Haratunian collection - Watertown, MA, USA

This collection was shared with us by Meline Haratunian Lachinian whose ancestors were from Karhad (present-name is Akıncılar, a small village in Sivas/Sepasdia and located just west of Zara), Bardizag (present-day Bahçecik, an Armenian village in Izmit, just east of Constantinople), and Erzurum/Garin.

Karhad (Province of Sivas)

Mariam Eghigian Haroutounian

Meline’s paternal grandmother, Mariam Eghigian Haroutounian, was born in Karhad in April 1906 to Zadig Eghigian (the son of Hagop and Marta Eghigian) and Tourvanda Soultanian Eghigian (the daughter of Garabed Soultanian and Narik Malkasian Soultanian).

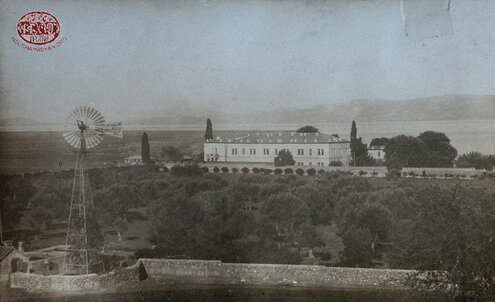

By the time she was two years old, both of Mariam’s parents had died and she was placed in the Swiss Orphanage in Sivas. That orphanage was founded by Swiss Protestant missionaries in 1897 initially to give refuge to the Armenian children of Sivas orphaned by the 1895 massacres.

Although the murders and deportations of the Armenians from Sivas began in July 1915, Mariam and the other Armenian orphans in the Swiss orphanage were somehow spared harm and allowed to remain in Sivas for a few more years. Several historic accounts mention that Mary Louise Graffam, an American missionary who was in Sivas before, during, and after the Genocide, likely was responsible for keeping the Armenian girls at the Swiss Orphanage safe. At the outset of the Genocide, Miss Graffam personally accompanied the first wave of the Armenian population from Sivas on their deportation in an effort to protect them; the Ottoman gendarmes eventually detained her in Malatya for several weeks and forced the Sivas Armenians to continue without her. [1] On the day of Miss Graffam’s return to Sivas, she learned that the Armenian girls from the Swiss Orphanage were to be deported the following day and she immediately negotiated an arrangement with the Ottoman Vali/Governor of Sivas that those girls would be protected from harm so long as Miss Graffam remained with them and took over the orphanage. [2] It was widely known among the Turks that Miss Graffam was in regular and direct contact with U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, which may have been an additional reason those Armenian orphans initially remained safe. [3]

According to historical sources, there were eighty Armenian orphans at the Swiss Orphanage who were permitted to stay behind in Sivas when the Genocide began. [4] In May 1916, the Ottoman Government ordered all of the remaining foreign missionaries in Sivas to leave, except for Miss Graffam who was assigned small quarters in the city compound with the orphans crowded in a house nearby and left unmolested under her guardianship. [5] In the years that followed, the orphans were forced to move within Sivas four more times, [6] and after the end of World War I, they came under the administration of Near East Relief.

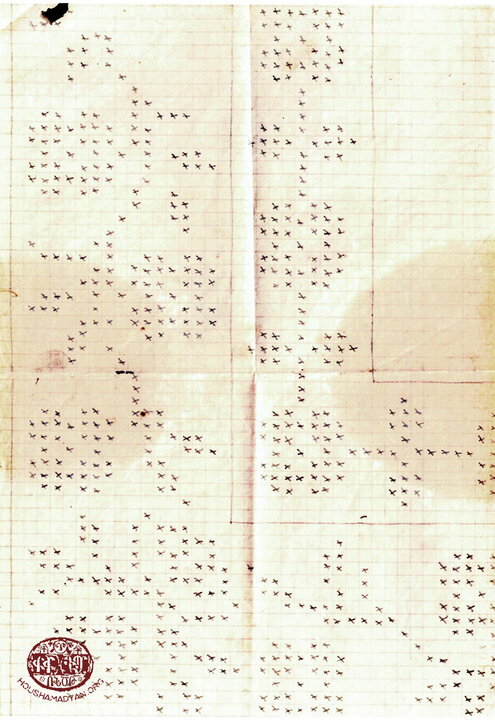

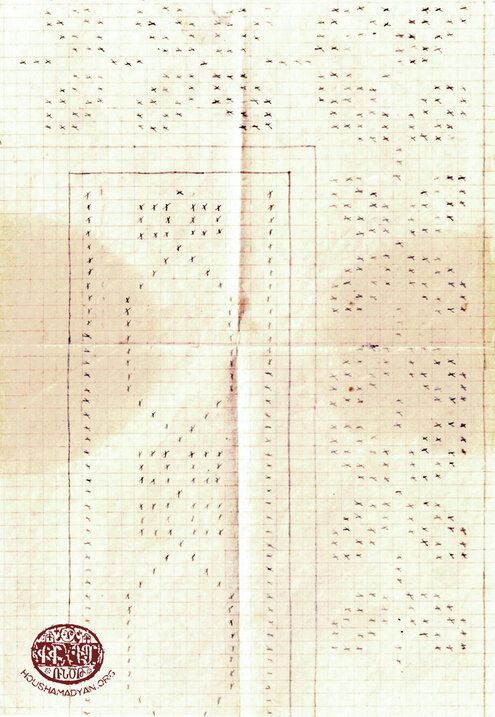

The entries in the Swiss Orphanage notebook demonstrate that, as of 1916 (when Mariam was ten years old), she and other Armenian orphan girls were still in Sivas and still being instructed in Armenian on Armenian subjects; this seems remarkable given the ethnic cleansing that was occurring around them at that time and probably was achieved through the courage and contacts of Mary Louise Graffam.

