Ashekian/Iynedjian/Bakalian/Bohdjelian Part II

Author: Anny Bakalian, New York, 21/01/2020 (Last modified 21/01/2020)

Post I: The Descendants of Parsegh Ashekian from Kayseri/Gesaria who settled in Lebanon

POST I introduces the seven Ashekian siblings of Garabed Parsegh Ashekian from Kayseri/Gesaria: Parsegh, Harutiun, Dikran, Nazaret, Misak, Mihran, and their sister Nevrig, the only sister. Then the focus is on the fourth and fifth generations who settled in Lebanon circa 1920.

Parsegh Uzun (tall for Turkish) Ashekian (the First Generation) settled in Kayseri/Gesaria because of the persecution of the Persians in the late 1700. He had two sons, Bedros and Garabed (the Second Generation).

(1) Bedros (born in Kayseri/Gesaria circa 1810—died Kayseri/Gesaria circa 1890s) had three children from his first wife—Parsegh, Mariam, and Yeghisapet; and he had eight offspring from the second wife.

(2) Garabed (born in Kayseri/Gesaria in 1818—died Adana in 1903) married Hripsimé (née Murad Tekeyan) Garabed Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria circa in 1825—died in Adana in 1904) and had six sons and the seventh child was a daughter. Garabed and Hripsimé settled in Adana (circa 1888) because their children lived there.

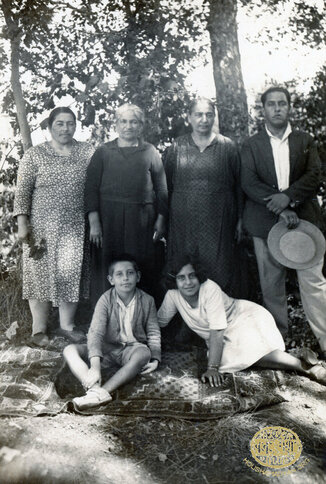

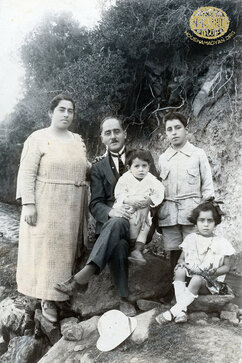

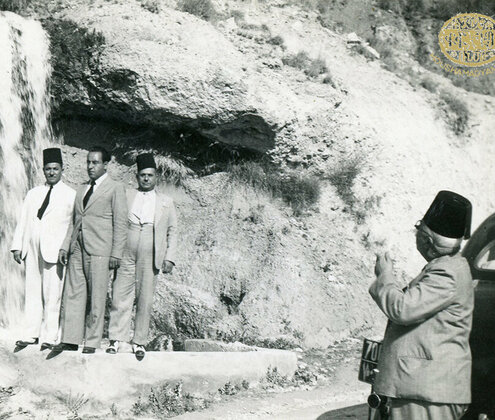

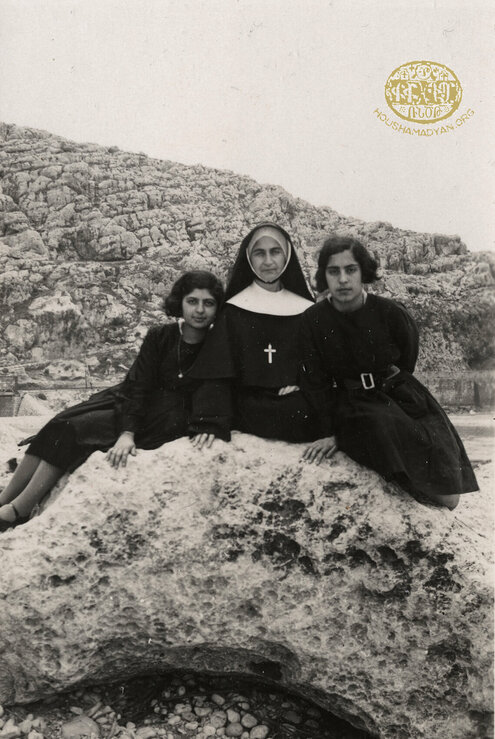

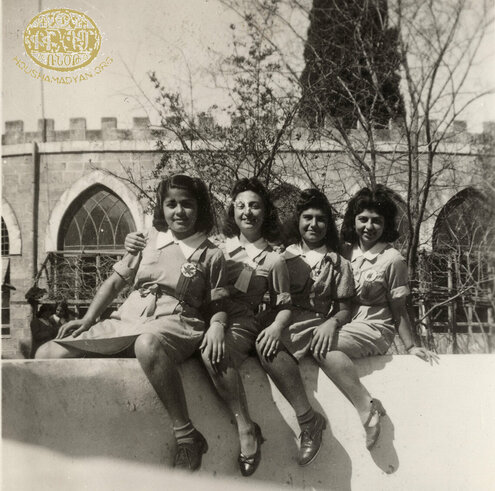

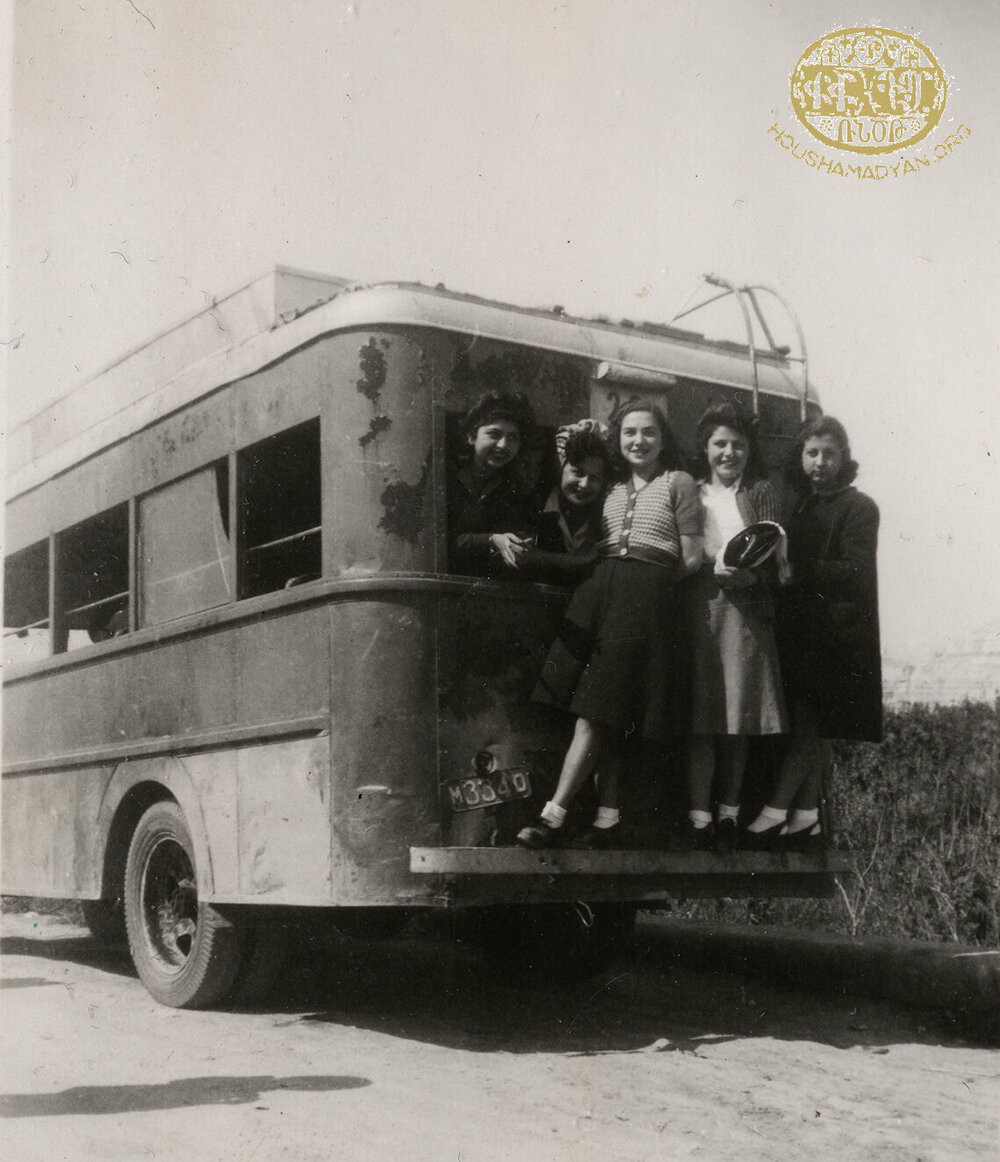

The women and children in this photo are the descendants of three brothers Parsegh, Dikran and Mihran Ashekians of Kayseri/Gesaria. They are maybe in a café at Fawwar Antelias River (north of Beirut), where there are oleander flowers on the trees. From left to right: Louise Mihran Ashekian, Victor (née Mihran Ashekian) Levofet Pambukdjian, Marina (née Parsegh Ashekian) Bedros Ashekian, Arpine (née Diran Kazandjian) Apkar Salatian, Tsoline (née Dikran Ashekian) Garabed Djirdjirian, Anahid (née Diran Kazandjian) Arsen Bedrossian, Lousadzine Dikran Ashekian; Sitting are: Zarouhi Dikran Ashekian, Haiguhi (née Parsegh Ashekian) Sarkis Bakalian; the children: Vasken Sarkis Bakalian, Berdj Diran Kazandjian, Chaké (née Bedros Ashekian) Puzant Najarian, Mampile (née Sarkis Bakalian) Hagop Touryantz, Sirarpie (née Bedros Ashekian) Kevork Yaghdjian, and Mayda Levofet M. Pambukdjian.

Garabed operated caravans to Iraq and Iran with his brother Bedros. While the decades passed, he ignored his sons’ concerns for his safety and health and continued to do business well into his old age, not wanting to burden his sons financially. His brother’s grandson, Hovhannes Iynedjian of Kastemoni/Kastamonu, would often have Garabed import precious mesh, ropes, and other items for him to sell to shopkeepers. In the autumn, after the grape harvest ended, farmers would sell their horses and donkeys for low prices, and then, they would buy them back in the spring. Taking advantage of this reality, he would go to the bazaar, buy the animals at affordable prices, tattoo the letter “G” (for Garabed) on the legs and ears of the animals, send them to the farm of Tutlu Budjak, and then bring them back for sale in the spring.

Garabed’s wife, Hripsimé (née Murad Tekeyan) Ashekian was a strong woman, born in Kayseri. Her father, Hadji Murad Tekeyan had escaped Persian persecution, first going to Cappadocia and later settling in Talas. His name, Tekeyan, is related to Teke, which in Turkish means buck (male goat). Hripsimé’s mother’s name was Pepron. Hripsimé had seven brothers (Kerovpé, Kalusd, Simon, Garabed, Harutiun, Krikor, Kevork) and a sister Srpuhi. The renowned poet Vahan Tekeyan was the son of Kalusd and Kerovpé’s son Diran Tekeyan was on board one of the five Allied ships, possibly as an officer, as they rescued the Armenians of Musa Dagh (Musa Ler) from July 21 through September 12, 1915. At this time there were six Armenian villages in Musa Dagh that mounted an armed resistance to Ottoman deportation orders during the genocide. Instead of being marched to the desert, they climbed 1,355 meters to the top of the mountain, where they hung large banners and sent swimmers to flag allied ships. In total, 4,000 men, women, and children embarked from Musa Dagh on these ships and took refuge in in Port Said, Egypt.

Hripsimé lived well into her old age with her children and grandchildren. She was weary and suffering from rheumatism, stayed in her bed under the supervision of Assyrian and Greek women in Adana. She had witnessed her sons’ death; Nazaret died young in 1886, Parsegh passed away in 1901 and Misak, the doctor, expired in 1903. When her husband died, she followed him shortly after and she was buried next to her husband in Adana.

The Third Generation

The first brother: Parsegh Garabed Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria on May 11, 1848—died in Adana on April 25, 1901) was the first of the siblings to move from Kayseri/Gesaria to Adana. It was the largest city in the region, sitting on the Seyhan (Sarus) River in the heart of Cilicia. The rich soil made this region a productive for agriculture, cotton, sesame, oats, and citrus fruit. It was also rich in industry. The Turks called this region Chukurova/Çukurova. The port of Mersine is close to Adana, facilitating exporting and importing goods to Europe and cities along the Mediterranean. Parsegh must have been ambitious and resourceful. He established several businesses and guided his brothers and kin.

This is what Garabed Ashekian, son of Parsegh, tells in his book:

Circa 1885, the Ashekian family faced financial problems, so Parsegh left his hometown, Kayseri/Gesaria, and headed to the commercial city of Adana, which was the seat of the governor of Cilicia and had progressive agriculture. He arrived in Adana in seven days, accompanied by muleteers. While investigating the business situation of Adana, he started to trade on foot. Afterwards, he established grocery stores, first in Adjem Khan, under the watchtower, and then he rented a shop next to the gate of Yeni Khan. His youngest brother, Mihran, came to help him because his business had picked up and he had purchased few properties by Yeni Khan.

