of the sick and elderly. They were responsible to produce food—cooking, baking, and most importantly prepare for the winter; they preserved vegetables, fruits, herbs, and animal products. Armenians call this endeavor bashar (պաշար, in Arabic mouneh and Turkish in karşılık). Many other activities such as sewing, knitting, making clothing and bedding, washing, keeping the home clean and safe were women’s work. They also sought that their home was attractive with their embroidery, crochet and tatting skills. Furthermore, the women learned from their mothers and aunts home remedies to cure and heal the sick and mend injuries: cupping to ease cold symptoms, drinking quinces seed tea for coughs, swatting iodine for sore throats, and homemade eyewash to heal styes. After the mid-20th century, these essential practices moved to manufactories, relieving women of most of their chores.

Thus, the elders of the Ashekian, Allahverdian, Ayanian, Bakalian, Baltayan, Boghossian, Bohdjelian, Kazandjian, Iynedjian, Ohanian, Ourfalian, Pambukjian, Salatian families … functioned as a corporation and/or government. Many survived the Genocide, World War I, the Soviet regime, and other wars and economic crises because their networks supported each other. Finally, by the 21st century these families caught up with modern family patterns. Today, financial assistance and business partnerships is much less common and marriage among kin is almost taboo. Instead, sentimental feelings keep relatives attached through funerals, weddings, Christmas messages and visits.

Four POSTs will tell the stories of these families with text, photos, images of objects and family trees from the 19th century to the mid-20th.

Seated, left to right: 1-3 not known, 4th Mr. Mansorian, 5th Voskan Bey Mardinian, 6th Sarkis Bakalian, 7th not known (possible Mr. Tateossian/Thaddeus), 8th lady shows in many of Haiguhi’s photos, her name not known.

Standing behind the chairs, left to right: 1-6 not know, 7th Mrs. Maritza Tateossian/Thaddeus from Baghdad, 8th Haiguhi Bakalian, 9th Pakrat Bakalian, rest not known.

Standing at top, left to right: Not known except Meroujan Shahinian on the right in black suit.

Sitting on ground the children, left to right: 1st and 2nd children not known, 3rd Benjamin Thaddeus, 4th not known, 5th Lila Thaddeus, 6th Vasken Bakalian, 7th, Mampile Bakalian, 8th in the lap of a lady sitting Jacob Thaddeus, others not known.

POST I: The Descendants of Parsegh Ashekian from Kayseri/Gesaria who settled in Lebanon

Post I introduces descendants of Garabed Ashekian, the son of Parsegh, the Patriarch through personal and professional stories and photos. As Adana had better commercial opportunities than Kayseri, the eldest son of Garabed settled there, and his five brothers and sister followed him. Dikran Ashekian and Sarkis Bakalian, brothers-in-law, bought an electric flourmill in Adana in 1908, which was a fundamental decision. The majority of the men who were affiliated to the mill were exempt from military service and the old and young were not deported because the factory served the military authorities during World War I. Members of the Ashekian Clan used their connections with the government and their wealth to survive unlike many Armenians that were exiled to the desert and died.

By 1920, the descendants of Garabed Ashekian moved to Cyprus and then settled in Lebanon. Sarkis Bakalian built his flourmill in Beirut. The Ashekians sent their children to universities and they became professionals. They learned Arabic, French, English, but continued speaking Armenian and Turkish. Until the Lebanon Civil War (1975-1990), the fifth generation had also engaged in Armenian and Lebanese business, politics, and cultural life.

POST II: The Descendants of Harutiun Iynedjian of Kayseri/Gesaria who passed through Constantinople and those who stayed in Istanbul

Post II presents the family of Harutiun Iynedjian (in-laws to the Ashekians) that lived in Constantinople and those who passed through the city. It focuses on how the life of Armenians changed in times since the Treaty of Lausanne (24 July 1923), which acknowledged the “Republic of Turkey.” Soon after, Ankara was proclaimed the capital (13 October) and Mustafa Kemal became the First President. It was a glorious year for the Turks and an apprehensive time for Armenians and other minorities. Radical reforms followed such as the centralization of education in 1924; the banning of headgear like the Fez in 1925; the introduction of the international time zone system and Gregorian calendar in 1925; the Vatandaş Türkçe konuş! [Citizen, speak Turkish!] Campaign in 1928; the renaming of Constantinople to Istanbul in 1930; the Surname Law of 1934; and the adoption of a new Turkish alphabet in 1928. An Armenian, Hagop Martayan, created the new script, but Mustafa Kemal renamed him Dilacar. All of this was punitive action against Armenians. Besides personal changes there were changes in geographical names (such town/village, street, lake, and mountain) that were Armenian, Assyrian, Greek and Kurdish were changed into Turkish.