It is unclear exactly when Mariam and the other Armenian girls in her orphanage ultimately left Sivas. The Swiss Orphanage was still intact in Sivas as of 1917. [7] The Swiss Orphanage notebook ends in 1918 (when Mariam was twelve years old), which potentially could correspond to the end of her time in Sivas. For their safety, the Armenian orphans certainly would have all left Sivas by the early 1920s after Miss Graffam died in 1921 [8] and Near East Relief had transported their remaining Armenian orphans in Turkey to Greece, Lebanon, and other countries when the Kemalists came to power.

When Mariam left the Swiss Orphanage in Sivas, she went to an orphanage somewhere in northern Greece.

As was typical of the Armenian orphanages, Mariam and the other Armenian girls were taught skills to enable them to support themselves in adulthood. As a result, Mariam became quite adept at sewing, lacemaking, and other handiwork. The two photographs are examples of Mariam’s lacework likely made while she was in the orphanage or immediately thereafter.

All of Mariam’s extended family who lived in Karhad were killed in the 1915 Genocide. Mariam’s mother, Tourvanda Soultanian Eghighian, had had 17 siblings, 15 of whom survived infancy, but all of whom had died prior to, or during the Genocide except for four of Tourvanda’s brothers - Kerovpe and Serovpe Soultanian (who had emigrated to New York in 1896 and 1906 respectively) as well as Manas “Efendi” Soultanian (a principal of a school in Constantinople) and Roupen Soultanian (who also lived in Constantinople); none of Tourvanda’s sisters survived. Around 1926, Kerovpe and Serovpe learned that Mariam was still alive and made arrangements for her to come to New York. Mariam arrived in the United States on April 12, 1926 and initially lived with Kerovpe and Mania Soultanian.

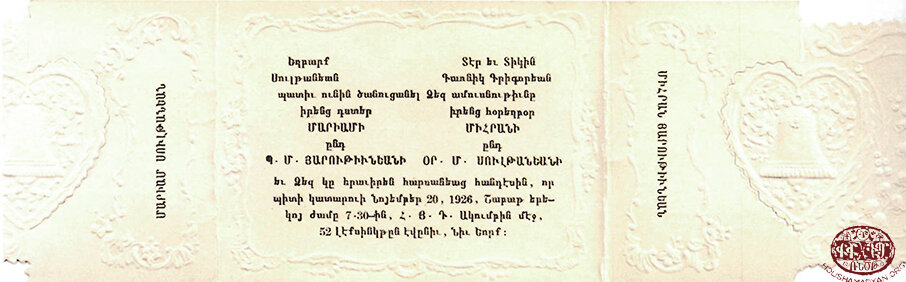

Shortly after Mariam arrived in New York (when she was 20 years old), she was introduced by a fellow Karhadtsi, Ovsanna Eghigian Krikorian, to a potential spouse, Mihran Eghigian Haroutounian, also from Karhad. Mariam and Mihran Haroutounian ultimately were married for more than 55 years.

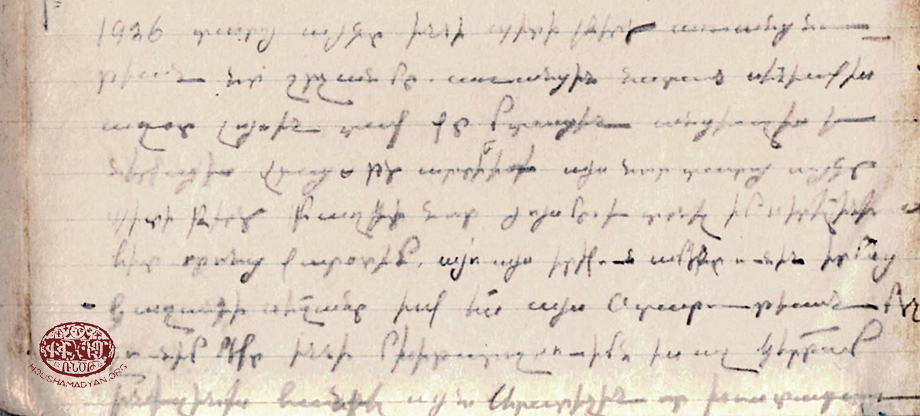

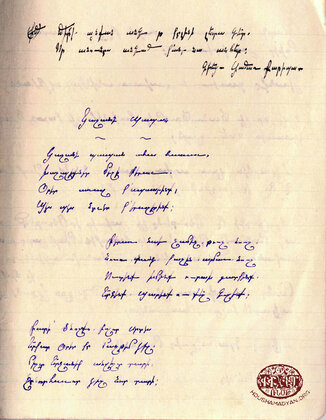

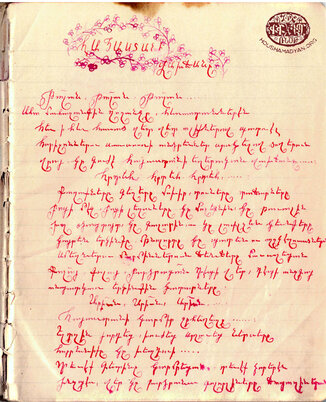

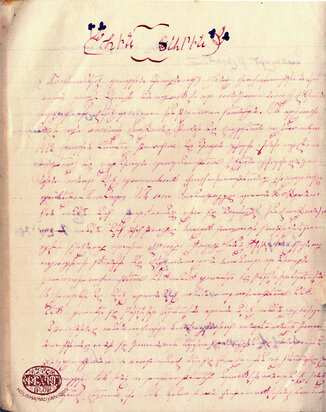

The Journal of an Orphan

Mariam Haroutounian (nee Eghigian) also left behind a journal, filled with entries covering her stay in the orphanage of Sivas/Sepasdia. The journal is currently in the possession of her granddaughter Meline.

