The Abrazian-Chekirdemian Collection – Buenos Aires

Translator: Simon Beugekian, 8/10/22 (Last modified 8/10/22)

These materials were provided to us by Sonia Cavallo, who lives in Virginia, United States. She inherited most of this information and these items from her grandfather, Assadour Abrazian. Some of the photographs and memory items presented here are currently in Sonia’s possession, while others are kept by her mother, Sonia Isabel, in Buenos Aires.

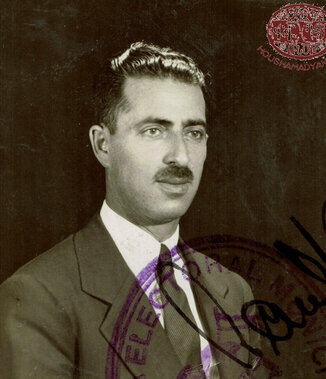

Assadour was born on December 8, 1909, in Hadjin. The date of his birth is not exact, as his relatives could only confirm that he was born sometime around the year 1909. Assadour himself chose the birthday of December 8, as this coincided with his favorite Catholic holiday, the Feast of Immaculate Conception. More likely, Assadour was born in the early months of 1909, because, as we will see, he was a newborn when he lost his father in April or May of that year.

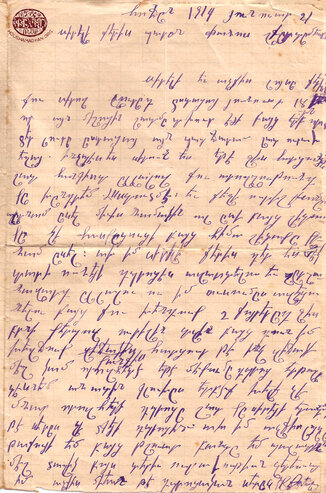

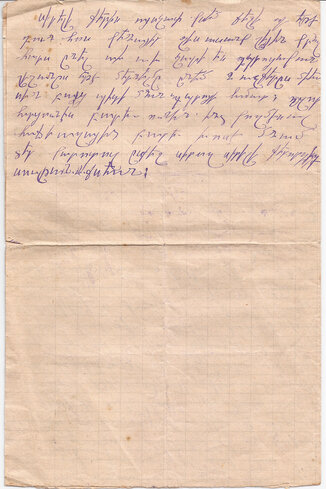

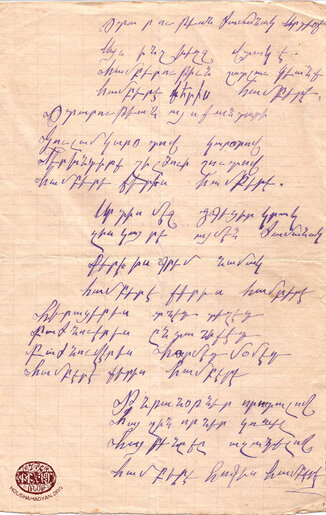

1), 2) A letter written by Sultan Abrazian to her uncle, Panos/Esteban Chekirdemian, who was already living in Buenos Aires. The letter is dated January 31, 1914, and was sent from Hadjin. In it, Sultan expresses her dismay at having been deprived of the opportunity to pursue higher education and having been forced to marry at a young age. She was about 13 years old when she wrote this letter. She doesn’t specifically complain about her marital life, but writes, “I am a queen, yet I am miserable. I am imprisoned in a palace.” What upset her most was being forced to leave school at a young age. She adds that if “you [her uncle] had remained here, they [her mother and aunt] would not have been able to marry me off like this.” Just a year later, Sultan was murdered on the road to Der Zor while pregnant with her first child.