Later, he corresponded with Mihran Tekeyan of Marseille, who was the son of his maternal uncle, and they began to import and export goods. When his brother, Nazaret, came to Adana from Kayseri, he sponsored him; he became an accountant of the state treasurer in Tarsus/Darson.

When the state taxed businessmen like Parsegh, supposedly because the state’s treasury was in deficit, Parsegh Ashekian contacted his brother, Dikran. He came from Kayseri to Adana, and then he went to Tarsus/Darson [...]. Dikran investigated the matter and confirmed that his brother had already paid all his taxes, so he saved him from conviction.

Consequently, Parsegh suggested to his brother to move to Adana to be the attorney for all his dealings, especially his contracts, commercial, properties and other assets and also his relations with state. Dikran accepted the invitation and relocated with his family to Adana. The eldest brother, Parsegh Uzun Ashekian, changed his business name to “Uzun Ashekian Brothers.”

About this time, Sarkis Bakalian, Dikran’s young brother-in-law, arrived from Kayseri to Adana and began to work in the grocery store, subsequently the business expanded due to these men’s efforts [Dikran and Sarkis]. Then, upon the suggestion of their physician brother, Misak, they removed “Uzun” from their surname. They then made Bakalian a partner, renaming their enterprise: Ashekian-Bakalian […]

What differentiates our family? There were many families with the last name Ashekian in Ottoman Empire’s provinces, even one of the Armenian patriarchs of Constantinople was an Ashekian, and there was also a statue of an Ashekian in the Armenian Quarter in Jerusalem. Garabed, the chronicler, seems he liked to keep the Uzun. The Patriarch of this Clan migrated from “Greater Armenia” to Kayseri and called him Uzun Ashekian because he had long legs in Turkish. Also aşık is a Turkish word for knucklebone.

Parsegh’s physician brother, Misak, sent him a letter suggesting he purchase a farm, as a way to stay busy. Despite that Parsegh was exhausted [due to old age] and he already had prosperous and growing business, he still inspected the Ekinji farm that was bordering the village Abdi Oghlu, and bought it. He also purchased a big black Cypriot donkey and he began to visit the farm everyday. Very pleased and charmed by the surrounding vast lands, he purchased a second farm known as Tutlu Bujak by the River Djeyhan/Ceyhan, at the bottom of Mount Dede. [1]

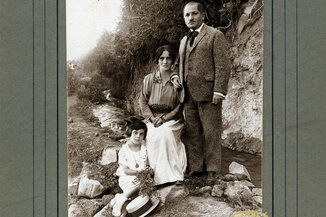

ParseghGarabed Ashekian and Diruhi (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Parsegh Garabed Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria, circa 1864—died in Beirut, June 11, 1968) were married circa 1886 in Kayseri; she was about 18 years old and he was 38 years old. They were cousins, Diruhi was the daughter of Mariam who was the daughter of Bedros Parsegh Ashekian and her father was Harutiun Iynedjian [she was the second daughter of four girls, and later had three brothers].

Parsegh and Diruhi had five children. The first daughter (Haiguhi) died in her infancy, then they had:

- Garabed Ashekian (born in Adana 1889—died in California in 1983) [see POST III]

- Haiguhi (née Ashekian) Bakalian (born in Adana, March 24, 1892—died in Beit Mery, Lebanon in 1966)

- Marina (née Ashekian) Ashekian (born in Adana 1896—died in Beirut in 1974)

- Hagop Ashekian (born in Adana in 1901—died in Encino (CA) in 1989) [see POST III]

Their son Garabed, in his book describes the Ashekian household, with four sons (of six) living under the same roof with their parents, at the turn of the 20th Century: Our house was located on the edge of Kazandjilar Street in Adana. On the West was the Armenian Adana diocese and its courtyard. On the North was the Holy Mother of God Armenian Church, with its high bell tower. This church was built because Governor Bahri Pasha of Adana, a Kurd, supported this project as well as Primate, Archbishop Mushegh Seropian. On the South of our house was Divan Yolu; it was a wide avenue that begins with Ters Kapi and ends with the Seyhan River and the Taşköprü (Stone Bridge), constructed in the Fourth Century BC. […] The sons of Hadji Garabed Uzun Ashekian, Parsegh, Dikran, and Mihran lived in one big household. [There were ten girls and three boys] and grew under the watch of their grandmother [Hripsime (née Murad Tekeyan) Ashekian] and grandfather [Garabed Parsegh Ashekian]. All these people lived a patriarchal life until the Massacres of Adana in 1909. [2]

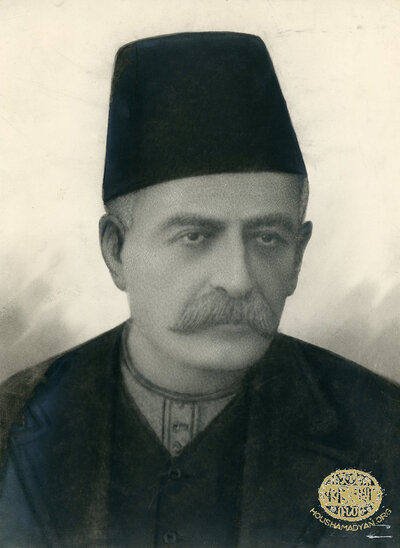

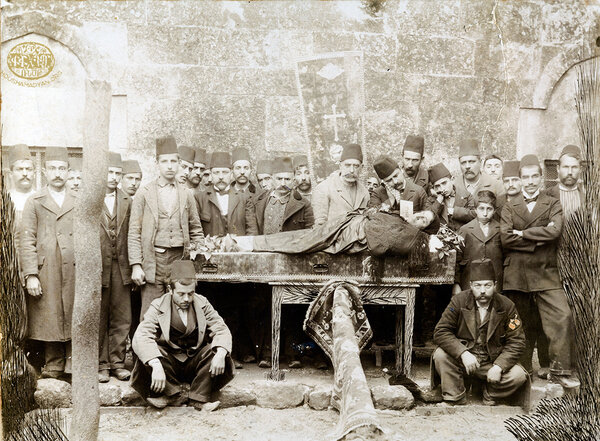

This photo was in the collection of Haiguhi (née Parsegh Ashekian) Bakalian. While she and her Ashekian generation were born in Adana yet they identified with Kayseri/Gesaria. A young woman has died in Adana possibly in childbirth, her young husband is wearing a fez and in his hand with a handkerchief and looking at her face, and next to him are his sons, one about 14 years old and the other 9 years old. Armenian women did not attend funerals at that time in Adana and maybe other places. Photograph: Yerem Nercesian.

Parsegh Ashekian suffered from “red blood cells” (a type of anemia). His physician brother, Dr. Misak Ashekian and other physicians could not heal him. He died in Adana on April 25, 1901.

Diruhi was 33 years old when she became a widow. She was pregnant with her last son, Hagop, when her husband Parsegh died.

Diruhi was quite a traveler and more importantly, by luck she survived dangerous conditions during her long life, avoiding the massacres, deportations, wars and authoritarian regimes that plagued so many of her contemporaries. Before her husband Parsegh Ashekian died in 1901, they initiated a trip for few months to visit her sisters, Gyuldudu and Nervig in Banderma/Bandırma, and they hoped that the hot springs of Bursa would cure him. In 1904, she took her father Harutiun Iynedjian and her four children for a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

In 1905-06, she went with her father and four children to see her two brothers Hovhannes and Nazaret Iynedjian in Kastamoni/Kastamonu. The ship that sailed from Mersine was to drop them in Samsun on the Black Sea; however, the trip was arduous because the Armenian Revolutionary Federation had attempted to assassinate Sultan Abdul Hamid II (the Yildiz/Yıldız assassination attempt, 21 July 1905). When they arrived in Constantinople, Diruhi sent a message to her youngest sibling Bedros Iynedjian to get the aid of the relative who converted to Islam as a youth and became the police commissioner of Beshiktash/Beşiktaş district (Constantinople). Boghos (Kyamil) Ashekian [3] resolved the issue first by obtaining permission to get the travelers off the boat, and then he bought train tickets from Haydar Pasha (Constantinople) to Ankara. Finally, Diruhi, her four children and her father traveled by cart to Kastamonu. Before returning back home to Mersin by land, the travelers visited her siblings Dikranuhi (née Iynedjian) Torosian and Bedros Iynedjian and met his fiancé Pérouze Hampartsum Suzmeyan.

In 1909, Diruhi avoided the Adana Massacres because she was in Egypt with her son Garabed visiting relatives. During the Genocide, Ashekian-Bakalian family members were exempt from military service and deportation because their flourmill was serving the military. After the Franco-Turkish War (May 1920-October 1921), the Armenians were evacuated; she went with her sons Garabed and Hagop to Cyprus and then Constantinople in 1920.

After the Smyrna fire in 1922, Garabed Ashekian decided to leave the Ottoman Empire. He left Constantinople with his wife, mother and brother Hagop; a ship took them to Constanța (Romania) in a night.

When her daughter, Haiguhi (née Ashekian) Bakalian became a widow, she went to Romania in 1938 to visit her mother Diruhi, brothers, and other relatives. Haiguhi traveled with her daughter Mampile (age 19), son Vasken (age 17) and her niece Chaké (age 17). When they returned to Beirut, Diruhi was with them; again she escaped World War II and the Soviets.

Diruhi’s last 30 years were in Beirut. She lived in Pakrat Bakalian’s household, which included her daughter Haiguhi, and grandson, along with his wife and three children. She was fortunate to see her sons, Garabed and Hagop, and their families who were passing through Beirut before they settled in North America.

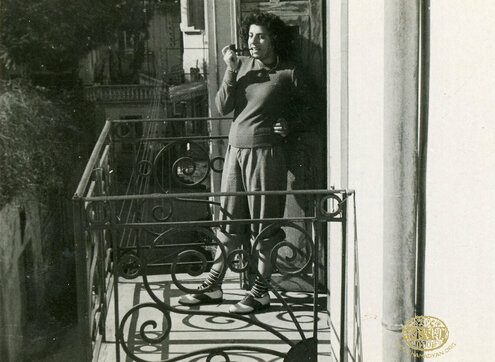

She spoke only Turkish, was illiterate, and smoked into her 90s. Every morning and evening, Diruhi did her prayers in rote in Armenian. She kept the Easter Lent until her death, abstaining from meat, fish and animal fat for 40 days. Diruhi (née Iynedjian) Ashekian’s “LOKUMLOU” recipe was adopted in Romania (Turkish Delight Cookies) and it was published in Anahid Doniguian’s Armenian cookbook in Lebanon.

Diruhi’s date of birth was not known; therefore when she died in Beirut in 1968, two years after her daughter Haiguhi’s, the age of her death was estimated at 104.

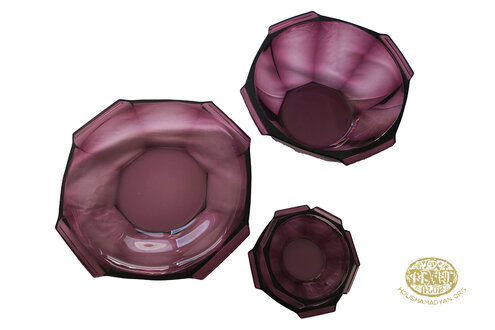

Diruhi (née Iynedjian Ashekian) bought this ashtray in Cairo in 1909 while visiting relatives; she and her son Garabed Ashekian were lucky that they did not witness the Adana Massacre.

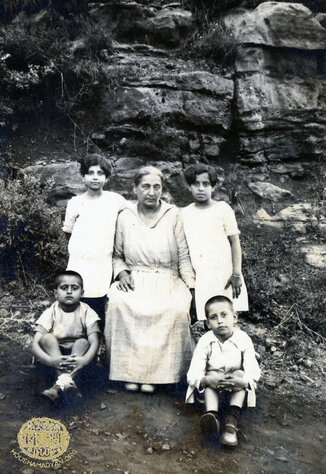

1. Diruhi’s last photo 1963 with her great grandchildren, Lena, Ruby, Tania Bakalian, Beirut. They called her: Nene. Diruhi died in Beirut in 1968

2. Diruhi (née Iynedjian) Ashekian’s Lokoumlou (Turkish Delight Cookies). Ingredients for shell: 100 gm crème fraîche or sour cream, 1/2 cup butter, melted and cooled, 1/2 tablespoon sugar, pinch of salt, vanilla, about 2 cups all-purpose flour.

