Movses Telfeyan Collection - Los Angeles

Author : Sofi H. Khachmanyan, 15.06.20 - translator: Simon Beugekian

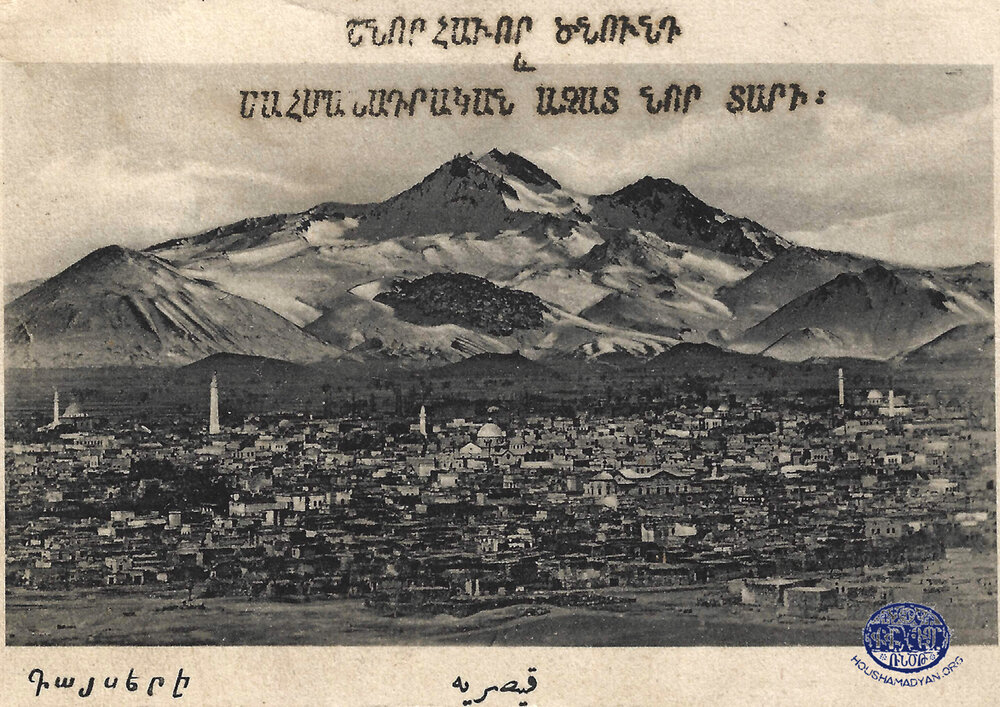

Commerce and the crafts were the primary occupational fields of the Armenians of Kayseri (Gesaria, Caesarea). Specifically, many of the city’s Armenians worked as importers/exporters, architects, carpenters, sculptors, jewelers, painters, tailors, weavers, silk farmers, butchers, etc. [1]

By the early 20th century, thanks to their talents as versatile businessmen, Kayseri Armenians had achieved a certain position in society and lived comfortable lives. They were the dominant force in the city’s markets.

In his wide-ranging work Badmoutyun Hay Gesario [History of Armenian Gesaria], Arshag Alboyadjian dedicates an entire section to the wealthy Armenians of the city, including the families of Kazaz Sarkis Telfeyan and his sons, Movses and Garabed Telfeyan. The book provides details of their lives both before and after the Armenian Genocide.

The Telfeyans and the Development of the Carpet Industry in Kayseri in the Late 19th Century

In the second half of the 19th century, Garabed and Movses Telfeyan were operating the silk-trading business they had inherited from their father, Kazaz Sarkis Telfeyan. They would import raw silk and silk fabric from Central Asia and Persia, then re-sell the merchandise both locally and to buyers in Constantinople and various European countries. Unfortunately, the silk trade soon experienced a crash throughout the region. Faced with this reality, the Telfeyan brothers, being astute businessmen, quickly pivoted to the carpet trade, then to carpet manufacturing, thus ensuring continued success for their business.

Carpet manufacturing in Kayseri, as an important branch of the city’s manufacturing industry, grew at a rapid pace in the mid-19th century. Within just 7-10 years, almost every Armenian family of the poorer or middle classes owned a carpet tazkah (dezgeah, loom) [2]. Aside from the Telfeyans, several other Kayseri enterprises were engaged in the carpet trade. The main reason for the growth of the industry in the city was the fact that carpets made from the finely worked wool and silk of Kayseri, dyed in the oriental style with natural dyes, had been received very well in Europe and were very popular there, leading to increased demand. These carpets were seen by Europeans as the equal of Persian carpets in quality [3].