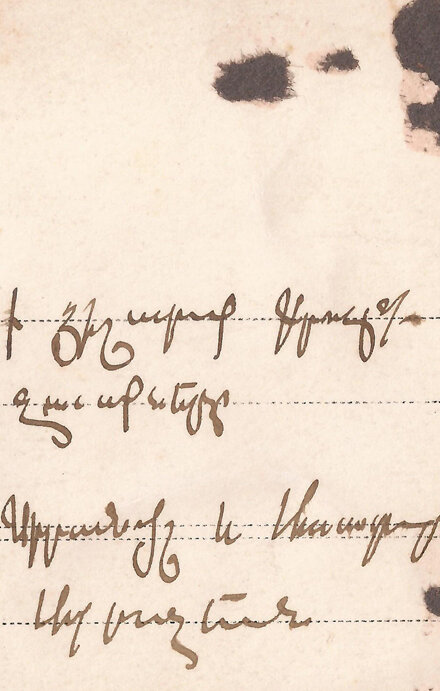

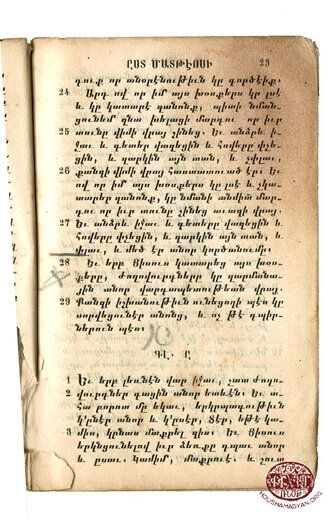

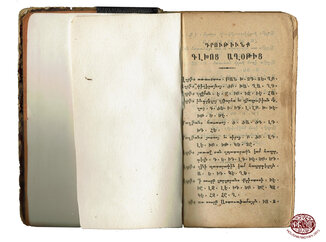

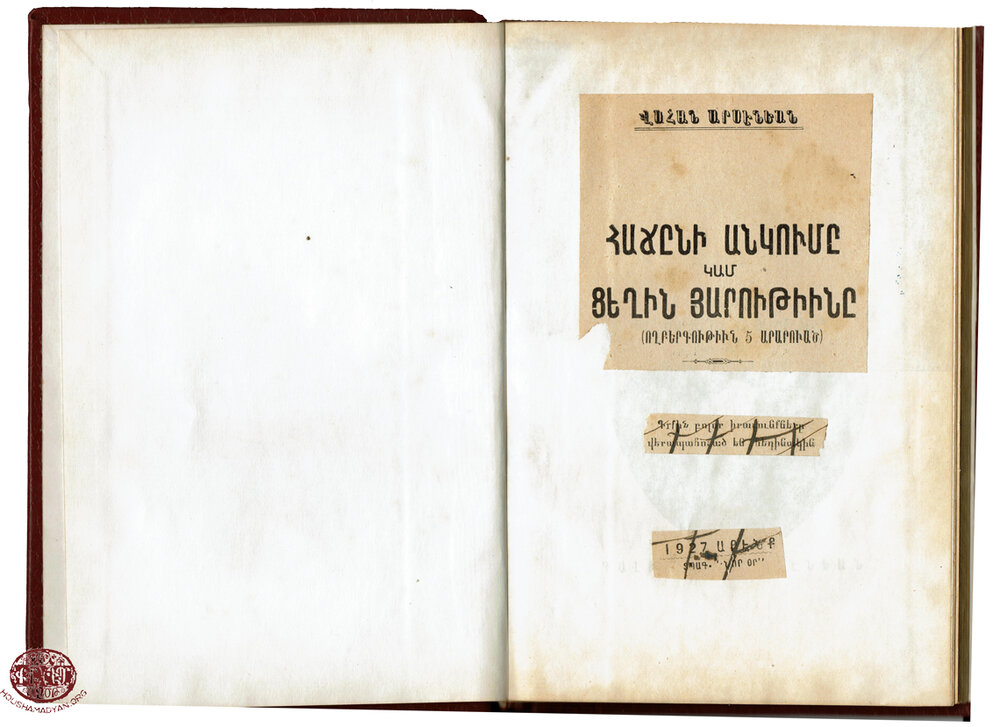

3) Most probably a page that was enclosed with Sultan Abrazian’s letter to her uncle. It is also written in Sultan’s handwriting. Here, she has copied an Armenian song, Odaroutyan ayskan dari, gou lam garodov, garodov [So many years of exile, I cry with yearning, with yearning]. Each stanza of the of the poem ends with the words Hampere, hokis, hampere! [Be patient, my dear, be patient!]. Sultan has substituted the words hokis [my dear] with keris [my uncle].

Assadour’s father, Haroutyun Abrazian, was the owner of a trading house in Hadjin. His business was successful, and he eventually became involved in the trade of grain. He bought a two-story house in the port city of Ayash/Ayaş, converting the first floor into a storage area and living with his family on the second floor. Haroutyun had a representative in Aleppo who made purchases on behalf of his business. Assadour remembers that when he was just a newborn, his father was murdered, and the family’s business was looted. Presumably, this event occurred during the anti-Armenian pogroms in the Adana area in April-May 1909.

Assadour’s paternal grandparents were Arakel and Yeranouhi (nee Penigian). They had one son (Haroutyun) and three daughters (names unknown). One of these daughters married Assadour Karatavoukian; another married Kel Hagopian; and the third married a Pilibosian. Arakel’s father was Pasha Panos Agha.

Assadour’s mother, Souna (Sonia), was the daughter of Garabed and Yeghisapet Shekherdemian. Garabed was a prominent citizen in Hadjin and had formerly served as the city’s administrator. The couple’s children included Souna, Mary, and Panos. In 1912, to avoid conscription into the Ottoman Army, Panos fled to Argentina, where he changed his name to Esteban.

Souna and Haroutyun married and had three children: Sultan (born in 1901), Siranoush-Dora (1906-2001), and Assadour (1909-2001). Siranoush was sent at an early age to the boarding school of the American missionaries in Ayntab. Sultan married when she was only 13 years old. She was killed in 1915 on the deportation march into Der Zor, pregnant with her first child.

In 1909, during the massacres of Adana, Haroutyun Abrazian and his family hid in their home in Ayash. They came out of hiding when a Turkish friend of theirs, whom they considered trustworthy, called them out. Haroutyun was killed right outside the family home. The other members of the family, including Souna, Siranoush, and the newborn Assadour, were saved by another Turkish neighbor. The family of this neighbor sent word to Hadjin, to Assadour Karatavoukian, who personally made his way to Ayash and rescued the surviving members of the Abrazian family, moving them to Hadjin.

In 1915, during the Armenian Genocide, Assadour and his family were deported. On the road to deportation, somewhere near Aleppo, Assadour’s mother, Souna, sent news to the local representative of her father’s trading house, who was a native Aleppine. The man answered the summons, and succeeded in rescuing the family from the deportation march, giving them shelter in his home. But the family barely had time to breathe a sigh of relief. The police soon raided the man’s home. The Abrazians were discovered, and this time, they were deported to the Bab concentration camp. There, Souna contracted typhoid fever, like many other deportees, and died. She was buried in a mass grave in the local cemetery. In his memoirs, Assadour mentions that refugees sick with typhoid were often buried alive by the local police.

Assadour’s tale of survival during the years of the Genocide is a veritable saga, characterized by death, violence, and good fortune. After losing his mother, he was lucky enough to find his grandmother, Yaranouhi, and other family members. But his grandmother also died. Assadour did not remember the cities and towns that he traveled through during these years of wanderings. After all, he was a mere child. But we know that his travels took him across Syria.