At first sight, the journal seems to be relatively commonplace. Many of the pages contain poems or verse, evidently copied or transcribed into the journal. However, many of the personal notes in the journal were recorded at a crucial time in history. These entries provide valuable information of great importance, and motivated us to delve deeper into the journal’s pages.

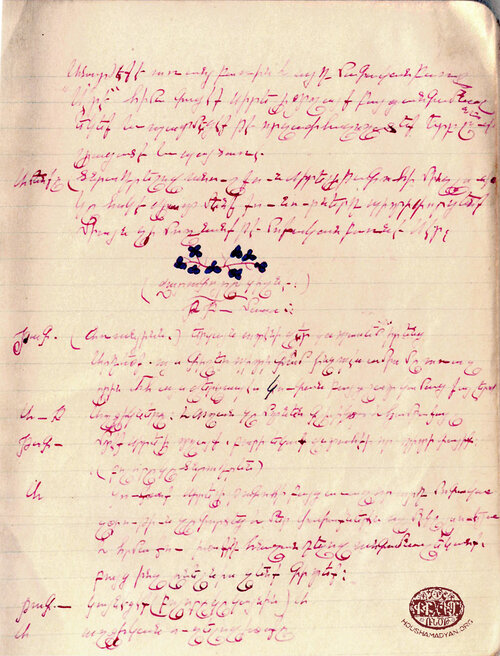

The cover of the journal reads “Eliza Donigian – November 2, 1916.” Therefore, the journal did not originally belong to Mariam, and Eliza was probably another orphan living in the Sivas orphanage. We do not know how the journal eventually passed into the possession of Mariam, but we do know that after the onset of the First World War she began writing in it. The entries include personal notes, as well as copies of poems and transcriptions of songs. On one of the pages, there’s a vertical note written in the margin – “The words of my beautiful sister are my keepsake of her.” The note is in Mariam’s handwriting, and was probably added in later years. The note seems to refer to Eliza and the journal. Unfortunately, we do not know much more about Eliza, nor do we know what fate befell her.

There is an assortment of poems and verse in the journal, mostly from popular contemporary writers – Bedros Tourian, Siamanto, Taniel Varujan, Avedis Aharonian. The works include Bedros Tourian’s poems Sev! Sev! [Black! Black!] and Ights Ar Hayasdan [A Yearning for Armenia]; Avedis Aharonian’s Harkank Kez [Respect to Thee], Ashoughe [The Minstrel], and Oror [Lullaby]; Siamanto’s poems Govgas [Caucasus] and Yes Yerkelov Gouzem Mernil [I Want to Die Singing]; and Taniel Varoujan’s Badkamavorners [My Delegates].

Other works copied or transcribed into the journal include Dikran Cheogurian’s Haverjanal [To Become Eternal]; Smpad Pyurad’s Hayasdani Vakhjane [The Demise of Armenia]; Hranoush Arshagian’s (1887-1905) Mahvan Mod [Near Death]; Shahan Natali’s Hatsi Asdvadze [The God of Bread]; Kamar Katiba’s Im Yerke [My Song]; and A. G. Bedigian’s Kritches Im Anoushig [My Beautiful Pen]. Some of the poems and verse have unknown authors, including Hin Darin [The Past Year]; Barignerou Takouhin [The Queen of Fairies] (play); Darakin Oughin [Darak’s Path]; Aghchig Chenk Ouzer [We Don’t Want a Girl] (play); Vorpn ar Sokhag [The Orphan to the Nightingale]; and Pnoutyan Latse – Sihoun [The Cry of Nature – Sihoun].

Notably, many of the authors whose works appear in the pages of the journal were killed during the Armenian Genocide (Siamanto, Dikran Cheogurian, and Taniel Varoujan). The orphans at the Sivas' Girls’ Orphanage, in their rooms, were making copies of patriotic, rebellious, and inspired lines of authors who, at that very same time, were being deported and murdered by the Ottoman authorities. This was a daring act of rebellion in and of itself, as we know that during the years of the genocide, many people (including adults, as well as school-aged boys and girls) were accused of keeping journals, diaries, or notebooks that contained nationalist literature. Naturally, the fact that they were in an establishment run by Swiss missionaries must have inspired the orphans with some courage, but in all likelihood, had the authorities laid hands on the notebook, the Swiss missionaries would have been unable to protect the girls.

Presumably, the girls did not copy the poems and verse from actually printed works of the above-mentioned writers. The orphanage, by then, had probably either destroyed those works, or had decided to store them, in order to preempt any searches by the government, and to avoid any accusations that would result. However, the orphans had clearly memorized these works. This assertion is reinforced by the fact that the orphans’ transcriptions of these works contain many grammatical and spelling errors.

The journal also contains several proverbs.

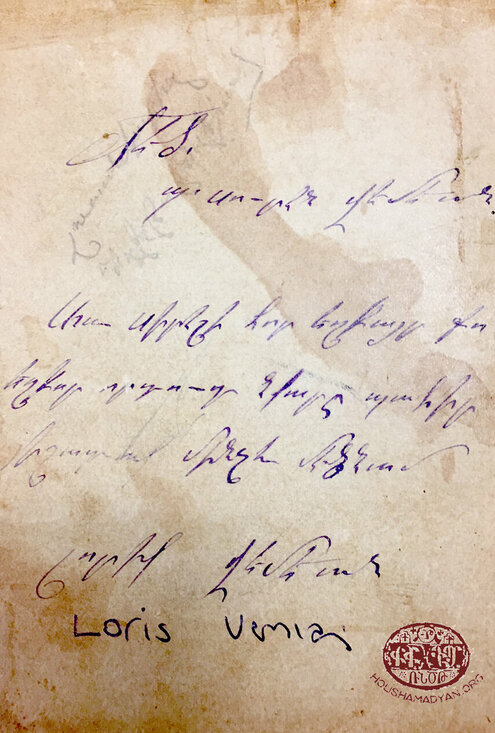

As we have already mentioned, the journal originally belonged to Eliza Donigian. However, it also contains entries written by some of her friends, presumably also orphans at the same institution. Differences in handwriting are easily detected. Making entries in the journal seems to have been customary within the orphanage, each entry being addressed to the journal’s owner. Often, entries are appended by the first and last name of the author, followed by a heartfelt note to the journal’s owner.

