Nellie Miller Mann Archive

Author: Rosemary Russell

A Picture of Heroism

"I assure you, friends, had you been on the field and witnessed such conditions as I have, you would term it other than bravery or heroism. To have considered one’s own life precious in the face of desperate and dying multitudes would have been utter cowardice". [1]

Those are the words of Nellie Miller Mann, secretary to the Treasurer of Near East Relief (NER) in Beirut, 1921–1923. A graduate of Goshen College, in Goshen, Indiana, Nellie came in the humble guise of a secretary, willing to take dictation and to type as her contribution to the “most colossal child welfare [undertaking] in the history of the world.” [2] Among the several treasurers under whom she served were Ray F. Bender, of the Mennonite Church, and Stanley Kerr, author of The Lions of Marash.

Besides diligently tending to accounting and correspondence in the office, Nellie had the presence of mind to preserve her tenure with NER by taking photographs, a cherished hobby. She used photography to educate friends and family back home about the conditions she witnessed and those she heard about from co-workers and survivors, never imagining that her photographs would help establish the incontrovertible truth of the ongoing tragedy facing Armenian, Greek, and Syrian refugees.

Nellie Miller grew up in Elkhart, Indiana, and attended the Prairie Street Mennonite Church. She graduated from Goshen College in 1921. It might seem improbable that a young secretary would wind up documenting relief work in the Near East until one considers the inspiration for Nellie and other Mennonites to help rebuild cities and lives at the end of the Great War.

The Mennonite Relief Commission for Wars Sufferers (MRCWS) formed in Nellie’s hometown of Elkhart, Indiana, in 1917. The thought had been to establish a Mennonite mission in the Near East. However, an expedition made it evident that existing infrastructure adequately supported ongoing relief work. Thus, the Mennonite Church thought it wiser to cooperate with NER instead of establishing an independent endeavor. [3]

1) Circa 1922

A caravan transports orphans out of Turkey to orphanages in Lebanon. This iconic moment was likely captured by a Near East Relief worker.

(Courtesy of Mennonite Church USA Archives, Elkhart, Indiana)

2) Circa 1922

Refugees coming out of Turkey.

(Courtesy of Mennonite Church USA Archives, Elkhart, Indiana)

That this relief commission was born in Elkhart harkens back to the support of several missionaries from north-central Indiana, beginning with Rose Lambert in 1898. She founded the United Orphanage and Mission in Hadjin, Turkey. Her sister Norah had attended Nellie’s church as a young girl, and Nora, too, had taken courses at Goshen College. In late 1914, at the start of the war, all of Elkhart waited news of Norah’s safe return after a perilous escape from Everek, Turkey. [4] Just five years before those apprehensive days, Nora’s older sister Rose made headlines during the siege of Hadjin in 1909 when anti-Armenian massacres erupted throughout the vilayet of Adana. [5]

Besides the courageous Lambert sisters, there was Adeline Brunk who came from Elkhart. She died in Hadjin only six weeks after her arrival. Henry Maurer, one of two Americans killed during the Adana Massacres, lived in Goshen before he went to Hadjin. Katherine Bredemus, from nearby South Bend, was yet another missionary from northern Indiana who served the United Orphanage and Mission, assisting orphans in Hadjin and in Cyprus.

When Nellie was fourteen years old (1911), the Prairie Street Mennonite Church welcomed as speakers Rose Lambert and her guest Bishop Moushegh Seropian, ex-Prelate of Adana. According to the local paper, Elkhart had “of late years been much interested in the welfare of the Armenians,” and expressed the hope “that the opportunity they […] had of seeing and hearing Bishop Seropian” would leave a lasting impression. [6] Nine years later, Katherine Bredemus who had returned to Hadjin after the Armistice, was trapped there amidst the final, fateful battle of that Armenian town. South Bend Times reported the disturbing circumstances. [7] At that time, Bredemus worked among the repatriated orphans.

Perhaps the event at her church in 1911 made a profound impression on Nellie. Most certainly, the heritage of Elkhart’s support of Armenian orphans and several Indiana missionaries played an important role in shaping her decision to set out for the Near East as a relief worker.