At the time, hunger and disease were killing countless numbers of Armenian refugees. Faced with these circumstances, Assadour’s family decided to leave him with two elderly Arab women, hoping that they would feed him and save him from certain death. In exchange, Assadour was to herd these women’s two cows. After staying in this house for six months, Assadour ran away and reached another Arab town. This time, he was taken in by the family of a sheik, for whom he herded calf. The sheik’s brother, who lived in the adjacent house, kept an abducted Armenian woman in his home. When she learned that Assadour was Armenian, she secretly gave him additional food. This was a great help for Assadour, whose adoptive family only fed him the bare minimum to survive. This same Armenian woman then helped Assadour escape. He joined a caravan and fled to Ourfa. There, Assadour made a living as a caretaker for a 25-year-old blind man. He stayed with this man for approximately a year. In the market of Ourfa, he became acquainted with a one-legged Armenian by the name of Hagop Haladjian, who was a tailor. We do not know whether Assadour made it to Ourfa during or after the years of massacres and deportations. Either way, we know that one day, Haladjian took little Assadour home, where the latter was accepted as a member of the family and given every form of care. He remained with this family for two years, and during his time with them, studied the Armenian alphabet and attended Armenian church.

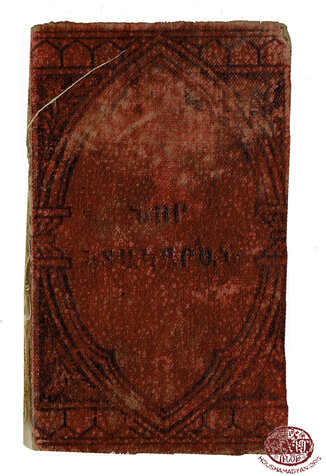

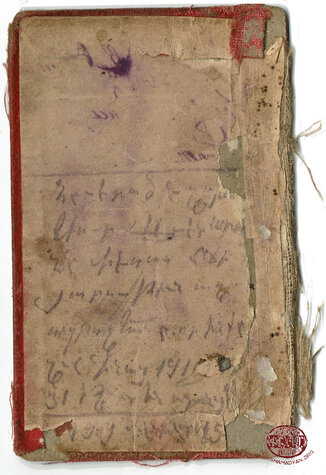

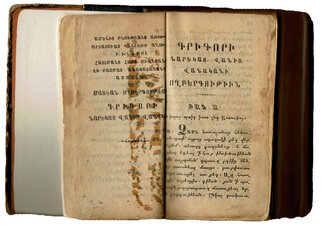

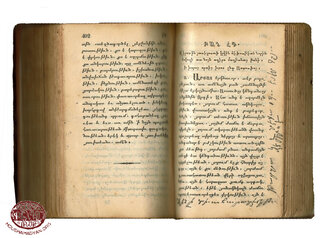

The New Testament. The date and location of the publication are unknown. The handwritten inscription on the back of the front cover indicates, though some words are illegible, that the Bible was gifted to Haroutyun Abrazian (Assadour’s father); or that it was gifted by him to another member of the family. This would mean that the Bible had been in the family since at least 1909, the year in which Haroutyun was killed.

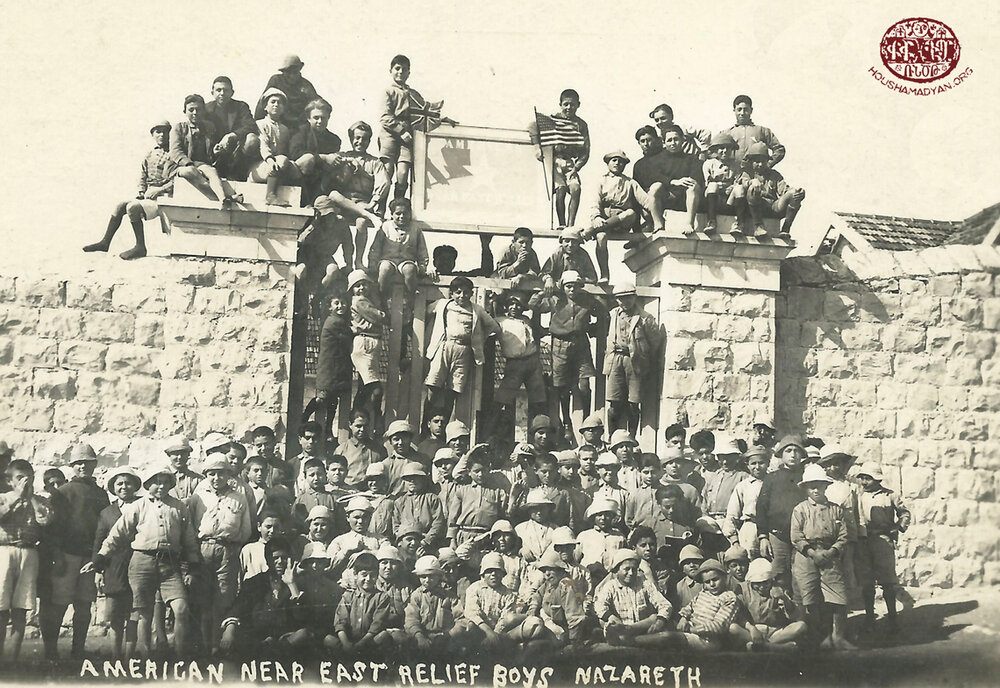

Later – and here, we can be certain that these events occurred after the Armistice that ended the First World War –, the Haladjian family entrusted little Assadour to the care of American missionaries, who brought him to Beirut. There, the missionaries would separate the orphans and send them to different American orphanages that had been established in various Middle Eastern countries. Assadour was sent to the American orphanage in Nazareth, in Palestine. During his time in Beirut, Assadour was reunited with a cousin, Sarkis, and another family member. They learned that he was being sent to Nazareth, and in turn, informed him that his sister, Siranoush, had survived the Genocide and was in Jerusalem. They also informed Assadour that his uncle, Panos/Esteban, was in Argentina. Later, Esteban learned that Assadour was alive via these same family members. In this way, Esteban and Assadour began exchanging letters. Esteban even sent Assadour issues of the Argentine Press (Arjantinian mamoul) newspaper, which he published.