For example, the author of the entry titled Vorpn Ar Sokhag [The Orphan to the Nightingale] is unknown, although a postscript appended to the entry reads “December 22, 1922, Sivas – Azkanoush Iskhanian.” This postscript probably reveals the name of the author, as well as the date of the entry. However, Azkanoush Iskhanian can’t possibly be the original author of the entry’s content, as the entry also provides the date of the work’s creation as 1886. Underneath Tanial Varoujan’s poem is inscribed the following note – “Always remember your true friend. Remember the joyful and miserable days we shared. Remember, and don’t forget!” The note is signed H. Karayan, and was most probably written for Eliza by one of her friends. Underneath the poem Pnoutyan Latse [The Cry of Nature] is the note “Your friend and roommate, Vergine Koharian, forget me not” [forget me not in English in the original note]. One of Siamanto’s poems in the journal was transcribed by Melanoush Chitbashian, who also added the following notes – “A smile can cure the scars left by frowns” and “True, deep love is always silent (October 1922).”

Mariam probably began adding entries to the journal as soon as she came to have possession of it. Her handwriting can easily be discerned from the others. The majority of the entries in the latter pages of the journal seem to have been written by her. Among these entries are the inscription of Avedis Aharonian’s Oror [Lullaby] and Gamavoragan Kaylerk [The Volunteer’s Anthem], more commonly known as Harach Nahadag. Both of these works were written after the First World War, and presumably Mariam transcribed them into the journal after leaving Sivas. Aside from these transcriptions, Mariam also wrote short entries concerning her personal life. These notes were sometimes written on previously used pages with some remaining blank space. As a result, some of the journal’s pages contain material transcribed in Sivas, in addition to entries made by Mariam later in the 1920s.

She writes – “June 15, 1924 was the first day of my misery. The day when I took my first step into life, and began my many struggles. Remember that dark day after my death. On July 10, 1924, I arrived at this house, where I sometimes feel happy, sometimes miserable, and sometimes abandoned. On September 1 I heard that the orphans are in a terrible state, and cried all day. Oh God! When will you exercise your righteous judgment, and when will we have the right to call ourselves human beings?”

This entry must have been written after Mariam’s departure from the orphanage in Greece. At the time, when female orphans were released from orphanages, arrangements were made to provide them with a relatively secure future. Some girls were married immediately upon leaving, others made living arrangements with relatives, or were employed by trusted families as maids. In Mariam’s case, we presume that no living relatives were found (only later would two of her uncles, who lived in the United States, discover that she had survived the genocide). She was employed as a maid by a family. It is unclear whether the above-mentioned words were written while Mariam was still in Greece, but we do know that by December 4, 1925, she had settled down in the “English people’s home” in Egypt (presumably a trusted English family).

“A dark and terrible day (March 7, 1925, Tanta [Egypt]). I will never forget, until the day I die, the flames of love that entwined the two of us together. Alas, death has ruthlessly separated us forever.” It is unclear to whom Mariam was referring with these words. Had she just received a confirmation of her brother’s death? Or was she speaking of some other man she loved? We know that before the genocide, Mariam had entered the orphanage alongside her brother, and that the siblings were very close. He was released from the orphanage on the eve of the deportations, in order to work in his family’s fields. Thereupon, all trace of him was lost, and he was probably killed like so many others. Mariam’s family later attested that she mourned her brother’s loss until the day she died.

Eventually, Mariam’s uncles, who had settled in the United States, were able to locate her and invited her to join them. Mariam immediately began making her preparations for the trip, but her entries show that she saw it as a journey into the unknown. “The autumn of 1926 leads me into a year of loneliness . . . The Christmas table is set. But I have nobody in this foreign place who can console me. I go to surrender myself to our Maker, who has promised to be a father to us all.”

Later in the journal we find another entry, probably the last made in the journal – “April 12, 1926. I am in New York with my uncles.”

Mihran Eghigian Haroutounian

Mariam’s husband and Meline’s paternal grandfather, Mihran Eghigian, was born in Karhad, Sivas in May 1900 to Haroutioun Eghigian (the son of Eghig and Paran Eghigian) and Sharouke Terzian Eghigian (the daughter of Krikor and Karen Terzian). Haroutioun and Sharouke had at least six sons (Marouke, Arakel, Hovagim, Arshag, Mihran Eghigian and an additional son whose first name is unknown), as well as a daughter (whose name is unknown). They were all born in Karhad and likely were barley and wheat farmers. During the Genocide, all of their direct family members who hadn’t already left Kahrad were killed, except Mihran and his niece, Ovsanna Eghigian (Marouke’s daughter) both of whom survived the death march to Der Zor.