Ingredients for the filling: 100 gm plain Turkish Delight/Lokum, and powder sugar. This recipe makes about 24 Lokumlou pieces. Preparation: 1) Line baking sheets with parchment paper; 2) Mix the cream, butter, sugar, salt and vanilla in a large bowl; 3) Add the flour, a little at a time; 4) Work into a soft, but not sticky dough; leave to rest for 30 minutes; 6) Prepare the Lokum (comes in 4 x 4 cm): Cut in half, sprinkle with powder sugar, and rollout between fingers, about 5 cm; 7) Divide the dough into 6 small buns. Rollout each into a small circle about 12 cm in diameter. Cut into 4 equal wedges. Start the wider side of Lokum and roll to narrow end into a crescent; 8) Preheat the oven at 350 Fahrenheit/177 Celsius; cook until barely colored; 9) Sprinkle powder sugar.

The second brother:Harutiun Garabed Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria in 1851—died in Cyprus circa 1920) dealt with ready-made clothes for some time in Constantinople; then he came to Adana to be close to his parents. He was a businessman as well as a city contractor and tithe collector and similar occupations. He also engaged with his brothers in transactions.

Harutiun married Annug (née Giragos Demirjian) Harutiun Ashekian; her father was from Hadjin (now Saimbeyli). They had three sons and two daughters:

- Nazaret Harutiun Ashekian, a boy, died young

- PeruseHarutiun Ashekian, a girl, died young

- Hetum Harutiun Ashekian (a son, after his mandatory military service he became ill and died in Adana)

- Vahan Harutiun Ashekian (born Adana, circa 1890–died possibly in Egypt)

- Verjin Harutiun Ashekian (born in Adana, circa 1892—died in Cyprus, circa 1960s)

Vahan went to Cyprus during the massacres of Adana and moved from there to Egypt, where he found a job in a steamboat company and traveled back and forth from Egypt to the Persian Gulf. Harutiun and his family were not deported because he was employed at the Ashekian-Bakalian flour factory in Adana. During the evacuation of Cilicia in 1920-1921, he went to Cyprus with his family. His wife Annug died in Cyprus in the early 1960s. Their daughter Verjin was not married; she lived in Nicosia until she died.

The third brother: Dikran Garabed Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria on February 4, 1855—died in Adana in 1920) was educated in Kayseri/Gesaria, he became a lawyer and his clients were in the Kayseri’s government circles.

Dikran married Marie (née Hovsep Bakalian) Dikran Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria circa 1869—died in Beirut circa 1940s) in circa 1885 in Adana.

Then his elder brother Parsegh invited him to move to Adana to help him with government matters. His brother-in-law, Sarkis Bakalian followed suit, settling in Adana and founding the Ashekian’s grocery business. Both Dikran and Sarkis were smart, ambitious, hardworking and successful. Ashekian-Bakalian became their business name.

Dikran and Marie had four daughters and one son; the first two children were born in Kayseri/Gesaria, the others in Adana circa 1890:

- Adele (née Ashekian) Kazandjian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria circa 1886—died in Baghdad in the early 1960s)

- Murad Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria circa 1887—died in Beirut, circa in 1958)

- Lousadzine Ashekian (born in Adana circa 1892—died in Beirut on October 1, 1968)

- Zarouhi Ashekian (born in Adana, circa 1897—died in Beirut in 1963)

- Tsoline (née Ashekian) Garabed Djerdjirian (born in Adana in 1901—died in Marseille in the 1960s)

It is interesting that their mother, Marie (née Bakalian) Ashekian, gave birth in 1901 while her first child Adele got married in 1901. Only the eldest, Adele and youngest, Tsoline, were married.

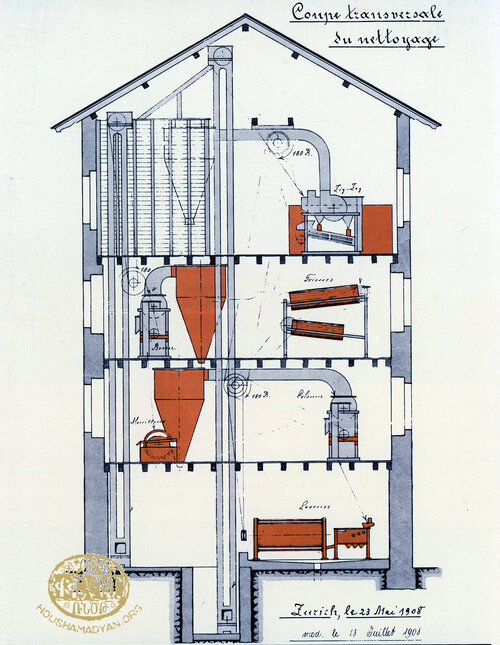

A document from the Ottoman archives in Istanbul indicates that the Ashekians operated factories in Adana required fuel as early as 1901. Furthermore, Dikran Ashekian received a dispensation from paying taxes on fuel for ten years. Here is the translation:

Dikran Ashekian, citizen of the Ottoman Empire (teba-yı devlet-i aliyyeden) who established the flour factory in the Sofubahçesi/Sofubahchesi district of Adana province, requested exemption from customs taxes of gazojin [sic] used for machines and other instruments necessary for the factory. The pertinent register form has been sent along (with the request). It was discovered that the factory was granted the license for [kargan ve zai] on 29 Kanunevvel 1323 (11 January 1908) and the regulation regarding the exemption of customs tariff from the instruments and tools in such cases was passed in [19 April 1316] and with the confirmation of the His Excellency this regulation was renewed for another ten years. This decision was taken after the scientific committee of the Ministry and the confirmation of the Council of State and Deputy Great Assembly inspected the instruments. All examinations passed in the Ashekian factory, thus a confirmation was granted; therefore, the information regarding the exemption from the customs tariff should be sent to the (relevant office).

Signature: Minister of Commerce and Public Works

29 Mart 1324 fi 10 Rebiülevvel 1326 (12 April 1908). Brackets refer to indecipherable text in the original Ottoman. [4]

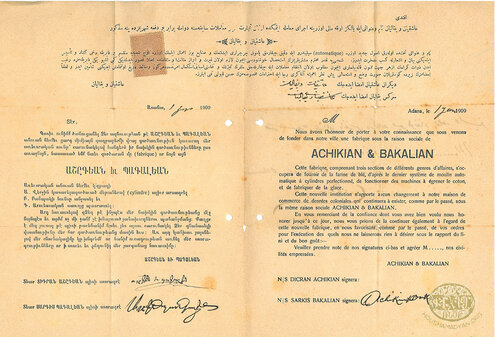

This document is a promissory note (sanad in Turkish/Arabic) dated 1 January 1909, Dikran Ashekian and Sarkis Bakalian introduces their new firm "Ashekian & Bakalian" and they trust that the Ottoman Bank will continue their business.

On January 1, 1909, Dikran became a partner with his brother-in-law, Sarkis Bakalian in a new firm, Ashekian & Bakalian. A promissory note (sanad in Turkish) in Armenian, Turkish and French, addresses the director of the Ottoman Imperial Bank in Mersine and assures the bank that Messrs. Dikran Ashekian and Sarkis Bakalian will maintain their business as before and hope that the bank will trust them as previously. This document guaranteed that the Ashekian & Bakalian company will invest in a factory with three mechanized sections: a flourmill—equipped with the latest automatic engines to produce fine wheat flour, a cotton gin and an ice machine. Bakalian paid for half of the equipment and the factory would be on Ashekian land in Adana.

In April 1909, during the Adana Massacre thousands of Armenians were killed and the Armenian quarter looted and destroyed.

Garabed Ashekian writes in his book:

My paternal uncle [Dikran] was imprisoned, under the pretext that he had fired at and killed Turks from the upper floor of his [old] factory during the massacres of Adana. The Ashekian-Bakalian wholesale grocery store was plundered. Sarkis Bakalian took refuge in Cyprus. The Turks also robbed all the goods of the Ashekian-Bakalian factory, burned their houses and stores. Their farms remained without owners, because nobody remained in the city.

Dikran Boghajian of Tokat, who was the clerk of the grocery store, was instructed by my paternal uncle to take ownership by proxy of their entire business, included the farms, since the harvest season was close.

The governor of Adana was replaced after the massacres. When the new governor assumed his duties, he wanted to see Dikran Ashekian. He was told that Dikran had been imprisoned. Immediately he reviewed the file, understood that the charges were a fabrication, and released him from prison. [5]

While the Ashekians and Bakalians sustained substantial material damages to their businesses, homes, and possessions, they survived with their ambitions. In 1908 Dikran and Sarkis had ordered machines from Davero, Henrici, & Co. millbuilders in Zurich. [6] Their electric flourmill was one of four modern factories in Adana, and the only Armenian-owned one at that time.

The History of Armenians in Adana [in Armenian], edited by Puzant Yeghiayan, confirms in Chapter 7: In pre-WWI period, there were four flour factories in Adana, Ashekian-Bakalian being the only Armenian one. Further, there were four ice factories including Ashekian-Bakalian and another Armenian owned firm, Pambukdjian-Donigian. Ashekian-Bakalian, Pambukdjian-Mardigian, and two other Armenian firms operated the four industrial cotton gins. [7]

More importantly, the factory would spare their and most of their relatives’ lives during the Genocide. However, Dikran Ashekian’s family as well as their son-in-law Diran Kazandjian and grandchildren were deported in 1915, supposedly a decision that would save their lives. The Committee of Union of Progress (CUP), especially the “Three Pashas”–Talaat Pasha, Enver Pasha and Djemal Pasha—exercised absolute power on the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1918. Dikran had been an active member of the Governing Council and the Chamber of Commerce. During the Adana Massacre in 1909, Dikran befriended Ahmed Djemal Pasha. By 1915, Djemal was the commander of the Ottoman Fourth Army, whose field of operations was Bilad al-Sham (Syria). Dikran beseeched his friend to allow them to stay in Aleppo, eventually staying there until the end of the war.

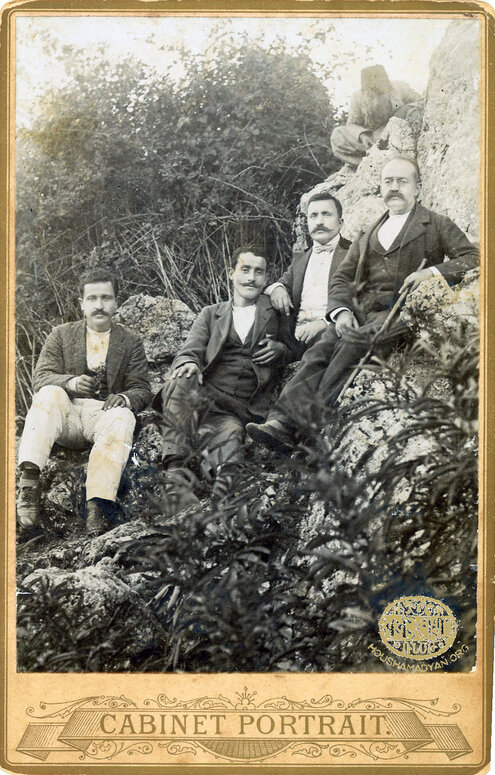

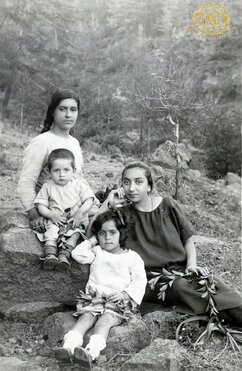

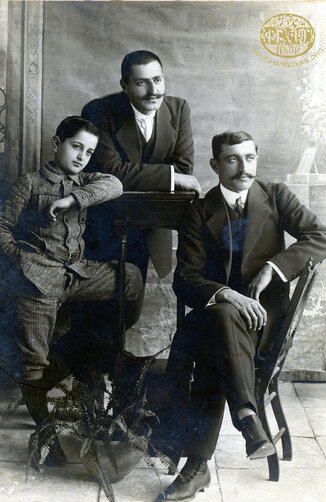

Murad, Lousadzine, Zarouhi and Tsoline. On their left/behind are the family of their son-in-law, Diran Kazandjian. In Diran’s lap is Anahid, next is Adele (née Ashekian) Kazandjian and their oldest daughter, Arpine. The boy with a fez is Haroutune Kazandjian on the left of his grandfather.

During the Armistice (1918), Dikran Ashekian’s family returned to Adana where their father died of pulmonary disease in 1920. He was an enthusiast of Armenian affairs and served his people on the provincial, civic, and parish councils. He was also involved in governmental affairs and served as a member to the Governing Council, the municipality, and the Chamber of Commerce.

The rest of Dikran Ashekian’s family moved to Cyprus circa 1920. Ultimately, they settled in Lebanon.

The fourth brother: Nazaret Garabed Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria in 1857—died in Tarsus/Darson in 1886) was a good economist and scientist. He was appointed accountant to Tarsus/Darson’s governmental treasury with connections with his brother Parsegh. Nazaret threw a banquet in the garden of the Alawites of Tarsus/Darson and they served wine. He caught a cold that developed into pneumonia. He died at 29 years of age and was buried in the Armenian cemetery of Tarsus/Darson.