Assadour arrived in the city of Nazareth in 1920. At the time, he was 11 years old. The superintendent/headmaster of the orphanage-cum-school was Haygazoun Keshishian. The other teachers were Americans. Assadour attended this school until 1927. There, he learned Armenian and English, as well as Armenian history and mathematics.

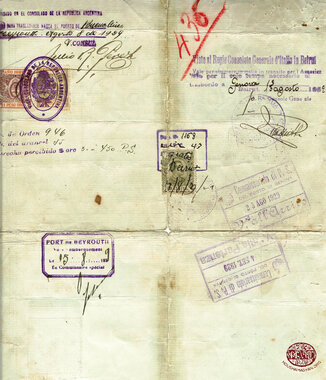

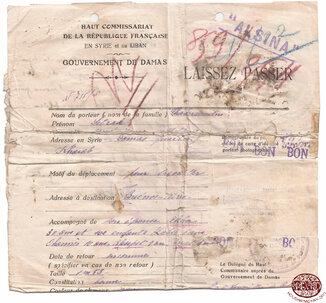

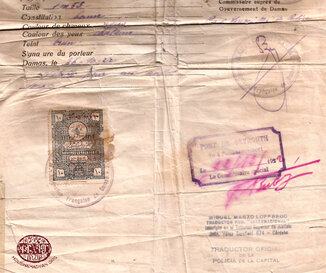

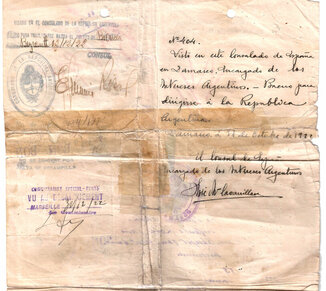

The laissez-passer that was provided to the Chekirdemian family by the Damascus District of the High Commissioner of Lebanon and Syria. The document indicates that the family was traveling to Buenos Aires. It lists their temporary address in Damascus. The other members of the family listed in the document are Acabi (the wife), Zabel, Ohannes, Yeghisapet, and Angela. The document was certified on October 26, 1922, in Damascus. The notations on the document also indicate that the Shekherdemian/Chekirdemian family left the port of Beirut on December 22, 1922; then arrived in Marseille and left that southern French port on December 30, 1922.

Immediately upon his arrival in Nazareth, Assadour affixed a note to the door of the Armenian church in Jerusalem, inquiring after his sister, Siranoush. But he received no news of her. Two or three years later, an Armenian man who wished to marry Siranoush wrote a letter to his friend, Haygazoun Keshishian (the headmaster of the orphanage of Nazareth), asking for his advice. The headmaster was aware of Siranoush’s story from Assadour. It was discovered that Siranoush had become a nurse, with a degree from the EEMS (Medical Missionary Society) at the hospital of Nazareth, which was located very close to Assadour’s orphanage. Haygazoun Keshishian invited her to the orphanage, and in this way, the two siblings were reunited after many years. They were virtual strangers, as Assadour had been very young when his parents had sent Siranoush to the American boarding school in Ayntab. Still, after this first meeting, Siranoush visited her brother every week, always bringing sweets as a gift for him.

In 1927, when Assadour was 18 years old, he graduated from the Nazareth School and began working for the Spinneys Limited company in Haifa, which was contracted to provide food for the British Royal Air Force units stationed in Palestine. The head of the company’s Haifa office was Hagop Haladjian (unrelated to the Hagop Haladjian from Ourfa who has already been mentioned in this article). Assadour was employed by this company from 1926 to 1929. He mainly worked as a motorcycle courier for his employer.

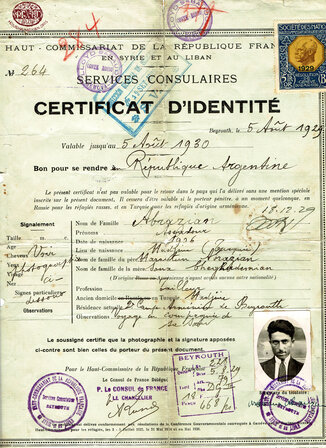

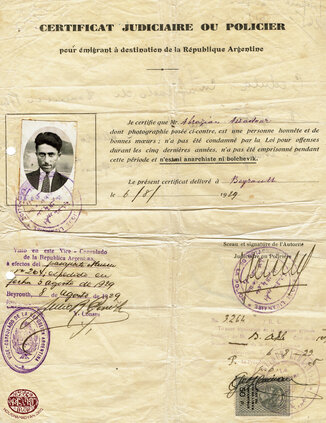

During these years, Assadour and Siranoush were invited by their uncle, Panos/Esteban, to move to Buenos Aires. Esteban also sent them the necessary ship tickets. From January to September 1929, Siranoush and Assadour stayed in Lebanon, where they made preparations for their departure. First, Assadour had to receive treatment for his eyes. Second, in his official papers, Assadour had to change his year of birth to his sister’s, while Siranoush had to change hers to his. In the case of young siblings traveling together, the brother had to be older than the sister, or they would not be allowed passage. A native of Hadjin, living in Beirut, was able to tamper with the siblings’ documents successfully.

Around this time, to earn a living, Assadour began working in the victuals procurement administration of the French forces stationed in Beirut.