At the end of World War One and at the direction of French authorities of occupied Cilicia, Armenian orphans were gathered and resettled in their native towns, many having been rescued from the homes of Turks, Kurds and Arabs. [8] Nellie’s arrival in Beirut in 1921 came only weeks before the Ankara Accord in which the French ceded to Turkey the very places to which orphans had been returned in 1919. The herculean task of safely evacuating several thousand children was about to begin. [9]

In November 1921, the month following the Turkish-French agreement, Nellie’s correspondence begins recording the influx of Armenian refugees fleeing Turkey. Letters during 1922 express ongoing concern for nearly 7,000 orphans in Ayntab, Marash, Mardin, Diarbekir, Ourfa and Harput/Kharpert. “Still 1,200 orphans in Marash,” she wrote on 19 February. [10] By mid-April, 300 Marash orphans and 130 orphans at Ourfa had been safely removed. The Turkish government would not allow the mass evacuation of the children. Therefore, relief workers were forced to “send out several with each family that comes out,” Nellie had explained in an earlier letter. [11] Finally, the Turkish government granted permission for the departure of all Armenian orphans, which set the mass evacuations into motion.

According to Nellie, a truck drove from Ourfa—where orphans from other stations were being gathered—to Jerablus. Many trips had to be made since the truck could transport only 20 children at a time. In Jerablus, the children boarded a train to Aleppo. Once in Aleppo, they slept before taking the 5:00 a.m. train to Beirut, not arriving there until midnight. Day after day, NER workers met these groups of beleaguered children and transferred them to the Ghazir (Lebanon) Orphanage as a temporary measure. [12]

The overwhelming task of safely conveying thousands of Armenian orphans and the valiant work of sheltering, educating and nurturing them was all vividly chronicled by the sensitive and astute secretary to the NER Treasurer in the Beirut office. Nellie both photographed and developed (in an improvised darkroom) her collection of over 200 photographs. Although she did not travel inside Turkey, she is to be credited with preserving pictures that others took at their stations in the interior.

David Mann recently paid this tribute to his mother: “She was a gifted and humble person with a desire and commitment to serve a group of people in great need. The fact that she left [for Beirut] while engaged to my father says something of her spirit of service and mission.”

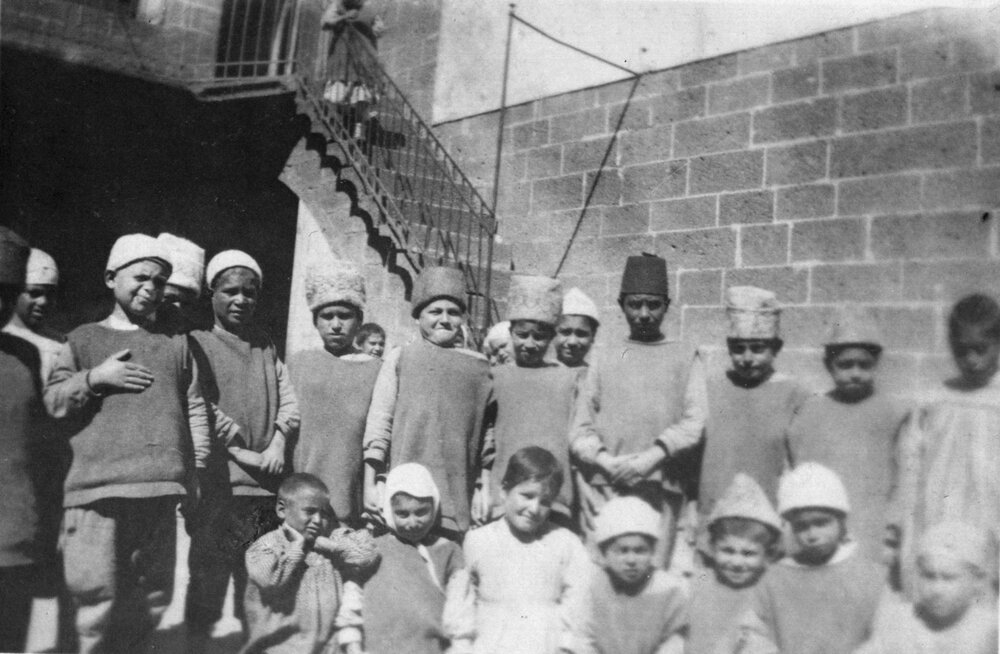

These orphans are confined while being treated for favus, a severe scalp fungus. The buildings in use by the NER had been a German orphanage for Armenian children before the war. Photo taken by H. B. McAfee, Managing Director of Near East Relief in Beirut.