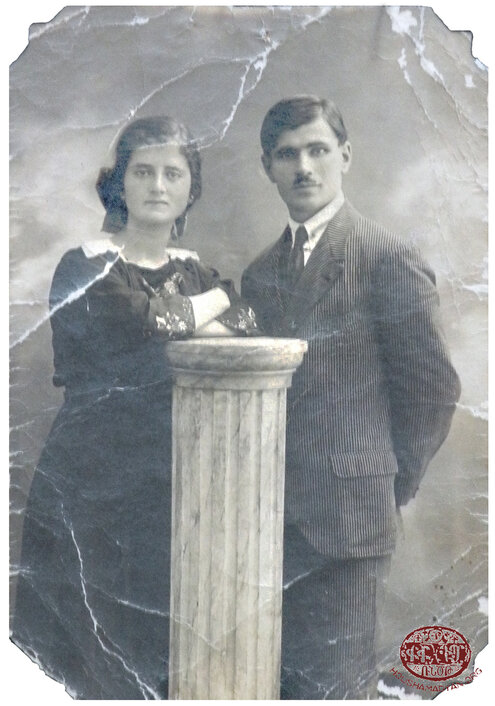

Mihran Eghigian Haroutounian had this portrait taken of himself approximately in 1919 or 1920 shortly after he arrived in Constantinople after surviving the Genocide. Upon arriving in the U.S., Mihran changed his last name to Haroutounian to honor his father, Haroutioun, who had perished in the Genocide. His sons later simplified the spelling of the family last name to Haratunian.

Ovsanna Eghigian Krikorian

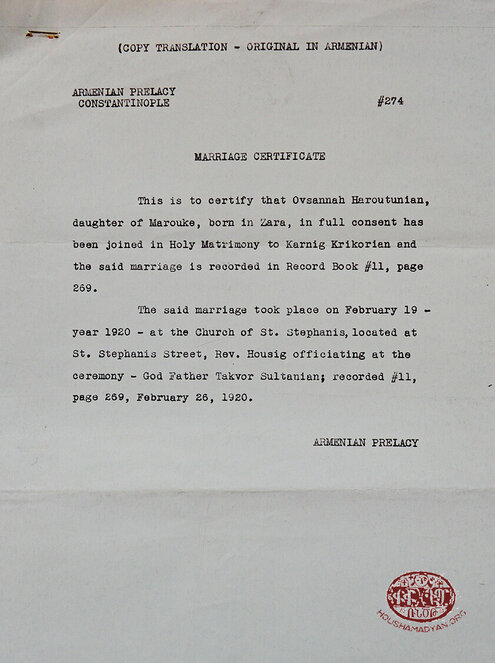

Ovsanna Eghigian was born in Karhad in 1886 to Marouke (Mihran Eghigian’s oldest brother) and Elmas Eghigian. Her parents, husband, and four children were killed in the Genocide. When Ovsanna found her way to Constantinople at the end of the war, her uncle, Mihran Eghigian Haroutounian, introduced her to Karnig Saghrian Krikorian who had helped Mihran survive the Genocide. Ovsanna and Karnig were married on February 19, 1920 in Constantinople.

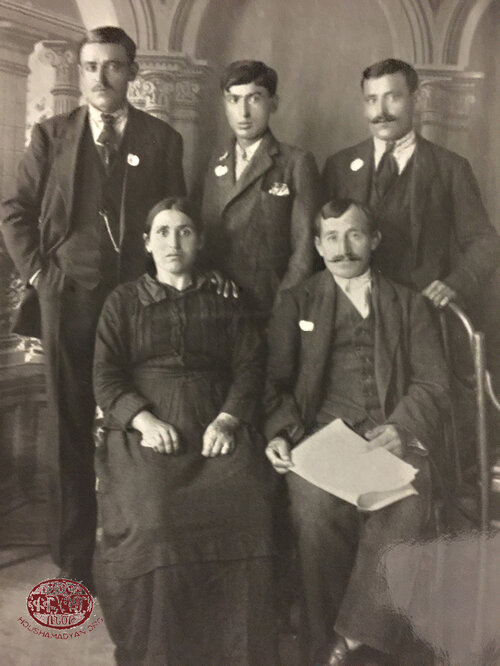

This portrait was taken in Constantinople, possibly on the occasion of Ovsanna and Karnig Krikorian’s marriage (February 19, 1920). Seated in the front row from left to right are Ovsanna Eghigian Krikorian and Karnig Krikorian. Standing in the back row from left to right are Mihran Eghigian Haroutounian, Houmiag (Hmayag?) Eghigian (Mihran’s father’s brother’s son), and Arshag Eghigian (Mihran’s older brother who had been in Constantinople before the Genocide). All were originally from Karhad and Genocide survivors. Arshag Eghigian later married Imasdouhi Soultanian (also from Karhad and the daughter of Manas “Efendi” Soultanian, Mariam Soultanian’s maternal uncle), had two daughters (Alise and Sosi), and spent the rest of his life in Constantinople. Houmiag Eghigian emigrated to Corfu, Greece and then repatriated to Armenia in the 1940s after marrying and have a son (Aram).