From left: Sarkis Keldjian (born 1898 in Constantinople), next is his mother, the girl not known, Arousiag Keldjian (1886-1970), in her lap is Sona (née Kevork Allahverdi) Bakalian (born Istanbul 1922-died New York 2006), the next lady is Sona’s grandmother’s sister, Kohar (née Keldjian) Allahverdi (1893-1997), Kevork’s mother Nevrig (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Taniel Allahverdian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria circa 1870–died Istanbul 1967) and Kevork Allahverdian/after 1923 Allahverdi (born Bandırma in 1891-died Istanbul in 1970).

Included among the relatives who moved to Constantinople were the daughters of Harutiun Iynedjian—Dikranuhi, Nevrig, and their youngest brother Bedros. Bedros Iynedjian’s wife, Pérouze, had Tuberculosis; he took his family to Lausanne (Switzerland). Until now, B. Iynedjian Tapis D’Orient is on Rue de Bourg. Kevork Allahverdian/Allahverdi, son of Nevrig lived most of his life in Constantinople/Istanbul except during World War I. His daughter, Sona (née Allahverdi) Bakalian, was a citizen of the Republic of Turkey, until she moved to Lebanon.

POST III: The Descendants of the Ashekian Clan from Kayseri/Gesaria who settled in Romania

Post III focuses mostly on the families that settled in Romania from 1900 to 1950s. As early as 1896, Avedis and Armenag Bohdjelian, the sons of Gyuldudu (née Iynedjian) Bohdjelian settled in Romania. After World War I, many more relatives settled there, for example, Garabed Ashekian who wrote, The History of Uzun Ashekian Clan, and his family. In 1947, the Socialist Republic of Romania became part of the Soviet Bloc. The centralized system ruled by the Communist Party made the lives of the citizens miserable. Consumer goods, including food, clothing, shoes and housing, were not produced sufficiently and were not distributed equally. Further, personal properties such as houses, shops and factories were confiscated; some persons were accused of hiding gold or acting bourgeois, therefore sentenced to several years of prison. Eventually, almost all the clan families left Romania via Beirut to process their visa to the U.S.A. Thanks to ANCHA (The American National Committee to Aid Homeless Armenians) these families first went to Beirut for a year or two to receive their visa to North America. While some settled in Philadelphia, Los Angeles, New York, Baruir Garabed Ashekian went to Montreal, Canada.

1. 1927 c. Avedis Bohdjelian with his wife Rosiga, son Berdj and Rosiga's sister at the beach, Black Sea.

2. 1934 c. Picnic in Romania with the descendants of Parsegh Ashekian.

Standing, left to right: Local woman, maybe the help; Garabed Ashekian; Aram Bohdjelian; Stepan Hampartsum Allahverdian; Harutiun (Artin) Allahverdian.

First Seated, left to right: Berjouhi (née Bagdasar Hovagimian) Ashekian; Mannik (née Bohdjelian) Allahverdian; Diruhi Ashekian (wearing a black scarf); Armenag Bohdjelian; Bedrig Bohdjelian; Gyuldudu (née Iynedjian) Bohdjelian.

Second Seated, left to right: Garbis Karekin Ayanian; Louise Allahverdian; Marie (née Dilsizian) Allahverdian; Hripsimé (aka Sima) (née Allahverdian) Ayanian; Karekin Ayanian; Hermine is between her mother and father.

On the Ground: Elena Harutiun

POST IV: The Descendants of Bedros Parsegh Ashekian

This post follows the descendants of Bedros Ashekian, the son of the Patriarch Parsegh who settled in Kayseri/Gesaria at the turn of the 19th century. Bedros had eleven offspring; some are mentioned in Post I, II and III because of the kinship between the Ashekian and Iynedjian families. For example, Mariam, the wife of Harutiun Iynedjian’s four daughters—Gyuldudu who went to Romania, Dikranuhi went to Constantinople, Diruhi to Romania and then to Lebanon, Nevrig lived in Istanbul—and two sons—Hovhannes who settled in Romania and Bedros in Switzerland. Bedros Ashekian the grandson of Bedros, son of the patriarch, who established in Lebanon with his wife Marina and daughters Chaké and Sirarpie. Bedros' sister, Azniv (née Ashekian) Bouldoukian had a son, Vahé, was a famous photographer in Beirut.

We depend on Garabed Ashekian’s book to trace the descendants who settled in Egypt, Iraq, Palestine, Syria, England, Buenos Aires and the United States of America.

Thanks to Houshamadyan, these posts will show future generations whether they are the descendants of the Ashekian Clan of Kayseri/Gesaria or not, the life of an Armenian family and its descendants during the Ottoman Empire and after the Genocide until the middle of the 20th Century.

Please contact Houshamadyan if one identifies a “lost” kin!