The fifth brother: Misak Garabed Ashekian (Doctor) (born in Kayseri/Gesaria in 1860—died in Adana December 1, 1902) graduated from the Imperial University (now Istanbul University) (Darülfünûn-u Sultanî) in 1884 as a doctor of medicine. He did his residency in Bitlis. The locals were very grateful for his service during the epidemic of 1887-1888. Next, Dr. Misak Ashekian practiced in Mush. There, the local government jailed him because he was allegedly a revolutionary. His friends Kuyumdjians of Bitlis started to send him food through Dr’a Kibab, a Syrian Maronite dressmaker. Eventually, Misak married Dr’a when he was released.

Misak wanted to be close to his parents and brothers, so he moved to Adana and practiced internal medicine. He developed diabetes and one of his legs was amputated. He went to Paris and obtained an artificial leg. He died at the age of 42 years old.

The sixth brother: Mihran Garabed Ashekian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria in 1862—died in Adana in 1907) was the second Ashekian to help his eldest brother Parsegh in Adana. First he managed the Ashekian inn and worked with Sarkis Bakalian in his grocery business. He decided to change to large-scale import/export. He partnered with Kevork Kalbadjian of Hadjin to found the “Ashekian-Kalbadjian” corporation.

Mihran married Gyulena (née Garabed Pambukdjian) Mihran Ashekian (born in Adana in 1896—died in Zahle (Lebanon) in 1964); her family was from Kayseri/Gesaria. Their first child was a boy who died as baby. Later, they had four daughters:

- Eliz (née Ashekian) Levofet M. Pambukdjian (born in Adana circa 1899—died Lebanon circa 1930s)

- Louise Ashekian (born in Adana in 1901—died in Beirut)

- Victoria/called Victor (née Ashekian) Levofet M. Pambukdjian (born in Adana circa 1904—died not known)

- Paruhi (née Ashekian) Sarkis Ourfalian (born in Adana in 1906—died in Beirut). She was born just before her father’s death; he was disappointed she was not a son.

Mihran took his family on holiday to Everek (now Develi), a town near Kayseri. Hearing that one of the rich Ashekians was coming, the Kayseri Parish Council members of the Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church tricked their visitor to pay their military tax because they were overdue. While this duty was on all Armenians, the committee petitioned the Kayseri government to catch Mihran. So the police brought Mihran to Kayseri and charged him the duties allocated of the church. The Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church is in the southern quarter Kayseri/Gesaria erected in 1856 because the Armenians live there. This Church is still one of the few Armenian churches outside Istanbul where they still have occasional services.

Mihran was irritated and disgusted by the mercilessness and callous behavior of the Kayseri Parish Council. Then Mihran Ashekian spent that night in the house of his cousin, Yeghisapet (née Bedros Ashekian) Movses Yeghia Taslakdjia. In the morning, when he woke up, he had lost his voice.

Upon his return to Adana, Mihran was diagnosed with throat cancer. He was in great pain, becoming addicted to morphine injections. He went to Constantinople, Vienna and Paris to find a cure. The French doctors advised him to go back home. He returned to Adana where he died. After his death, his brother Dikran took care of the firm “Ashekian-Kalbadjian.” Like all the Ashekians, Mihran’s family moved first to Cyprus and eventually settled in Beirut.

The sister: Nevrig (née Garabed Uzun Ashekian) Telalian(born in Kayseri/Gesaria on May 17, 1870—died in Beirut circa 1939) married Djivan Telalian of Kayseri/Gesaria, who was a commission agent in Mersine. Nevrig’s brothers asked them to move to Adana; they gave Djivan seed money to establish a wholesale hardware store. He established a successful business in the heart of Adana’s goldsmiths’ market. Unfortunately, Djivan fell ill with an infliction leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. Nevrig took care of her husband for long years, but she would say, “This is my fate.”

After the Adana massacres in 1909, Djivan and Nevrig moved to Mersine like her siblings. Djivan died during World War I. During the Cilician Evacuation, she went to Cyprus and then she settled in Beirut.

Parsegh, the patriarch of the Ashekians, was called Uzun (tall in Turkish) for his height. Some of his descendants were also tall such as Nevrig. One day she was leaving the Hamam (bath) in Adana with a relative, a passerby said: “Look at this tall woman.” Nevrig heard this and looked around, searching for this tall woman. Her companion told her, “They are talking about you!”

Diruhi and her other sisters-in-law, as well as her nieces and nephews affectionately called her “emé,” sister in Turkish.

In 1931, Nevrig took a ship from Beirut to Marseille and back to chaperone her niece Tsoline, Dikran’s daughter, who was getting married.

When Haiguhi Bakalian’s husband died, her aunt, Nevrig lived with her until her own death. She was buried in the Armenian Orthodox Cemetery off Damascus Street (near Hotel de Dieu), established in 1924. She was a social woman, who, like her niece Haiguhi enjoyed the mountains in Lebanon.

She was attentive and friendly towards the children of her brothers and their grandchildren.

The Fourth Generation in Lebanon

Descendants of Parsegh and Diruhi Ashekian

Garabed Parsegh Ashekian (born in Adana on October 13, 1889—died in Southern California in 1983).

Hagop Parsegh Ashekian (born in Adana, on April 25, 1901—died in Encino (CA) in 1989)

Haiguhi (née Parsegh Ashekian) Sarkis Bakalian (born in Adana, March 24, 1892—died in Beit Mery, Lebanon, on July 15, 1966) attended an Armenian school in Adana.

She lived in a large complex, adjacent to the Holy Mother of God Armenian Church and its high bell tower in Adana. In one part of this building was her family—father Parsegh, mother Diruhi, sister Marina and brothers Garabed and Hagop. Her uncles, Dikran and Mihran, and their families, as well as her grandfather, Parsegh, and grandmother, Hripsime, lived in different sections of the house. On April 14, 1909, a mob of locals attacked the Armenian quarter killing, vandalizing, and looting; the Ashekians escaped.

Haigouhi and her sister Marina witnessed the Adana Massacre in April 1909, when they were 17 and 13 years old respectively. In the early 1960s, before her death, Haiguhi revealed to her grandchildren that she and her sister walked over cadavers, and when Marina lost her slippers, she marched barefoot. They were marching with fellow Armenians, clapping and shouting: "Padişahım çok yaşa" (Long life to the Sultan). They also remembered that they were hiding behind the machines of the manual (old) mill of their family, and fighting off rats and vermin.

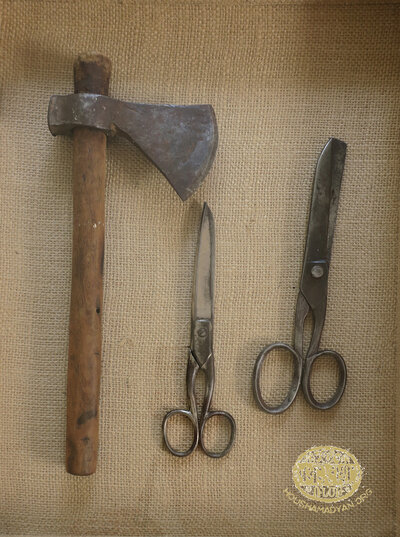

When the Ashekians returned to their home, they found that it was looted. Only one object was found because it was hanging behind the kitchen door; it was an ax that the family used to break bones when cooking. Haiguhi traveled with this ax from Adana, to Mersin, Larnaca and Beirut. Decades later, her granddaughter took the ax and Haiguhi’s scissors to the U.S.A. and put them in a memory frame.

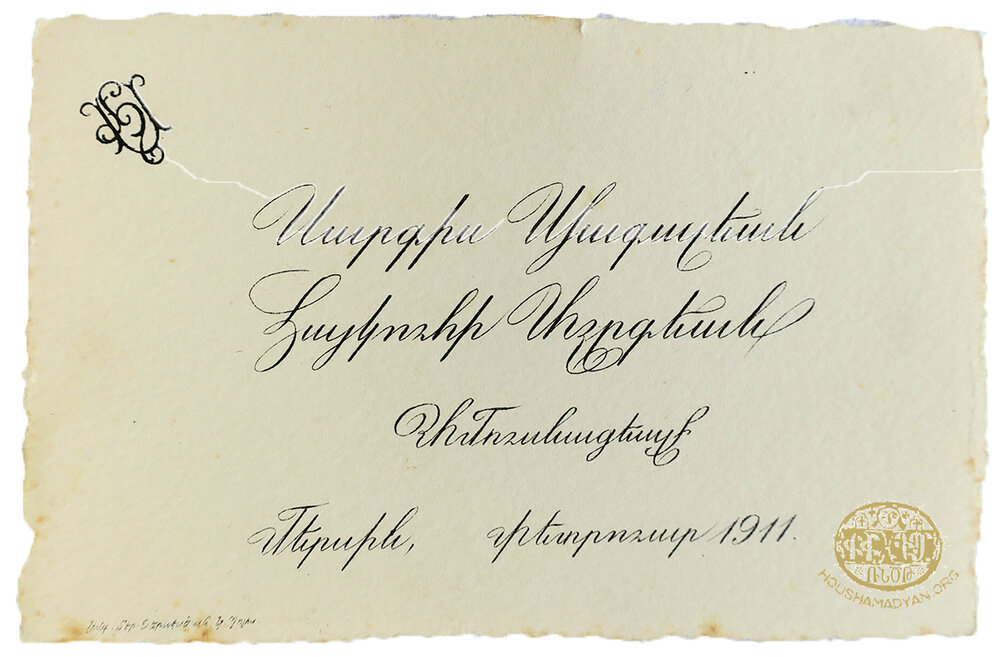

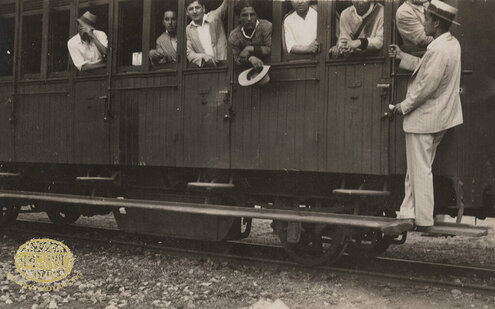

After the massacre, the elders rented a house in Mersine because it was calmer and sheltered for the children and women. Still their businesses and properties remained in Adana. Thus, the men commuted during the weekdays and returned to their homes on Sundays and holidays. While there was a double track rail line from Adana to Mersine [67 km-41 miles] for passengers and freights (built in 1886), it seems that the men preferred to travel by steamboats, maybe because they enjoyed the breezes of the Mediterranean. Their transit Adana-Mersine was about 2½ hours each way. Haiguhi married Sarkis Bakalian on February 20, 1911 in Mersine. The bride was 19 years old, the groom 34 years old. Haiguhi’s trousseau included the clothes, household linen, and other belongings that were bought from the famous department store Orosdi-Back in Adana.

