The Armenian Community of Kalamata (1921-1947): Poverty, Resistance, Repatriation

Author: Mike Tsilingirian. Translator: Simon Beugekian, 11/05/22 (Last modified 11/05/22)

The history of the Armenian community of Kalamata spans approximately three decades. It is not well-known in modern Armenian circles. Due to the lack of research, it has been forgotten over the years.

This short article provides an overview of the approximately 25-year history of this community. Hopefully, this work will spur others to conduct in-depth studies on the intriguing history of this city’s Armenian population.

The history of the Armenian community of Kalamata spans approximately three decades. It is not well-known in modern Armenian circles. Due to the lack of research, it has been forgotten over the years.

This short article provides an overview of the approximately 25-year history of this community. Hopefully, this work will spur others to conduct in-depth studies on the intriguing history of this city’s Armenian population.

Armenians first settled in Kalamata in 1921, when 280 Armenian refugees arrived in the city. They came from the area of Nicomedia (Izmit) of the Ottoman Empire. They had stayed on the island of Lemnos for a short period of time, after which they moved to Kalamata. The flow of refugees from Asia Minor to Kalamata greatly increased in 1922, and another 200 Armenians arrived in that year.

The first reference to the Armenians of Kalamata in the local Greek press seems to have been recorded on January 8, 1923, when a protest was staged in the city against the agreement between the Turkish and Greek governments regarding the obligatory exchange of refugees. The protesters, waving black flags, gathered in front of the “People’s School” and handed a note of demands to the authorities, in which they expressed their opposition to the planned exchange. Among the signatories of the letter were the Istanbul union of refugees; Gh. Ghregorakis, K. Moskhoyanidis, and S. Liakkakis on behalf of Pontic refugees; Gh. Zakharof on behalf of refugees from Asia Minor; O. Ghrighoriadis on behalf of Thracian refugees; and Ghevont Der Ghougasian and Zareh Rafayelian on behalf of Armenian refugees. [1]

In 1924, under the pretext of reducing the density of the refugee population in Macedonia and western Thrace, the Greek government launched a resettlement program that officially applied to all refugees, regardless of national origin. But in practice, it soon became clear that the program specifically targeted Armenian refugees. In fact, this action was taken by the Greek government in response to the rising tensions between Greece and Bulgaria due to a border dispute. The Greek authorities saw the Armenian refugees as suspicious elements who may take a pro-Bulgarian stance if war broke out, and thus wished to remove them from the border area. Consequently, in the summer of 1924, about 5,000 Armenian refugees were deported from Alexandroupoli (Dedeaghadj), Komotini (Gumuldjina), Serres, Drama, and Kavala. The refugees were resettled in the Peloponnese, with about 600 resettled in Kalamata. [2]

In that same year, thanks to the efforts the Lord Major Foundation, about 300 Armenians from Kalamata were resettled in the city of Heraklion in Crete. These Armenians were employed in the construction of the quay of the city’s port. Around the same time, many other Armenians left Kalamata and moved to other Greek cities or abroad, particularly to France.

In 1934, more than 200 Armenian families lived in Kalamata. Most of these Armenians were craftsmen or farmers. Most of them hailed from historic Bithynia (Boursa). A total of 35 families hailed from Armash, 25 from Yenidje, and others from Arslanbeg, Izmit, Adapazar, Bardizag, and the Medz Nor Kyugh. [3]

This same period saw Armenian refugees settle in the villages of the Kalamata area, including 50 Armenians in Messene, 10 in Kyparissia, and a small number in Meligalas. [4]

The Parapighmata Camp; Its Church and the Two Schools

The majority of the Armenians of Kalamata (135 families) lived in a refugee camp located on the western coast of the city. The area was the property of a Greek named Kordias, and it is known as Kordias to this day. In the past, it had been the site of a military barracks. Some of the refugees had settled in the half-dilapidated, wooden buildings of the old barracks. The rest had built tin huts. [5] These gave the camp its name, Parapighmata – Greek for wooden or tin hut.

The camp was very close to the sea, in an area extremely unfavorable for farming, as frequent storm surges would cause seawater to inundate the arable land nearby. Notably, Greek sources never called the area Parapighmata. This name only appears in Armenian sources. Some of the extant Greek maps from this period call the area Armenika, which translates into “Home of the Armenians.”

