Hovhannes Haroutyunian Collection - Aleppo

The Garden of Gladioli

Author: Maroush Yeramian, 09/11/20 (Last modified 09/11/20) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

Is there a more appropriate repository of memories than Houshamadyan?

Is there a more appropriate site to publish an article about an Armenian gardener? Houshamadyan, whose pages tell the poignant story of Western Armenians; whose articles elicit grief and sadness, because they speak of loss and pain…

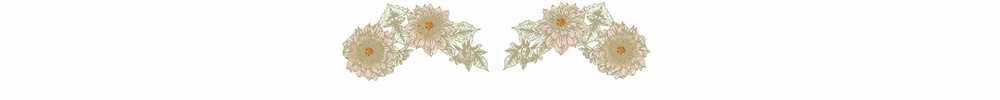

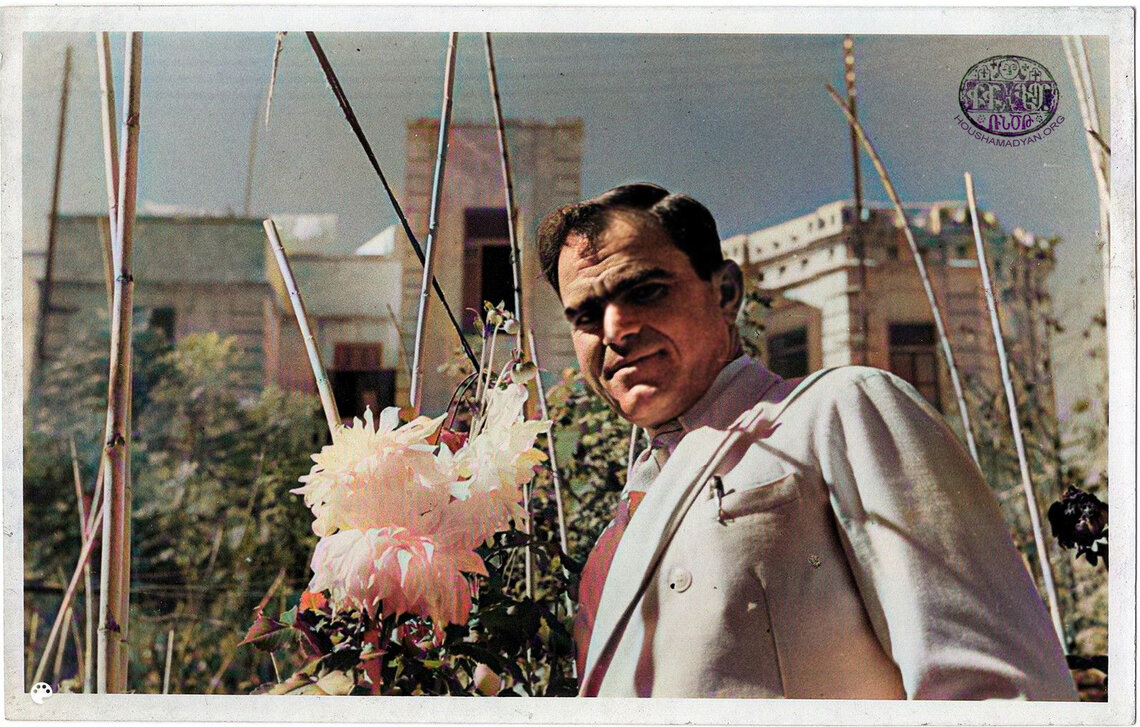

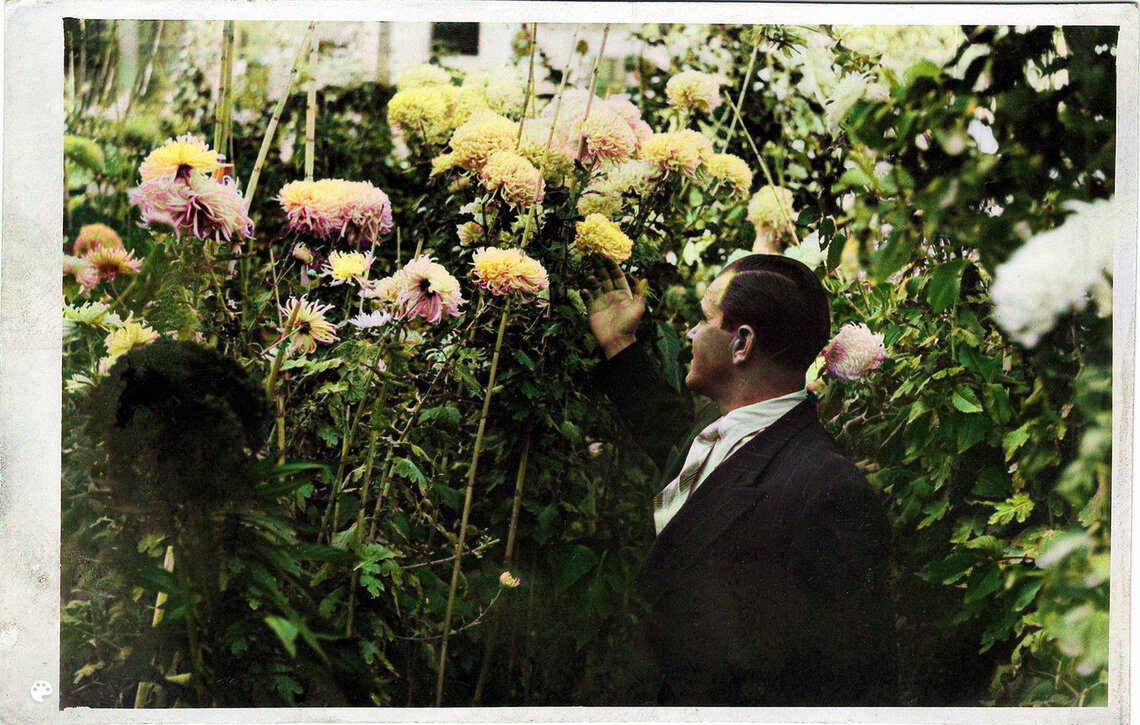

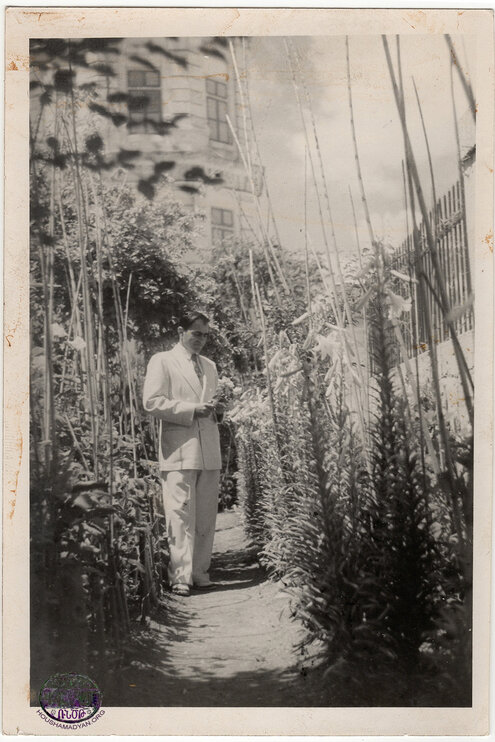