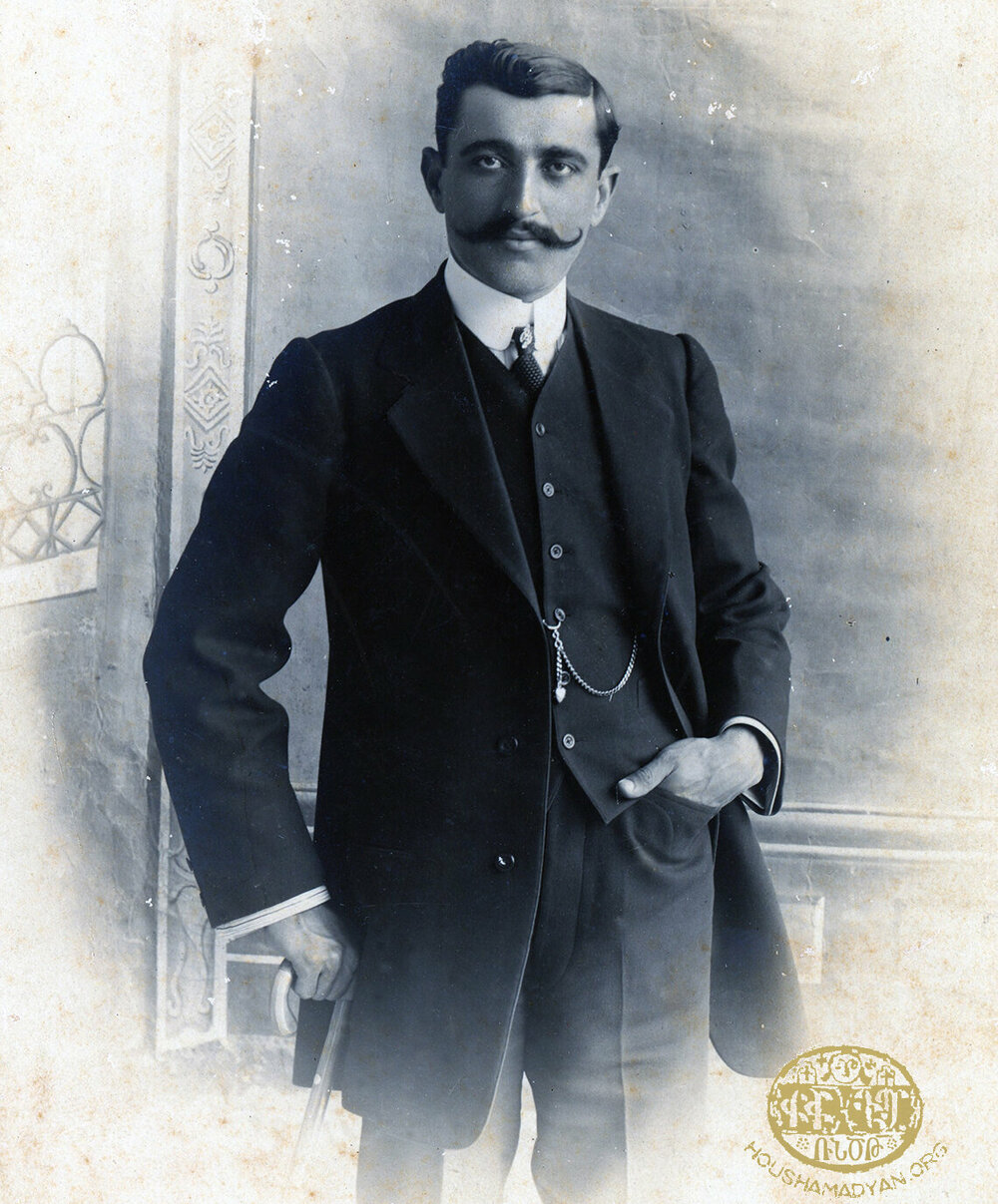

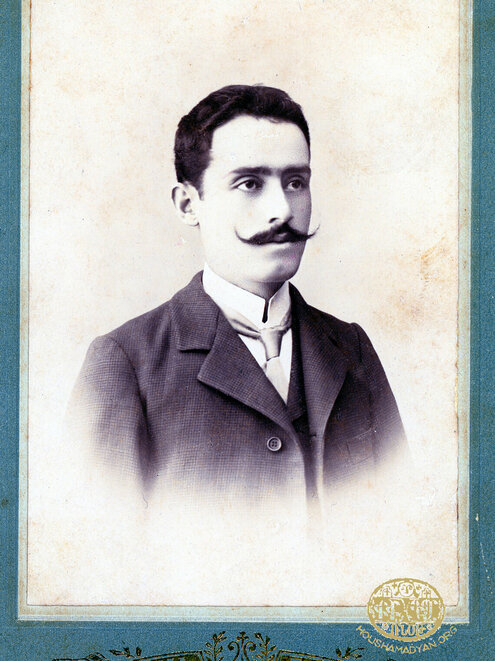

Sarkis Bakalian (born in Kayseri/Gesaria, in 1877—died in Beirut on July 31, 1937) spend his childhood in Kayseri, but his father Hovsep was absent most of his son’s life, partly because he joined the Ottoman Army (maybe during the Russo-Turkish War-1877-1878); his mother Firkanda must have raised her son. Sarkis was intelligent, hardworking and serious man, but had little education; he spoke Turkish, as did many Armenians of Kayseri in the 19th century. As an ambitious young man, Sarkis relocated to Adana because business opportunities were better than in Kayseri and his sister Marie (née Bakalian) Dikran Ashekian lived there.

First Sarkis Bakalian worked for his brother-in-law Dikran Ashekian, then he became his partner in a wholesale grocery business. Puzant Yeghiayan confirms in his book, that the “Ashekian-Bakalian family played important role in the grocer imports.” [8]

Not content, Sarkis wanted more challenging enterprises. In 1908, Dikran Ashekian and Sarkis Bakalian ordered automatic machines from Davero, Henrici, & Co. millbuilders in Zurich. Sarkis paid for half of the equipment of the mill. On 1 January 1909, Dikran and Sarkis received a promissory note from the Ottoman Imperial Bank in Mersine acknowledging the new firm of Ashekian & Bakalian.

The Adana Massacre took place in April 1909, the Turks murdered many Armenians and destroyed their churches, industries, workshops, shops, houses, and properties throughout Adana Vilayet (province)/Cilicia. The Ashekian-Bakalian wholesale grocery commerce was plundered and burned and their stores and houses were raided and robbed. Sarkis Bakalian took refuge in Cyprus. He returned when there was a new governor, Ahmed Djemal Pasha, who had been sent by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) government to restore the Armenians’ confidence, and his business resumed.

The new Swiss-made flourmill, with automatic engines, arrived in Adana. It was one of four modern milling factories in Adana, and the only Armenian-owned one at that time. According to the Ashekian book, Sarkis become indispensable to the success of the Ashekian-Bakalian firm. It is at this time that the two Kayseri families, Ashekians and Bakalians, strengthened their business ties with marital alliances in 1911.

The home of Sarkis and Haiguhi Bakalian was in Mersine. There, Haiguhi delivered five babies, but only three survived into adulthood—a boy and a girl, and the last boy was born in Cyprus:

- Pakrat Sarkis Bakalian (born in Mersine on December 24, 1913—died Baabdat, Lebanon, on April 25, 1976 during the Civil War)

- Mampile (née Bakalian) Touryantz (born in Mersine on May 5, 1919—died in Queens, NY, in 2000)

- Vasken Sarkis Bakalian (born Larnaca, Cyprus in November 8, 1921—died in Beirut in March 25, 2007)

The Ottoman Empire, supported by Germany, entered World War I by raiding Russia on the Black Sea in October 1914. Eventually, the Ottoman Empire Army commanded the Ashekian Bakalian flourmill in Adana. An Ottoman officer supervised the operations at the factory while Sarkis Bakalian and the miller were procuring flour for bread for the troops. Garabed Ashekian writes in his book, “During the Great War, those associated with the Ashekian factory were exempt from military service and deportation because the factory served the military authorities.” [9] A laissez-passer confirms that Sarkis Bakalian was manufacturing flour for the Ottoman army through the years of the genocide:

Bab-ı Ali (The Office of the Grand Vezir), Ministry of Interior Affairs. Encrypted Telegram (Office). Factory owner in Tarsus, from the Armenian community, Shalvardjian Mardiros Efendi is under contract to supply the military with one million kilogram flour; Hornan, a member of the Mersine Assembly of Administration, to deliver meat, barley and oat; Sarrafian Dikran and Seragan from Tarsus to produce beans and chickpea; and Bakalian Sarkis from Adana to provide bulgur and flour. To avoid shortages in provisioning the military, above mentioned contractors along with Krikor Magaroghlu, the son of Vanesi, the chief secretary of the railways construction company, will have authorization to travel within the province as well as in the neighboring provinces and towns. Consequently, they are granted permission by the military and possess documents in hand to travel freely within the province as well as in the neighboring provinces and towns. [10]

Another document from the Ottoman archives in Istanbul mentions that Sarkis Bakalian was selected to Adana Province Administrative Assembly. [11] The Deputy Governor of Adana wrote to the Ministry of Interior Affairs informing them that a Greek (Ligor Yadis) and an Armenian (Sarkis Bakalian) were appointed to the Assembly to replace two Muslims (Mustafa and Esad Efendi). Dated on February 9, 1919, this manuscript has the seal of the French “Services Administratifs, l’Administrateur en Chef” and in handwriting: “Vu et autorisé / le 9.2.18 P. l’administration en Chef et p.o. Le Secrétaire Général,” and ends with a signature (not legible).

It was fortuitous that Ashekian & Bakalian invested in a flourmill, for it safeguarded their lives and those of their relatives during the 1915 Genocide and deportations. Sarkis Bakalian was a Freemason and it is assumed that he called favors for his relatives and he helped other Armenians during the war and the Genocide.

Sarkis Bakalian had the foresight to befriend the Ottoman high officer who was overseeing the operations of the flourmill. This man was a gambler. As Sarkis was not a devotee of playing cards himself, he engaged a young Greek named Bodossaki [12] to play with the officer and let him win. Additionally, the officer depended on Sarkis to supply him cash. Once he asked Sarkis a bigger amount than before; Sarkis showed him the keys of the factory saying, “Why don’t you manage the business yourself.” After few minutes of reconsideration, he told Sarkis, carry on. In 1919, the Turkish high officer tipped off Sarkis to leave from Adana immediately, he said, “Go now and you can return later.” [13]

In a rush, the Bakalians and few relatives took a ship from Mersine to Cyprus, bringing with them the wealth that they could carry and sentimental objects.

Sarkis Bakalian’s family relocation to Cyprus was different from most Armenians who left Cilicia after World War I. After World War I, tens of thousands Armenians who had been deported in 1915 were repatriated to their homes in Cilicia; they joined those who had remained in their homes.

Sarkis and Haiguhi settled in Larnaca, Cyprus; it was also where their last child, Vasken, was born.

Quickly, Sarkis realized that Cyprus had few opportunities in business. He took a reconnoiter voyage; he embarked a ship in Larnaca and visited Beirut, Alexandria and Marseille. He chose Lebanon because he found the culture familiar and Turkish was spoken in the marketplace.

Lebanon was under French Mandate from 1920 to 1943. Starting from 1920, Sarkis Bakalian was making commercial contacts in Beirut and he often visited his family in Larnaca. Then, he stayed in Beirut for a year to become a Lebanese citizen and during that period he partnered with Mohammed Abdelkader Tawil to operate a flourmill in Debbas Square in downtown Beirut. Since 1924, Sarkis was in Beirut permanently; but his family joined him a little later.

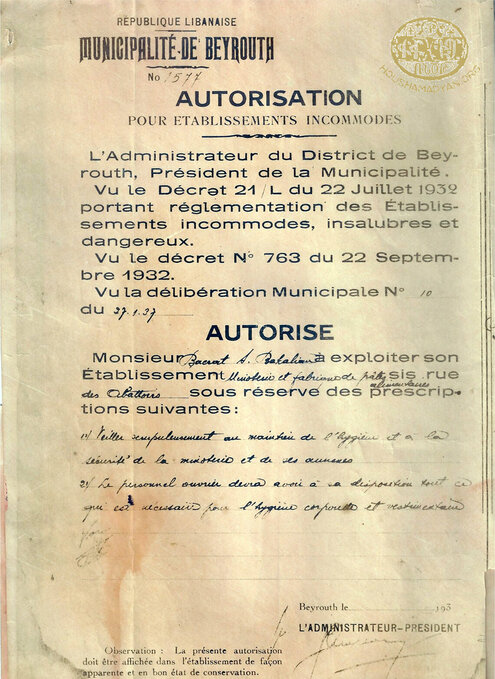

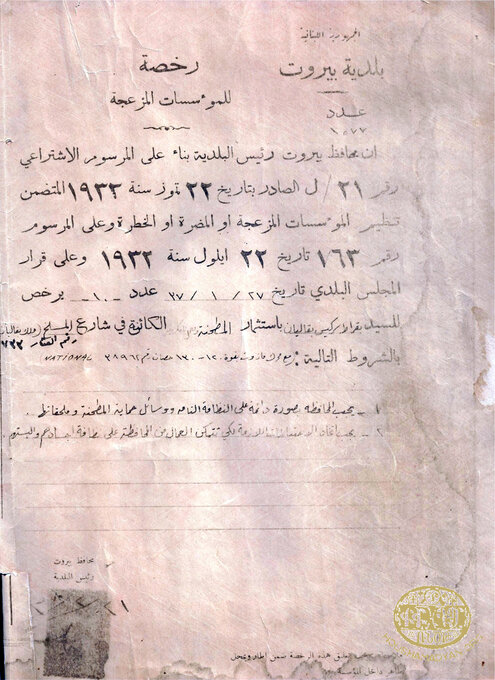

Next Sarkis Bakalian bought property adjacent to the city’s slaughterhouse on Brazil Street, Karantina, and on September 22, 1932, the Municipality of Beirut granted his elder son Pakrat the rights to establish a flourmill and pasta factory there. He imported machines (with a capacity of 25,000 kilos/24 hours) from MIAG-Germany.

The flourmill, Grands Moulins du Liban—Sarkis Bakalian, was functional by the end of 1936. A journalist touring the new factory with the German technician in July 1937 reported in the Armenian daily Aztag that 200 bags of flour were produced per day, wheat was brought by train from Horan (Syria) and previously from Hama, Homs, even Aleppo and announced that macaroni will be produced in the fall. [14]

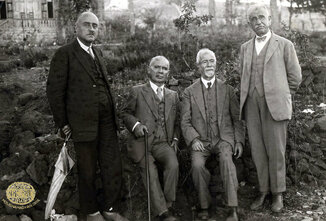

1.1920 c. Sarkis Bakalian (seated in the center) and his Peers possibly in Cyprus

2.Larnaca, 1920: Mr. and Mrs. Bedirian and their eldest daughter Angele. [The photo studio used the same background scenery as the one of Sarkis Bakalian and family in Larnaca 1924]. The Bedirian couple may have met Sarkis and Haiguhi Bakalian in Cyprus or could be from Adana. While the Bakalians settled in Lebanon, the Bedirian lived in Egypt. They had four children: Angele, Joseph Antoine, and Alice. They were Armenian Catholics. They came in the summer with their children to Dhour el Choueir, Lebanon in the 1930s. They became friends and they correspond in Turkish or Armeno-Turkish.