It is important to note that the information provided by Alboyadjian in his book regarding the life of the Telfeyans is almost identical to the oral history preserved by the living descendants of the family. We will now provide detailed accounts of the lives and works of these captains of commerce.

Kazaz Sarkis Telfeyan

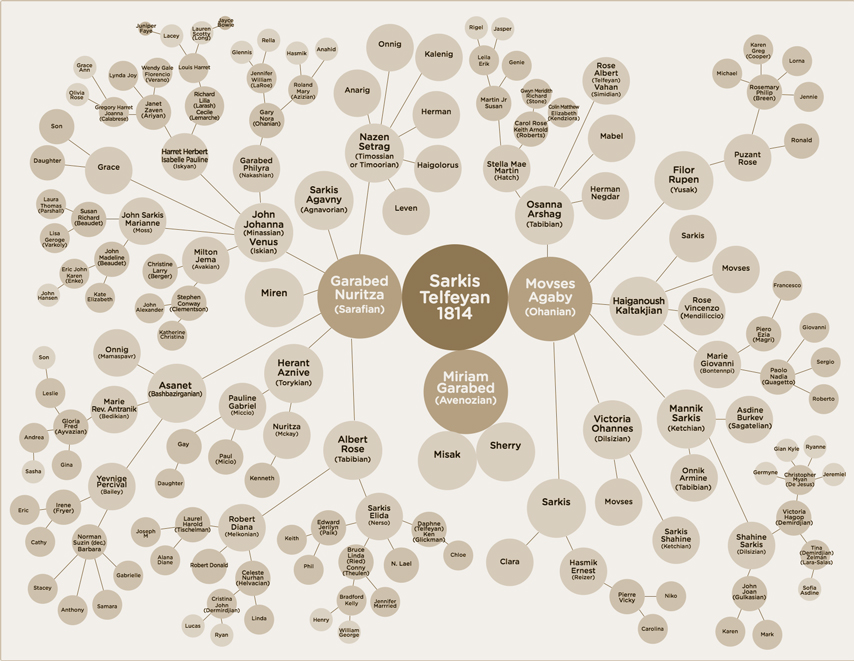

Precious little information about Kazaz Sarkis has been passed down to his descendants who now live in Los Angeles. He was born in 1814, and the date of his death is unknown, as is his wife’s name. According to Alboyadjian, in the early 19th century, he was one of the preeminent merchants in Kayseri, and one of the most recognizable members of the city’s business community. Kazaz Sarkis was engaged in the silk trade mostly with Bursa and Constantinople. He was one of the first Armenians of Kayseri who embraced Protestantism, and became one of the most well-known members of the city’s Evangelical community [4].

He was also well-known for his philanthropic work. One of Kazaz Sarkis’ dreams was to create an institution where local Armenian youth could receive higher education. This prompted him to become a member of the board of trustees of the Arkeos School of Kayseri [5]. As already mentioned, this great merchant had two sons, Garabed and Movses, who inherited their father’s business and expanded it. They would become the most celebrated Armenian merchants from Kayseri. Kazaz Sarkis also had a daughter named Mariam [6].

