The Collections of Garabed Telfeyan’s and Setrag Timourian’s Families | Los Angeles

Author : Sofi H. Khachmanyan, 04.12.20 - Translator: Simon Beugekian

Garabed Telfeyan was the oldest son of Kazaz Sarkis Telfeyan, the renowned silk merchant from Gesaria (Kayseri). Sarkis was also one of the leading importers of wholesale coffee into the area. Most probably, the family acquired the surname Telfeyan for this very reason [1]. According to the family history, Sarkis was also involved in the trade of glue and gold and owned a small carpet factory.

For many years, Garabed Telfeyan’s great-grandson’s daughter, Jennifer Telfeyan-LeRoy, has been collecting manuscripts, documents, and photographs relating to her family’s history from her relatives. Jennifer also provided us with a family tree that she prepared, as well as some of the information included in this article. Jennifer currently lives in New York.

In the second half of the 19th century, Sarkis’ two sons, Garabed and his younger brother Movses, were at the helm of the silk-trading business that they had inherited from their father. They would import raw silk and silk cloth from Central Asia and Persia, which they would then resell locally or export to Constantinople or various European countries. But at the end of the 19th century, after the collapse of the silk trade, the Telfeyan brothers quickly transitioned to the manufacturing and trade of carpets, like many of their peers. Garabed became one of the best-known and most successful merchants from Kayseri, while Movses Telfeyan made his name as a manufacturer and trader of djedjims and rugs [2].

Throughout their careers, the brothers sometimes collaborated with each other, and sometimes with other merchants. We know from the memoirs of Setrag Timourian [3], the well-known Kayseri merchant and husband of Garabed’s oldest daughter, that the Telfeyans expanded their market presence by sending the products they manufactured to Constantinople. There, the merchandise was sold in a store owned by their business partner, Hovhannes Kelegian. This arrangement allowed all involved to reap great profits. Hovhannes Kelegian was the brother-in-law of Garabed’s wife, Nouritsa. He owned a small and not-very-profitable cash and gold exchange business in the capital, and was thus glad to enter into a lucrative partnership with the Telfeyans [4].

The Garabed Telfeyan and Nouritsa Sarafian-Telfeyan Branch

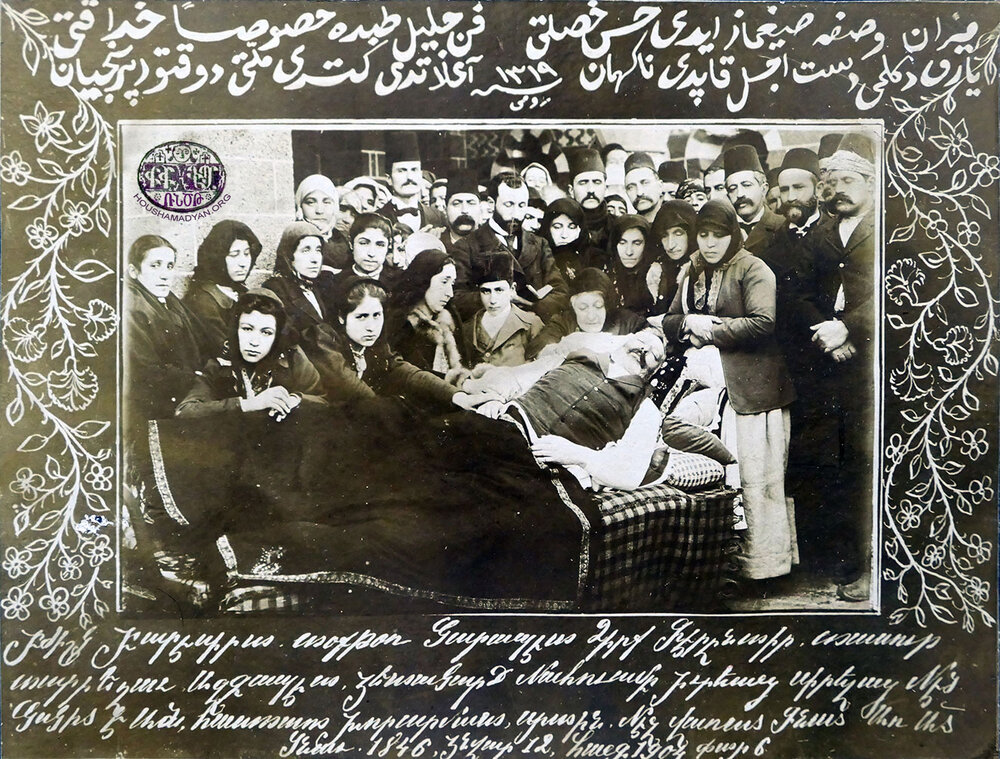

In 1865, Garabed Telfeyan (1832-1906) married Miss Nouritsa (date of birth unknown, died in 1904). She was the daughter of a prominent family in Kayseri.

By the end of the 19th century, Garabed had begun expanding his business. Constantinople remained its hub, but he also opened offices and employed agents in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East [5].

His aim was to eventually open a branch in America. According to Setrag Timourian’s memoirs, Garabed pursued this goal by first sending his oldest son, Sarkis, 17-18 years old at the time, to New York. Sarkis was accompanied by one Hrand Giregchian from Roberts College (Constantinople). Garabed also sent a quantity of carpets along with his son, with which the latter was to open the first Telfeyan store in America [6].