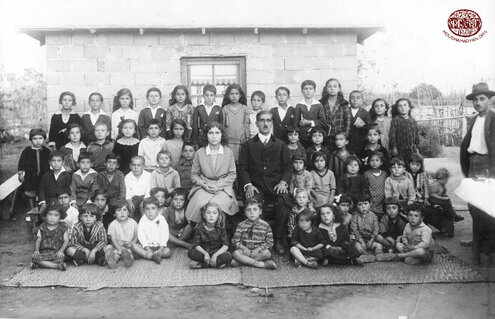

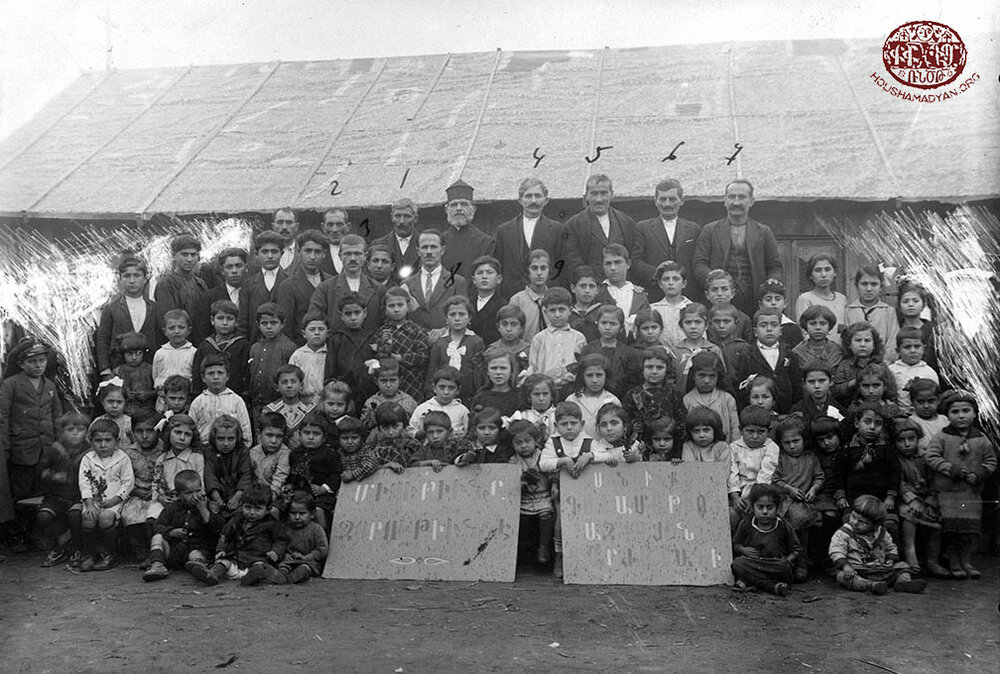

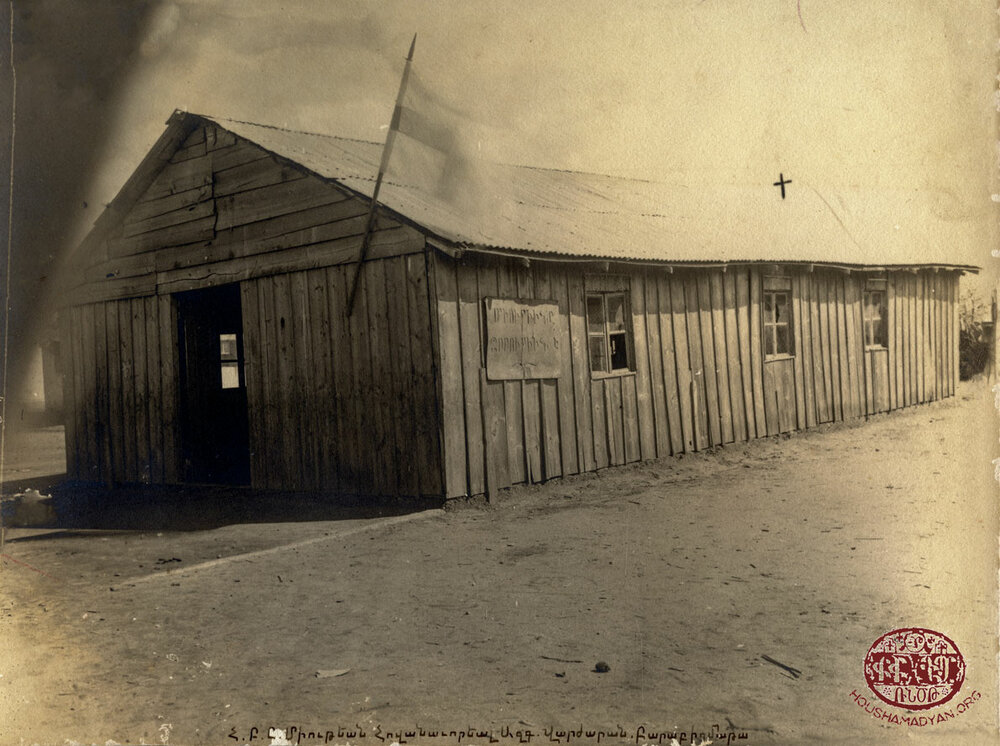

A wooden church was built in the camp in 1923, usually called a chapel in written sources. The same building also began operating as a school in 1924, with an enrollment of 70 to 90 pupils. The school received financial support from the local chapter of the Armenian Red Cross, as well as the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU). The photograph of the school, which can be found on this page, shows the flag of the Red Cross waving from the roof, as well as a banner reading “Unity is Strength,” the motto of the AGBU, on the wall. This school had the largest enrollment of any educational institution in the refugee camp. Among the teachers who served there, sources mention Vrtanes Takvorian. [6] The school continued to operate until 1943, when the fire that raged through the camp burned the building to the ground.