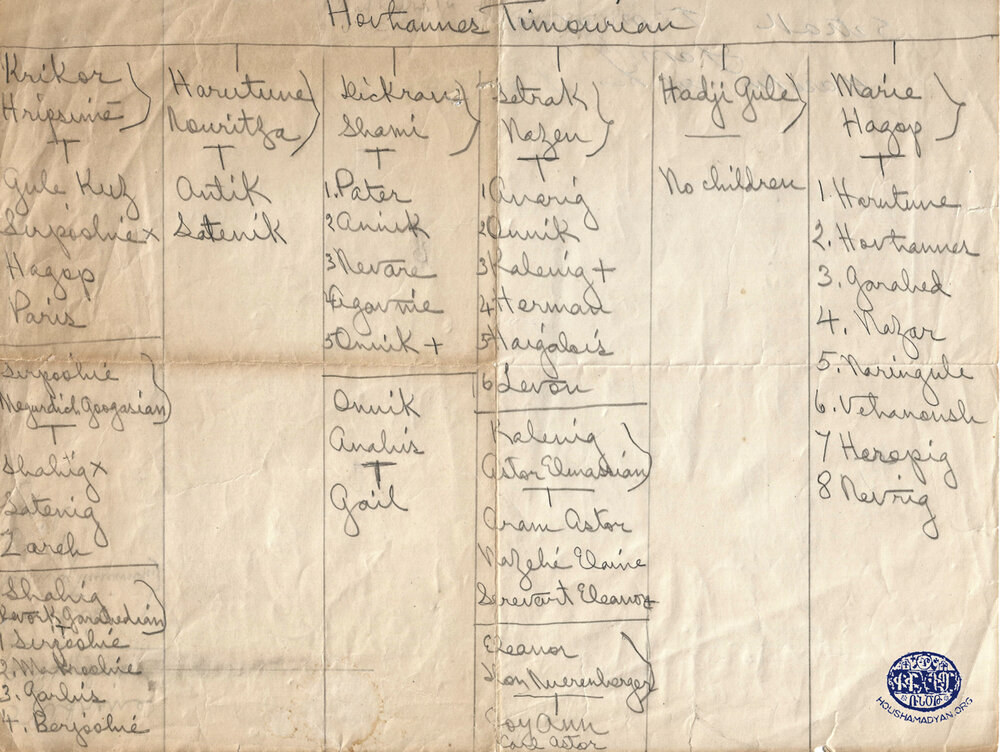

Garabed Telfeyan and Nouritsa Sarafian-Telfeyan

Sarkis Telfeyan’s oldest son, Garabed Telfeyan (1832-1906), received his early education in the local parochial school of Kayseri. In 1865, he married Nouritsa [7], the daughter of another prominent local family. Garabed was a bold businessman, and “as a result of his progressive spirit,” he left for Constantinople in 1886, 10 years before his brother, “unable to limit himself to the narrow confines of Kayseri” [8]. He later secured a good education for his children, and gradually relocated his business from Constantinople to New York. Later, he and his family moved permanently to America [9], where they lived comfortable lives [10]. He had five sons and three daughters [11]. His sons were Sarkis Telfeyan (1864-1914), Hovhannes Telfeyan (1868-1924), Miren Telfeyan, Hrand Telfeyan (1887-?), and Albert Telfeyan (1881-?). Alboyadjian provides only limited information about his daughters. We know that two of them were called Nazen and Asanet.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Garabed sponsored various Armenian projects in Kayseri and Constantinople [12]. Later, his children and their descendants continued the family’s philanthropic tradition in the United States.

Setrag Timourian and Nazen Telfeyan-Timourian

Here, we must introduce Setrag Timourian, the well-known carpet merchant from Kayseri. He was married to one of Garabed Telfeyan’s daughters, Nazen. The history of the Timourian family, as well as its rich collection of items, is of great importance, and will be discussed further in this article. Timourian was among the many businessmen in Kayseri who were initially engaged only in the trade of carpets, both local and imported from Persia [13]. Later, he expanded his business and began manufacturing carpets. In addition to being a successful and accomplished businessman, Timourian was a well-educated man. He evidently corresponded with many newspapers and magazines published in Kayseri. Timourian was also an expert in old carpets and rugs and had a very respectable personal collection. One of the rugs from his own collection is still kept in Los Angeles, in the house of his granddaughter Nazelie Elmassian.

1. Kayseri, 1888. Setrag Timourian (right, seated), his wife Nazen Timourian-Telfeyan (center, standing), and their two children. On the left, seated, is Hovhannes Agha Kelegian (Nazelie Elmassian Collection).

2. Setrag Timourian (center) with his two sons, in his office in New York, probably in 1913 (Nazelie Elmassian Collection).

Movses Telfeyan and Akabi Ohanian-Telfeyan

Kazaz Sarkis’ youngest son, Movses Telfeyan (1844-1900), received his early education in the Hagopian School, adjacent to the Saint Sarkis Church in Kayseri. He also received private lessons in Greek. He grew up to be a successful businessman and a well-known philanthropist. Movses and his wife created a large family (five daughters and one son) [14].