Despite his youth, in 1888, Sarkis founded the firm S. Telfeyan and Associates in New York. Within a short period of time, he had achieved significant success. Only then did Garabed make the move to America with the rest of his large family [7]. There, he and his sons began expanding their business [8].

According to information provided by Arshag Alboyadjian, Garabed had five sons and three daughters, but the family tree only shows five sons and two daughters [9]. The surviving family photographs and the memoirs of Setrag Timourian feature four sons and two daughters [10]. Timourian’s memoirs also state that when Garabed Telfeyan invited his brother Movses to join him in Constantinople as a business partner, Movses traveled to the capital with Garabed’s family, which included Mrs. Nouritsa and Garabed’s sons Hovhannes, Asanet, Hrand, and Albert. The family’s oldest daughter, Nazen, was already married by this time. Sarkis was already in Constantinople, and there is no mention of Mihran. All the other children later moved to the United States, and they appear in the family photographs.

The birth and death dates of some of the family members are included in Arshag Alboyadjian’s book, Badmoutyun Gesario [History of Gesaria/Kayseri] [11]. Unfortunately, Alboyadjian mostly focused on the family’s men, and provided little information on its female members. Most of the information on the women is mentioned only in connection with their fathers, brothers, or husbands.

Garabed’s children were Nazen Telfeyan-Timourian (1862-1922), Sarkis Telfeyan (1866-1914), Hovhannes (John) Telfeyan (1868-1924), Mihran Telfeyan (1870-1873), Asanet Telfeyan-Bashbazirkanian (later Pashian) (1873-1920), Hrand Telfeyan (1878-1937), and Albert Telfeyan (1881-1959).

Garabed’s family tree is extensive. But from the information we have, it is clear that two of his sons, Sarkis and Mihran, did not father any children. In an interview [12], Roland Telfeyan stated that Sarkis did not have any children with his wife, Aghavni Aznavorian-Telfeyan, and that he died at the age of 48; while Mihran, as we have already mentioned, died at a young age in Kayseri.

Sarkis Telfeyan

Garabed’s oldest son, Sarkis Telfeyan, had a talent for business. He replaced his father as the head of the family firm. Under his leadership, the Telfeyans were able to accumulate a significant amount of wealth thanks to their successes as carpet merchants [13]. Following the example of his parents, Sarkis also dedicated a significant portion of his income to philanthropy. In 1916, in New York, he founded the Telfeyan Evangelical Fund, which remains in existence today. Sarkis’s donations to the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions were earmarked to support the education of Armenian youth in the Ottoman Empire, specifically those studying in the schools and orphanages administered by this American Protestant organization [14].

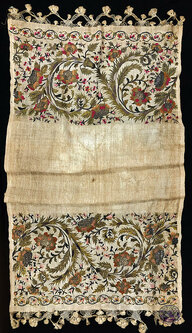

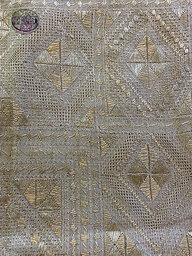

Tablecloths in various styles of embroidery

Hovhannes (John) Telfeyan

After Sarkis’s death, in 1914, Garabed’s second son, Hovhannes (John), alongside his brothers, changed the name of the family business to “S. Telfeyan and Brothers.” He assumed leadership of the firm, and under his management, it grew and became one of the three largest and most important importers of eastern carpets into America [15]. As the business expanded, Hovhanness began purchasing wool from the English city of Manchester. Most of the wool was transported to the Iranian city of Kashan, where the Telfeyans owned carpet factories. From there, the carpets were exported to various corners of the world [16]. Under Hovhannes’s leadership, the Telfeyans developed commercial relationships with China, Eastern Asia, Europe, and many other countries [17].

In 1917, Hovhannes Telfeyan founded the Armenian Evangelical church located on 34th Street in New York City, as well as the Armenian Missionary Association of America (AMAA), over which he presided. He also made many respectable contributions to the Telfeyan Evangelical Fund, which was founded by his brother [18].

Hrand Telfeyan

Garabed’s third son, Hrand Telfeyan, was also an educated man and was also engaged in the carpet trade. Hrand served as the treasurer of the Armenian Evangelical Association. He made sizeable contributions to support the construction and furbishing of the New York Armenian Evangelical church. He contributed to the Telfeyan Evangelical Fund and sponsored various educational and athletic initiatives [19].

The large, numbered chest in which the members of the Armenian Dress and Textiles Project first found the majority of the clothing and handmade items presented here. The chest bears the date 1883. It has a length of 114 centimeters, a width of 56 centimeters, and a depth of 64 centimeters.

Albert Telfeyan

Garabed’s youngest son, Albert Telfeyan, was one of the founding and influential members of the New York Armenian Evangelical church. He supported the Telfeyan Evangelical Fund and many other philanthropic initiatives. Albert was also engaged in the carpet trade and was an intrepid businessman. From our conversations with Jennifer, we know that Albert’s role in the family business mostly concerned the procurement of raw materials and the logistics of the distribution of merchandise. A. Alboyadjian describes one daring project that Albert undertook in 1917. During World War I, when it became impossible to import products into America after German submarines began sinking American trans-Atlantic liners, Albert traveled to Russia, and then proceeded to Persia. He stayed in Persia for a year, bought a large quantity of carpets, and shipped them to America on sailing ships. Then, proceeding via India, he circumnavigated the globe and crossed the Pacific Ocean to reach San Francisco [20]. Albert Telfeyan remained close with his sisters and their families throughout his life.