A second Armenian school also operated in the Parapighmata camp, called the Rosdomian School, under the aegis of the Armenian Blue Cross. This school frequently faced administrative and financial difficulties, which eventually forced its closure for a year in 1934. Enrollment ranged from 25 to 30 pupils. [7] Among its faculty were Roza Hayrabedian [8] and Onnig Sharabkhanian (born in Medz Nor Kyugh). Onnig’s son, Mardig Sharabkhanian, born in Kalamata, later served as a teacher in the Armenian school of the Dourgouti/Fix neighborhood of Athens. Later, he moved to Canada, where he served as the principal of the Armenian school in Toronto.

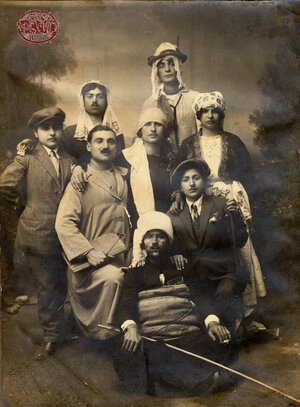

The hall of the Rosdomian School hosted many cultural events, including popular theater performances. For example, on February 7, 1930, amateur Armenian actors organized a performance of Avarayri Ardziv [The Eagle of Avarayr] there. The role of Vartan was played by Terenig Menanian, and the role of Vasag by Onnig Sharabkhanian. Other actors included Sarkis Garabedian, Sdepan Aslanian, Armenag Ovanian, Yenovk Ovagian, Vaghinag Baltayan, Onnig Krikorian, M. Ayvazian, and Kh. Papelian. [9] In 1931, on Easter Sunday, the school’s hall hosted a play, called The Immortal Jirayr, about the life of Armenian revolutionary Jirayr (Mardiros Boyadjian, 1856-1894). The cast included Onnig Sharabkhanian, A. Papelian, M. Gaganian, O. Manougian, Kh. Papelian, Kh. Der Ghougasian, and V. Kabadayan. [10] Both plays were enjoyed by a large audience.

Armenians in the city of Kalamata; the Aramian School

While the majority of the Armenians of Kalamata lived in the refugee camp, approximately 40 to 60 families lived within the borders of the city, especially in the Ypapanti (Candlemas) neighborhood. [11] According to figures from 1939, the number of Armenians living in the city, excluding those living in the refugee camp, was 196. [12] In the early years after their arrival, an Armenian refugees’ committee operated in the city, and provided financial assistance to indigent refugees.

In 1929, the Aramian co-educational kindergarten and elementary school opened its doors in Kalamata. It was housed in a rented building, very close to the Ypapanti Greek church. The school received financial assistance from the AGBU and the Gullabi Gulbenkian Foundation (New York). Enrollment ranged between 40 and 60 pupils, and the school principal was P. Khachigian. Among the teachers who worked there, sources mention H. Kasbarian and Hovhannes Demirian. [13] The school was forced to close after the German occupation of Greece in the Second World War. [14]

The AGBU founded a chapter in Kalamata in 1929, with 29 members, including residents of both the city and the refugee camp. The first executive board of the chapter consisted of Vrtanes Takvorian (chairman), Hrant Simonian (secretary), Haroutyun Avakian (treasurer), Movses Mavian, and Khachig Yanakian. At a later time, the executive board consisted of Vahram Pesdildjian (chairman), Khachig Yanaksian (secretary), Hovhannes Chinarian (treasurer), Nshan Chakalmazian, and Onnig Bodourian. In 1930, a separate chapter of the AGBU was founded in the refugee camp of Parapighmata. Its executive board consisted of Hagop Ohanian (chairman), Hrant Simonian (secretary), Varteres Parseghian (treasurer), Vrtanes Takvorian, and Haroutyun Avakian. [15]

Community Life, Crafts, Poverty, and… Football

Father Ghevont Der Ghougasian served as the visiting priest of the Kalamata Armenian community. In 1927, he settled in the city permanently. The last priest known to have served the community was Father Hagop Hakalmazian, whose name is mentioned in clerical correspondence from 1943.