Movses was the first businessman in Kayseri to manufacture high-quality djedjims (cecim or cicim in Turkish), which would later revolutionize the carpet industry. A djedjim was a simple weave of fabric, usually of cotton or silk, that looked very much like a rug, and had stripes of different colors. Djedjims were usually used as blankets, tablecloths, or curtains. Many valuable djedjims were embroidered with symbols and charms, including the djedjim used by the Telfeyans. At the height of his success, Movses Telfeyan had more than 200 Armenian, Greek, and Turkish workers in his factory. In order to sell his products locally and to export it, M. Telfeyan also had many Armenian, Turkish, and European business partners. During his lifetime, Movses Telfeyan sponsored and supported many Armenian educational and religious initiatives.

After his death, his wife, Akabi, continued his philanthropic activities. According to the oral history preserved by the family, Akabi was one of the principal managers of M. Telfeyan’s factory. She was one of the few women in Kayseri who actively helped their husbands run their businesses. Akabi also worked on designing and improving the factory’s products. This, of course, was a rare phenomenon in Kayseri. The younger members of the family always spoke with great respect and reverence about Akabi. Tina Demirdjian was told by her grandmother that Akabi was a proficient carpet and djedjim weaver, and when necessary, was ready to teach the firm’s employees the finer points of this art. According to the family’s oral history, Akabi was the reason the whole family embraced the Evangelical faith.

After the 1895-1896 massacres in Kayseri, Movses Telfeyan and his family were forced to relocate to Constantinople. There, he tried to re-establish his business. He even founded a branch in Bulgaria [15]. Unfortunately, he did not succeed. He lost hope, became ill, and died in 1900. His children, most of whom were married, relocated to various western countries. Two of them moved to New York or to other east-coast American cities, and some of their descendants later moved to Los Angeles, California [16].

1. Mannig Telfeyan (left) and Victoria Telfeyan (later Dilsizian, right), 1898, Constantinople (Tina Demirdjian Collection).

2. Akabi (foreground, on the right) holding Sarkis’ (Victoria’s son) hand and Mannig with her daughter (background). Constantinople, photographed by Sebah (Pera, Constantinople) (Tina Demirdjian Collection).

3. Victoria Telfeyan-Dilsizian, Constantinople, 1905 or 1906. Photographed by Sebah (Pera, Constantinople) (Tina Demirdjian Collection).

The Telfeyans and the 1895 Massacres in Kayseri

While Garabed and his family left their native city long before 1895, Movses continued to live and work there. When the Hamidian massacres broke out in that year, Movses was away from the city on business. On that terrible morning, most of his children, and two of his grandchildren, were asleep at home. From the kitchen window, Akabi saw a mob of Turks setting fire to Armenian homes, after which they began approaching their home [17]. Bravely, she organized the defense of the household. She ordered the children to immediately take cover in the cellar, then distributed weapons to the five servants. Armed with a gun herself, she instructed the men to shoot out of all the windows, in order to give the impression that a large force was defending the house. She ordered them to aim at the ground and not to kill anyone, but also to not allow the attacking mob to break into the house on any account.

But the Turkish mob had already set the neighboring house on fire, with women and children still inside. The fire gradually approached their home. Akabi would probably not have been able to withstand the assault by herself, had it not been for the sudden appearance of a high-ranking Turkish military officer. This officer, being acquainted with the Telfeyans, immediately ordered the Turks to leave the family alone, reminding them that Movses Telfeyan had always created jobs for the local Turks. The officer’s appearance saved the family from certain death.

The main source of this chapter in the family’s history was the family’s youngest daughter, Mannig, who handed the story down to Tina Demirdjian.

According to the family’s oral history, when Movses and his son Sarkis returned from their travels, discovered what had happened, and saw the prevailing situation in the city, Movses understood that they had to permanently and immediately leave Kayseri. The exact words he uttered on this occasion have been preserved for posterity: “We will never again be able to rest our heads on our pillows here.”

In 1896, Movses and his family left their native city and moved to Constantinople, believing that in the cosmopolitan capital, it would be possible to live safely. As we have already mentioned, two years later, he fell ill and died, having lost most of his wealth and his hope. Two of his daughters, Filor and Ovsanna, had already been married when the family left Kayseri. Ovsanna and her husband later moved to the United States. Another one of his daughters, Hayganoush, had married and moved to Italy by 1896. Sarkis’ son, who was also married, later lost his property, left for Italy, and eventually settled down in France.