***

After the death of the two oldest brothers, Sarkis and Hovhannes, the family business was led by the younger brothers, Hrand and Albert, between 1926 and 1932. They had the help of Hovhannes’s sons, Garabed and Harret (Herbert). After 1932, the family’s company was divided into three separate firms, one going to Hrand, the second to Albert, and the third to Garabed and Harret. Hrand’s company survived for only a few years, while Albert’s survived into the 1950s. The third company, aside from Garabed and Harret, also employed Hovhannes’s two younger sons, Milton and John. These four men ran the company for some time, partnering with Othen, an American firm, and mostly selling artificial carpeting.

The Setrag Timourian and Nazen Telfeyan-Timourian Branch

Setrag Timourian (1860-1946), the famous Kayseri carpet merchant, was the husband of Garabed Telfeyan’s oldest daughter, Nazen (1862-1922). The lives of the Timourian and Telfeyan families were closely intertwined, and for this reason, we consider it important to study the history of this family and the rich collection it has passed down to us. The collection’s current keeper is S. Timourian’s granddaughter, Nazeli Elmassian (the daughter of Kalenig, Nazen’s only daughter).

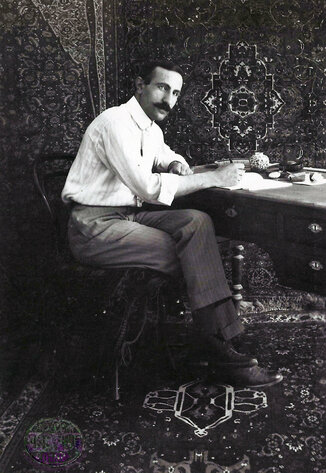

S. Timourian spent the last days of his life in Kalenig’s home, and died there. While living there, he wrote his memoirs. Timourian was not only a successful merchant, but also an erudite man.

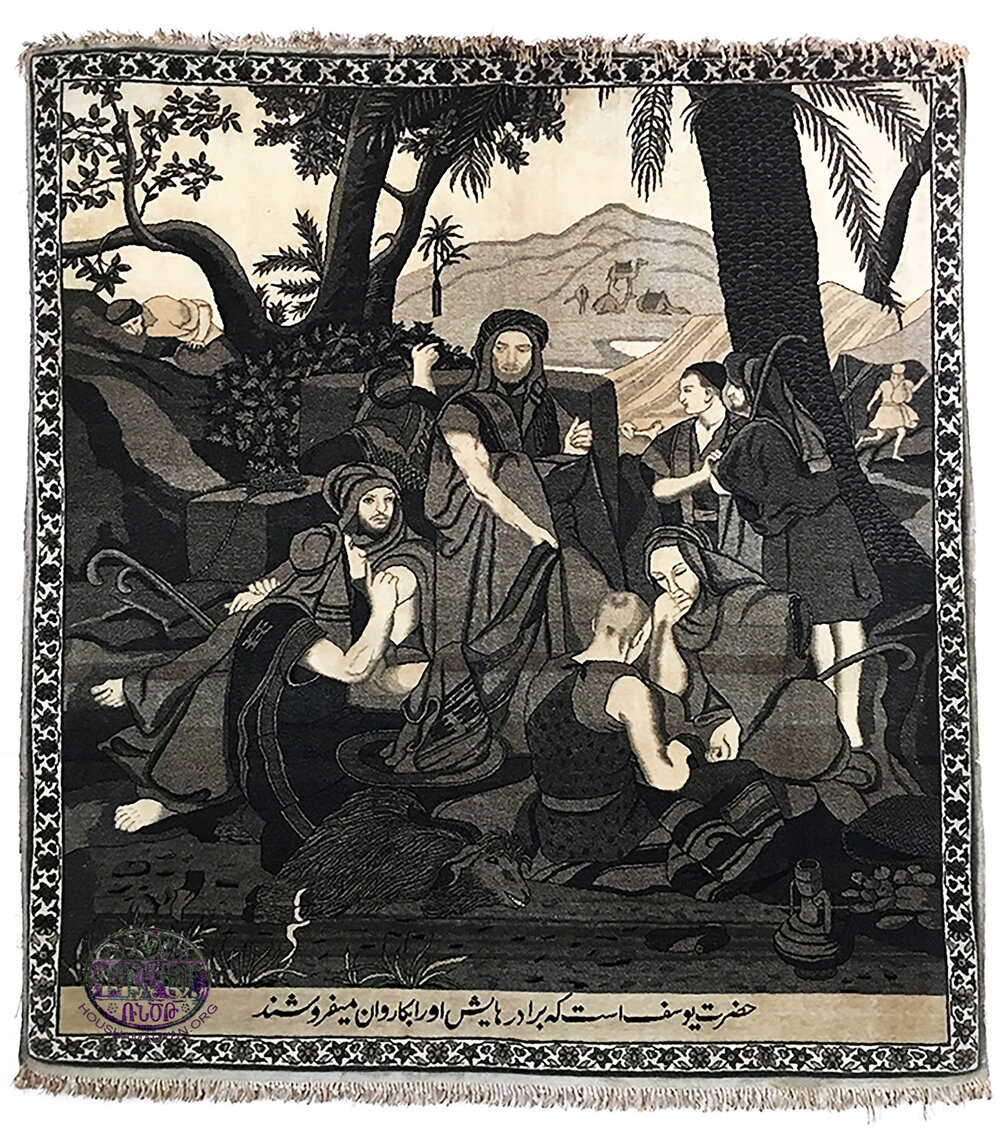

S. Timourian was an expert in carpets and owned a respectable collection of his own. During his years in Kayseri, he was involved in the trade of antique carpets, which he mostly obtained from Persia, Kayseri, and the surrounding region. He then resold these antiques locally, as well as to clients in Constantinople, Europe, and Cairo. In his memoirs, Timourian provides a list of other notable, contemporary merchants in Constantinople and Kayseri: Kavdjian, Koundakdjian, Ohanian, Kelegian, and Telfeyan. He also mentions the Telfeyan/Timourian companies.