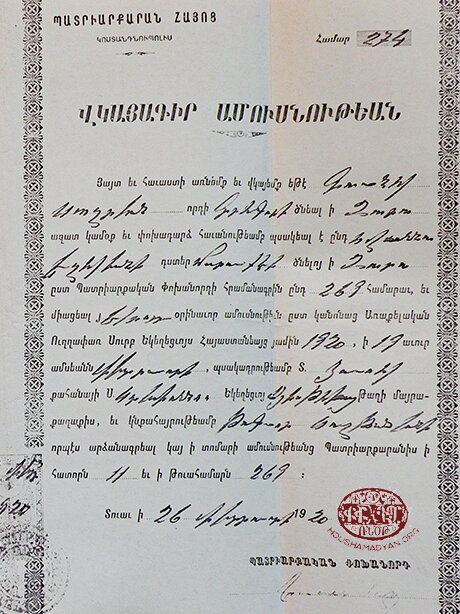

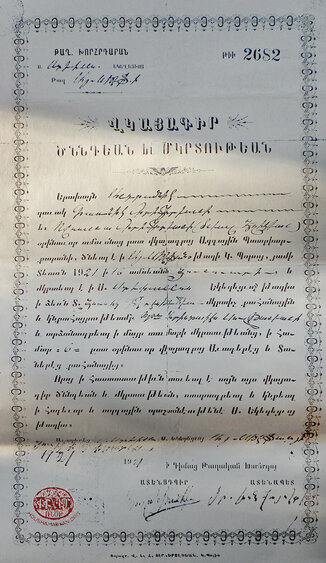

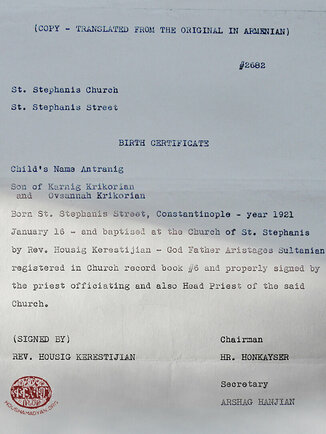

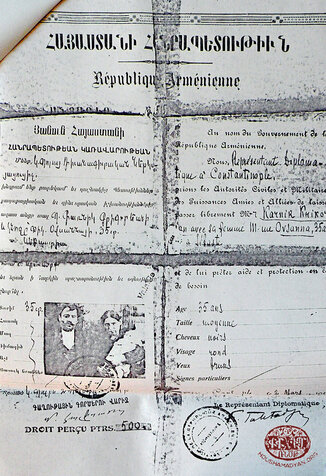

1) and 2) Ovsanna and Karnig Krikorian’s son, Antranig Krikorian, was born and baptized in Constantinople in 1921. According to this image of his birth/baptism certificate, the christening took place at the St. Stephanos Church by Rev. Housig Kerestijian with Arisdages Soultanian serving as Antranig’s godfather. Arisdages, who was also from Karhad, later emigrated to New York and married Serope Soultanian’s daughter, Zarouhi.

3) A few months after Antranig was born, the young Krikorian family left Constantinople and emigrated to New York. This is a copy of Ovsanna, Karnig, and Antranig Krikorian’s Armenian passport.

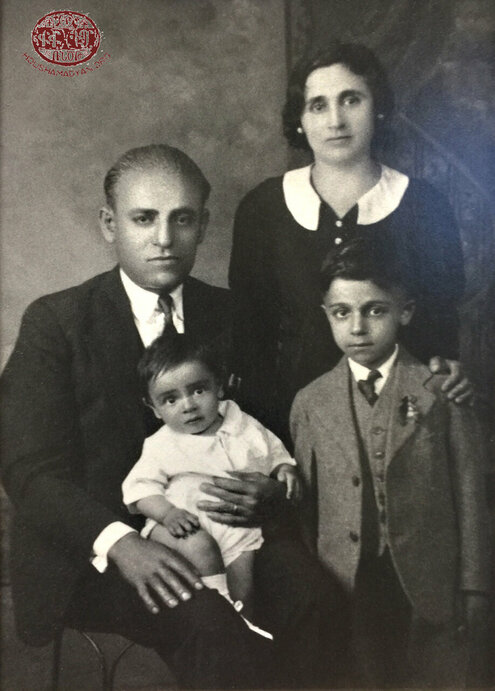

This portrait of Karnig, Ovsanna, Antranig and their daughter Shnorhig (who was born in New York in 1924) Krikorian was taken in New York around 1926.

Various Additional Karhadtsis

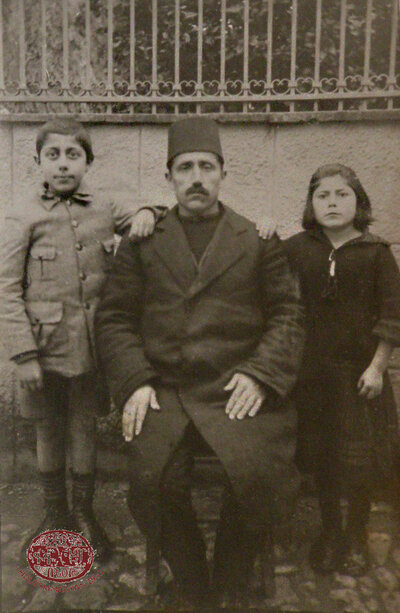

This portrait is of Takvor Soultanian, originally from Karhad, who was the godfather at Karnig and Ovsanna Krikorian’s wedding. The photograph appears to have been taken in 1905 or 1910, but it is unknown where it was taken or the names of the children with him. Takvor was a Genocide survivor who moved to Constantinople and lived there until his death.

Arakel Eghigian (Mihran Eghigian Haroutounian’s older brother) emigrated to Bulgaria before the Genocide and had five children. Arakel sent this portrait, taken in Bulgaria in 1921, to Mihran; it is of Arakel’s oldest two children, Lucineghan and Artin (Haroutioun) Eghigian. Mihran and Arakel never met each other because Arakel had left Karhad for Bulgaria before Mihran was born in 1900. After Arakel died after World War II, his widow and likely all five of their children repatriated to Armenia.