Among the organizations active in Kalamata’s Armenian community were the Armenian Relief Council (a communist organization), the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), and the AGBU. The neighborhood councils were controlled by the Armenian Relief Council. [17]

Various conflicts and disagreements were frequent within the community. This was a common phenomenon in the new Diasporan Armenian communities that began growing in the 1920s. The conflict was rooted in divergent attitudes towards Soviet Armenia, something that had created a rift between Armenian organizations and political parties throughout the Diaspora.

This tension was particularly palpable in the small Armenian community of Kalamata, as evidenced by the two rival schools that operated in the refugee camp. The church/school was affiliated with the AGBU and the Armenian Relief Council, while the Rosdomian School was affiliated with the ARF. In 1934, the election of a local priest by the neighborhood council brought these tensions to a boil, as the two candidates for the position, Haroutyun Khacherian and Sahag Hakalmazian, represented the two opposing factions within the community. As a result, on August 26, the refugee camp witnessed violent clashes, during which the previous chairman of the neighborhood council, Sdepan Mouradian, was seriously injured. [18]

There are short mentions of the activities of the ARF in Kalamata in Greek-Armenian press of that period. For example, in 1928, ARF Day was celebrated with great ceremony at the home of M. Manouelian. H. Der Ghougasian delivered a speech, and the attendees sang revolutionary songs and recited poetry. [19]

As for the activities sponsored by the Armenian Relief Council and the AGBU, we know that in 1934, an event was organized in the hall of the Aramian School to commemorate the passing of Father Ghevont Tourian, killed in New York. Among the speakers were V. Demirian, V. Takvorian (chairman of the local chapter of the AGBU), P. Khachigian (the chairman of the local chapter of the Armenian Relief Council), H. Demirian, and Reverend Kayayan, representing the local Armenian Evangelical Church. This event had special significance, as Father Ghevont Tourian was assassinated by members of the ARF. [20]

Most of the working-age Armenians in Kalamata were workers or craftsmen. But after settling in the Greek city, to make a living, they had become farmers, porters, cobblers, sandal makers, tinners, antique dealers, and carpenters. Others would collect wood from the nearby mountains and sell it in the city. [21] Many of the men worked in the nearby wine presses. Still others were builders/handymen. There was a factory at a distance of half an hour’s walk from the refugee camp, where fig was dried and preserved. According to figures from 1931, 20 Armenian women worked in the factory. [22]

Many of the Armenians living in the refugee camp were unemployed, and poverty was rife among them. [23]

In the mid-1920s, the Armenians of Kalamata founded their own football team. Its official name was the Association of Armenian Athletes of Kalamata, but the Armenian press generally referred to it as Ararat. The team was a member of the Greek football league. In 1929, the executive board of Ararat was chaired by T. Sharabkhanian, and the first secretary was D. Minasian. In 1930s, the main team’s players were A. Mavian, H. Ohanian, V. Baltayan, M. Ayvazian, S. Papazian, Z. Chinarian, Kh. Mikayelian, Y. Khronopoulos, Onnig Sharabkhanian, M. Der Ghougasian, P. Ohanian, Sh. Krikorian, S. Simonian, and V. Der Ghougasian. Ararat also had a secondary team. [24]

German Occupation (1941-1944): Resistance and the Burning of Parapighmata

The extant oral history of the Armenian community of Kalamata indicates that during the Second World War, when Greece was occupied by Nazi forces (1941-1944), the community actively participated in the resistance movement.

Yeranouhi Mgrdichian, a former resident of the camp, tells of a local guerilla squad, led by Manoug/Manolis Katrdjian, nicknamed “Armenis” [“The Armenian”] by the local Greeks. At a time when the entire country was in the throes of a famine, Manoug and his squad would, at night, make forays into the city and break into food supplies. They would inform the people in advance, so that they could come and take the food they needed. [25]

According to Yeranouhi Mgrdichian, when the Greek Civil War (Emfýlios) began after the Second World War, pitting communists against right-wing groups, Manoug, too, participated in the fighting as a sworn communist. By then, the Monarchist Greek government had issued an arrest warrant for him. He went into hiding in Kalamata. Manoug’s escape from the city was an adventure in its own right. An Armenian had died around that time in Kalamata, and his funeral ceremony was being organized in Athens. Manoug was secretly sneaked into the coffin that was reserved for the deceased. In this way, he was able to safely make his way to Athens, where he continued his underground activities until the start of the repatriation movement to Soviet Armenia. Manoug joined the repatriation caravans, and like many other Armenian communists, left for Soviet Armenia.