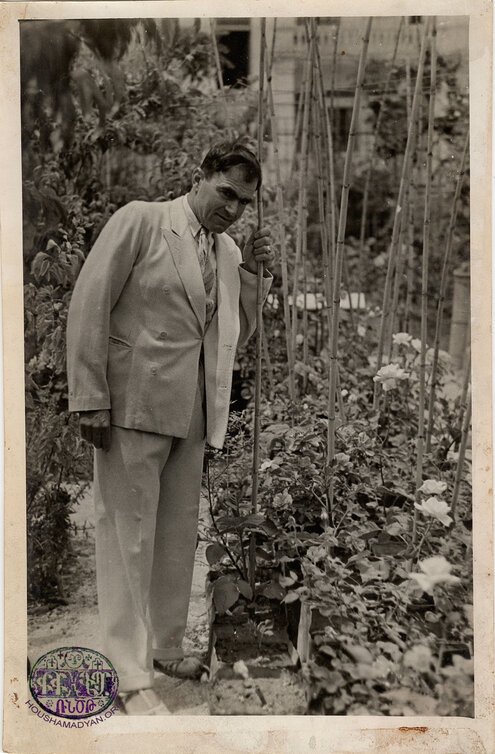

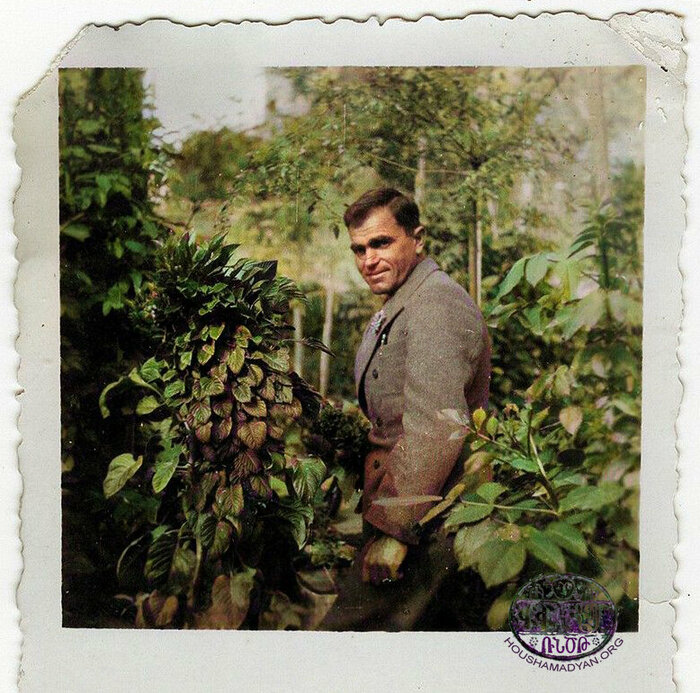

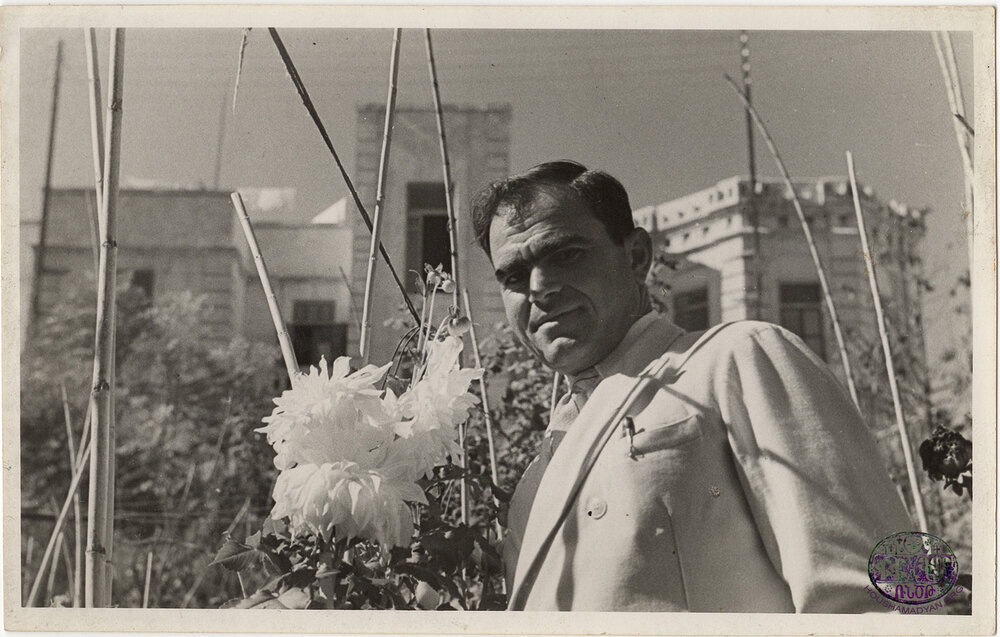

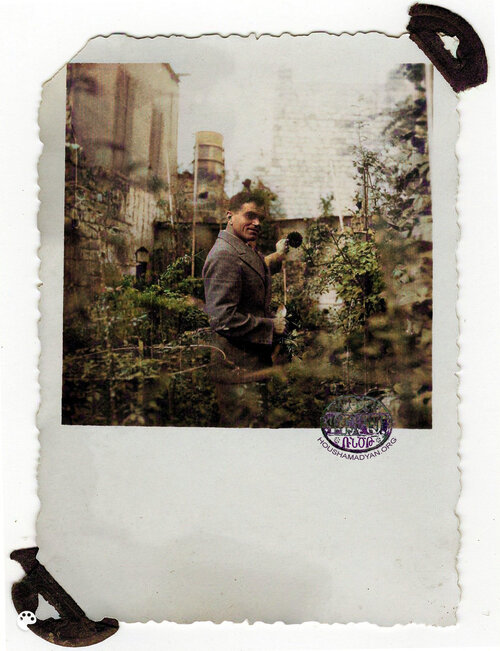

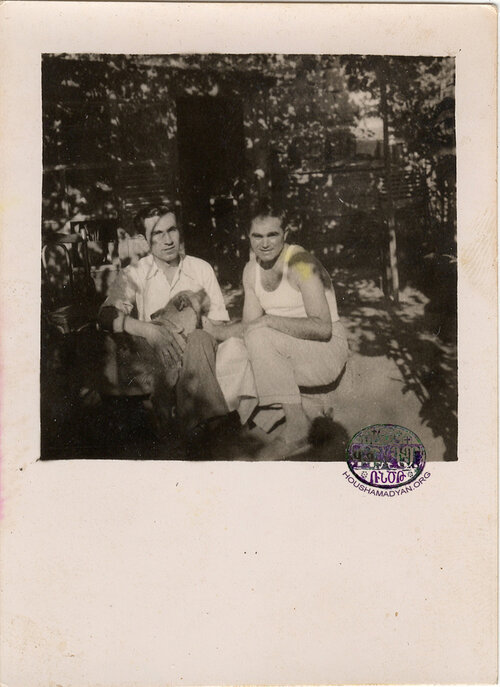

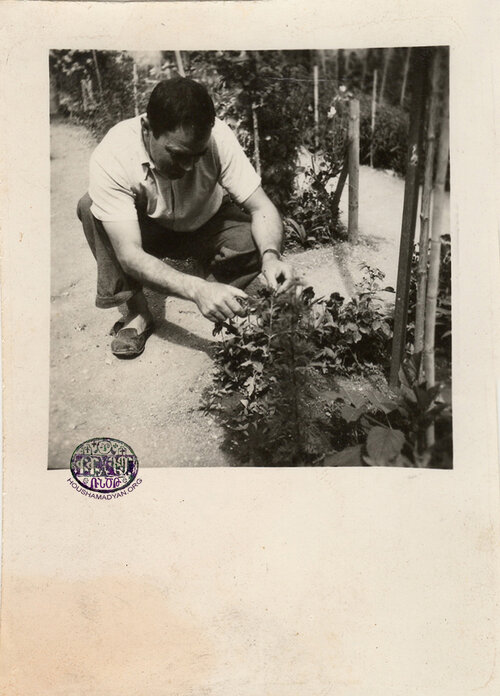

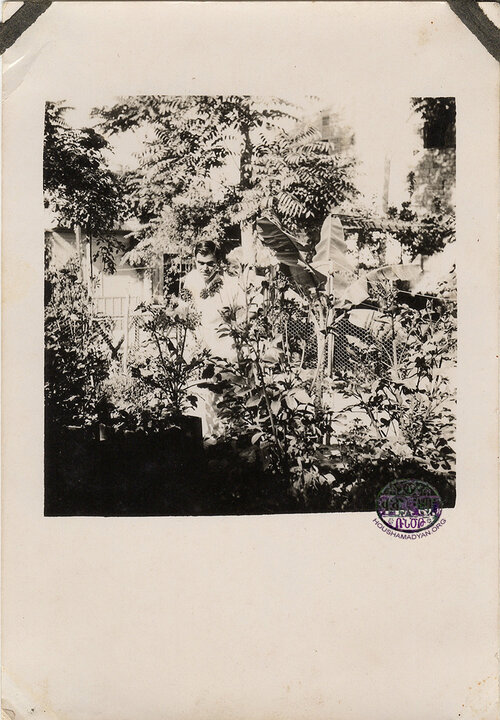

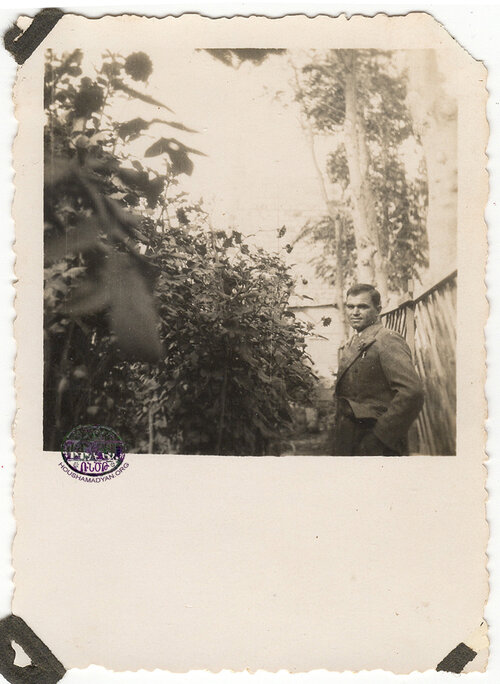

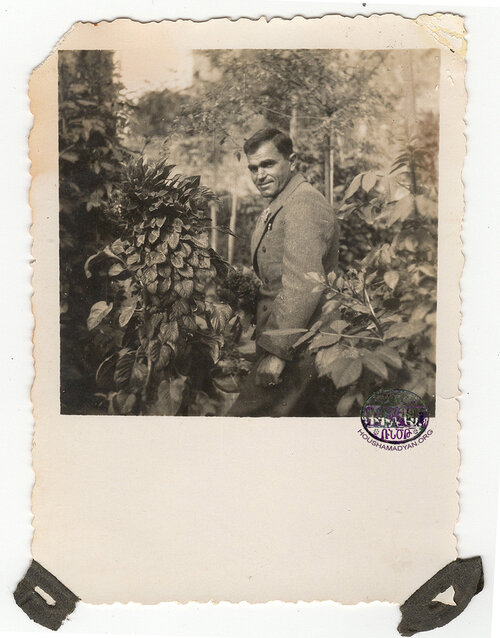

Hovhannes Haroutyunian.

A gardener and an expert grower of flowers.

One Thousand and One Roses…

Perhaps the small piece of land he owned was born of the dim memory of one thousand and one churches. Alongside the flowers that grew on it, it was the distant and