Finally, the time to leave arrived. The ship left the port of Beirut in 1929, first making its way to Alexandria, and then Messina (Italy), Napoli, and Genoa. On the journey, it became clear that Assadour suffered from a serious illness of the eyes, which meant that he could not continue traveling. The siblings remained in a hotel in Genoa for two or three months while Assadour’s eyes were treated. The insurance company of the shipping line fully covered these medical expenses. Finally, with his eyes healed, Assadour, alongside Siranoush, boarded the liner Conte Rosso, headed for Argentina. Assadour remembers that along the journey, an album containing his stamp collection was stolen from him. It was not particularly valuable, but it was one of his very few personal possessions.

At the port of Buenos Aires, Assadour and Siranoush were welcomed by Esteban and his wife, Rogelia. For their first few years in Argentina, the two siblings lived with their uncle. Esteban was a butcher by trade. His shop was located in the San Cristóbal neighborhood, at the intersection of Entre Rios and Independencia avenues. The neighboring shop was also owned by an Armenian, the cobbler Daktadjian. For more on the Daktadjian family, see Houshamadyan’s Tagtachian Collection.

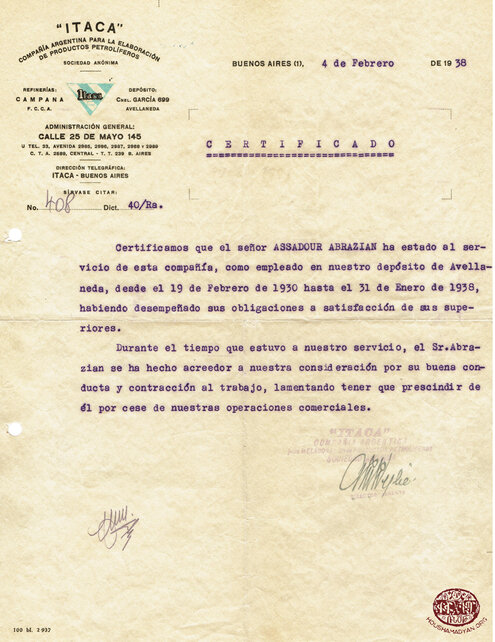

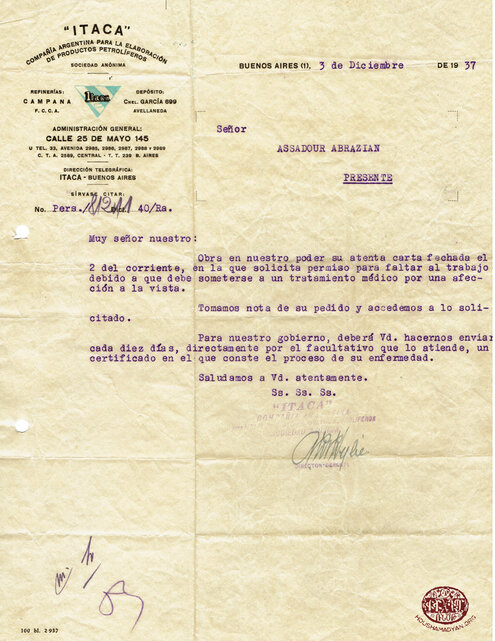

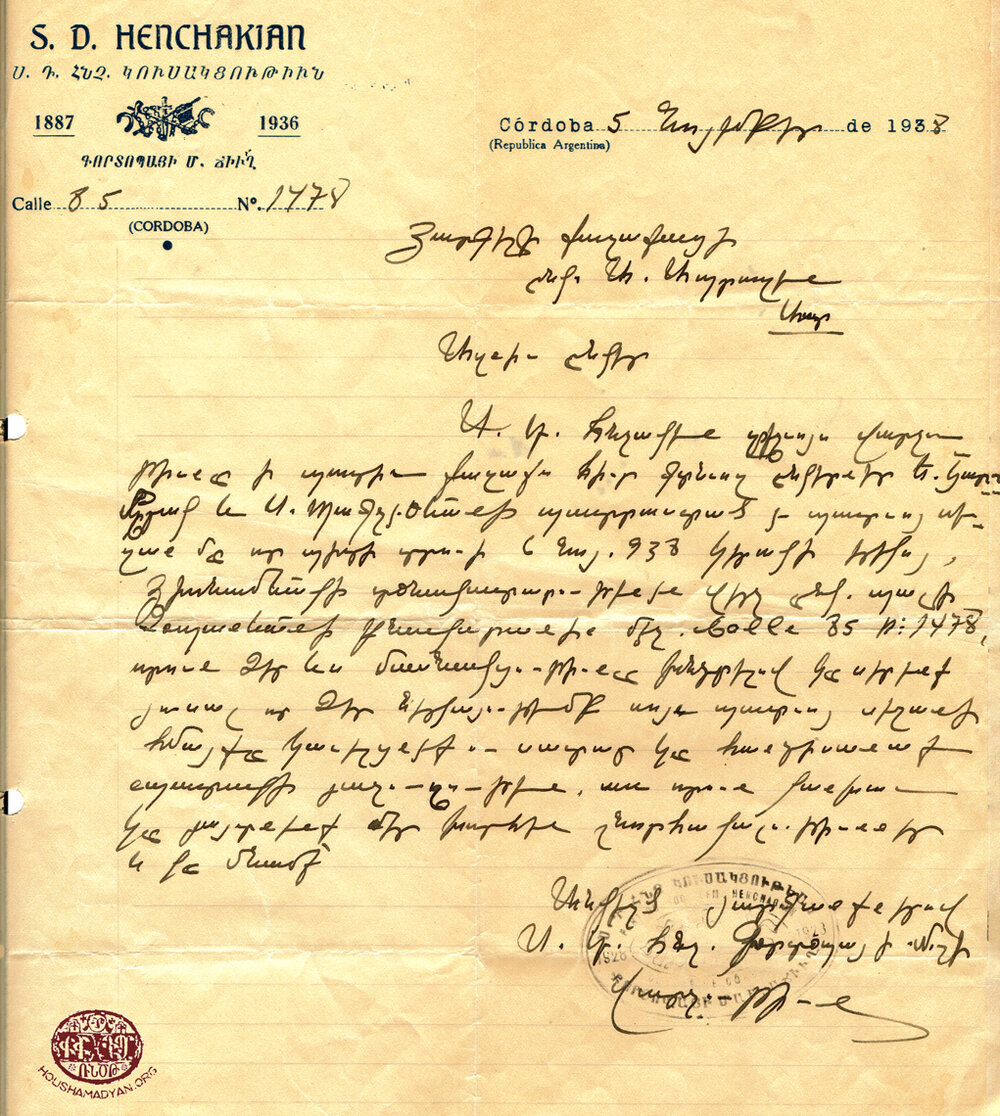

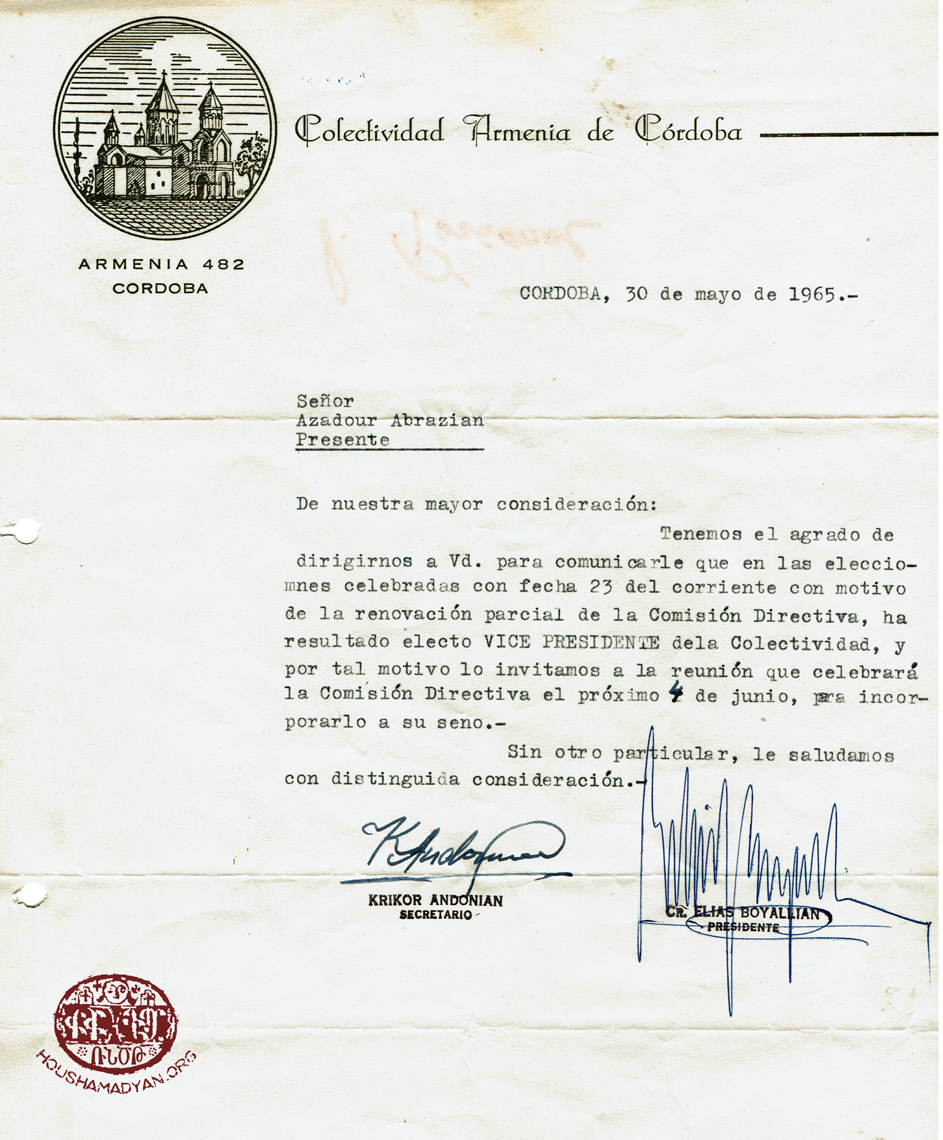

Siranoush-Dora worked at Belgrano’s American hospital. One of the patients at the hospital happened to be a manager of the Itaca transportation company. Siranoush asked him if her brother, who spoke fluent English, could find a job with the firm. The result was that Assadour was hired at a wage of 180 pesos per month. The pay was very satisfactory, and the work involved translating documents. Assadour worked for this company for seven years. He also actively participated in the life of the local Armenian community. He was a member of the Hunchak Party.