1. Mannig’s family, Constantinople. Mannig Telfeyan-Kechian (left) and her husband, Sarkis Kechian. In the center, left to right: Asdene, John, and Shahine. Photographed by Sebag (Pera, Constantinople) (Tina Demirdjian Collection).

2. Nazen Telfeyan-Timourian (right) with her sister Asanet (Nazelie Elmassian Collection).

The Telfeyan Family in the United States

After Movses Telfeyan’s death, his son, Sarkis, inherited his business in Constantinople. He had great success not only in the carpet trade, but also as a landowner. Immediately before the entry of the Kemalist forces into the city, in 1922, he fled to Italy, and from there, to Paris. The Turkish authorities confiscated all of his wealth as “abandoned property.”

Some of Movses Telfeyan’s family members were not able to leave Constantinople until the late 1930s or even as late as 1945, when they were able to obtain travel documents with bribes. Garabed’s family, which already lived in the United States, settled down mostly in New York, where the sons founded their own businesses selling carpets. Garabed’s daughter Nazen and her husband Setrag Timourian moved from New York to the city of Fresno in California, and from there to Los Angeles, where they settled down. The house that their daughter Kalenig Timourian-Elmassian bought in the 1930s is still the residence of her daughter, Nazelie Elmassian. Her grandfather, Setrag Timourian, also lived in that house in the last days of his life, and died there.

The Collections of Movses and Garabed Telfeyan and the Armenian Dress and Textiles Project

The families of Garabed and Movses Telfeyan, who left the Ottoman Empire at different times, took with them many household and personal items that were used by them or by late members of their families. It is the women of the two families who, until the present day, have preserved these items, even after having moved from city to city or state to state in the United States. There are now two separate collections, both kept in Los Angeles, each respectively belonging to Movses Telfeyan’s and Garabed Telfeyan’s branches of the family.

The history of Moves Telfeyan’s family attracted the attention of a group of American scholars in the late 1990s, when Movses’ great-granddaughter Vicky and her daughter Tina, in the city of Whitestown in the state of New York, examined their mother’s and grandmother’s belongings, and found their bokhchas, which had been stored away for many long years. In these bundles, Shahine had preserved valuable items that had belonged to her mother Mannig and her aunt Victoria in Kayseri and Constantinople, as well as other family members and relations.

Mannig was the youngest daughter of Movses Telfeyan, and Shahine was Mannig’s youngest daughter. Vicky is Shahine’s daughter, and Tina is Vicky’s daughter. These women were responsible for the preservation of the Telfeyan collection, and its survival down to our days. Victoria was Movses and Akabi’s daughter. She had one son, named Sarkis.

Among the objects in the collection are valuable rugs [18], one of which was a wedding present from Akabi to her daughter Victoria (measuring 2 meters x 1.22 meters). The other rug was gifted by Victoria to her son Sarkis on an undetermined occasion. The collection also includes one small square rug with silk tassels, which belonged to Mannig. It was used as a piano cover. According to the oral history preserved by the family, all three of these rugs were manufactured in Movses Telfeyan’s factory prior to 1896, the year the family left Kayseri. There are also two beautiful embroidered djedjims in the collection. They belonged to Tina’s paternal grandfather. According to Tina’s father, these djedjims, too, were manufactured in Movses Telfeyan’s factory.

