Avedian collection - Montreal

05/10/23 (Last modified 05/10/23) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

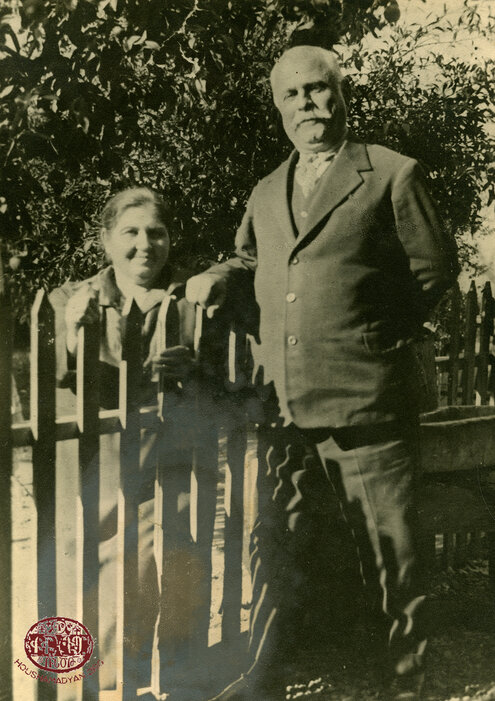

The oldest ancestor of the Avedian family who appears in records and is remembered by his descendants is Haroutyun Avedian, much better known as Avedoghlu Artin. According to the family's oral history, the Avedians were descendants of princes who ruled over the fort of Vahga in Cilicia. Haroutyun Avedian was born in the mid-1800s, lived in Adana, and had a reputation as a brave and selfless youth. In those years, the journey that Armenian pilgrims undertook from Sis/Adana to Jerusalem was fraught with dangers, as the road teemed with bandits who specifically targeted pilgrims’ caravans. Avedoghlu Artin was in high demand as a guard to escort the caravans and to ensure their safe passage. Riding his horse and armed with his rifle, he would accompany the caravans that set out around Easter. Throughout his career, he had been forced into many armed engagements with bandits.