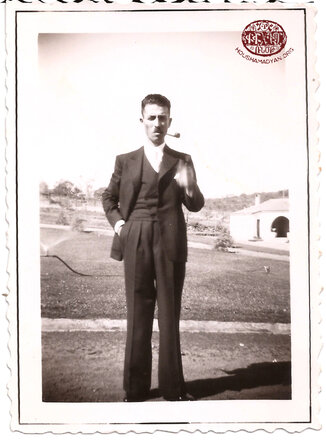

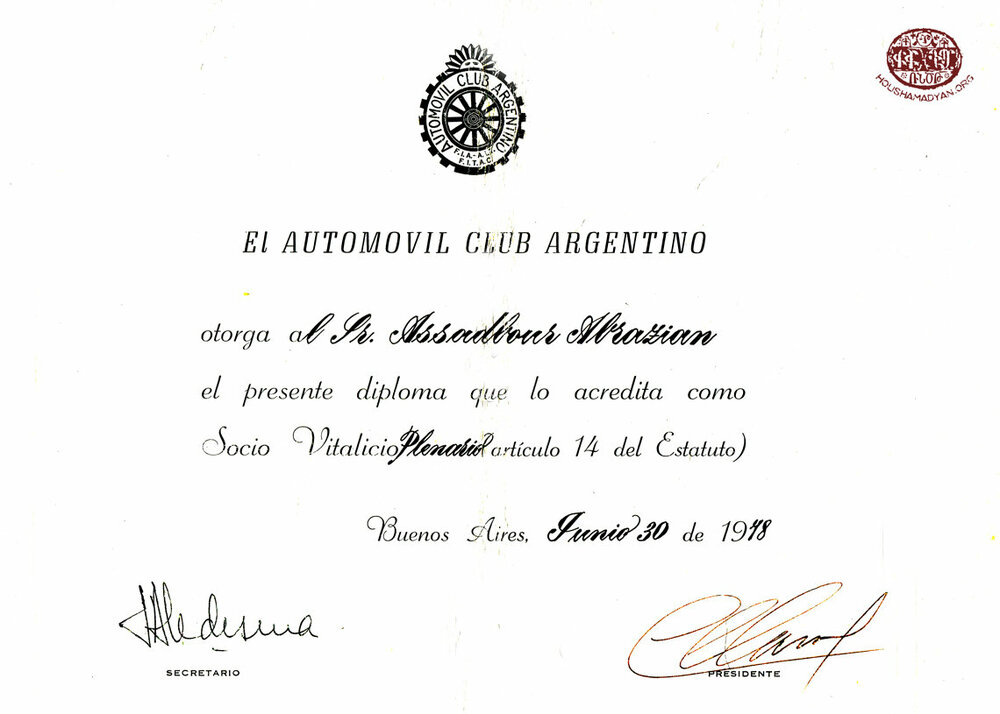

It was in Argentina that Assadour fell in love with dancing. Every Sunday, he would go dancing with his Armenian or Argentine friends in different neighborhoods – Pompeya, Paternal, Valentin Alsina, etc. One had to be dressed properly to gain admission to these dance halls. Assadour would always be dressed in patent leather shoes, striped gray pants, and a monogrammed silk scarf bearing the initials “AA” – Assadour (or Alfredo for the local Argentines) Abrazian. He always wore a gray hat, matching his pants and coat. Assadour loved dancing the fox trot, as well as rumbas and congas.

Just 15 to 20 years earlier, Assadour had been an orphan, living in strange places among strangers, herding cattle, often suffering from hunger, shuttled from one orphanage to another. But in Argentina, he enjoyed life to the fullest, dancing in the best clubs of Buenos Aires, dressed in the best possible attire. This transformation speaks to the indomitable willpower of a man who had survived the Genocide, and then had rebuilt his life and had thrived.

Every year, Assadour would take a holiday to Uruguay, where he was particularly fond of dancing and having a good time in the clubs of Montevideo. One year, Rogelia (Panos/Esteban’s wife) suggested that he go to Córdoba, rather than Uruguay. Assadour acceded, but as he later admitted, he had some reservations, given the large number of hospitals for tuberculosis patients that were operating in the city at the time. Assadour was worried of contracting the disease. In Córdoba, he stayed with Yester, a relation of his on the maternal side.

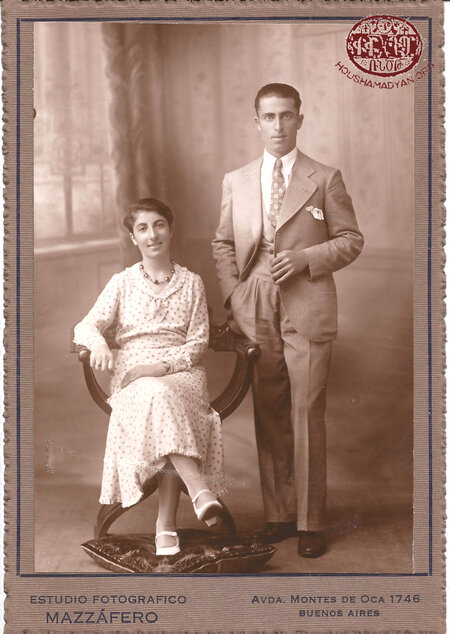

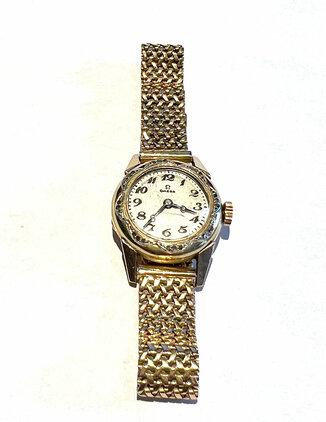

It soon became apparent that the family had convinced Assadour to travel to Córdoba to introduce him to a potential wife, whose name was Zabel/Isabel Shekherdemian (in Argentina, the surname had been altered to Chekirdemian). Assadour and Zabel’s first meeting went very well, but Assadour had to return to Buenos Aires for work. The affair continued via correspondence. For his betrothed, Assadour had a wedding ring and a gold watch encrusted with gems crafted by a jeweler, native of Hadjin, working out of the Barracas neighborhood of Buenos Aires.