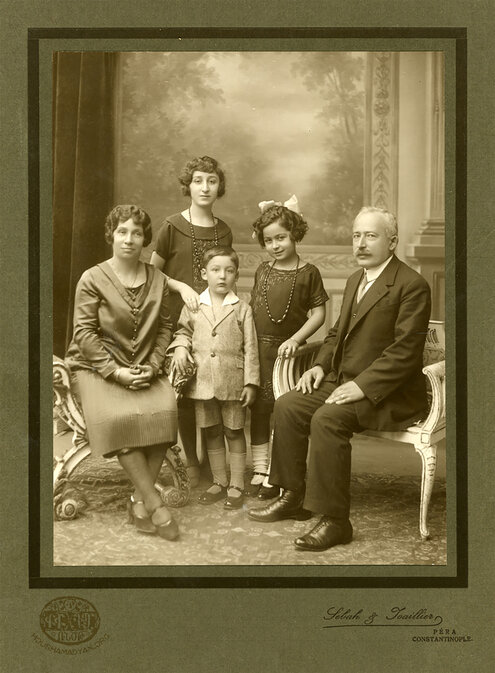

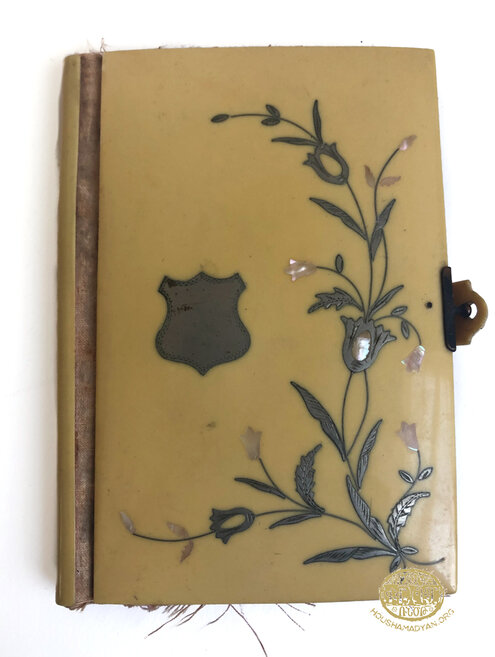

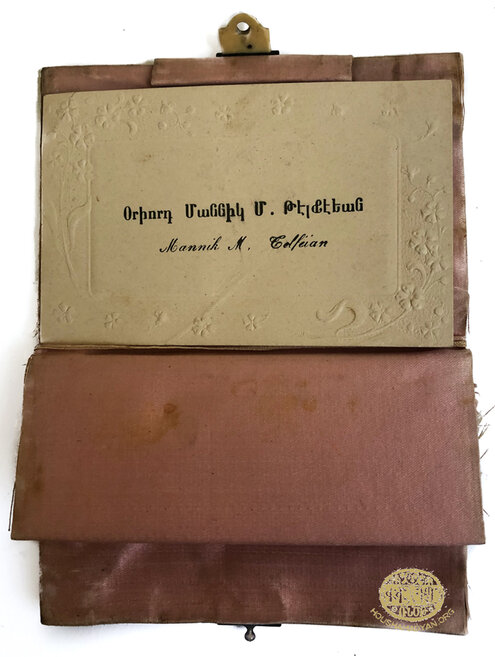

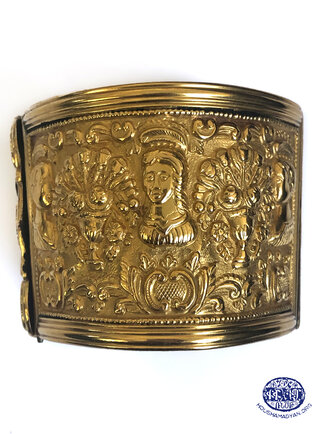

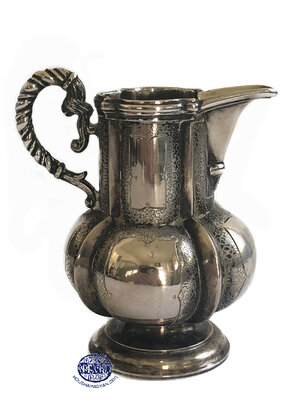

The Armenian Dress and Textile Project was founded in Los Angeles, in 1999, with the goal of studying the Telfeyan family’s rich collection. The collection, aside from rugs and carpets, includes various valuable items that belonged to the family’s members, including clothing, shoes, valuable ornaments, sheets, boxes, elegant toiletry items, other valuable personal items, items with ceremonial significance, photographs, writings, etc. Most of these belonged to Movses’ two younger daughters, Victoria and Mannig. As we have mentioned, the collection was preserved by Mannig’s daughter Shahine. The collection was then inherited by Shahine’s daughter, Vicky Demirdjian, and granddaughter, Tina Demirdjian. Since Vicky’s death, almost the entire collection has been kept in Tina’s home in the city of Glendale, California.