Various sources verify the significant participation of the Armenians of Kalamata in the local anti-Nazi resistance movement. For example, in December 1943, 14 Armenians were detained in Kalamata jail. These Armenians were most probably members of the resistance. Another well-known event occurred on November 24, 1943. On that day, ten individuals were executed by firing squad in Kalamata by the Germans. This was an act of retribution for an attack by the resistance that had wounded a German soldier. Those who were executed included the following Armenians: Khachig Arslanian (born in 1918, in Ferizli (near Izmit)), Hagop Fedeyan (aged 24), and Vahe Mavian (born in 1901, in Armash). [26] On February 8, 1944, the city of Kalamata was surrounded by German forces in an operation that ostensibly aimed to arrest suspected members of the resistance. This event is known as the Kalamata bloko (blockade). According to official Greek sources, 153 of the locals who were arrested were later shot. Among the victims was one Gayan Malivian. This was an Armenian whose name had been transliterated into Greek and thus corrupted. Unfortunately, we were not able to ascertain his true name. Other sources indicate that the death toll of this operation was much higher, possibly reaching 520.

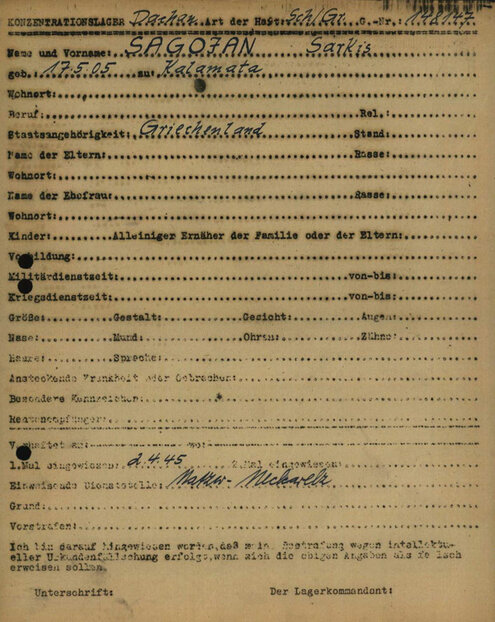

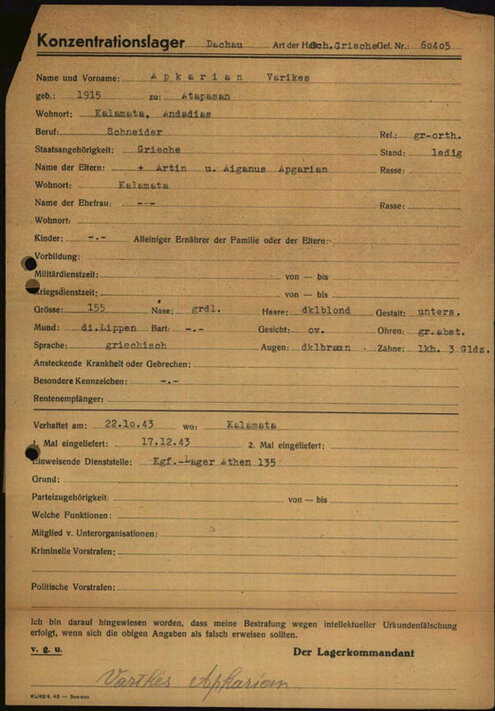

According to an article that appeared in 1946 in the Greek-Armenian newspaper Nor Gyank, 12 of the Armenians arrested during the bloko operation of Kalamata were sent to concentration camps in Germany. Among them were Smpad Ghazarian (born in 1909, in Armash) and Nshan Chiftdjian (born in 1923, in Kalamata). They were both active in the resistance movement. Both were interned at the Dachau concentration camp, and were later killed there. Of the 12 Armenians identified in the article, only five returned to Greece after the war. Three of them were named as Vartkes Apkarian (born in 1915, in Adapazar, and interned at Dachau), Sarkis Sogoyan (born in 1905 and interned at Dachau), and Hovhannes Mgrdchian. The same article also mentioned Hmayag Mavian (18 years old, form Armash) and Karnig Kasbarian (23 years old, from Arslanbeg), both arrested during the same bloko operation, and who remained missing. They were most probably killed by the Nazi forces. [27]

In their efforts to eradicate resistance, the Nazis were ruthless in their punitive operations. They demonstrated this once again in April 1943, a horrific and terrible month in the history of the Armenians of Kalamata. In that month, German Nazi forces entirely burned down the Armenian refugee camps of Parapighmata, razing it completely to the ground. The residents of the camp were forced to seek shelter in the city, in cellar quarters that lacked the basic necessities of life. [28]