(Courtesy of Mennonite Church USA Archives, Elkhart, Indiana)

The NER treated thousands of Armenian orphans for contagious conditions that resulted from malnutrition and poverty: head and body lice, favus (severe scalp fungus), scabies (chronic itching), and trauchoma (bacterial infection of the eye). The orphans in this picture would have been given baths, clean clothes, and medical treatment before placement in one of the orphanages in Syria.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

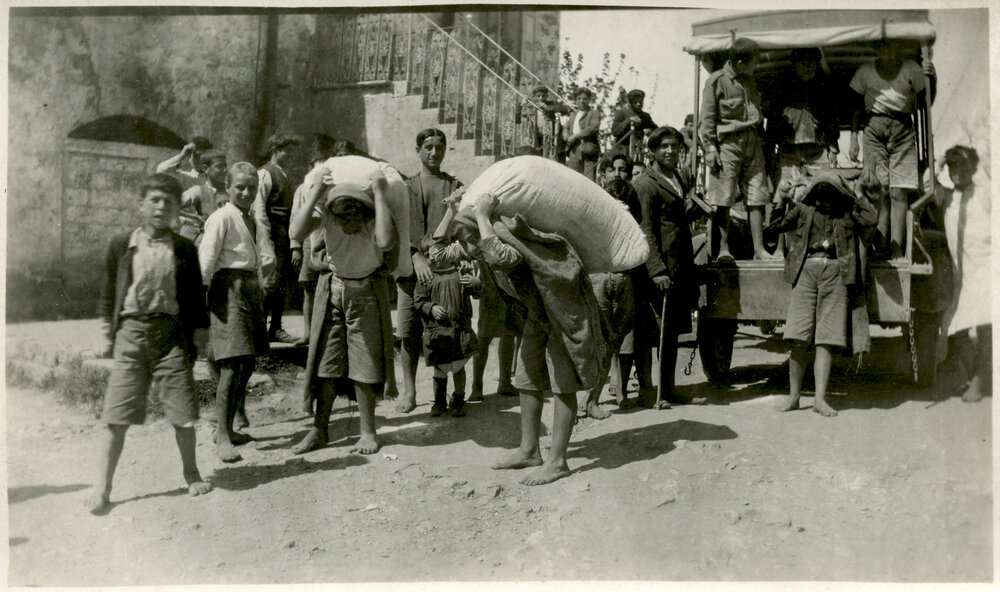

Orphans unloading supplies from Beirut NER truck. Upon this visit, Nellie wrote to her fiancé, "I doubt whether you could find a group [of boys] in America [...] as we have in Jebail (Byblos) and Antelias who are any more manly, courteous, enterprising and intelligent than these boys are."

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

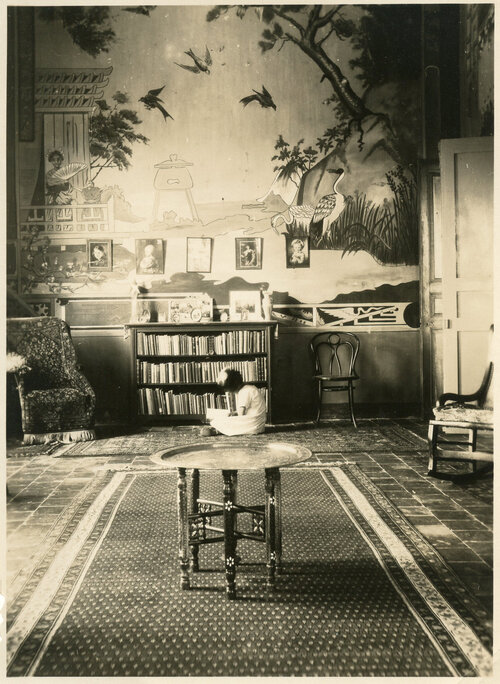

1) The building in the distance is the Birdsnest, located south of Beirut. Once the opulent home of a late pasha, it became the orphanage where Maria Jacobsen cared for 400 of the youngest orphans, nine years old and under. Nellie loved to visit here.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

2) Armenian orphans on their way to Sunday school at Shimlan – a village in the mountains in Lebanon. At that time, Martha Frearson, an American missionary who had run an orphanage in Aintab for several years, was in charge of these boys.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

The building in the distance is the Birds' Nest, located south of Beirut. Once the opulent home of a late pasha, it became the orphanage where Maria Jacobsen cared for 400 of the youngest orphans, nine years old and under. Nellie loved to visit here.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