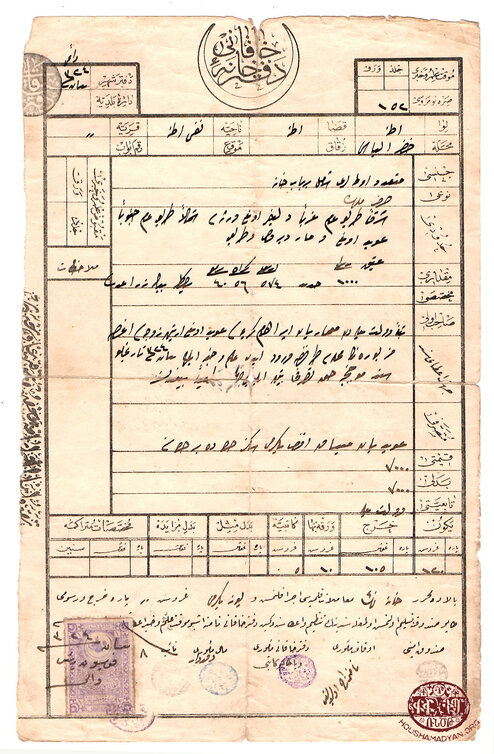

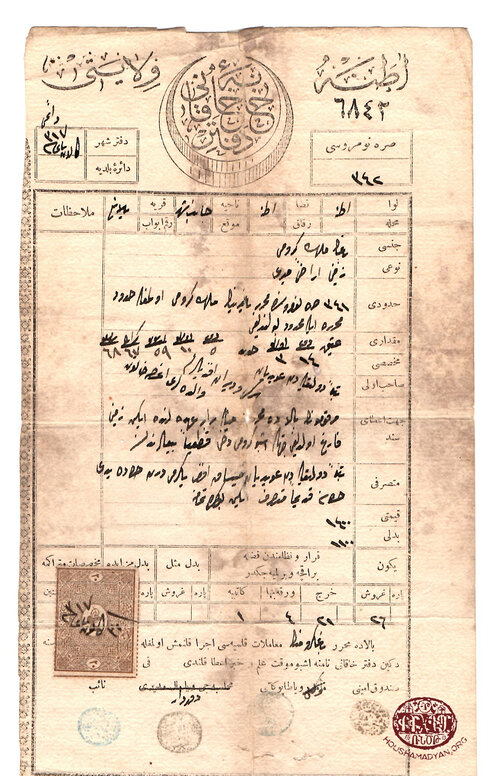

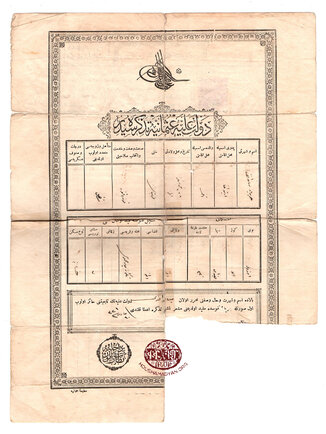

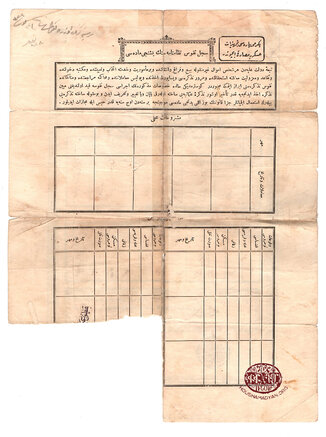

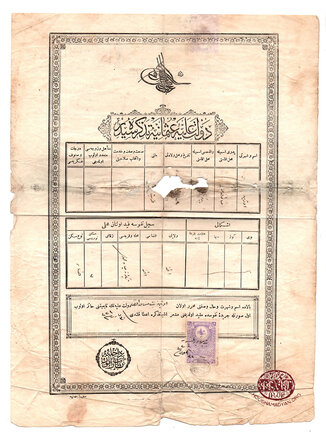

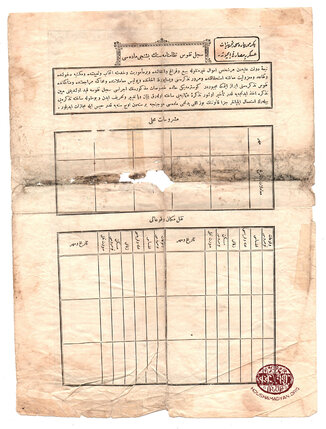

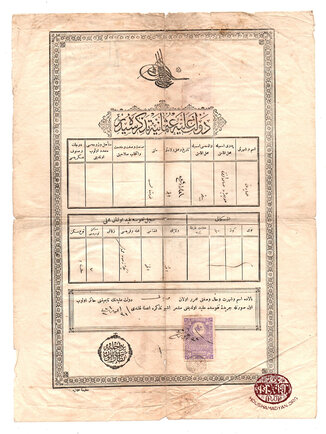

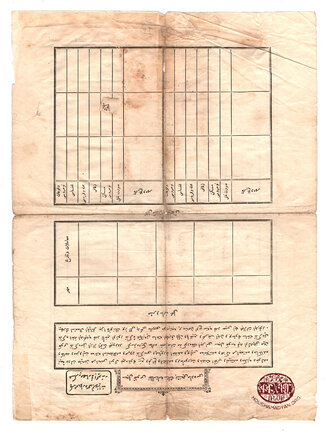

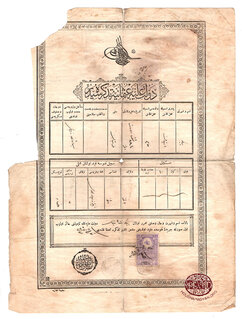

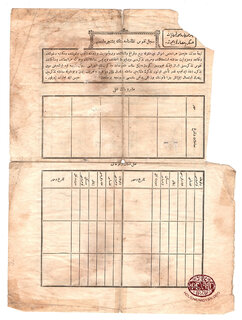

Avedoghlu Artin was also a property owner. He owned 15 plots of agricultural land in Anavarza/Anarzapa, as evidenced by the property deeds that are kept to this day by the family. In a letter dated June 9, 1919, and addressed to Capitaine Taillardat, the French governor of the province of Sis/Kozan, Avedoghlu Artin’s sons (Misak, Sarkis, and Diran), requested that the governor intervene to fairly resolve disputes regarding the legal ownership of these estates. From the letter, we learn that these lands had become the property of others, and the brothers claimed that the transfer of ownership had been illegal.