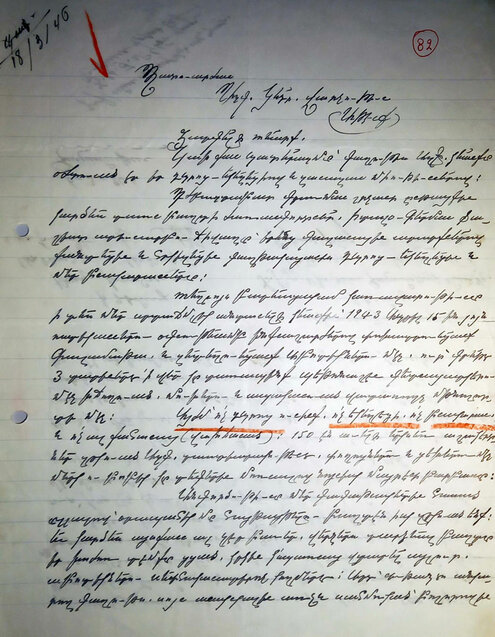

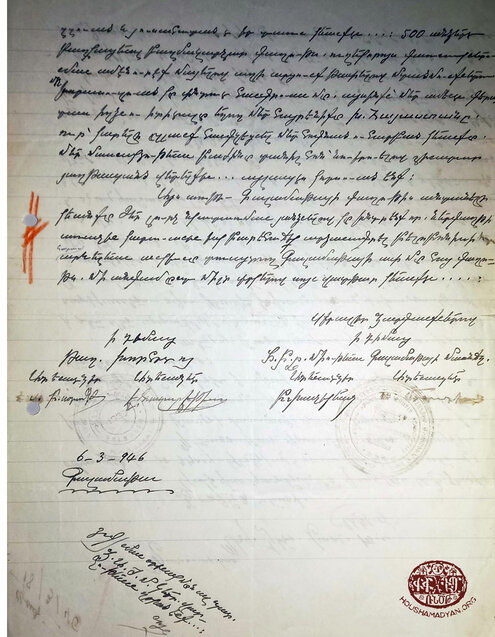

A letter written by the neighborhood council of the Armenian community of Kalamata and the local chapter of the AGBU to the Armenian Central National Council in Athens; dated March 6, 1946. The letter, written after the end of the Second World War, provides details of the experiences of the Kalamata Armenian community during the years of Nazi occupation: “Unfortunately, during the occupation, we were once again the victims of a terrible fate, and the Italo-German fascist monsters savagely destroyed and burned the camp’s school/church and our homes” (Source: Archives of the Armenian Prelacy of Greece, Athens).

The Last Chapter in the History of the Community; Repatriation

Contemporary Armenian and Greek press reports regarding the Armenian refugees of Kalamata give the impression that these refugees, especially those residing in the Parapighmata camp, lived on the fringes of society. Notably, the central Armenian leadership in Athens did not provide the community with the necessary assistance. The Armenian schools of Kalamata constantly faced financial difficulties, the population was extremely poor, and the community was plagued by frequent and insuperable social problems. The Greek press only mentioned these Armenian refugees whenever one of them committed a crime or broke the law. In such cases, as expected, the narrative about the refugees was negative.

In light of these difficulties and having just survived the calamities of the Second World War, the community now experienced one of the most important events in the history of the Armenian population of Greece – the repatriation movement to Soviet Armenia (nerkaght). In 1946 and 1947, the absolute majority of the 500 Armenians [29] of Kalamata repatriated to Armenia. Only a few Armenians families stayed behind, and even these soon left Kalamata and moved to Athens. [30]

We could conclude this article by asserting that with the 1946-1947 repatriation movement, the short life of the Armenian community of Kalamata came to an end. But this isn’t absolutely true. In the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a new wave of emigration began from former Soviet Armenia to western countries. This led to the creation of a new, small Armenian community in Kalamata. The local Armenians use the Greek Saint Nigoghayos Church for services and have an active community life.

- [1] “Το χθεσινό προσφυγικό συλλαλητήριο, το επιδοθέν ψήφισμα” [“Yesterday’s Protest Staged by the Refugees and their Note of Demands”], Σημαία Καλαμών [Flag of Kalamata], 9 Jan. 1923, Kalamata.

- [2] Vartan Vartanian, “Kalamata,” Hounahay Darekirk [Greek-Armenian Yearbook], 1927, year one, Nor Or Press, Athens, pp. 380-381.

- [3] Sekim, “The Armenian Community of Kalamata,” Nor Or [New Day], 22 Nov. 1934, Athens; a reporter, “The Armenian Community of Kalamata,” Nor Or, 26 Jul. 1936, Athens.

- [4] Vartan Vartanian, “Kalamata.”

- [5] A reporter, “The Armenian Community of Kalamata”; Sekim, “The Armenian Community of Kalamata.”

- [6] A resident of Parapighmata, “Educational Life in Kalamata-Parapighmata,” Nor Or, 19 Oct. 1934, Athens.