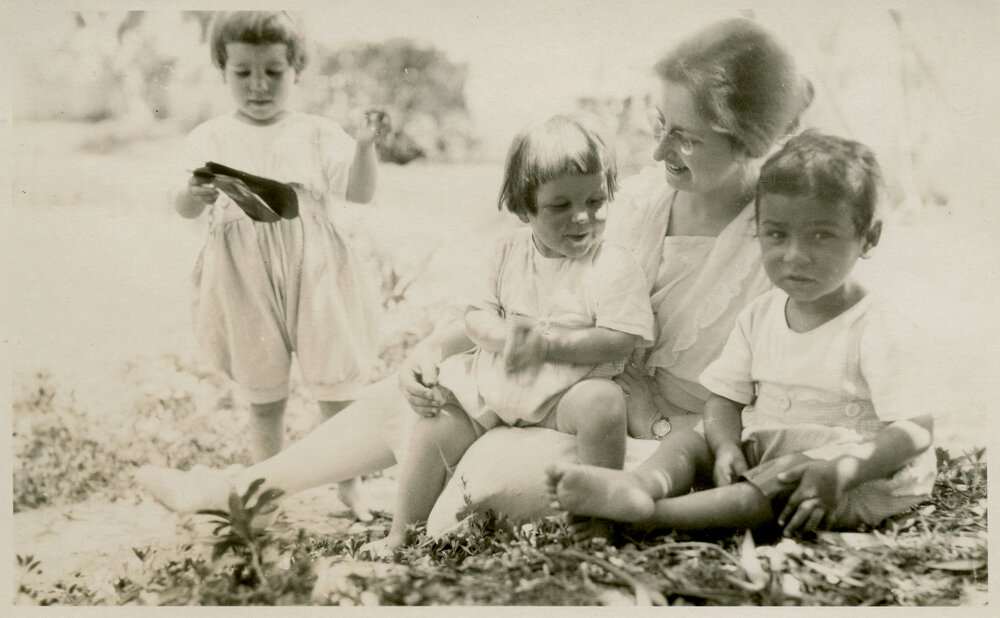

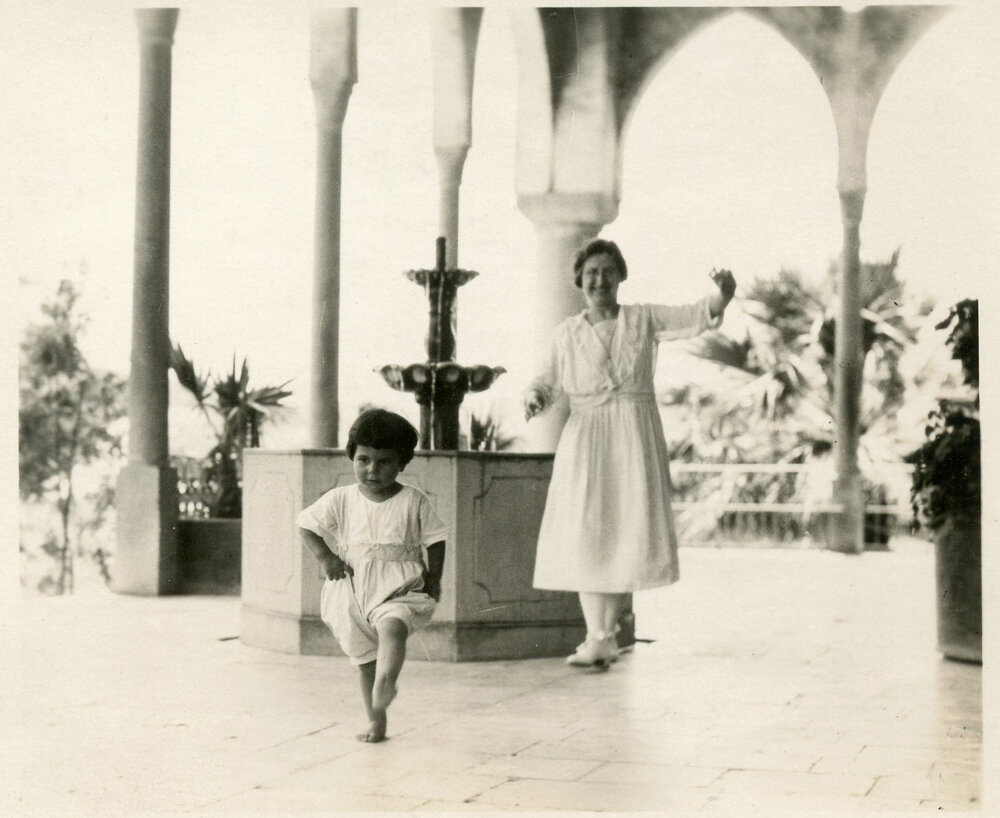

1) and 2) Maria Jacobsen, washes the children at the fountain. She made sure the orphans were clean and tidy — hair combed, clothes laundered, faces and hands washed.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