In his memoirs, Setrag Timourian explained what compelled him to enter the carpet trade. First, we must mention that even before Setrag’s marriage to Nazen Telfeyan, the Telfeyan and Timourian families had enjoyed a good relationship. Setrag had been a young orphan, and after overcoming myriad obstacles, had opened a small store in Kayseri to sell silk. Meanwhile, the brothers Garabed and Movses Telfeyan had learned how to make djedjims from their uncle Gavisian. Movses Telfeyan sent the djedjims, carpets, and rugs produced in the Telfeyan factory to Constantinople, to be sold in the store owned by Hovhannes agha Kelegian, his wife’s brother-in-law. When he realized how profitable the Telfeyans’ business was, the young Timourian decided to abandon the silk trade and instead deal in carpets. He was very satisfied with this change, as the trade in antique carpets and rugs allowed him to earn exponentially more than he did before.

Timourian made several notable deals in the wholesale and resale markets. For example, as a result of his business dealings in Sivas/Sepasdia and the surrounding area, he was able to obtain many antique carpets and rugs, specifically from Gortz and Kula, and even from Isfahan. Later, he would also obtain Mosul rugs and other products from Iran. Back in Kayseri, in the first year or two after closing his silk store, he engaged in the production of carpets and djedjims, even competing with the Telfeyan brothers for some time. In the early years of his career, for a period of three or four years, Setrag also went into business with his father-in-law, or worked for him.

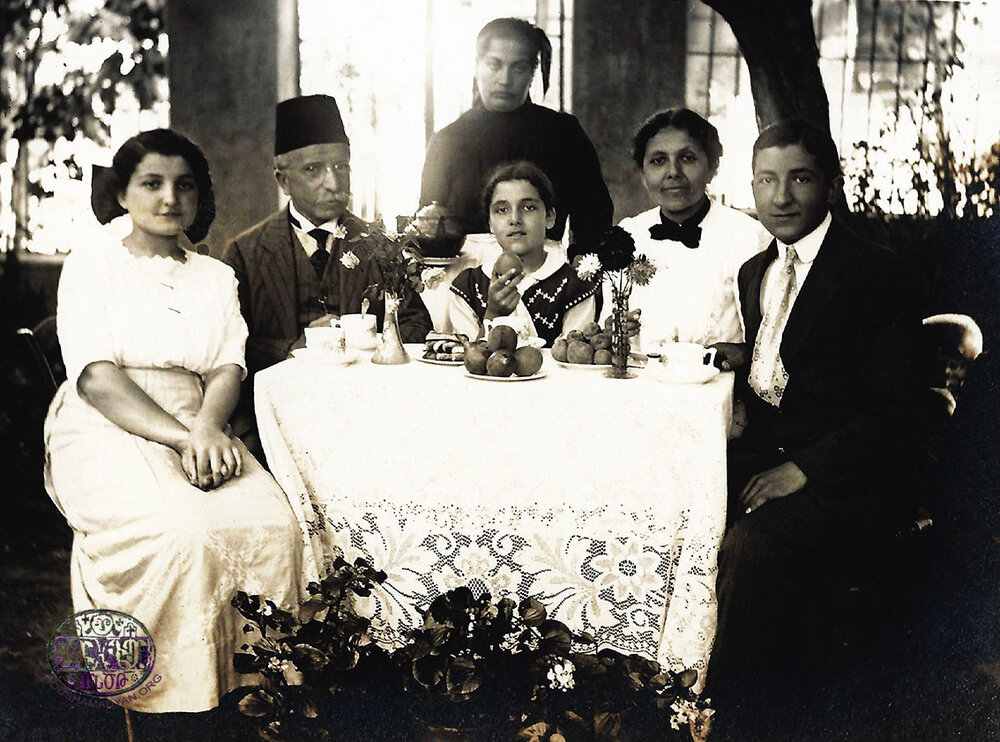

Setrag Timourian and Nazen were married on June 23, 1883, in the newly built Saint Krikor Lousavorich Church of Kayseri. Setrag loved his wife deeply, and the two shared a powerful bond throughout their lives. They had five sons: Onnig, Anarig, Haygalous, Levon, and Herman; and one daughter, Kalenig (1890-1960). Setrag and Nazen also had three other children who died at a young age: Hripsime died in Kayseri, and Herman (the first son of this name) and Srpouhi died respectively on the journey to Constantinople and the journey back.

In November 1895, the Hamidian massacres reached Kayseri. Like other families, the Timourians lost everything that they had built or earned over the previous 30 years. They decided to leave their native city and move to Constantinople. After the funeral of his first son, Herman, Setrag Timourian and his entire family moved to Constantinople on March 18, 1896, exactly four months after the massacres of Armenians in Kayseri.