- [7] A local, “Educational Life in Kalamata-Parapighmata,” Nor Or, 8 Oct. 1930, Athens.

- [8] A spectator, “Echoes from Kalamata,” Nor Or, 8 Oct. 1930, Athens.

- [9] A reporter, “Vartanants in Kalamata-Parapighmata,” Nor Or, 12 Mar. 1930.

- [10] A reporter, “Jirayr,” Nor Or, 1 Apr. 1931, Athens.

- [11] Archives of the Armenian Prelacy of Greece, letter from the board of trustees of the Aramian School, 18 Dec. 1933, Kalamata; Sekim, “The Armenian Community of Kalamata.”

- [12] Archives of the Armenian Prelacy of Greece, results of census conducted in 1939 – Kalamata.

- [13] A reporter, “The Armenian Community of Kalamata,” Nor Or, 28 Dec. 1936, Athens; a reporter, “Armenian Life in Kalamata-Parapighmata,” Nor Or, 17 Oct. 1930, Athens; a resident of Parapighmata, Nor Or, 2 Sep. 1931, Athens.

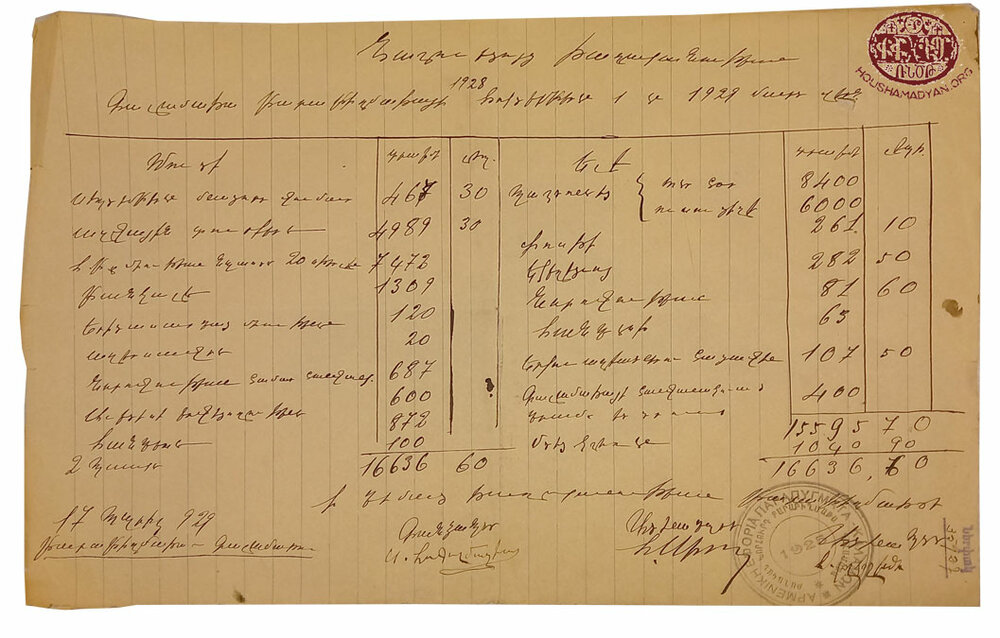

- [14] “Budget of the Board of Trustees of the National Aramian School, 1936-1937 School Year,” 17 Dec. 1936.

- [15] Vosgemadyan Haygagan Parekordzagan Unthanour Miyoutyan, 1906-1931 [Golden Book of the Armenian General Benevolent Union, 1906-1931], volume 1, Paris, pp. 240-241.

- [16] A reporter, “Mourning Ceremonies in Kalamata,”, Sevan (tridaily newspaper), 15 Mar. 1934, year 2, number 87, Athens; “The Work of the Armenian Rescue Committee in Kalamata,” Ararat newspaper, year 1, number 2, 23 Jan. 1925, Athens.

- [17] Sekim, “The Armenian Community of Kalamata.”

- [18] S., “The Armenian Community of Kalamata is Divided,” Nor Or, 4 Sep. 1934, Athens.

- [19] A reporter, “ARF Day Events – in Kalamata,” 12 Oct. 1928, Athens.

- [20] A reporter, “Mourning Ceremonies in Kalamata,” Sevan (tridaily newspaper), year 2, number 87, 15 Mar. 1934, Athens.

- [21] A reporter, “News from Kalamata,” Nor Or, 16 Feb. 1924, Athens.

- [22] A resident of Parapighmata, “Echoes from Kalamata”; Sekim, “The Armenian Community of Kalamata.”

- [23] P. Khachigian, “Armenian Life in Kalamata-Parapighmata,” Nor Sharjoum [New Movement], 18 Oct. 1931, year 2, number 35 (80), Athens.

