Armenian Refugee Camps in Damascus from the 1920s

Author: Sevan Boghos Der Bedrosian, 18/03/22 (Last modified 18/03/22) – Translator: Simon Beugekian

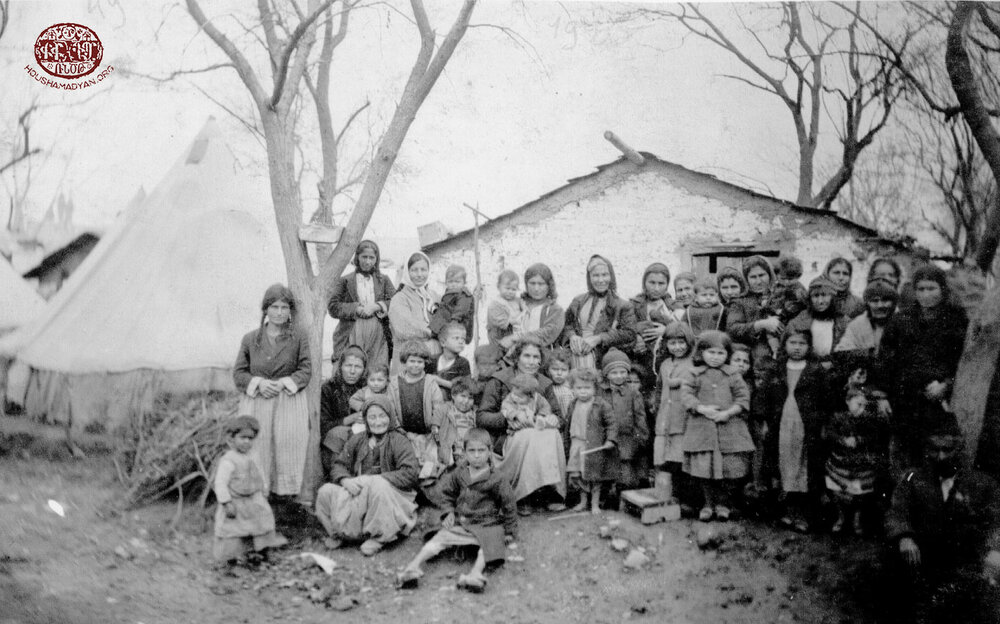

The refugee camps that provided shelter to the survivors of the Armenian Genocide were a critical and important stage in the life and future development of surviving Armenian communities.

This article explores the history of Armenian refugee camps (usually known simply as “camps”) in Damascus, which were established beginning in late 1921, after the arrival, en masse, of Armenians to Syria and Lebanon. This post-Genocide wave of migration began when French forces withdrew from Cilicia and the entire region was once again annexed by Turkey. On the eve of the entry of Turkish forces into the area, a wave of mass migration of Armenians began, mostly towards Syria and Lebanon. Most of these refugees initially settled down in refugee camps that had been hastily erected in the large cities of the Levant, including Aleppo, Beirut, Damascus, and Iskenderun (Alexandretta).

It was imperative for the French Mandate authorities of Syria and Lebanon to resettle these refugees. In other words, their aim was to move the refugees out of temporary camps and into permanent homes in residential neighborhoods. And so, in 1926, the resettlement efforts of various disparate organizations were brought together under a single aegis. Among the organizations spearheading these efforts were the League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the French Mandate authorities, the Syrian and Lebanese authorities, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU). These efforts were coordinated by the League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, also known as the “Nansen Office”; and its representative, the Swiss Georges Burnier.

Armenian refugees had mainly settled down in two different areas of Damascus. First, there were the camps that had been erected outside the city walls, and which were soon converted into permanent Armenian neighborhoods. A second group of refugees had sought shelter within the city walls, where they lived in homes rented from local Arabs and in rooms rented in local inns.

Camps Established outside the Damascus City Walls (Extra Muros Camps)

The al-Kadam Camp

A group of Armenian refugees found shelter in an old, abandoned Ottoman Army barracks near the al-Kadam train station. But these refugees were soon moved to the mostly Christian-populated neighborhoods of Damascus, and as a result, this camp had a short life.