3.Mediterranean in Alexandria in 1928: Mrs. Bedirian and for children, Angele, Joseph Antoine, and Alice, swimming.

Sarkis Bakalian was a philanthropist without pretentiousness, boasting, or arrogance. Bishop Grigoris Balakian (1875-1934) devoted two lengthy paragraphs, in Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918, about Sarkis Bakalian’s altruism:

[M]y most fervent protector was the noble Sarkis Bakalian, a prudent, taciturn, and humble Kayseri native who secretly took care of many helpless Armenian families. When he heard that a defenseless Armenian woman and her children were hungry, he would immediately give her a measure of flour. Many neighboring Armenian families, whose unspeakable wretchedness I witnessed, appealed to his kindness, and he provided flour to them. [15]

Furthermore, Balakian reports his experiences:

One time in the spring of 1918 when the homes of Armenians were being searched and those in hiding were arrested, exiled, and killed, Kurkjian inquired about my perilous situation. He then requested moral support for me from Sarkis Bakalian. This other self-sacrificing and generous friend sent to me through Kurkjian that I was not to fear if I were arrested; he was already to give a bribe of thousand gold pounds to secure my release.

As a factory owner and supplier of flour to the Ottoman army, Bakalian had great influence with the governor-general and genuine friends among the other Turkish high officials. Kurkjian went to see Sarkis Bakalian, and he brought me hundred Turkish pounds for my journey to Switzerland. Dr. Vartabadian also contributed a hundred gold pounds, and with two hundred gold pounds at my disposal, I already considered my plan a success. Then Bakalian invited the central stationmaster of the Adana railroad to my hiding place, and all the necessary arrangements were made for me to reach Kara Punar by rail. [16]

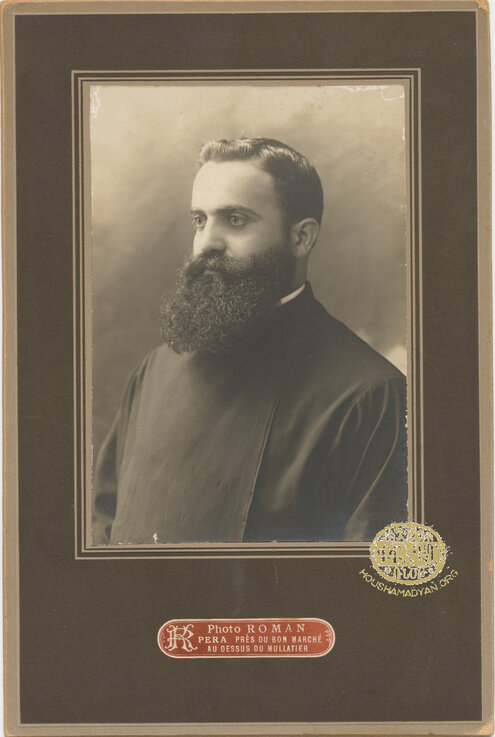

In 1919, Bishop Balakian sent a note behind his portrait (the photo was in his youth) acknowledging Sarkis Bakalian’s aid and for keeping him safe during the Genocide in Adana.

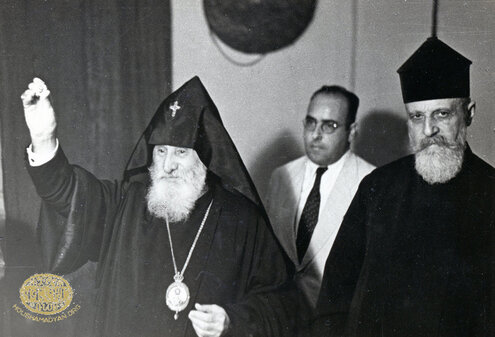

1. and 2. “Authorization”: On September 22, 1932, the Municipality of Beirut granted Pakrat Bakalian the rights to establish a flourmill and pasta factory on Brazil Street, Karantina

Sarkis and his in-laws were close to their church. Parsegh and Dikran Ashekian contributed to the Armenian Apostolic Church. On June 3, 1903, in a letter addressed to the Central Administration [Կեդրոնական Վարչութիւն], Catholicos of Cilicia Sahag II Khabayan [17] writes, “on the initiative of Uzun-Ashekian brothers from Adana (originally from Kayseri) three additional rooms were added” to the Catholicosate building in Sis. [18] When Catholicos Sahag visited Adana in November 1918, Sarkis invited him to stay in his house for a month and a half. [19] Garabed Ashekian confirms in his book: “After the Armistice... Catholicos Sahag Khabayan from Aleppo and the British High Commissioner in the Middle East, Mark Sykes, came to Adana by train on the first occasion they could.” [20] Further, Sarkis Bakalian facilitated the building of Surp Kevork Church in Hadjin in Beirut by purchasing the land; it was located not too far from his factory. Sarkis’s name is on a plaque on one of the four columns of the church.

Sarkis Bakalian did not enjoy the fruits of his labors. Ten-year-old Sirarpie saw Sarkis slumped on the floor and called her mother Marina Ashekian. He died on July 31, 1937 in his home on Khandaq al-Ghamiq in Bashoura, of cardiac failure at the age of 59. [21]

Aztag published a lengthy obituary eulogizing Sarkis Bakalian a few days after the funeral that was led by Archbishop Bedros Saradjian, [22] who was his close friend. A large throng of mourners followed the clergy, family, [23] and notables, including many Muslims who carried his casket on their shoulders all the way to the cemetery chanting, “Ya baba, ya baba Sarkis Bakalian.” Aztag attributed this reverence and gratitude to the deceased, due to his actions during a time of strife and demonstrations in Beirut on November 15, 1936. Sarkis had mediated between Muslims and Armenians and thereby earned the gratitude of both groups. [24]

Sarkis was ahead of his time as a progressive, humanitarian person despite his lack of formal education. Being an independent thinker, he did not join any political party or espouse a specific ideology. His financial and other types of support were for the poor and the powerless. His sons followed his values in their contributions to their Armenian community and national Lebanese interests. In the 1920s and 1930s, there were few Armenian notables in Lebanon, and Sarkis may have been one of them.

In his book, Garabed Ashekian is cold towards his brother-in-law Sarkis Bakalian. They were diametrically opposite in background, personality, skills and talents, but most importantly, the sociopolitical era they lived through; it rewarded one and depleted the other. Garabed was the son of an affluent family, educated in Armenian and French schools, and he enjoyed riding horses, traveling, and socializing. He also dabbled in politics and took to writing later in his life. After Adana, his life was difficult, especially when Romania became part of the Soviet Bloc. His son had settled in Montreal, Canada; he joined him in 1959 when he was 70 years old. The descendants of the Ashekian Clan from Kayseri/Gesaria will be grateful for his book, The History of Uzun Ashekian Clan.

Haiguhi (née Ashekian) Bakalian was widowed at 45 years old. She was very close to her sister Marina and her daughters, Chaké and Sirarpie, grew with their cousins.

Having been displaced from Adana, Mersin and changing so many homes; Sarkis did not want to own any property. His sons, Pakrat and Vasken, followed their father’s footsteps. They always rented apartments rather than build or buy homes in Lebanon. Obviously, the land in Karantina and flourmill was business! Haiguhi, in her own way, did not want to own anything for the home that was unnecessary. She preferred to sit on a simple wooden crate in the kitchen and use another to chop vegetables, cut meat, and such. When her son remarried in 1949, they bought a fridge and new living room furniture.

When Haiguhi settled finally in Beirut in 1930, they rented an apartment in Khandaq el Ghamiq, where many Armenians live. During the French Mandate (1920 to 1943 for Independence of Lebanon), this neighborhood was diverse religiously and ethnically. Khandaq al Ghamiq was close to the souks (markets), government (the Parliament of Lebanon and Place de l’Étoile) and Martyr Square. Also, the Hripsimiants School of Armenian Sisters of Immaculate Conception was for girls. Next to the school was Mr. Antranig Bezdikian’s tailor shop, across the street was the Ouzanian Pharmacy.

Haiguhi and Sarkis would rent a house in Dhour el Choueir in the summer because Beirut was humid and hot. This couple was social, they befriended Armenians visiting from Baghdad, Cairo and Jerusalem in July and August, but the women and children stayed longer. During winter months in Beirut, Haiguhi opened her home up for her female relatives and friends to visit and enjoy her hospitality.

In the 1930s, doctors advised Sarkis Bakalian to rent houses in lower altitude villages because it would be better for his heart, so they started to summer in Aaraya (near Kahaleh and Aley on the road to Damascus) then further in Abadieh for a while.

In 1950, the Bakalians returned to Dhour el Choueir when Pakrat was remarried and had children. They rented a house on a hill south of Hotel Central and the famous Al Kassouf Grand Hotel (which was built in 1930, celebrities including King Farouk, Farid al Atrach, Oum Koulthoum stayed there and the hotel hosted the first Miss Lebanon in 1935). The Bakalians rented the first floor apartment and on the top floor were the Dermendjian family. The father was Levon (a pharmacist, AUB alumni) and the mother Angelle (née Sulahian); were from Ayntab. They had four daughters and a son.

Haiguhi, following her husband and Ashekian tradition, gave refuge to Archbishop Khat Atachabian and another monk in her home in summer 1956 because there was a contested election of the Catholicos of Cilicia (Antelias/Lebanon). The crisis was over the Armenian Church and politics during the Cold War.

Haiguhi was skilled and patient in the kitchen especially in butchering; her mante, sou-boreg, and dolma varieties were famous. At Gaghant on December 31st, she made Topig and Anoush-Abour and the children waited for Gaghant Baba. Further, Haiguhi preserved fruits for the winter such as dates, pumpkins, mulberries, apricots, quince and sweet sudjuk (aka rodjig) to mention a few. Making sweet sujuk, is similar to the method of making candles. Walnuts are strung together and dipped into hot liquid grape mash, layer after each layer. These confectionaries were served for visitors because there were few candy stores in Beirut before 1960s.

Before the Arab Israeli War in 1967, the sisters, Haiguhi and Marina, traveled annually to the thermal hot springs in Hamat [Al-Hamma in Arabic; a mile south of Tiberias], along the Sea of Galilee. Meroujan Shahinian (1906-1973) was their (Sarkis and Haiguhi Bakalian’s) faithful driver and friend since 1930 until his death. He was not married; he lived with his brother and his family in one home. Meroujan and his brother Ghougas were from Afion-Karahisar; his sister-in-law, Haiguhi, was from Adana.

Meroujan Shahinian had two nieces and two nephews. The eldest was Karnig Shahinian (born in Beirut in 1927-died Los Angeles in 2018) dropped school at an early age; however, he acquired his baccalaureate by studying the curriculum on his own. Then he received his credentials in Civil Engineering from the American University of Beirut was successful in his career in Lebanon, Syria, Africa and Jordan. The second child was Tshkhouhie (née Shahinian) Noubar Dedeyan (born in Beirut in 1920—died in 1996); her husband was a fellow compatriot of Afion-Karahisart. The third was Krikor Shahinian (born in Beirut in 1930-died in Beirut in 2009) considered himself an educator by birth and calling, studied in Europe on a scholarship from Djemaran of Hamazkayin and later taught there for many years. His specialization was Armenian and French language and literature; further he was the founder and editor of the literary review “Ahegan.” The youngest was Yeghsapet (née Shahinian) Benyamin Balanzian (1932-2004); she married her husband later in life, Benyamin (an optician) was Vasken Bakalian’s childhood friend and until his death. Karnig, Tshkhouhi, Krikor and Yeghsapet, as well as their children, were very fond of Meroujan and considered him their second father and grandfather. Sarkis and Haiguhi’s children and grandchildren were also fond of Meroujan.

In 1957, Pakrat Bakalian moved his family to Horsh (wood) Badaro, a new development with pine-trees near the Beirut Horse Racing Track. However, members of the Ashekian Clan who escaped from Romania occupied the apartment in Khandaq el-Ghamiq Street. From the early 1950s until the 1960s, they passed through Lebanon for a year or two until they received their visas to emigrate to the U.S.A.