In Adana, Avedoghlu Artin married Yeghisapet Meymarian (Aghsa Hanum), daughter of Meymar Oghlou Apraham Agha. The Meymarians were one of the prominent and wealthy Armenian families of Adana. In her memoirs, Sayeni Balian wrote that the household included a hired French tutor, who had been specially brought from Marseille to Adana. Also according to Sayeni Balian, the Meymarians were pioneers in introducing European customs and fashions to Adana. For example, they were the first family in the city to dine seated around a dinner table. The local custom was to dine sitting cross-legged on the floor, around a low table (koursi). It was also said that Yeghisapet (or Avedoghlu Agha Hanum, as she was called), was one of the first women to wear European clothing in the city. The women of Adana usually wore shalvars, with a kirma scarf wrapped several times around their waists. When Yeghisapet came out into the streets for the first time wearing her fashionable attire, the children began circling around her and chanting:

Madama, madama,

Heç benzemez adama.

[Madam, madam,

Doesn’t look anything like a man.]

Returning home, Yeghisapet vowed to never dress like that again. But a short time later, the “alafranka” style, as it was known, became the newest trend embraced by upper-class women in Adana.

Yeghisapet had a brother called Bedros, who died from tuberculosis at a young age.

In Adana, Artin Effendi acted as the representative of the Persian consul. The Persian government was exceedingly satisfied with his work, and as a token of its appreciation, presented him with a silk, gold-threaded collar and cuffs. But a more symbolic reward was the valuable hookah (nargile) that he received, which quickly became well-known within his familial and social circles. People would visit him just to see this hookah, which had a height of one meter and a gilded bowl. In 1909, during the massacres of Adana, this hookah was among the many items that were stolen from the family.

Yeghisapet and Artin initially had seven or eight children, all of whom died immediately after birth. Finally, they had two more children who survived. One was Abdulmesih, and the other was Sayeni. The choice of these names is notable. As a devout Christian family, the Avedians would surely have preferred biblical names for their children. A unique family anecdote explains the selection of these two names.

The well-to-do Armenians of Adana often spent the summer holidays in an area of the countryside called Guvleg Yaylassu, where the locals were native Arab Alawites (fellahs). One of these fellahs, a woman, was visited in a dream by an elderly man, who relayed the following message to her: “Aghsa Hanum will have a son and a daughter. They must be named Abdulmesih and Sayeni. They must be taken on a pilgrimage to the monastery of Saint Garabed, the sultan of Moush. If these instructions are heeded, the children will survive.” The fellah woman had this dream three times. Finally, she found Aghsa Hanum and told her about it. Aghsa Hanum, overjoyed, showered the fellah woman with gifts.

Thereafter, Abdulmesih, Sayeni, and two other sons, Sarkis and Diran, were born one after the other, and all of them survived infancy.

In her memoirs, Sayeni Balian wrote that the namesakes of Abdulmesih and Sayeni were heroes from traditional Christian stories. They were siblings, and among the first Christians in Judea. But they were persecuted for their faith and killed. At the site of their murder, a spring appeared, which became a pilgrimage site.

The first of the fellah woman’s instructions, relating to the children’s names, had been followed. But the second instruction, that of going on a pilgrimage to Saint Garabed, could not be obeyed. The journey was too dangerous. Instead, the family went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Aghsa Hanum was greatly shaken by this failure. In later years, she blamed this decision for the ills and misfortunes that befell the family.

Aghsa’s daughter retained the name Sayeni for the rest of her life. But her brother, Abdulmesih, changed his name to Misak. His birth overjoyed not only his parents, but the entire circle of the family’s relations and friends. Among these friends was Manoug Bey. On the occasion of Abdulmesih’s birth, he gifted the family a brooch encrusted with emeralds, which the family always called elmas chichek (diamond flower). Despite the deportations, massacres, and violence that the family experienced, they were always able to hold on to this elmas chichek. To this day, it is in the possession of the family’s descendants.

At the age of 16, Sayeni contracted tuberculosis and died. Artin Agha wrote a poem in her memory, which he often recited:

Hey, güzeller serfirazı mahtabanım çocuk

Sen cefakârın elinden büküldü belim çocuk.