One of Timourian’s great dreams was to ensure a proper education for his sons. During the family’s years in the capital, two of his sons, Onnig and Anarig, received their primary education and were then accepted into the city’s famous Roberts College. Two years later, Onnig was forced to abandon his studies to help his father run the family store. After graduating from college, Anarig obtained a pass to leave the country by bribing an official, and went to continue his studies in Oxford, England. After graduating, he wished to move to America. Kalenig studied at the Iskudar American Women’s College, graduating in 1911.

The Timourians’ three younger songs, Herman (the second of this name), Haygalous, and Levon were born while the family lived in Constantinople. Setrag first visited America in 1910, already planning to leave the Ottoman Empire and move there, and opened a store selling antiques. He sent Herman to America immediately after the outbreak of the Balkan War. Haygalous and Levon remained in Constantinople to finish their studies. Timourian left the Ottoman Empire for the final time in October of 1912, alongside Nazen and his daughter, Kalenig.

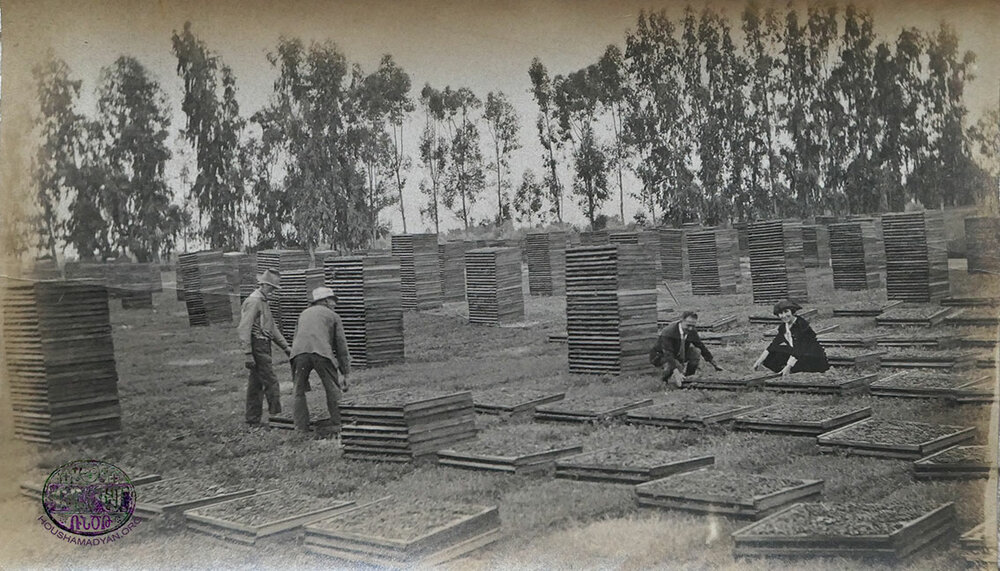

The family’s business thrived in America, because even after moving to New York, Timourian could import Persian carpets and rugs with the help of Onnig. After the First World War broke out, the difficulties in importing merchandise dealt a heavy blow to the carpet trade. Due to the condition of his health, Timourian could no longer live in New York and wished to move to California. Acceding to the wishes of his family and friends to do so without delay, in 1918 he moved to Fresno with his family, where he bought a property that included a house and a vineyard.

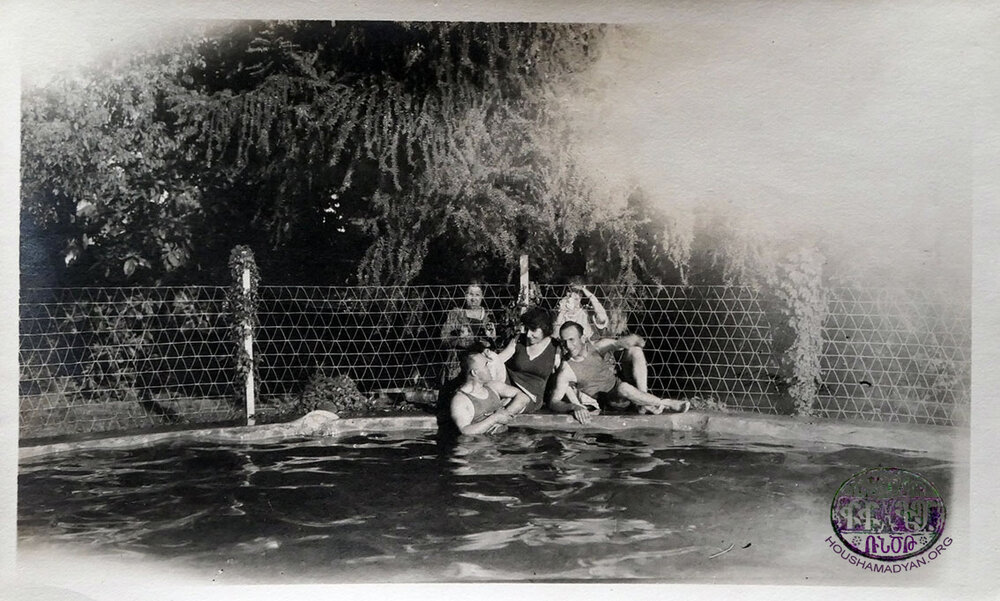

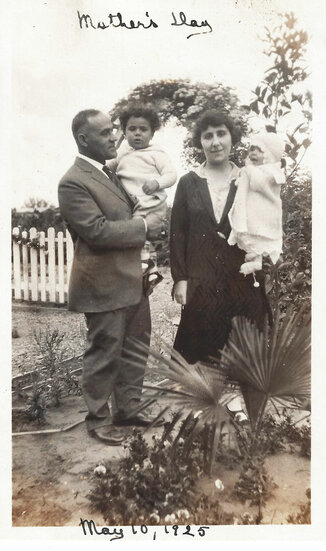

According to the family history, Kalenig named this property “Golden Dawn.” According to Nazeli, the property also included a pond, a swimming pool, and a tennis court.