Camp Dikran (or Bab Sharki Camp)

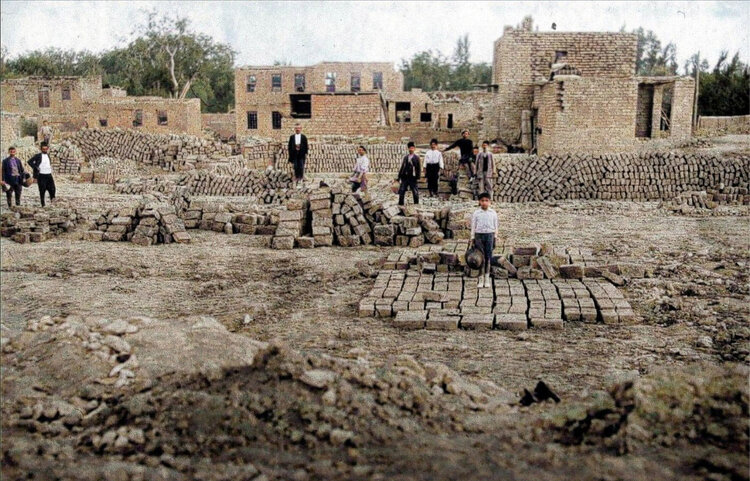

Another group of refugees settled down right outside the Bab Sharki [Eastern Wall/Gate] area of Damascus, to the south of the city. For many years, the site had been a glass factory. The refugees initially erected tents and other temporary structures made of tin. Soon, however, they began building more permanent structures. This camp was known both as Camp Dikran and as the Bab Sharki Camp.

In the second half of the 1920s, the project to close the Armenian refugee camps and resettle refugees in residential neighborhoods was initiated. In the case of Camp Dikran, the plan called for the refugees to remain at the same site; and to build permanent, safe homes to replace their improvised shelters. Many of these homes still stand today.

Once the plans for construction were finalized, Georges Burnier, the representative of the “Nansen Office,” supervised the work on the ground. The refugees did not have the ability to pay for their new homes, so each homeowner signed a contract with the “Nansen Office,” stipulating that they would repay the office the costs of construction over the following seven years, after which they would officially become the owners of their own homes.

As the financial situation of the refugees improved, they purchased additional land in the same area and built new homes. As a result, the camp began expanding and its population gradually grew.

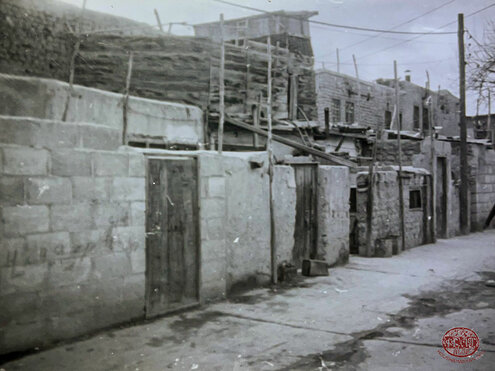

The homes built in Camp Dikran were identical. They each had two stories, each story with a total size of seven-by-five square meters. The main materials used in their construction were cob, wood, and clay. The ceilings and roofs were reinforced with logs of wood. These homes were considered sanitary, as they had windows that allowed a generous amount of sunlight to penetrate, and were located on the two sides of a wide road. Moreover, each home had its own toilet and bath. The only significant challenge was the provision of water to the homes. Water had to be carried to the camp on foot from the wellspring near Bab Sharki, located about 500 meters away.

The workshops of the residents were not located inside the camp. They would work in the other districts of the city. But among the shops and shop owners inside the camp were Dikran’s bakery, Bakkal (grocer) Levon, and Bakkal Noubar. A significant percentage of the population of this camp consisted of refugees from Hadjin.

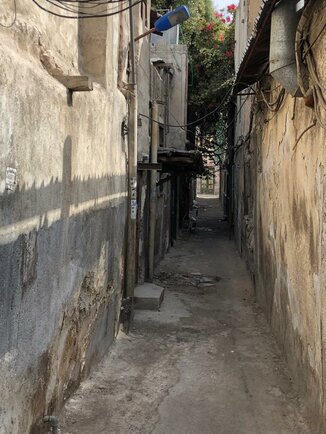

Camp Dikran is unique in that it has retained much of its original form into the present day. Only two or three Armenian families still live there. But to this day, the area is called “the Armenian Neighborhood” (حي الأرمن), and the homes built by the Armenian refugees still stand.