Hey vah seni geç bulup tez yitiren anne babaya…

Hey, felek çarkın kırılsın bu bana nispet midir?

Beni güldürmedin, güldürme bırak ömrüm viran olsun…

[Hey, my resplendent, my moon of a child

He who brought you pain broke my back, my child.

Woe to the parents who found you so late, yet lost you so soon,

O, fate, may your wheel be broken, was this evil meant for me?

You never brought me joy; don’t bring me joy, may I live in ruins…]

Misak Avedian (1862-1941), after receiving his early education in Adana, was sent to Constantinople, where he attended and graduated from the Central School. Sarkis and Diran attended the Apkarian School of Adana. Misak became an engineer/architect. We do not know which university he graduated from. One possibility is that after graduating from the Central School, he studied engineering at the State University in Constantinople.

Misak Avedian married Rebecca Avedian (nee Arabian), and the couple had four children: Haroutyun (born in 1902), Eugenie (born in 1904), Sayeni (born in 1909), and Sion (born in 1913). Rebecca’s father’s name was Stepan, and her mother’s name was Khanum.

In April 1909, when the first round of massacres that targeted the Armenians of Adana began, the Avedians and their neighbors and relations, the Meymarians, found safety in the Jesuit School located across the street from their homes. They remained there until the Ottoman army intervened and reestablished order. Several relatives of the Avedians were killed in this bout of violence, including Soghomon Arabian (the brother of Rebecca, Misak Avedian’s wife); Sdepan Arabian, Rebecca’s father; Nazaret Dakesian; Garabed Dombourian; Samuel Dombourian; and Martha Dombourian.

Then began the second round of anti-Armenian pogroms, in which the army directly participated. Prior to the outbreak of violence, the Avedian home was visited by a Turkish chavoush (sergeant) called Ahmed, who was a friend of Misak Effendi Avedian. He secretively communicated news of the planned massacres to the Avedian family, instructing them to immediately leave the Armenian neighborhood and the city. Ahmed was part of the Ottoman army detachment deployed to Adana. Armed as he was, he was able to escort the family out of the neighborhood and all the way to the train station. There, the Avedians boarded a train that took them to Mersin, and from there they boarded a ship that took them to Egypt.

Misak had first made Ahmed’s acquaintance when he had been sent as an engineer to the mountainous areas of Adana. One day, he was approached by a beggar, who was Ahmed. Misak’s assistants had wished to drive him away, but Misak had intervened, had heard Ahmed’s story, and had hired him as his servant. The two had soon become friends, and lived alongside each other as “an older and younger brother.” Later, Misak returned to Adana, and lost touch with Ahmed, who enlisted in the Ottoman army and reached the rank of lieutenant. Upon reaching the city with the troops, he had risked his own life and commission by rushing to the aid of Misak and his family.

After staying in Egypt for some time, the Avedian family returned to Adana. Their house had been burned, alongside most of the Armenian neighborhood.

The Avedian family continued to live in Adana until 1915. The Genocide began, and the Armenian population of Adana received its deportation orders. It was during this period of terror, as the family prepared to leave, that a policeman appeared at the house and announced that he had orders to escort Misak Avedian somewhere. The family feared that Misak would be imprisoned and then sent to his death. Misak left with the officer, but it soon became clear that he had been summoned by Miralay Hamdi Bey.

Years earlier, Misak’s father, Artin Agha, had cultivated a friendship with Hamdi. One day, Hamdi had killed a man, and had been sentenced to death. Artin Agha had paid the sum of money required to save Hamdi from the death penalty. In the years of the Genocide, Hamdi had risen to a high rank in the military. He had decided to take the Avedian family under his protection. Misak informed Hamdi that he had sent a telegram to Ahmed Djemal Pasha, the commander of the Fourth Ottoman Army and the former vali (governor) of Adana, asking to be appointed head of the army’s military road construction unit. Hamdi replied that he would soon head to Aleppo, and that Misak could contact him there whenever he felt the need.

Djemal Pasha replied to Misak’s telegram, acceding to his request. And so, the family headed for Palestine. They accompanied the Armenian deportation caravan as far as Aleppo. A bodyguard escorted the family, and the Turkish flag waved from their chariot, to ensure that the Avedians would not be confused with the crowd of deportees.