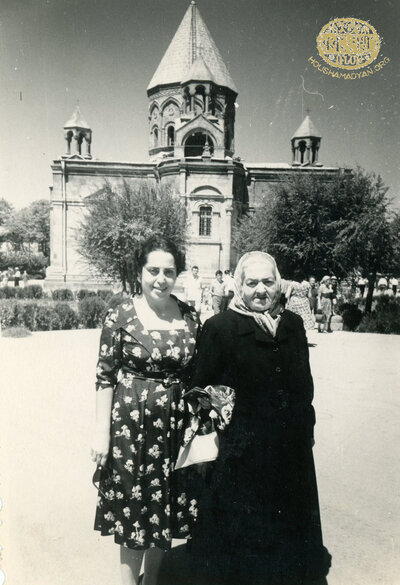

In 1959, Haiguhi Bakalian took a plane from Beirut to Yerevan to visit her daughter Mampile (née Bakalian) Touryantz and meet for the first time her grandson, Garo. Mother and daughter had not seen each other since 1947. After about three months, Haiguhi returned home. Few years later, Haiguhi died in Beit Mery, a summer resort in the Lebanon Mountains, in the summer.

Marina (née Parsegh Ashekian) Bedros Stepan Ashekian (born in Adana, in 1896—died in Beirut in 1974) attended an Armenian school then the French Sisters’ school in Adana. She and her older sister Haiguhi witnessed the Adana Massacre in April 1909; she was 13 years old. (See above "Haiguhi Bakalian").

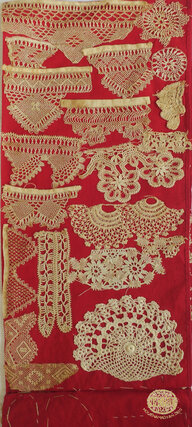

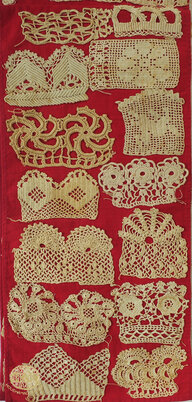

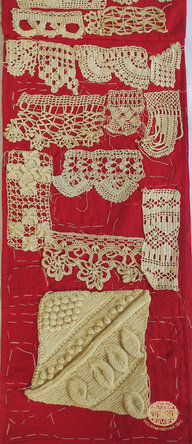

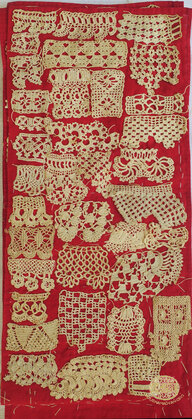

Marina was talented with embroidery and lace as well as cooking and baking. She also had medicinal skills, often in the winter her relatives had the flu, she would use “cupping” on the back of the sick person.

Marina had also medicinal skills, often in the winter when her relatives had the flu, she would use “cupping” on the back of the sick person.

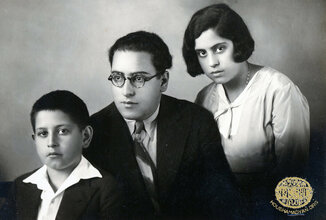

In 1917, Marina married Bedros Stepan Ashekian (born in Kayseri, in 1886—died in Beirut in 1958) in Mersine; she was 21 years old and he was 31 years old. As most of the marriages of this clan, they were related. Bedros’s grandfather was Bedros Parsegh Ashekian, son of the patriarch of the clan and Marina's grandfather was Garabed Parsegh Ashekian.

The couple had a son but died early, and then they had two daughters:

- Chaké (née Ashekian) Najarian (born in Mersine, April 12, 1921—died on February 19, 2007, in New York, NY)

- Sirarpie (née Ashekian) Yaghdjian (born in 1927 in Larnaca, Cyprus)

Marina was close to her sister Haiguhi all her life. The Ashekians lived on the first floor of a beautiful Arte Deco building on the first floor in Khandaq el-Ghamiq; about two blocks from her Haiguhi’s apartment. Marina would drop at Haiguhi's home daily, especially after she was widow and their mother Diruhi moved from Romania to Lebanon in 1938; then she walked to the souks of Beirut to buy the vegetables, meat, fish, bread and other necessities. She returned accompanied with a hammal (porter), carrying a huge basket full of her purchases on his back.

Marina Ashekian's Pattern Crochet Book (8 cloth pieces; made into 16 pages in two sides: 11 are full)

Bedros Ashekian’s parents moved to Adana when he was very young. He studied first at the Armenian school and then at the Friars’ (French Catholic) high school. Bedros’s job was with Shahmir Agha, his paternal uncle’s grocery store near the watch tower of Adana, but it was plundered in 1909. Next he was a clerk at the Ashekian-Bakalian flourmill, which prevented his death from either deportation or conscription during the Genocide. Bedros brought his family to Cyprus after the Cilician Campaign (May 1920-October 1921) when the Turkish National Movement won and the French abandoned Armenian interests and population. He supervised the construction of the Melkonian Educational Institute in Nicosia.

In the early 1920s Sarkis Bakalian had decided to settle in Lebanon; he solicited his brother-in-law Bedros to come to Beirut because he had partnered with Mohammed Abdelkader Tawil to operate a flourmill in downtown Beirut and needed his brother-in-law’s administrative and accounting skills.

After the death of Sarkis in 1937, his heirs, Pakrat and Vasken Bakalian depended on Bedros for advice and his historical memory. In 1943, they established a new corporation, entitled Société Industrielle du Levant, s.a.l. Bedros remained on the Executive Board and his wisdom and experience was invaluable for his nephews until his death in 1958.

In her last decade, Marina lived in her daughter Sirarpie’s apartment across the National Museum of Beirut, and she dotted on her grandsons, Vicken and Patrick Yaghdjian.

Descendants of Harutiun and Annug Ashekian

Vahan Harutiun Ashekian (born Adana, circa 1890—died possibly in Egypt) went to Cyprus during the massacres of Adana in 1909 and then he went to Egypt where he found a job in a steamboat company and traveled between Egypt and the Persian Gulf.

Verjin Harutiun Ashekian (born in Adana, circa 1892—died in Cyprus, circa 1960s) moved to Cyprus with her parents in 1920 after the Cilician evacuation. She was not married and lived in Nicosia until her death.

Descendants of Dikran and Marie Ashekian

Adele (née Dikran Ashekian) Diran Garabed Kazandjian(born circa 1886—died in Baghdad in the early 1960s) attended an American missionary school in Adana. She married Diran Kazandjian (born in Adana circa 1880—died in Beirut, in 1947) in Adana in 1901. He was a graduate of Taurus/Darson College.

They had two daughters and two sons:

- Arpine (née Kazandjian) Salatian (born in Adana, in 1903—died on December 8, 1978 in Athens)

- Haroutune Diran Kazandjian (born in Adana, on August 1, 1906—died on December 10, 1978 in Athens)

- Anahid (née Kazandjian) (born in Adana in 1907—died in 1981 in Baghdad)

- Berdj Diran Kazandjian (born in Larnaca, Cyprus, on September 15, 1921—died on May 17, 1978 in Beirut)

Adele with her husband and children (except their youngest, Berdj, not born yet) her parents and siblings were deported to Aleppo during World War I. (See above “Dikran Ashekian”). After their father’s death in 1920, the Kazandjian family and the remaining Ashekians lived briefly in Larnaca, Cyprus. After hopes of returning to Cilicia were faded, they moved to Beirut. Another reason was that they wanted their children to receive a better education. After few decades in Beirut, Diran Kazandjian died; his widow, Adele, relocated to Baghdad because her daughter, Anahid, lived there.

Murad Dikran Ashekian (born in Adana circa 1891—died in Beirut, circa 1960) received his education in Adana. Murad was close to his cousin, Garabed Parsegh Ashekian, was about two years younger. They enjoyed horse riding and social activities. After the Adana Massacres 1909, he and his family moved to Mersine. His father worked in Adana, and spent with his family on Sundays and holidays in Mersine. When Murad was called to serve in the Ottoman army, his father paid a ransom and he was excused.

Later, the two cousins, still young men, Garabed son of Parsegh and Murad son of Dikran, opened an office under the name "M. and G. Ashekian" in Mersine, but this scheme was not fruitful.

Murad moved with his family to Aleppo during the deportation. They stayed there until the Armistice (1918), and then they returned to Adana. Two years later, his father died. Again Murad joined his family to Cyprus. First he worked with his maternal uncle, Sarkis Bakalian. When Bakalian moved to Beirut, Murad’s business failed. When his siblings also settled in Lebanon, he followed them, where he continued to start new deals; for example, he imported mechanical thread spinners, as well as attempted to sell machinery in Aleppo. Murad was not successful in his plans, neither in Larnaca nor Beirut.

Murad passed away in Beirut, a bachelor, and was buried next to his mother, whose grave is located to the immediate left of the gate of the Armenian cemetery of Beirut. His sister Zaruhi died after him.

Lousadzine Dikran Ashekian (born in Adana circa 1895—died in Beirut, October 1, 1968) was educated in a francophone school in Adana, played the piano, studied painting, embroidery, crochet and other skills. She was not married; she lived in her father’s house. in Adana until 1920. In Cyprus and Lebanon, she lived with her sister Zarouhi and her brother Murad in Larnaca and Beirut. She enjoyed the company of her family.

Zarouhi Dikran Ashekian (born in Adana circa 1897—died in Beirut in 1963) like her sisters, she attended French school in Adana. They spoke Armenian, Turkish, French, and must have learned some Arabic when they settled in Lebanon. Zarouhi and Lousadzine read the French magazine, Mode et Travaux (founded in 1919 Paris). She played the piano, painted, and embroidered as well as crocheted fine lace. She was not married, but enjoyed the company of her nieces and nephews and their children.

Tsoline (née Dikran Ashekian) Garabed Djerdjirian (born in Adana in 1901—died in Marseille in the 1960s) lived with her family in Adana until the Adana Massacres, then moved to Mersine. During the Genocide, their family was deported, but her father managed to stop in Aleppo. After the Armistice (1918), they returned in Adana. After her father’s death in 1920, her mother and siblings lived briefly in Cyprus then settled in Beirut.

In 1931, Tsoline married Garabed Djirdjirian in Marseille. As the majority of the matrimonies of these families, the groom was kin too. The bride needed a chaperone to accompany her to Marseille. Her aunt, Nevrig (née Ashekian) Telalian was a widow and had no children, so she was the right person to accompany her to France. The wedding was at Cathédrale Apostolique Armenienne des Saints Traducteurs.

It is interesting that on October 25, 1931, Bishop Krikoris Balakian became the cleric of Saints Traducteurs in Marseille. During the Genocide, Sarkis Bakalian aided the Bishop to escape to Europe. He must have been surprised to find an Ashekian in his church and may have baptized Tsoline and Garabed Djerdjirian’s son.

Tsoline and Garabed had two sons:

- Karnig/Charles Garabed Djirdjirian (born in Marseille in 1932—died in Marseille on December 16, 2017)

- Denis Garabed Djirdjirian (born in Marseille in 1936)

Descendants of Mihran and Gyulena Ashekian

Eliz (née Mihran Ashekian) Levofet M. Pambukdjian (born in Adana, circa 1899—died in Zahle, Lebanon, in circa 1930s) married Levofet M. Pambukdjian of Kayseri (circa 1920). They had a daughter.

Mayda Levofet Pambukdjian (born in Lebanon, circa 1922—died in Lebanon).

Unfortunately, Eliz died young and left her husband a widower and her daughter, Mayda, without a mother. Levofet Pambukdjian was a social and successful businessman; he later operated the “Minoterie (mill) Pambukdjian” along Beirut River. Such a good-producer should be kept in the family; so his mother-in-law, Gyulena (née Garabed Palamutian) Mihran Ashekian, encouraged Levofet to marry his sister-in-law, Victor.

Levofet Pambukdjian may have been the son of Pambukdjian who had two factories producing ice and cotton in Adana. Puzant Yeghiayan confirms in his book that there were four ice factories in the city: Ashekian-Bakalian and another Armenian, Pambukdjian-Donigian; also Adana families that had mechanical cotton gins, were Ashekian-Bakalian, Pambukdjian-Mardigian, and two others Armenians. [25]

Louise Mihran Ashekian (born in Adana in 1901—died in Beirut in 1970s) lived in Adana with her family and grandparents and their uncles’ families. After the Adana Massacres, the family moved to Mersine. In 1919, her mother moved her daughters to Cyprus and few years later, they lived permanently in Lebanon. She was not married and lived with her sister Paruhi.

Victoria, called Victor (née Mihran Ashekian) Levofet M. Pambukdjian (born in Adana, circa 1904–died not known) lived in Adana in a large house with her grandparents and uncles’ families. After the Adana Massacres, their family moved to Mersine. Her father died when she was about two years old.

In 1919, her mother and sisters moved to Cyprus. A few years later they settled permanently in Lebanon. When her eldest sister Eliz died, Victor married Eliz’s widower, Levofet Pambukdjian. Victor raised her niece Mayda, and the couple had a son and two daughters of their own:

- Mihran Levofet Pambukdjian (born in Beirut, circa 1935)

- Lizet Levofet Pambukdjian (born in Beirut, circa 1937)

- Miranda Levofet Pambukdjian (born in Beirut, circa 1939)

Paruhi (née Mihran Ashekian)Sarkis Bedros Ourfalian (born in Adana in 1906—died in Beirut, circa 1980s) like her sisters she was born in Adana and her birth was just before her father’s death. The family of Mihran, like the other Ashekians, moved to Cyprus and then settled in Lebanon.