Khcheri Camp (Khcher’s Camp)

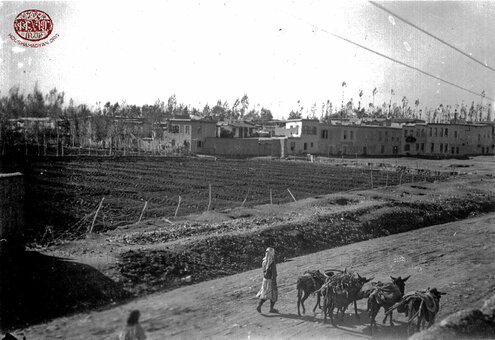

An Armenian refugee camp was built in the Zablatan area of Damascus, where refugees lived under tents. Soon after their arrival, these refugees began building simple huts with cob and wood, with roofs made of tin. In 1924, new refugees streamed in from Cilicia, including Khcher Geondjian, from Adana. He settled down in the Zablatan area, where he rented a home for himself and his family. When he began inquiring into renting more accommodations for his relatives and friends, he realized that it was cheaper to build a new hut (five pounds) as opposed to renting one for a year (14 pounds). Khcher came to an agreement with his Arab neighbor, and built huts on the latter’s land, renting them out for three pounds per year to Armenian refugees. The number of huts soon reached 100, and the number of residents reached 1,300.

This is how the Zablatan refugee camp came to be known as the Khcher's Camp. In the early years of its existence, the local Arab population simply called it the “Armenian Camp” (كم الأرمن). In the local vernacular, the word “camp,” transliterated into Arabic, had lost its last consonant sound, resulting in the appellation “Kumm el Arman.”

The camp was located east of the Burj al-Rous square of the city, west of the Zablatan Corniche, south of the al-Salib (Holy Cross) Church, and north of Boutros al-Boustani Road. The area of the camp is known today as Haret al-Salib (Neighborhood of the Cross).

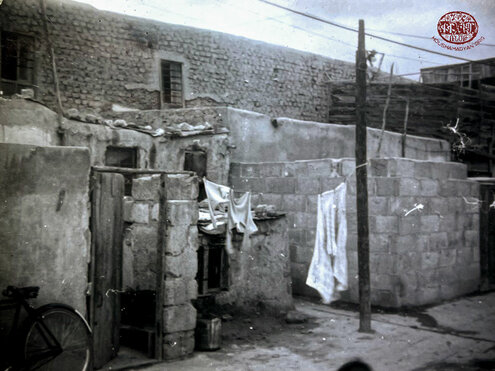

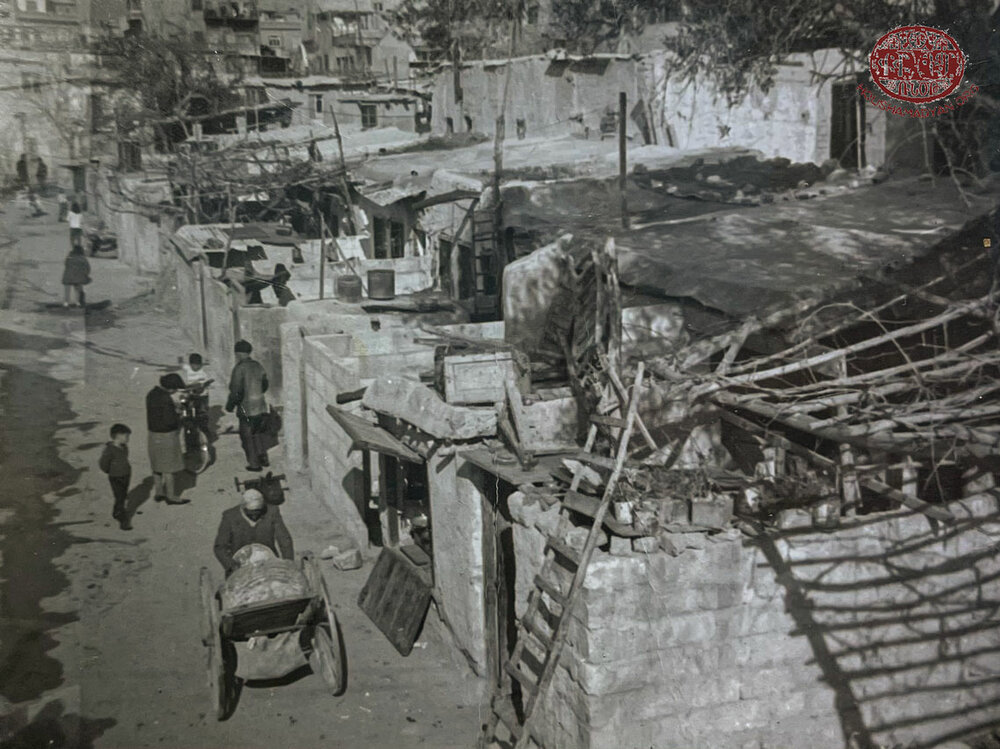

And thus, in the 1920s, the population of the Khcher's Camp, no longer needing their tents, moved into homes with triangular roofs. These homes were built of wood and thatched with a mixture of clay and mud. The triangular roofs were made of tin and were weighted down with bricks to prevent the wind from blowing them away.