They reached the concentration camp of Katma. Misak always had Djemal Pasha’s telegram on hand. This missive was a true lifeline for the family, as many of the deportees were sent from Katma right into Deir ez-Zur. Thanks to this telegram, the family only stayed in Katma for a short time, and soon reached Aleppo. There, they stayed at the Hotel Baron. But Turkish policemen were a constant threat. While on the one hand, Misak prepared to leave for Palestine, Turkish policemen constantly hounded and interrogated members of the family. Each time, it was Djemal Pasha’s telegram that saved them. But one policeman decided that this telegram was a forgery and ordered the arrest of the family. This was when Misak appealed to Miralay Hamdi Bey. The latter intervened immediately and organized the family’s journey to Jerusalem.

And so, after remaining in Aleppo for only eight days, the Avedians took the train to Damascus, and from there proceeded to Jerusalem, where they settled in the Saint James (Sourp Hagop) Monastery. During the years of war, Misak built trenches, bridges, and roads for the Ottoman army. He often hired Armenian deportees, who would thus receive proper rations and would be spared further deportation to other areas. Misak also employed his teenaged son, Haroutyun, as his assistant.

After the end of the First World War, the Avedian family returned to Adana. Their home in the city was unscathed, but their home in the vineyards had been destroyed and the trees had been cut down. Misak and Rebecca’s son, Haroutyun, remained in Jerusalem for some time. After the Armistice, he attended the Saint Joseph College in the city. In 1919, he returned to Adana, where he attended the Central Cilician School, and then the Apkarian School. Haroutyun was a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation’s youngsters’ wing, and later its youth wing.

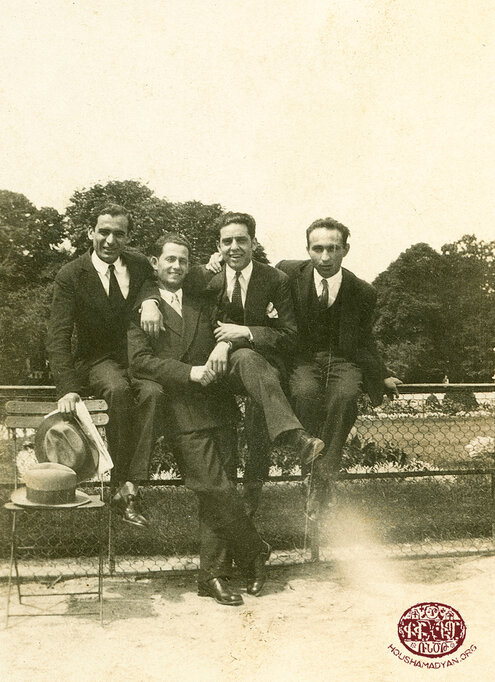

The Avedians continued living in Adana for a few more years, until the final exodus of Armenians from the city in 1921. In December of that year, the family left for Cyprus, where they settled in the city of Nicosia. Misak Melkonian was hired to work on the construction of the Melkonian School, and later became this institution’s provisioner. Haroutyun was a member of the Nicosia Committee of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. In 1926, he left for Paris, where he studied engineering and architecture at the École Spéciale des Travaux Publics. He graduated in 1931, and worked for several years in Paris as an engineer.

After living in Cyprus for seven years, the Avedians moved to Beirut. In 1934, Haroutyun also returned to Beirut from Paris. Among the buildings that he designed in Lebanon were the Jesuit College in Jamhour and the Holy Mother-of-God Church in Bikfaya. In 1937, he married Marie Gabrache. The couple had three children: Mirella, Astrid, and Diran. Haroutyun died in 1969.

Haroutyun’s sister, Eugenie Avedian (later Balian), had attended the Ashkhenian School in Adana, and later the city’s Hripsimyants School. Between 1922 and 1932, she worked as a teacher at the Melikian School of Nicosia, and later the Melkonian Institute. When the family move to Beirut, she resumed her career as a teacher, and taught at the Saint Nshan School from 1932 to 1935. She was a member of the Armenian Relief Cross, and for many years of the Women’s Committee of the Saint Nshan Church. She married Hayg Balian, and the couple had three children: Ardzvig, Anahid, and Alenoush. Eugenie died in 1981, in Algiers.