fading reverberation of the silenced and disused church bells of Armenia. Perhaps, for Hovhannes Haroutyunian, his small garden was a memorial for his parents and for all the martyrs. He probably never had these thoughts. Simply, instead of lighting candles, he grew flowers. He had grafted new ones, blood red, white, and of all other colors of the rainbow. In his store, One Thousand and One Roses, he had probably grown half a million flowers by the time he was of old age. He continued living on his small plot of land and in his small house, surrounded by his flowers.

Today, the One Thousand and One Roses store still stands in Aleppo, in the corner of that same plot of land. But it is in ruins, and only grass grows there.

Even my son remembers “that lot and the small store in the corner.”

History lives in people’s memories. In some mysterious way, the ruins of One Thousand and One Roses become intertwined with the ruins of our one thousand and one churches.

***

I never thought that one day, I would open this small window into my memories, or that I would be compelled to remember One Thousand and One Roses.

We would walk from our home to Mushiye. From there, we would ride the public bus, which would take us to my aunt’s home in the Muhafaza district.

It was unusual for the Armenians of Aleppo to live outside the Christian neighborhoods of the city, which were Nor Kyugh, Soulemanieh, and Azizieh.

But wealthy Christian Arabs had started buying houses in the suburbs, building multi-story buildings and moving to these slightly elevated areas. They were drawn there by the promise of tranquility and clean air.

On our way to Mushiye, we would pass a store with dirty windows, abutting a garden. The garden was almost entirely obscured by tall grass. One day, when I was a child, I ran off from my mother and turned the corner, trying to see what was on the other side of the fence. But still, I only saw grass.