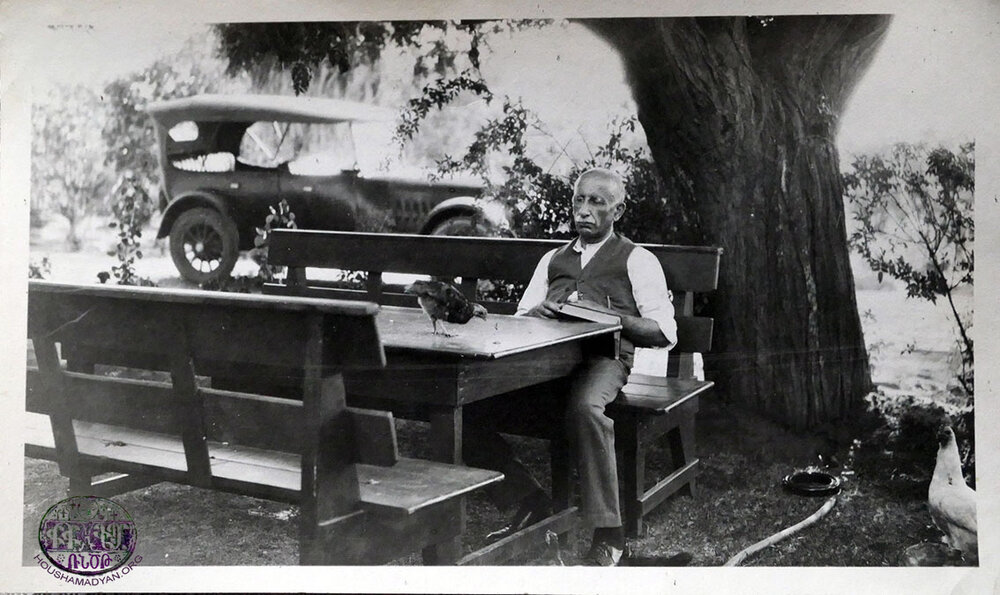

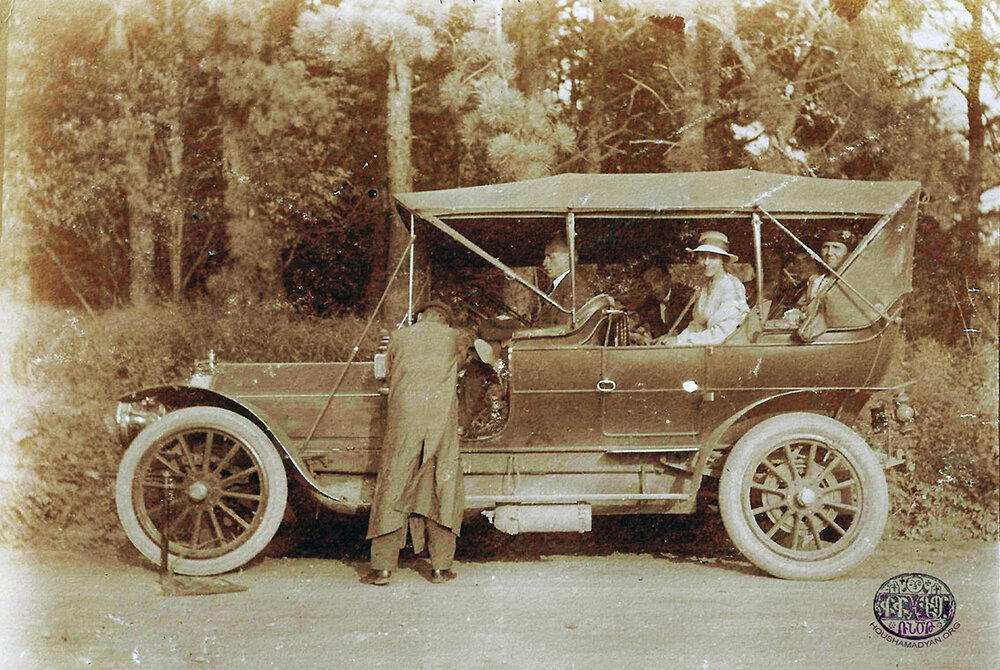

During this time, agriculture was thriving in Fresno, and the Timourians enjoyed significant success in this field. According to the family history, Setrag Timourian was the first person in the Fresno area to own his own automobile.

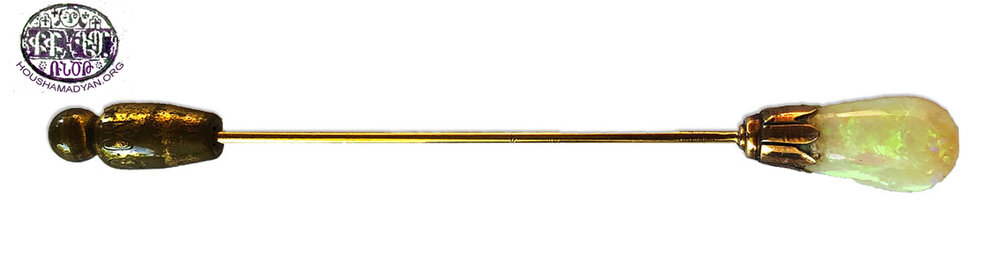

A melchior box with the carved image of Saint Kevork (Saint George). It contains pieces of other ornaments.