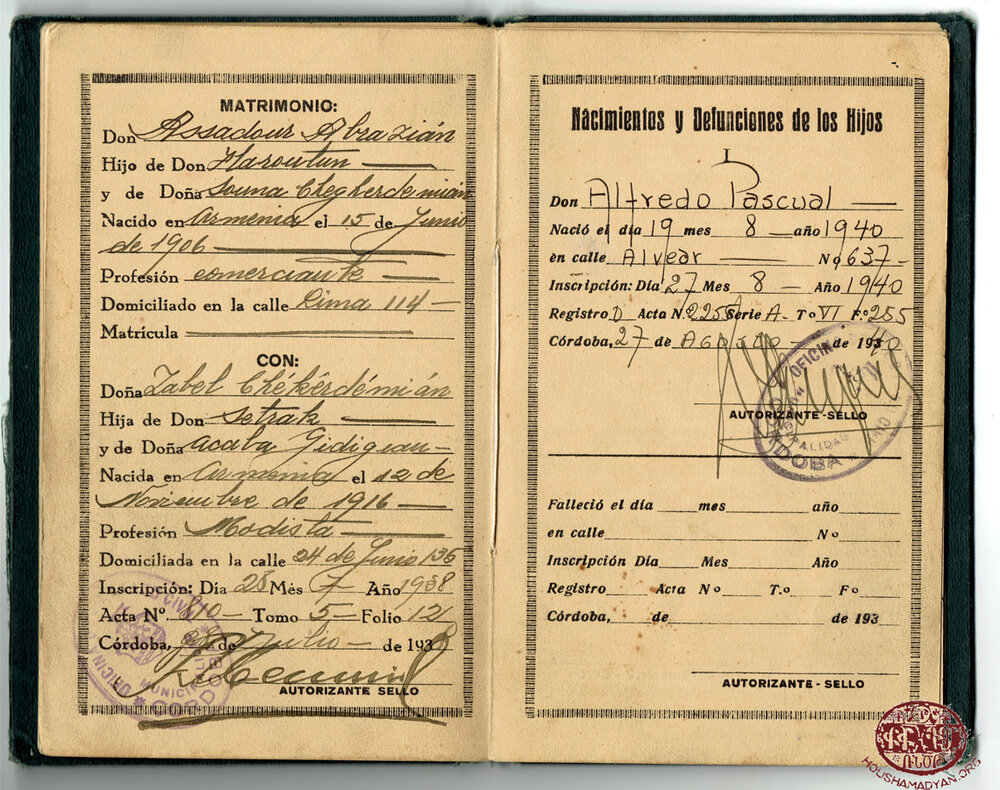

Eventually, nine months after their first meeting, Assadour returned to Cordoba and married Zabel, on July 30, 1938.

Zabel’s mother was Acabi Chekirdemian (nee Guedikian). She was born in Hadjin, in 1896. She died in Rosario, in 1978. Zabel’s father was Setrak Chekirdemian, who was also born in Hadjin, in 1882, and died in Cordoba, in 1955. Acabi and Setrak had six children: Ohannes/Juan (1912, Adana-1960, Cordoba); Zabel/Isabel (1916, Adana-2004, Buenos Aires); Isapet/Yeghisapet (later Danielian, 1920-2019, Rosario); Angela (later Hakimian, 1921-2011, Cordoba), Rina Tacuhi (later Dallorso, 1927-1978), and Maria (later Magarian, 1929-2018).

Setrak and Acabi were both born and raised in Hadjin. Later, Setrak moved to Adana, where he opened a textile store. When Setrak asked for Acabi’s hand in marriage, her parents objected to the prospect of their daughter leaving Hadjin and living in Adana. In view of this objection, Setrak bought a farm in Hadjin, settled back down in his native city, and thus was able to marry Acabi. Six months later, Setrak returned to Adana and resumed the management of his business. Of course, he took Acabi with him…

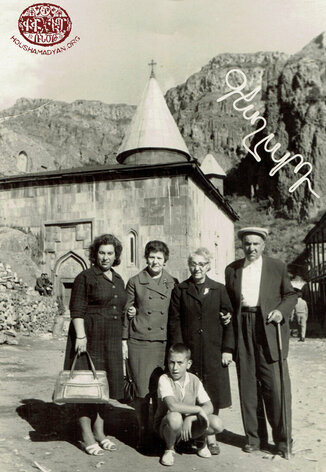

We don’t know much about what happened to the family during the years of the Genocide. We presume that a lucky few were able to remain in Adana and were not deported. It is a fact that Zabel was born in Adana in 1916. In 1921, during the final exodus of the Armenians of Cilicia, the family fled to Damascus. They then migrated to Argentina in 1923. On this journey, they were accompanied by Acabi’s two brothers (names unknown) and sister, Nassender Guedikian. The Chekirdemian family first reached Cyprus, and then proceeded to Argentina. They settled in the city of Cordoba, where Setrak opened a general store.

After Assadour’s marriage, his brother-in-law, Ohannes/Juancito, suggested that Assadour become a partner in his business. Ohannes’s business was selling lottery tickets. Assadour accepted the proposal. Together, they rented a shop outside the General Paz Cinema, from which they sold lottery tickets and various tobacco products, such as cigarettes, pipes, loose tobacco, etc.

Assadour and Zabel/Isabel had two children, Alfredo Pascual and Sonia Isabel. They were also blessed with eight grandchildren: Gustavo Alfredo, Fabian Antonio, Susana Carolina, Sonia Maria del Milagro, Eduardo Alfredo, Alberto Felipe, Tamara Anoush, and Jorge Assadour.

Assadour passed away in Buenos Aires at the age of 91, on January 5, 2001. Zabel/Isabel passed away on August 6, 2004 also in Buenos Aires.