My girlish imagination conjured great wonders behind the screen of grass. Perhaps a palace where a princess lived, a princess searching for a friend, for a playmate. Of course, in my imagination, the princess was bound to be of the same age as I, or perhaps a few years older.

Then, one day, behind the dirty windows, I saw bouquets of flowers. These were so different from the carnations I knew. They had long stems and elegant petals. I let go of my mother’s hand and went to stare into the window, hypnotized.

I would later see such flowers in the hands of brides, rolled in transparent paper, tied with ribbons, bereft of their beauty. The gladioli arranged in the shop were much lovelier.

The store had no name. Or at least, I didn’t know what it was called, until one day I overheard a conversation between my mother and my aunt:

“You walk past the One Thousand and One, you cross the street, then you turn right.”

“The One Thousand and One?” I asked, forgetting that I was not supposed to interrupt conversations between adults.

“The One Thousand and One Roses. The flower store…”

At that point, seeing that I was brazenly eavesdropping on the conversation, my mother ordered me to go to my room.

In the solitude of my room, my imagination took flight and I believed more than ever that a princess lived in that secret garden…

Years passed, and I learned that the owner of the One Thousand and One Roses was Armenian, a boy who had been orphaned during the Genocide and had made it to Aleppo. He had been only five years old during the massacres.

In my imagination, the princess transformed into a sad boy who loved flowers so very much.

Other Armenian survivors had buried themselves in their daily grind. Some had even completely abandoned their Armenian identities. They had done so just to go on living with the memories of what they had witnessed – memories that stubbornly refused to become mere remembrances.

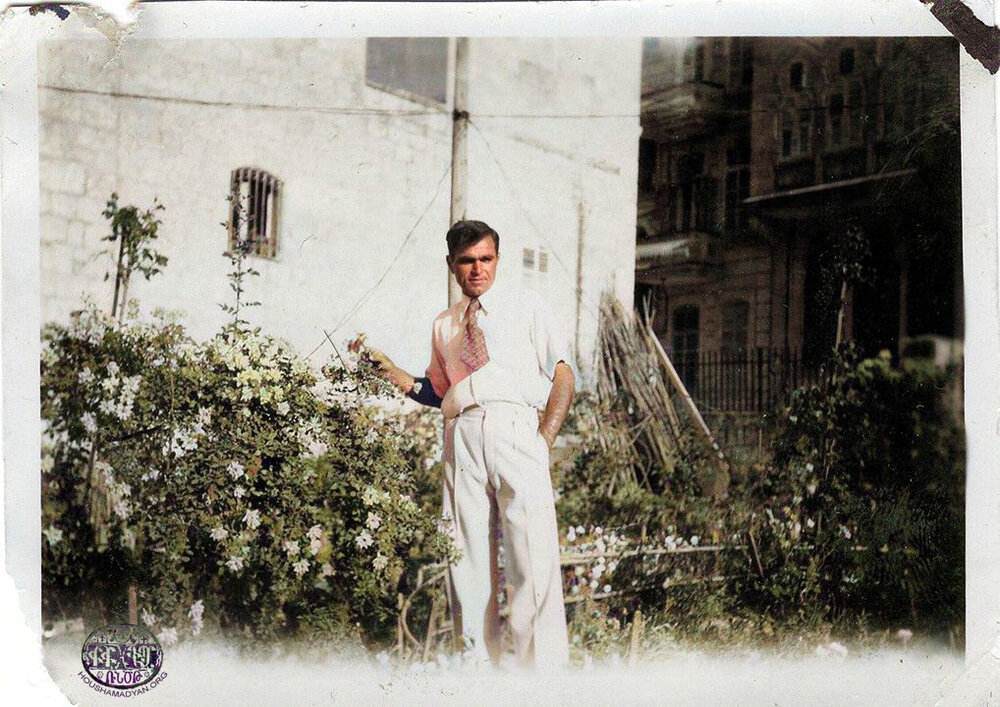

As for Hovhannes Haroutyunian, he had dedicated himself to growing flowers on that small plot of land, which was both his home and his place of work.