In 1922, Setrag and Nazen’s daughter, Kalenig, married Asadour (Asdour) Elmassian, a Kharpert/Harput Armenian and an attorney. In that same year, a few months after Kalenig’s marriage, Nazen fell ill with cancer and died. This was a heavy blow for Setrag. By this time, his sons had moved to California, where Levon studied law and Haygalous studied civil engineering. Anarig had already passed away.

Soon, for various political and financial reasons, the agricultural sector in Fresno experienced a decline, as did the trade in antique carpets and other antique items. Setrag Timourian called this the third and final phase of his life. He had lost his mate, his children were busy with their own lives, and he was forced to sell his house and vineyard in Fresno to pay off mortgages. From 1932, he lived with Kalenig’s family.

Prior to the family settling down in Los Angeles, Setrag Timourian lived with his daughter’s family in the city of Pasadena, California. After the end of the First World War, the family had opened an antiques and antique carpet store in the city. Among other items, they sold rugs and pillows from Baluchistan. One of these pillows, alongside a copper tray from the 18th century and various other items, are kept to this day in Nazeli Elmassian’s home.

In 1937, with the financial assistance of Setrag Timourian, Kalenig and her family purchased a house in Los Angeles. To this day, Nazeli Elmassian lives in that same house. Setrag Timourian considered himself a devout and good Christian. In the final years of his life, he was a member of the parish of the Masis Church, located not too far from the family home, and served as an acolyte. In the absence of the reverend, he delivered sermons. He served in the church until his death in 1946.

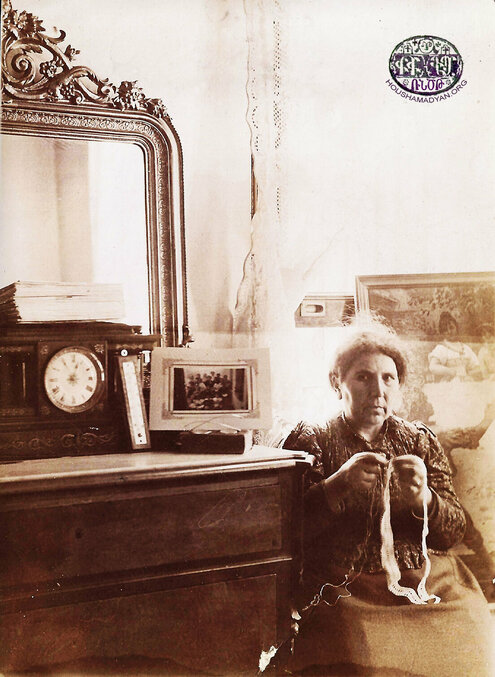

Nowadays, any visitor to Nazil Elmassian’s house has the impression of entering a small, unique museum. Everything in the house has been left as it was in the 1930s. Nazeli’s parents’, brother’s, and grandfather’s rooms have been preserved exactly as they were, including the furniture. In the corner of Setrag Timourian’s old room is the very same desk at which he sat to write his memoirs.

The Stewards of the Telfeyan-Timourian-Elmassian Legacy

The principal stewards of these families’ historical legacy have been Nazen, her daughter Kalenig, and her granddaughter Nazeli. Thanks to these women, this amazing collection has been preserved for many decades and has been passed down to us.

Nazen’s only daughter, Kalenig, was an educated and erudite woman. Nazeli remembers her mother as a graceful, broad-minded woman who had a keen and sharp intellect and cultivated various interests. She spoke several languages, could read and understand Classical Armenian, and wrote poetry. She was a skilled pianist and a wonderful singer.

During the years that she spent in New York, Kalenig took classes in social work. After moving to Pasadena, and for many years afterwards, she worked as a social worker, motived by her love of people. During the years of the Second World War, she worked in the U.S. Bureau of Censorship as a translator. She was interested in childhood education, and often delivered lectures organized by the groups of which she was a member. She was an active member of several church parishes, as well as the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), and worked tirelessly for the betterment of the Armenian community.

At a young age, and following the advice of her mother, Nazeli enrolled in the United States Navy Medical Corps. Upon returning from service, she continued her education and worked as a teacher in a school for deaf-mute children. In 2020, she celebrated her 96th birthday. She still has a valid driver’s license, and she never married. To this day, she preserves the family collection that her ancestors passed down to her with the utmost care.

We can only imagine what would have happened if these women had not hauled their family’s possessions from country to country. We would have had nothing to say about the Telfeyan-Timourian dynasty and its history. Thanks to this collection, Armenian cultural relics of great value have survived the ravages of time. Without these items, the history of a family that played an important role in the history of the Armenian nation would have been lost irretrievably. The items and photographs that these women have preserved are the living witnesses and the vessels of their families’ histories. These women not only kept alive the dynasty’s past, but also created an invisible, but solid bridge between the present and the past, thanks to which we can “travel” in time and acquaint ourselves with the important events and turning points of the history of Kayseri Armenians. With this “bridge,” these women have also bequeathed to us a national and cultural legacy, which originated in Kayseri but evolved over the decades and in various parts of the world. This legacy doesn’t just belong to Kayseri Armenians or to the Armenian nation – it is of universal value.