3) Nellie Miller Mann and an orphanage staff member oversee a meal on the veranda.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

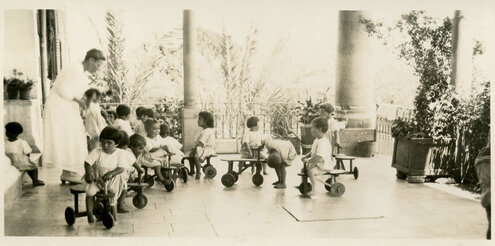

Maria Jacobsen (left) and Nellie (right). Miss Jacobsen, surrounded by seven orphans, receives a kiss from one. According to Nellie, Jacobson possessed a good combination of disciplinarian and affectionate foster mother. The young children's new tricycles made by the boys of the Maameltein Near East Relief orphanage, north of Beirut, can be seen in the photo.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

1923, Birds' Nest, Saida/Sidon

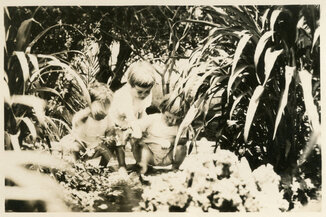

1) and 2) Ibrahim, left. Anna, far right. Every afternoon, a few orphans took their turn in the lush garden among hollyhocks, blooming pomegranate trees, roses, violets, daisies, poppies, and a host of other flora and fauna.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

3) Nellie (on left) in the beautiful garden beside the orphanage.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

Mornings were busy at the Birds' Nest. Older girls bore the responsibility of putting away beds, setting places for breakfast on the lawn, washing and dressing the babies, sweeping the courtyard with palm branches, and scrubbing the floors. If they finished their work ahead of time, they were allowed to play until the start of school.

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

From her desk in Beirut, Nellie Miller Mann watched refugee children file past, wearing nothing more than gunnysacks and rags, many covered in sores. At the idyllic Birdsnest, she found solace in the voices of happy, healthy children, time spent in the garden, and a spectacular view of the western sky. “The most beautiful time of all is the sunset hour. No one can even imagine it.”

(Courtesy of the Mann family)

Special thanks to David Mann, Dorothy Mann Horst and David Horst, Nellie’s children and grandson. Thanks also to Jason Kauffman, archivist at the Mennonite Church USA Archives in Elkhart, Indiana.

[1] Cleo A. and Nellie Miller Mann Papers, 1920-2000. HM1-695. Mennonite Church USA Archives - Elkhart. Elkhart, Indiana. Series 2 Box 4 Folder 2. Talks about Near East Relief Work.

[2] ibid.

[3] Guy F. Hershberger and Atlee Beechy, "Relief Work." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 17 Jan 2017.

[4] “Miss Lambert Back from Troubled Asia,” Elkhart Daily Review 18 Dec 1914, p. 5.

[5] “Note from Miss Lambert Asks Help,” Elkhart Truth, 23 Apr 1909, p. 1. “Rose Lambert and Other American Missionaries Stationed in Hadjin,” Elkhart Truth, 27 Apr 1909, p. 4.

[6] “Adana Minister Speaker Here.” Elkhart Truth, 27 Mar 1911, p. 4.

[7] “Armenian City Seeks Relief from Allies,” South Bend Times, 30 Jun 1920, p. 4. “South Bend Woman Tells,” South Bend Times, 26 Dec 1920, p. 4.

[8] Vahé Tachjian, “Bref aperçu sur les orphelinates arméniens du Liban, de Syrie et de Palestine”, in Kévorkian/Nordiguian/Tachjian (eds), Les Arméniens, 1917-1939: la quête d'un refuge, Presses de l'Université Saint-Joseph, 2007, Beirut, pp. 82-91.

[9] David Mann, ed., Letters from Syria 1921–1923: Response to the Armenian Tragedy including Stories and reports written by Nellie Miller-Mann, Morgantown, PA, Masthof Press, 2013, pp. 57–105

[10] Mann, 57–58.

[11] Mann, 57.

[12] Mann, 76.