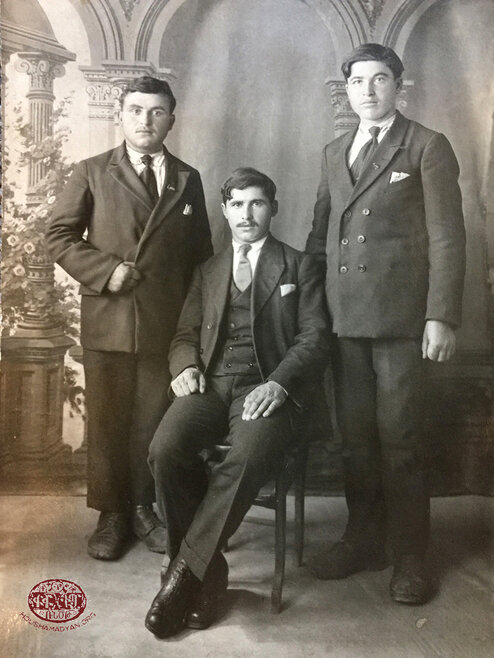

1) In this portrait, standing left to right, are Kalousd Yalian and Haig Aram Eretsian, both of whom were from Karhad, survived the deportation, went to Constantinople after the war, and then emigrated to New York. The identity of the seated man is unknown but it could be Karnig Antraeasian-Sagaerents, also from Karhad, who survived the deportation to Der Zor with Kalousd and Haig Aram. It likely was taken in Constantinople in 1920.

2) This portrait was taken of several of the men from Karhad living in New York in approximately 1927. Standing from left to right are Kalousd Yalian, Varaztad Soultanian (Serovpe Soultanian’s son and Mariam Eghigian Haroutounian’s cousin), Arisdages Soultanian (the godfather at Antranig Krikorian’s baptism who married Serovpe Soultanian’s daughter, Zarouhi), and Hovanness Antreasian (a distant cousin of Karnig Saghrian Krikorian who helped Mihran emigrate to the U.S.; Hovanness also wrote a brief (eight pages) history of Karhad that describes village life as well as the 1915 deportations and village survivors). Seated from left to right are Haig Aram Eretsian, Israel Terzian (another distant cousin of Karnig Saghrian Krikorian who likely had emigrated to New York before the Genocide), and Mihran Eghigian Haroutounian.

This October 1926 wedding photo is of Smpad Yalian and his wife (name unknown); it is unclear where it was taken. Smpad was born in Karhad, survived the Genocide and was re-united with fellow Karhad survivors in Zara, Sivas after the Armistice of 1918. He was Kaloust Yalian’s brother.

Bardizag (Province of Izmit)

Evdoxia Knnabjian Vemian

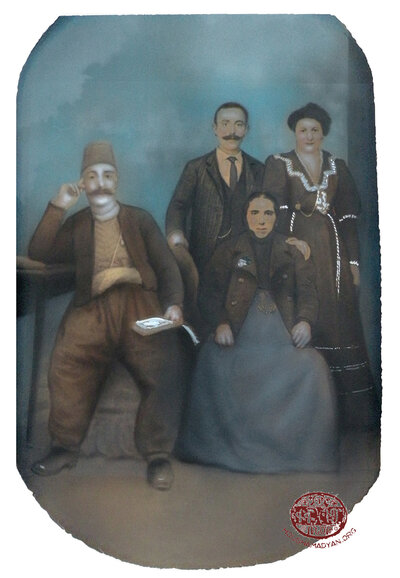

Meline’s maternal great-great grandparents were Mgrdich Alachanian and Baidzar Mikhailian Alachanian, who had at least seven children. Their oldest daughter was Zarouhi who was born in 1865. Zarouhi married Mikail Knnabjian (who was born in 1863) and they had at least seven children, including Evdoxia Knnabjian Vemian who was Meline’s maternal grandmother. They were all born in Bardizag. In this portrait seated left to right are Mgrditch Alachanian and Baidzar Mikhailian Alachanian and standing left to right are Mikhail Knnabjian and Zarouhi Alachanian Knnabjian. It likely was taken in Bardizag or possibly in Constantinople, about 1910. Mgrditch had died before this portrait was made and his image, which was taken several years earlier, was inserted later to complete the family portrait.

1) This is a portrait of Baidzar Mikhailian Alachanian likely taken around 1915 in Bardizag or Constantinople.

2) Garabed Alachanian was Evdoxia’s first cousin and was born in Bardizag in 1900. This photograph of Garabed and Evdoxia was taken in Constantinople in August 1919. The inscription on the back, which was written by Evdoxia, states that it was taken a month and a half after her return from “exile,” her euphemistic reference to the four years she was forcibly separated from her family during the Genocide and over 50 members of her extended family from Bardizag were killed.