The second Telfeyan collection, belonging to the Nazen Telfeyan-Timourian (daughter of Garabed Telfeyan) branch of the family, was discovered thanks to the Armenian Dress and Textile Project. The project organized an exhibition of the first Telfeyan collection at the Doctor’s House Museum and Gazebo, in the courtyard of Glendale’s Brand Library. A visitor to the exhibition, Nazelie Elmassian, informed the organizers that she, too, was a descendant of the Telfeyan family on her mother’s side, and that she had many similar items in her care. Nazelie was the 95-year-old granddaughter of Nazen, Garabed Telfeyan’s daughter, and her husband Setrag Timourian. Nazelie inherited her collection from her mother, Kalenig Timourian-Elmassian, Nazen’s daughter [19]. Nazelie Elmassian’s collection is also rich with various items, photographs, and writings that belonged to her branch of the family. Recently, with the help of the Armenian Dress and Textile Project, Nazelie donated the bulk of her collection to the Ararat Museum, located in Mission Hills, California, where it is currently on display.

The Stewards of the Telfeyan Family Collection

Garabed Telfeyan’s great-granddaughter, Nazelie, faithfully preserved the collection she inherited from her mother in her home. The collection includes various objects kept in wooden, carved, and numbered cases also brought from Kayseri.

Nazelie does not know much about the Telfeyans. Her mother, Kalenig, despite being a very educated woman, preferred not to share the story of her past with her family. She encouraged her daughter to quickly conform to American society. In fact, Nazelie served as a member of the Medical Corps in the United States Navy. Nazelie remembers her grandfather, Setrag Timourian, very well, and is always happy to talk about him. To this day, Setrag Timourian’s room, with its furniture, as well as Nazelie’s parents’ and brother’s rooms, are preserved just as they were left. Nazelie never married, and continues to live alone in the house. After her service in the Navy, and after attending university, Nazelie worked as a teacher. When asked why she has gone to such lengths to carefully preserve the collection that belonged to her loved ones, she explains that those are her family’s priceless memories, which warm her heart and inspire her with great pride. Today, Nazelie, who is on the threshold of her centennial, is very happy to see the great interest in her family’s mementos, which have found a safe home in the Ararat Museum.

As we have already mentioned, the Movses and Akabi Telfeyan collection was preserved by their two younger daughters, Victoria and Mannig. Victoria died at the tender age of 26, leaving behind one son, Sarkis. Mannig, who had grown up with Victoria and was very attached to her, decided to keep all of Victoria’s personal items as mementos, including all the unused items in her dowry. Alongside her two sisters, Mannig cared for Victoria’s orphaned son, Sarkis. In order to prevent the family’s wealth from being split, Mannig had her younger daughter, Shahine, marry Sarkis [20]. Shahine’s daughter Vicky stated that Mannig had written a letter to Shahine, in Turkish but using Armenian letters, instructing her to take the greatest care of the items in the family’s collection, as they were the embodiment of the family’s long history. According to Tina, over the years, other adult women in the family also entrusted Shahine with various items of significance for safekeeping. For this reason, the collection grew to be quite large. The items presented here are only part of the collection. Shahine preserved the items entrusted to her for almost 50 years.

Vicky, Shahine’s daughter, speaks Armenian, and is also one of the keepers of the family’s collection. In her home, she still keeps many rugs that were brought from Kayseri. In years past, she has told the story of her family many times, passing on her memories to her daughter Tina.

The current steward of the Movses Telfeyan Collection is Tina. As the heir of Movses Telfeyan’s legacy and the custodian of the family’s memories, she preserves the collection with great care. She is also the keeper of the family’s oral history. She remembers her great-grandmother Mannig and grandmother Shahine very well. Mannig died when Tina was 11 years old. During her childhood years, when visiting with family in the summertime, Shahine would open the old bokhchas and would tell the children about the clothes, embroidery, and other items that told the family’s story. Tina’s memory retained the stories told by Mannig, Shahine, and Vicky with astounding clarity, and she often alludes to her family’s history in her own creative work. As a poet, Tina has attempted to make her work a vessel for the family’s history, relaying it to the wider Armenian and American communities.