- [24] A sports lover, “The Ararat football team of Kalamata-Parapighmata,” Nor Or, 27 Feb. 1930, Athens.

- [25] Interview with Yeranouhi Mgrdichian, August 2000, Athens.

- [26] Nor Gyank, 18 Jul. 1946, year 2, number 402, Athens.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] Letter from the Kalamata neighborhood council and the AGBU Kalamata chapter to the Central National Council in Athens, 6 Mar. 1943, Kalamata.

- [29] Ibid.

- [30] These included the Sarakian, Tavitian, Sharabkhanian, Chinarian, and Khasmanian families.

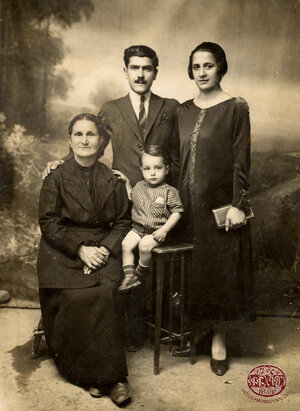

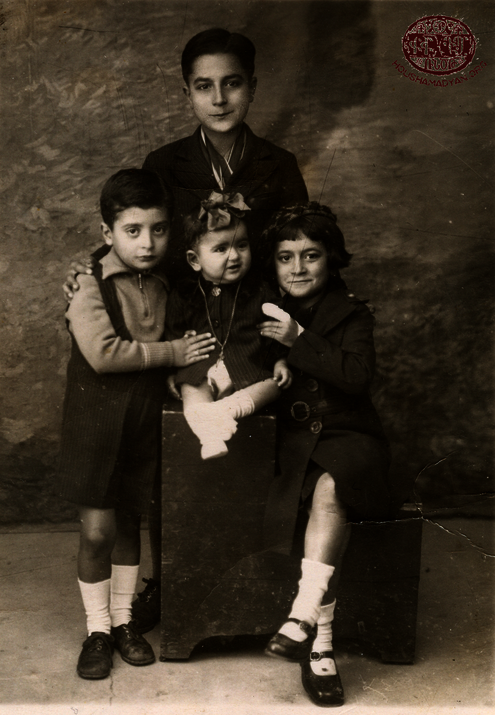

Kalamata, the Chinarian family. Front row, left to right: Mendouhi, Meline Chinarian, an unidentified woman with a baby in her lap (also unidentified), an unidentified woman, Haygaram Chinarian, and an unidentified woman. Standing, left to right: Adrine Chinarian, Haroutyun Chinarian, Zakar Chinarian, Hovhannes Chinarian, and Gadarine Chinarian (Source: Azad Garabedian (nee Chinarian)).

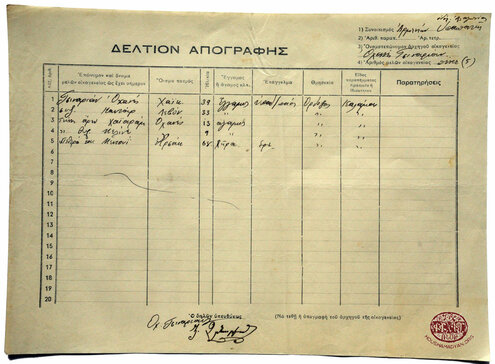

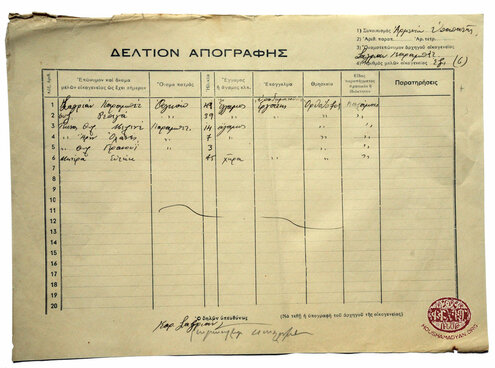

The results from Kalamata of the 1939 census conducted by the Armenian Prelacy of Greece. Each sheet represents a separate family and lists, in Greek, the family’s surname, the first name and age of each member, as well as each family member’s occupation/profession. The first sheet belongs to the Chinarian family. The head of the household is listed as Ohannes Chinarian, 39 years old, and a cobbler. The second sheet belongs to the Saghrian family. The head of the household was Garabed Saghrian, 49 years old, and a cobbler (Source: Archives of the Armenian Prelacy of Greece).

Kalamata, the Chinarian family. Front row, left to right: Haroutyun Chinarian (seated), Sarkis Chinarian (standing), unidentified individual (seated), Haygaram Chinarian, Mendouhi (seated), Meline Chinarian, and Hovhannes Chinarian. Standing, left to right: Adrine Chinarian, Zakar Chinarian, and Gadarine Chinarian (Source: Azad Garabedian (nee Chinarian)).