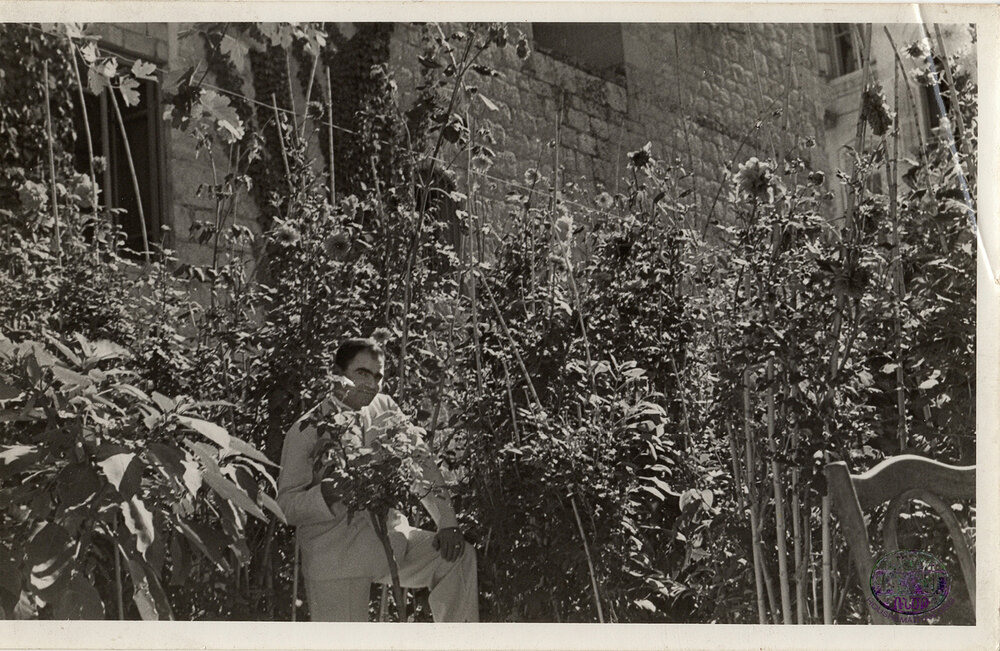

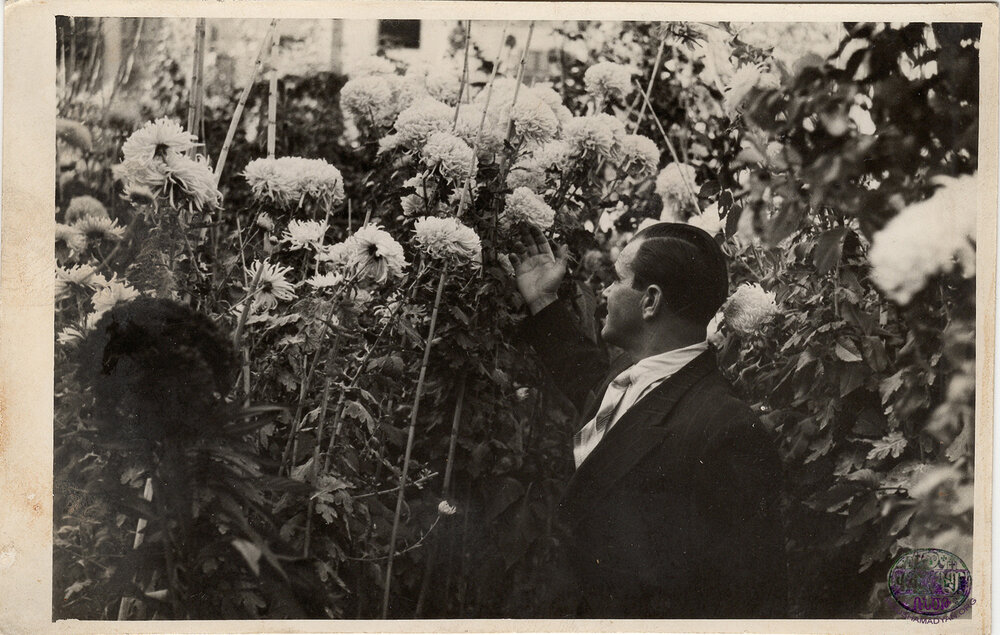

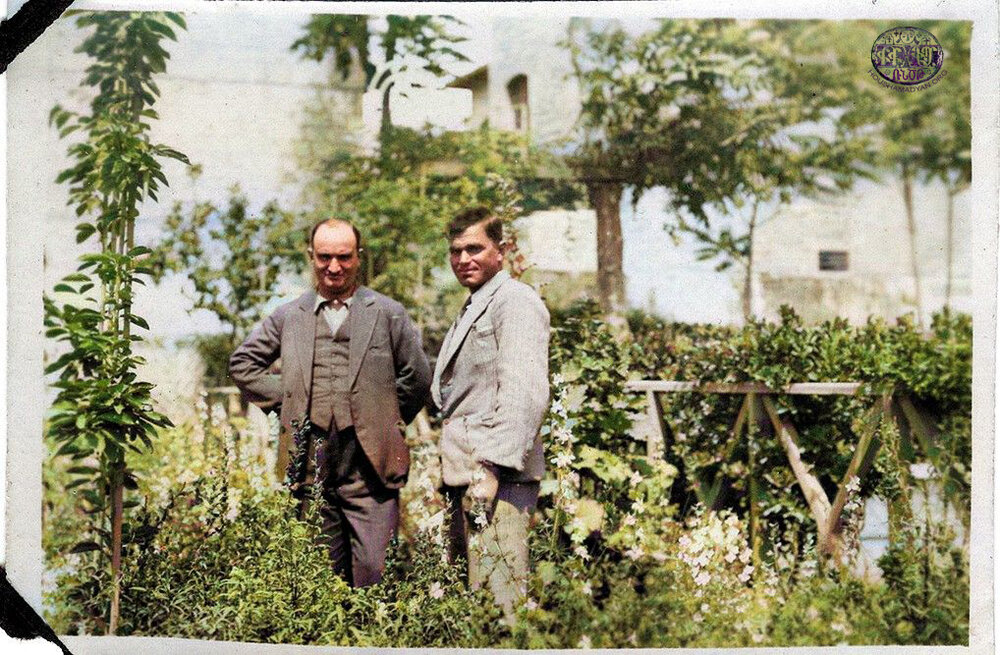

He was the first flower grower and florist in Aleppo, which, at the time, was an important but still provincial city. Alongside carnations, he was the first in the city to grow gladioli and dahlias (the dahlias he grew can be seen in the photographs).

It is not clear how he was able to obtain such a choice plot of land in the city’s best neighborhood (even today, Azizieh is considered to be almost the only ancient and upper-class district of Aleppo). Perhaps, like many other orphans who had reached the city after the Genocide, he had learned a craft and had been able to purchase the land with the money he had earned.

Land…

For the boy from Dörtyol, land was important, just like the land on which, in his childhood, his mother had grown flowers alongside vegetables. Every morning, little Hovhannes would awaken to the fragrance of these flowers that filled the air when his mother watered them…

Later, the boy who had survived the Genocide alone was adopted by a Kurdish family. He had stayed with them until his adolescence, until his young legs were strong enough to carry him to Aleppo.

Was it gratitude or simple humanitarianism that prompted him, until the end of his life, to do whatever he could to help the Kurdish people? It was probably gratitude, but he was certainly a humanitarian, because Hovhannes, the lover of flowers, was undoubtedly a lover of humanity.

In Aleppo, he had found his sister, Lousaper, whom he had lost during the deportations.

Lousaper re-married in Aleppo, to Sinan Balian (this was also Sinan’s second marriage). They had four children – Haroutyun (born in 1924), Ardemis (born in 1924?), Bertha (born in 1927), and Mary (born in 1929). Lousaper and her family lived in Beylan until 1939.

Haroutyun’s sister’s family also became his, he who had lost his parents at a young age and had not been able to start a family of his own.

He died in the 1990s.

In addition to the remembrances of One Thousand and One Roses that live on in the memories of many, Hovhannes Haroutyunian also left behind this bouquet of photographs. By some strange magic, the fragrance of his flowers reaches the nostrils of everyone who sees them.

Cairo, September 2020

* The photographs on this page were originally in black and white. They were digitally colorized using DeOldify and retouched by Houshamadyan.