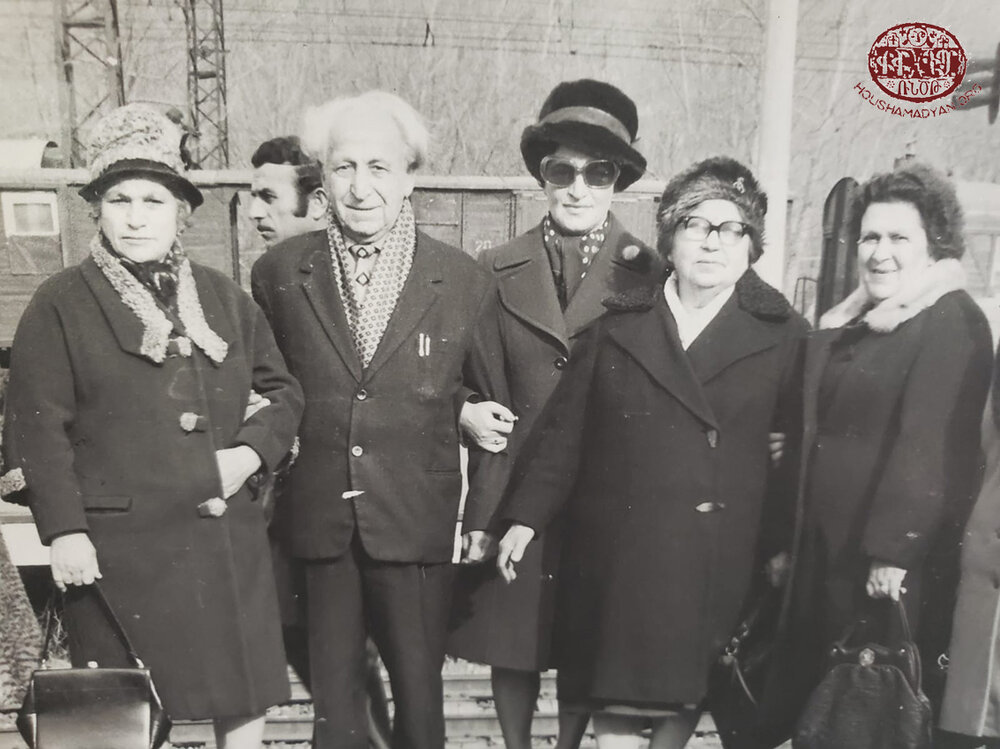

After coming to Beirut, Sayeni followed her sister’s example and began working as a teacher at the Saint Nshan School. In 1934, she married Melidos Balian. The couple had two sons, Vache and Zareh. In 1946, Sayeni and her family emigrated to Soviet Armenia and lived in Girovagan (present-day Vanatsor). In 1978, they received permission to leave the Soviet Union and emigrated to the United States, where they lived in the city of Los Angeles. Sayeni died in 2000.

Sion Avedian graduated from the National Melikian School in Nicosa, Cyprus. After moving to Beirut, Sion worked alongside his father. Thereafter, he joined his brother in Avedian & Brother Construction company. Sion eventually ran his own construction company. In April 1945, he married Fimi Bedrosian, and the couple had two children, Missak and Sylvana. Fimi died of an illness in December 1964. Sion married his second wife Emily Shirikjian in September 1966 in the Sourp Asdvadzadzin Church in Bikfaya. Sion’s brother designed the church and Sion built it. Sion and Emily had one son, Shahan. They moved from Beirut to the United States in March of 1977. Sion died in January 1988, and Emily passed away in August 1993.

Misak Avedian died in Beirut in 1940. His wife, Rebecca Avedian (nee Arabian), died in 1949.

Sources

- Sayeni Balian, Housher Stalinyan Orerits [Memoirs from the Days of Stalin], Los Angeles, 1988.

- Sayeni Balian, Avedian Kertasdani Houshakroutyunu [The Chronicle of the Avedian Clan] (unpulished).

- Puzant Yeghyayan (ed.), Adanayi Hayots Badmoutyun [History of Adana Armenians], Printing House of the Holy See of Cilicia, Antilias (Lebanon), 1970.

- Haourtyun Avedian (on the forty-day anniversary of his death), Aztag Newspaper, 17 January 1970, year 43, number 266 (11531), Beirut (Lebanon).

- Oral testimony of Diran Avedian (Montreal).