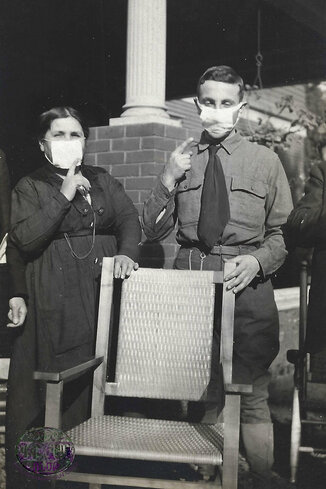

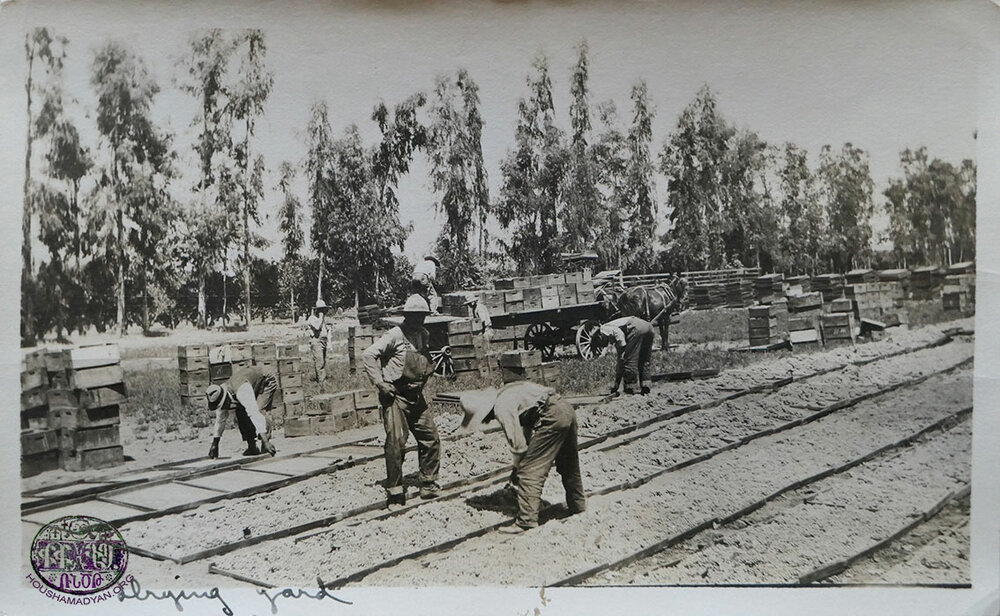

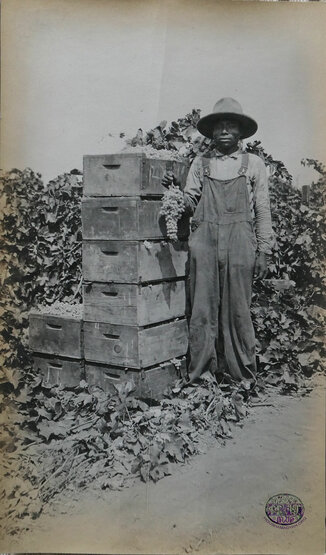

The Timourians in Fresno

Here, we present numerous photographs of the Timourian family taken during the years they lived in Fresno. The photographs are dated between 1918 and 1920. As they show, the family was engaged in agriculture at the time.

- [1] Telfe [or telve] is the Turkish word for coffee grounds.

- [2] For more on Movses Telfeyan and his family, see S. Khachmanian’s article at https://www.houshamadyan.org/en/oda/americas/movses-telfeyan-collection-usa.html.

- [3] Setrag Timourian wrote his memoirs in the final years of his life. In addition to details on his personal and family life, the memoirs provide valuable information on the Armenian merchants of Kayseri and their work. Timourian wrote in Armenian-lettered Turkish. Later, another member of the family, Hagop Temirdjian, translated the memoirs into English and distributed it to his relatives. The memoirs are currently being translated professionally.

- [4] S. Timourian’s memoirs.

- [5] Interview with Jennifer Telfeyan-LeRoy.

- [6] S. Timourian’s memoirs.

- [7] Arshag Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario [History of Armenian Gesaria/Kayseri], volume B, Cairo, 1937, pp. 2200-2203; also see the Armenian Dress and Textile Project.

- [8] Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, volume B, pp. 2201-2203. Also, the family history.

- [9] The family tree was prepared by Jennifer Telfeyan-LeRoy.

- [10] From our interview with Jennifer Telfeyan-LeRoy, we know that one of Garabed’s sons, Mihran, died in Kayseri at the age of three.

- [11] The dates of birth and death of some of the family members were determined according to the information provided by Jennifer Telfeyan-LeRoy.

- [12] Roland Telfeyan is Jennifer’s brother, and currently lives in New York.

- [13] Also mentioned in S. Timourian’s memoirs.

- [14] Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, pp. 2201.

- [15] Jennifer Telfeyan-LeRoy’s archives.

- [16] This rug was made in the Telfeyans’ factory in Kashan.

- [17] Interview with Roland Telfeyan.

- [18] Ibid.

- [19] Jennifer Telfeyan-LeRoy’s archives.

- [20] Arshag Alboyadjian, Badmoutyun Hay Gesario, pp. 2202-2203.