Paruhi married Sarkis Ourfalian (born in Mersine, born circa 1910—died in Beirut, 1961) who was educated in Basra, Iraq. He was a social fellow and had a position in a British company. He moved to Tripoli, Lebanon, finally settled in Beirut. Unfortunately, he died prematurely in 1961.

Paruhi and Sarkis had a son and daughter:

- Peter Sarkis Ourfalian (born in Beirut, circa 1949)

- Bella Sarkis Ourfalian (born in Beirut, circa 1953)

When their father died, they were children. According to Garabed Ashekian’s book, Levofet Pambukdjian supported them.

The Fifth Generation in Lebanon

Descendants of Sarkis & Haiguhi Bakalian

Pakrat Sarkis Bakalian (born in Mersine, on December 24, 1913—died April 25, 1976 in Baabdat, Lebanon) was the second son of Sarkis and Haiguhi; unfortunately, his brother Torkom died very young, probably in 1914.

During World War I, the Ottoman Empire’s Army took over the Ashekian-Bakalian flourmill of Adana to feed bread to the troops. During the Genocide, the Ashekians and Bakalians were not deported while many Armenians were exiled to the desert and died.

Pakrat’s father had befriended a high officer who was dispatched at the flourmill; in 1919, this man tipped off Sarkis to leave Adana immediately. The Bakalians and some of their relatives left Cilicia with most of their portable wealth. They went to Cyprus and lived in Larnaca for few years. Sarkis Bakalian decided to build his next flourmill in Beirut.

Pakrat must have started an elementary school in Cyprus; in Beirut he attended the Prep School, which was affiliated to the American University of Beirut (AUB). In 1936 the Prep School became International College (IC).

Pakrat graduated with a Bachelor’s in Business Administration at AUB in 1936. Among his Armenian classmates at AUB were Gulbenk Avedis Gulbenkian (born in Talas in 1913—died in Beirut circa 1979) and another friend was Hagop Garabed Touryantz; he was from Egypt and few years later he married his sister Mampile Bakalian.

A year after Pakrat’s graduation from college, his father Sarkis Bakalian died leaving the business to his sons: Pakrat was 23 years old and Vasken was 16 years old. Vasken continued his schooling until his baccalaureate at a Jesuit school. However, uncle Bedros Ashekian was a trusted senior in the business.

In 1943, the Bakalians established a new enterprise, incorporated with a 75-year license, called Société Industrielle du Levant, s.a.l. According to the articles of incorporation and bylaws, the purpose of this firm was for buying, selling and processing all types of grains. Then, SIDUL shareholders decided to increase the capital of the company to 1,500,000 LL, thus adding 700,000 new shares in February 1951. In June 1952, Cheikh Boutros El-Khoury and Phoebus B. Kyprianou bought a small amount of SIDUL shares and were appointed to the Executive Board. Vasken Bakalian and Bedros Ashekian remained as members and Pakrat as president. Additionally, the corporation upgraded its capacity to 275 tons every 24 hours with new Bühler-MIAG machines.

In 1939, Pakrat married Marie Jacob Vosgerichian (born in 1922—died in New York in 2014); her parents were Ashkanoush and Artin/Jacob Vosgerichian from Ayntab. They had a daughter they named Tiana. [26]

Marie was a very modern young woman, spoke several languages, enjoyed tennis and was a progressive thinker, ahead of Armenians and even the majority of Arabs in Beirut. Their marriage did not endure. When they separated, Marie took her daughter with her. Eventually when her divorce finalized in 1946, she immigrated to the U.S. Later she married Samuel H. Toumayan, a publisher and editor of Nor Ashkarh (New World), who adopted her daughter.

The 1940s Pakrat was divorced with time on his hands. He put his energy in the Armenian causes of the decade. On November 25, 1945, radio announcements disseminated the news from Moscow, Yerevan, London, Paris, and Beirut: The Soviets called for repatriation, Nerkaght in Armenian, because they had lost significant population during World War II. Soviet delegates were sent to Armenian communities in the diaspora, especially Lebanon, Syria, Greece, Egypt, and Turkey, to manage the relocation and assist local boards. For example, in Beirut Pakrat Bakalian was the first treasurer of the Repatriation Committee and Hagop Touryantz was in charge of transportation.

In the fall of 1946, Pakrat received an official invitation to visit Soviet Armenia. He traveled by car through Iraq and Iran visiting classmates from AUB until he arrived in Yerevan.

After Armenia SSR, Pakrat Bakalian went to Moscow; then took a ship on the Black Sea to Beirut. However, he stopped in Romania to visit his maternal uncles and other relatives. On the ship, Pakrat met Julia Bazirganian, the daughter of a doctor from Istanbul on the ship. She grew up with nannies, spoke Armenian, Turkish, French and English, attended American Junior College for Women in Beirut, but was not a serious student. In the 1950s, she married Sarkis Bezdikian, the mayor of Bourj Hammoud, and became a close friend to Sona (née Allahverdi) Bakalian.

Pakrat’s friends wanted his opinion of Armenia SSR. He said: “It is not for people like me; however, folks whose resources are limited may try Armenia.” Nonetheless, Hagop Touryantz was the leader of a convoy that left Port Beirut on July 4, 1947; his wife Mampile (née Bakalian) Touryantz and a ship full of Armenians were repatriating to Yergir (country).

The repatriation was a disaster for many. The majority of those who arrived in Armenia came from the Ottoman Empire, Genocide survivors and refugees; they did not have strong roots in their new country. They went for patriotism and the promise of better economic prospects. Soviet’s assurances and propaganda were false; conditions were harsh, food sparse, life miserable and politics oppressive. Moreover, the newcomers were called the derogatory akhbar (brother). Eventually, many of the descendants who repatriated to Armenia in 1947 returned back to the West starting in the 1980s.

In his book, Garabed Ashekian explains Touryantzs family's sequel. Hagop was employed “as an economist in Armenia.... They own a two-story private home in Yerevan, along with a car, and they spent their vacations in Sochi. Unfortunately, he was unable to establish a warm environment for himself in Armenia and returned to Beirut in 1965.” [27]

The Touryantz family was frustrated; they imagined that Mampile’s brothers who had a profitable business in Beirut could change their environment. Actually, the brothers supported their sister. On the ship that took them to Armenia, the Touryantz carried a large cargo that contained everything they needed to build a house, including tools, furnishings, clothing, etc. Also, big packages were dispatched from Beirut to Yerevan contingent to Soviet policies, they included clothing, pantyhose, cosmetics, and other items scarce in the USSR; and these were bartered on the marketplace.

Hagop, Mampile Touryantz and their son Garabed settled in New York In 1967. Hagop wrote a book, Search for a Homeland [28] about his experiences behind the Soviet curtain.

In 1949 Pakrat Bakalian married Sona (née Allahverdi) Bakalian (born in Istanbul, May 25, 1922—died in New York, March 27, 2006). They were second cousins who had never met—he grew up in Beirut and she in Istanbul.

They had four children; the last pregnancy was a set of twins, Houri died as a newborn:

- Anny Bakalian (born in Beirut, in 1951) received PhD in Sociology at Columbia University, wrote two books and many articles and built the Middle East and Middle Eastern Studies (MEMEAC) at the Graduate Center, City University of New York.

- Sarkis Bakalian (born in Beirut, January 10, 1952—died in Beirut, on November 6, 2009) administrator of SIDUL in Beirut.

- Ruby (née Bakalian) Gulian (born in Beirut, in 1953) received a Master’s in Archeology from the American University of Beirut and a certificate in cooking from the New York Restaurant School; and with her husband Hirant are active in the Armenian community in New York/New Jersey.

The Bakalians lived in a four-generational household in Khandaq el-Ghamiq as the children were growing up. In 1957, they moved to a modern apartment in a new “suburb,” Badaro.

Pakrat continued involved in Armenian causes. He was an Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) Asbed and one of the founders of Veradznount (Renaissance) association, with the goal to promote the Armenian and Arab cultures.The clubhouse of Veradznount was located on the first floor of the Zighby building on Mar Mikhael, across the Electricity of Lebanon building. The organization sponsored sports teams including Sevan, the cyclist troupe that competed with other groups in Lebanon. There was also an ensemble that featured Armenian music, songs, and theatrical soirees. Also the women committee’s offered cooking classes and English classes. They would also, organize visits from Santa Claus, who would appear with gifts for needy children at Christmas.

1.Veradznoont Club, 26 December 1953. Sitting around the table, from left: Anny Nubar Khoubesserian (child), Nubar Khoubesserian, person not known, Chaké (née Ashekian) Najarian, person not known, sister of Nigoghos Hagopian, Makruni/Margo (née Mikalian) Preutian, Alice Hovsepian, Sona Bakalian. Pakrat Bakalian is standing on the right of Chaké.

2.1953, Veradznoont association: speakers from Soviet Armenia

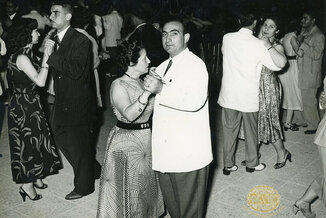

3.1954, Veradznoont association at a dance in a hotel in Beirut

During the Cold War, tensions exploded amongst Armenians in Beirut in February 1956 during elections of the Catholicos of Cilicia in Antelias. The Soviets sent Catholicos Vasken of Echmiadzin to Beirut hoping to elect a pro-Echmiadzin bishop. Opposed to the Soviets were the President of Lebanon, Camille Chamoun, the Armenian Parliamentarians, and the ARF; they supported the cadidacy of Archbishop Zareh of Aleppo. The contest split the Armenian Apostolic Church into two ideological camps, though the split was not theological. Dual jurisdictions divided the diaspora in churches, institutions, schools, press, athletic groups, scouts, etc, especially in the United States.

A minority felt the ARF had hijacked their Church. For example, Pakrat Bakalian and his friends from Veradznount stopped worshiping at Saint Gregory the Illuminator Cathedral in Antelias and went to Surp (Saint) Kevork in Nor Hadjin for sacraments and holy days. Clergy loyal to Echmiadzin were homeless and had to find temporary shelter until a rental apartment was arranged for them.

Zaven Messerlian in his book shows that through the 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s Pakrat Bakalian was an active leader in Armenian and Lebanese life and politics. In the mobilization for the 1947 elections, Pakrat’s name is mentioned on a list—United Armenian Front—opposing the ARF Party. They proposed to improve Armenian schools, construct streets in Armenian neighborhoods, improve health, and assign “posts in the state administration for Armenians who were competent and had a good command of the Arabic language.” [29] In the 1951 elections, Pakrat was again a member of the Armenian Front. Pakrat visited President Fouad Chehab, on May 23, 1959 with a delegation of Armenian independents.

Messerlian states that this was less than a week after “Chehab paid a formal visit to the Catholicosate of Antelias, a move which was interpreted to mean that no change in the status quo of the Armenian Church could be expected in Lebanon any time soon.” [30] No doubt, these prominent men wanted to register their opposition to the ARF politicians, yet they want to confirm their loyalty to Lebanon. In addition to political meetings, the brothers Pakrat and Vasken Bakalian attended a banquet organized by Veradznount on June 28, 1953 supporting the candidacy of Dikran J. Tosbath (1911-2002) on Raymond Eddé’s National Bloc. Zalfa Chamoun, the First Lady of Lebanon, attended the event.

After the death of Catholicos Zareh I (born in Marash in 1915—died Beirut in 1963), the Catholicos of Echmiadzin Vasken I invited the successor Khoren I (Catholicos of the Holy See of Cilicia, 1963-1983) to meet in Jerusalem. The conclave reconciled the two holy sees officially, but daily practices did not change. Archbishop Khat Achabahian who had led the protest in 1956 was living outside a monastery and in poor health. He sent a delegation to Antelias offering congratulations to the new Catholicos on November 11, 1963; among the delegates was Pakrat. By the end of the year, Khat was allowed to spend his last years among his congregation, but the other clergymen of the opposition were not integrated. This was the last time Pakrat Bakalian is mentioned in the press.

By the late-1960s, Pakrat Bakalian had retired from active involvement in the Armenian community in Lebanon. This new lifestyle may have coincided with his first heart attack in the spring of 1967, the dissolution of Veradznount, or possibly he was looking for other challenges.

Pakrat was rewarded for his service to the Armenian community and Lebanese industry. In February 1947, the Catholicos of Echmiadzin, Kevork VI (Cheorekdjian) [1945-1953], had bestowed on him the Saint Gregory the Illuminator Medal and an encyclical for his role in the repatriation.