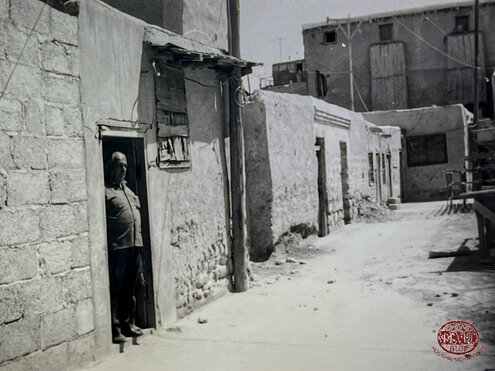

By the 1930s, the refugees’ economic situation had improved, and they began rebuilding their homes, using the architectural style of their homelands. Most of the new homes had two stories, and the roofs were flat – the architectural style of Ayntab and Marash. These homes lacked courtyards, and the two stories were connected with an external ladder. The entrance of the neighborhood led directly to the entrance of each of the homes.

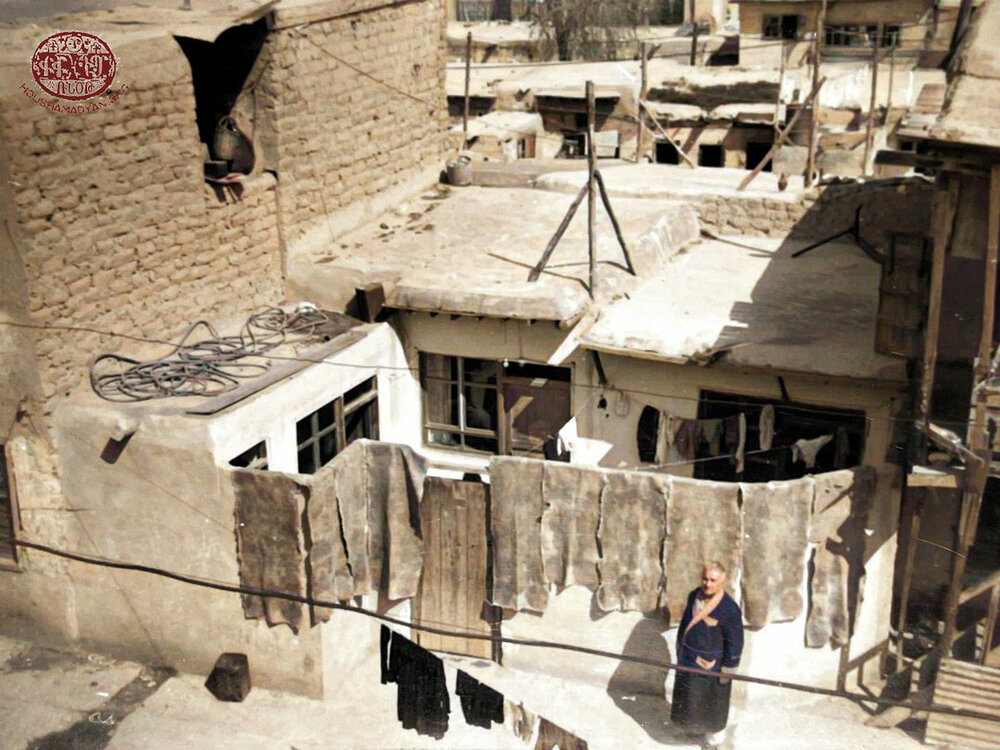

According to the testimony of Verjin Minasian-Der Bedrosian, an Armenian who lived in Damascus, the camp lacked the basic necessities of life. The ground was not flat, and there was no sewage system. Water and effluent often flowed down the middle of the road. In the summers, the roads were exceedingly dusty, and in the winters, they were exceedingly muddy. The homes had no outhouses of their own and used communal latrines. Water was obtained from various wells. Each well was equipped with a metal hand pump to allow the locals to pull up the water. The walls of the renovated homes were sometimes built of stone, and sometimes of clay and mud. Long logs reinforced the roofs and ceilings.

In the 1940s, when Armenian refugees reached new levels of prosperity, many of them demolished their old homes and replaced them with more modern residences. The stairs connecting the two floors were now internal; the walls were built of stone or concrete; and each of these new homes was provided with electricity and was connected to the city’s water and sewage systems. Eventually, the roads, too, were paved with concrete.