The members of the Telfeyan family were saved from the Armenian Genocide thanks to their decision to leave their native city when they became convinced that they could no longer “rest their heads on their pillows” there. Fortunately, the women of two branches of the family were able to save from destruction the mementos of their family’s past, each of which is a relic of Kayseri’s Armenian culture. These items are also the living witnesses of the history of the Telfeyan family in their native Kayseri.

- [1] Arshag Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario [History of Armenian Gesaria], Volume B, H. Papazian Press, Cairo, 1937, pp. 1479-1471, 1492-1494.

- [2] The people of Kayseri had great appreciation for carpets and rugs, and accordingly decorated their houses with them (Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, pp. 1499-1500).

- [3] The Bursa silk brought to Kayseri via Constantinople was supplemented by the locally produced silk and wool, spun and dyed by locals before being resold (Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, page 1503).

- [4] Many of Kayseri’s wealthy citizens had cultivated close friendships with American missionaries. Some converted to Protestantism/Evangelicalism in order to remain relatively safe from the persecution and transgressions of the Turks (family history).

- [5] Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, page 2200.

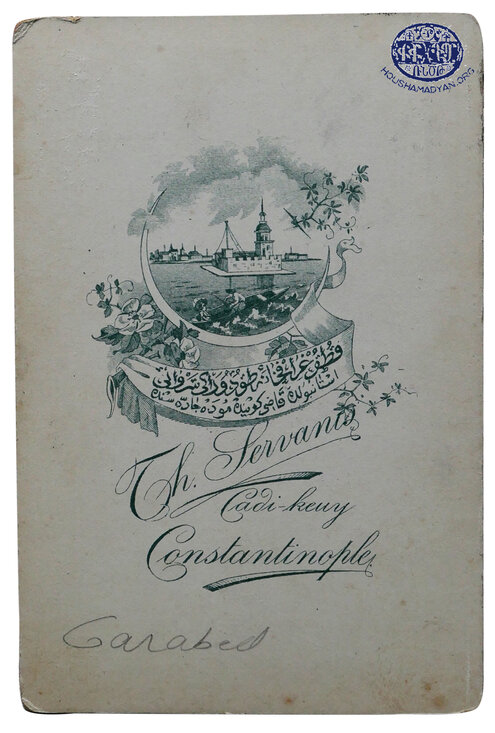

- [6] Alboyadjian mostly provides the names of the male children. The female members of the family are largely omitted from his work. This information is based on a family tree created by one of Garabed Telfeyan’s grandchildren.

- [7] Nouritsa died in 1904. Her year of birth is unknown.

- [8] Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, page 2200.

- [9] Ibid., pp. 2200-2203.

- [10] Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, page 2200; also the family’s oral history.

- [11] This is according to Alboyadjian, but the family’s own oral history maintains that Garabed had only two daughters, Nazen and Asanet.

- [12] Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, pp. 2200-2203.

- [13] In his memoirs, Setrag Timourian provides extensive details on the growth of the carpet trade in the mid-19th century in Kayseri. His journal is included in the Nazelie Elmassian collection, and is currently being prepared for publication by the Ararat Museum. In addition to Setrag Timourian, there were other carpet merchants in Kayseri, including the Topalians (Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, page 2203).

- [14] Alboyadian mentions that they had two sons, but the family’s oral history only remembers Sarkis. M. Telfeyan’s family photograph also only shows Sarkis, who was named after his grandfather, Kazaz Sarkis. Several boys born to different branches of the family were named Sarkis.

- [15] The Bulgarian branch was managed by Mesrob’s son Sarkis (Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, page 2200).

- [16] Ibid.

- [17] The homes in Kayseri were built adjacent to each other, for the sake of improving security. This way, the residents could organize a defense of their homes from the inside if necessary, or quickly organize an evacuation (Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, page 1673). As a consequence, whatever happened in one home was a matter of immediate concern for the neighbors.

- [18] The people of Kayseri had a custom of gifting valuable carpets and rugs to their children on important occasions. A wool rug was worth about 2-5 Ottoman pounds, while silk rugs were worth 15-20 pounds (Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, page 1504).

- [19] The women of this branch of the family include Nazen Telfeyan-Timourian, Kalenig Timourian-Elmasian, and Nazelie Elmasian.

- [20] The Armenian Apostolic Church would not marry them due to their kinship, so Sarkis and Shahine married in an Italian Catholic church.