Evdoxia Knnabjian’s Surviving Siblings

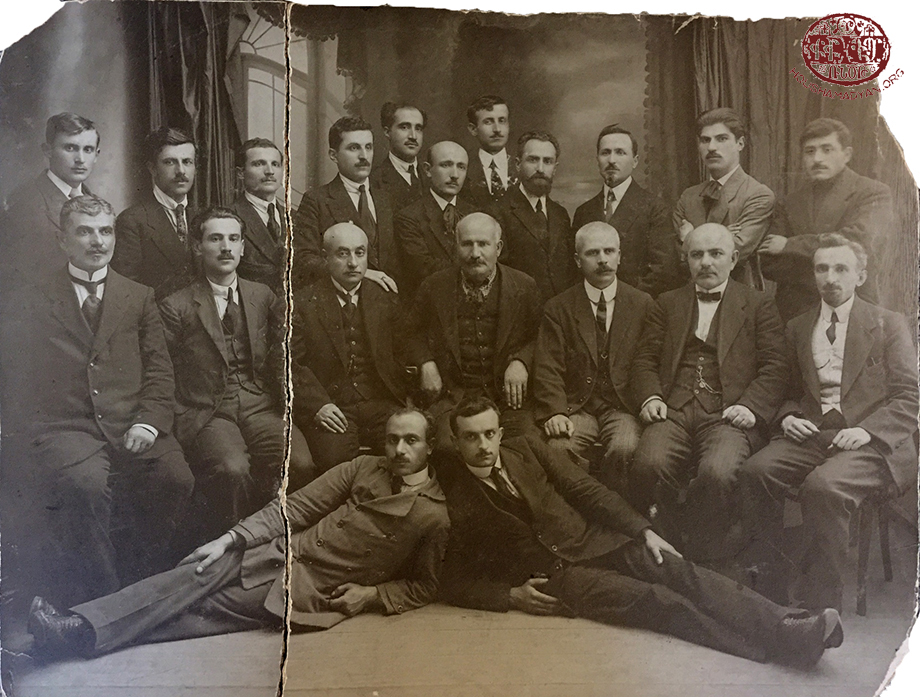

Garabed Knnabjian, Evdoxia and Stephan’s only other sibling who survived the Genocide, was born in Bardizag in 1892 and eventually made his way to Bulgaria. This group portrait was taken in 1919, apparently in Sofia, Bulgaria. The wreath ribbon appears to read “To ARF incomparable activist Arzouman from the Balkan comrades.” The caption in the back of the photograph states that it was “Dikran Khachiguian’s memorial event.” Arzouman is the nom de guerre of Dikran Khachiguian. On the top row, the third man from the far left is holding a journal in his hand that appears to be the ARF journal “Djagadamard.” Stepan or Garabed Knnabjian appears to be seated in the first row, the second man from the far right.

Like his sister, Evdoxia, Stepan Knnabjian eventually left Constantinople for Cuba. This is a photograph of a group of Armenian men in Havana, Cuba who worked together in 1924. Stepan is the fifth man standing from the left; the identities of the other men, and the type of work they performed, are unknown.

Additional Alachanians

Ardem Alachanian Paraghamian (Zarouhi Alachanian Knnabjian’s younger sister) was born in 1880. She married Nishan Paraghamian (who was born in 1871); Nishan and his brothers were master carpenters in Bardizag. Ardem and Nishan had three children: Shakeh Paraghamian Anoushian (born in 1896), Torkom Paraghamian (born in 1900), and Vehanoush Paraghamian Ellaguzian (born in 1909). Shakeh married Levon Anoushian and they had two children, Alis and Garbis Anoushian. They were all born in Bardizag. This portrait was taken in Constantinople in 1917. Ardem Alachanian Paraghamian is seated in the center. Standing in the back from left to right are her two daughters, Vehanoush Paraghamian Ellaguzian and Shakeh Paraghamian Anoushian. In the front row from left to right are Garbis (the baby seated on Ardem’s lap) and Alis Anoushian (standing next to Ardem), Shakeh’s children. The family escaped Bardizag for Constantinople immediately before the Genocide with Ardem, Shakeh, and Vehanoush cloaked the black veils so they wouldn’t be recognized.

1) This portrait was taken in Rumeli Hisari (an area in Constantinople by the sea where Ardem’s family was then living) in 1925. It is of all the same individuals (positioned in their identical locations) as the previous photograph but this time including Nishan Paraghamian (Ardem’s husband seated next to Ardem in the center of the photograph) who possibly recently had been reunited his family.

2) This photograph is of Megerdich Alachanian, a son of Zarouhi Alachanian Knnabjian’s brother, Abraham Alachanian. It likely was taken in 1905 or 1910 in Bardizag or Constantinople.

This photograph was taken (and sent to Evdoxia) in 1931 and likely taken in Constantinople. Seated in the front from left to right are Abraham Alachanian and his wife, Yeghsabet Hairabedian Alachanian. Standing in the back from left to right are Torkom Paraghamian (Ardem Paraghamian’s son) and Megerdich Alachanian (Abraham and Yeghsabet’s oldest son); everyone in the photograph had been born in Bardizag.

Erzurum/Garin

Souren Vemian

Meline’s maternal grandfather, Souren Vemian, was born in Erzurum (likely in the Chay Ghara quarter) in May 1890 to Kevork and Dirouhi Azarian Vemian. Kevork Vemian was born in 1865 and both he and Dirouhi were born in Erzurum.

The Vemians of Erzurum were known throughout the Ottoman Empire as being one of the top armament makers and master gunsmiths who supplied weapons for the sultans and the imperial court. [9]

This group portrait is of an Armenian Revolutionary Federation meeting in Sofia, Bulgaria in 1918; Souren Vemian is reclining in the front row on the left (the identities of the remaining men are unknown).

After Souren emigrated to the U.S., he was active in the New York Garin Compatriot Union, serving on their executive committee in 1949.

Loris Vemian

Souren Vemian’s brother, Haig, married Verkin Ahungoian and they had at least one child, Loris Vemian, who was born in Erzurum in September 1914.

- [1] Ethel Daniels Hubbard, Lone Sentiles in the Near East: War Stories of American Women in Turkey and Serbia, 1920, pp. 53-57.

- [2] Id. p. 57; Jay Winter (ed.), America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 236; Gordon Severance and Diana Severance, Against the Gates of Hell: The Life & Times of Henry Perry, University Press of America, 2003, p. 345; Auroraprize.com/en/stories/detail/regular/8793/mary-louise-graffam.

- [3] America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915, p. 239.

- [4] R.H. Kevorkian, Le Génocide des Armeniens, Paris, 2006, p. 543.

- [5] Lone Sentinels in the Near East, pp. 59-60.

- [6] Id., p. 62.

- [7] Ararat: Searchlight on Armenia by the Armenian United Association, vol. 5, University of Michigan Library, 2010, p. 151.

- [8] Id. at p. 239, n. 77.

- [9] Ugur Umit Ungor and Mehmet Polatel, Confiscation and Destruction: The Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011, p. 18; Anahit Astoyan, Armenians in the Ottoman Economy, Part 2, October 26, 2009 (http://hetq.am/eng/print/31213/)