Most of the refugees who lived in the Khacheri Camp hailed from Marash, Ayntab, Adana, Mousa Ler (Musa Dagh), Ourfa, and Diyarbekir/Dikranagerd. Alongside these Armenians lived a few Assyrians, who were also natives of the same areas.

In his book The Armenians of Damascus [in Arabic], Sarkis Bourounsouzian describes community life in this refugee camp as simple and wholesome. The camp’s residents shared each other’s joys and sorrows collectively. Saturdays were dedicated to cleaning the camp. The roads were washed with water, laundry was hung up to dry, and preparations were made for Sunday. Saturday night was dedicated to feasts and celebrations. The neighborhood boasted its own musical band, with musicians playing the oud, mandolin, clarinet, and darbuka. They would play during these gatherings and sing popular songs.

Khcher was the neighborhood’s moukhtar (neighborhood leader/notary public), and one of the founders of the camp’s Papkenian School (founded in 1935).

As we have seen, especially in the early days of its existence, the camp’s population was impoverished, and the conditions were unsanitary. But the interior of the homes was clean and neat. On the floors, the walls, or the furniture, the women displayed the sheets and kilims (rugs) that they wove. The menfolk were mostly craftsmen – cobblers, tanners, makers of men’s ties, etc.

In 1947, a group of refugees living in this camp answered the call to resettle in Soviet Armenia and emigrated. They were replaced in the camp by Arab Christians who had hitherto lived in the suburbs of Damascus.

In the 1970s, renovations were launched, and most of the old two-story homes were converted into four-story buildings. The area entered a period of rapid growth. Armenian families continue to live in the area to this day.

Moukhtar Khcher, too, converted his home into a four-story building. The old well is still there, in the courtyard of this building. Khcher’s children and grandchildren still live in the building. In 1991, the neighborhood’s residents also included David Hovhannisian, the first ambassador of the independent Republic of Armenia in Damascus.

Refugees Living Inside the Damascus City Walls (Intra Muros)

These refugees lived inside the city, within the walls. They rented homes from local Arabs or rooms in local inns, mostly in the Bab Sharki, Bab Touma, and al-Abbara areas. In other words, these Armenians did not live in specifically designated refugee camps.

The Armenian Church Neighborhood (Bab Sharki)

The refugees in this area rented homes and rooms that belonged to the Armenian Saint Sarkis Monastery. Some of the refugees were provided with free shelter, namely the elderly, widows, and some extremely impoverished families. These homes surrounded the monastery on its northern, southern, and western sides. To this day, the southern portion of this area is called the “Armenian Church Neighborhood” (جادة كنيسة الأرمن). We must note that the Saint Sarkis Monastery was located in the east of Damascus, adjacent to the Bab Sharki gate. The church had stood at that site since the 15th century.

“Pelerin” Camp

Another group of refugees had settled down in the Bab Touma area of Damascus, near the Bab Touma Bridge, adjacent to the al-Takaf Mosque. The eastern borders of the camp immediately abutted the rear of the mosque. The refugees in this area consisted of about 35 families from Kharpert, who lived in rented homes with courtyards belonging to local Arabs. This neighborhood was known as the “Ousda [Master] Garabed Neighborhood.” Ousda Garabed was Garabed Melidosian, a native of Kharpert, and one of the founders of the refugee camp and its moukhtar. In later years, the area became known as the Pelerin Camp.

Abbara

A group of Armenian refugees settled down in the Abbara area of Damascus, in the huts and the inn built on the premises of the Armenian Saint Sarkis Church. Most of these refugees were helpless and elderly, and were provided shelter on property belonging to the church. These huts had once been used as shelters for Armenian pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem.

This refugee camp was very close to the Saint Boghos holy site, which was better known by the name of Abbara (عّبارة). This name has its own history. According to legend, when Saint Boghos (Saint Paul) was on the lam, he was hidden in a large jug at this site, and was thus able to escape his pursuers. The word abbara is Arabic for “portal.”

No traces of this camp have survived into the present.

Sources

- https://www.albayan.ae/books/from-arab-library/2017-11-21-1.3106878

- http://www.maaber.org/issue_april19/spotlights1.htm

- Sarkis Bourounsouzian, ارمن دمشق [The Armenians of Damascus], 2016, Damascus.

- Testimony: Verjin Der Bedrosian (nee Minasian). Recorded on October 15, 2021, in Damascus.