The Mateos Zarifian Archive – Beirut, Lebanon

Author: Nora Sarafian-Tashjian 11/12/19 (Last modified 23/12/19) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

Editor’s Note

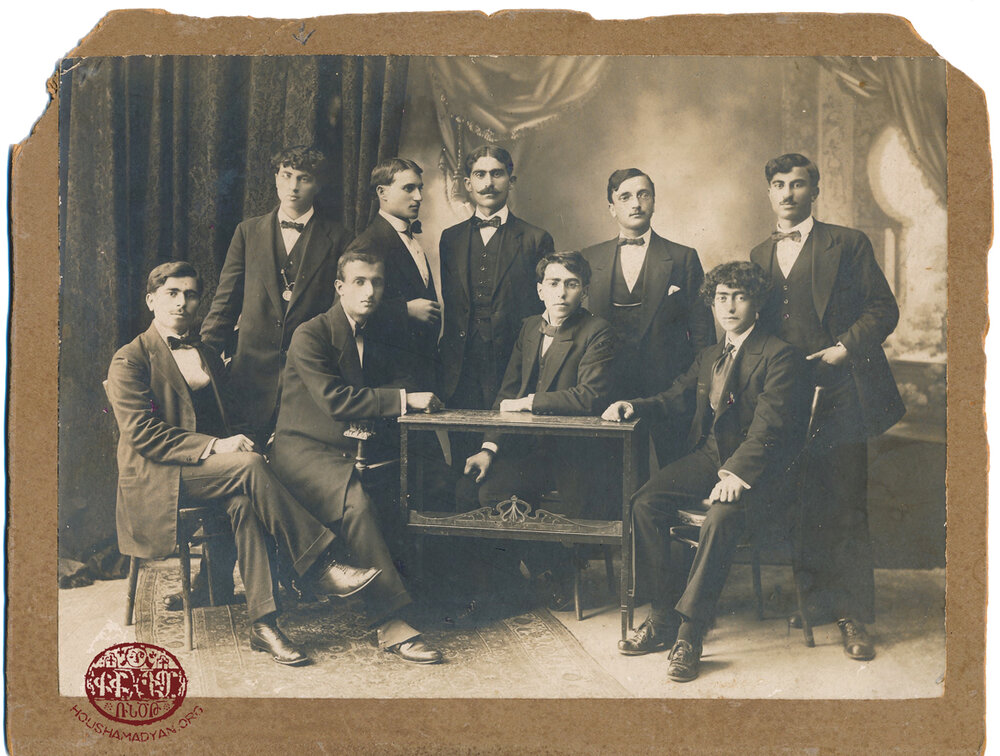

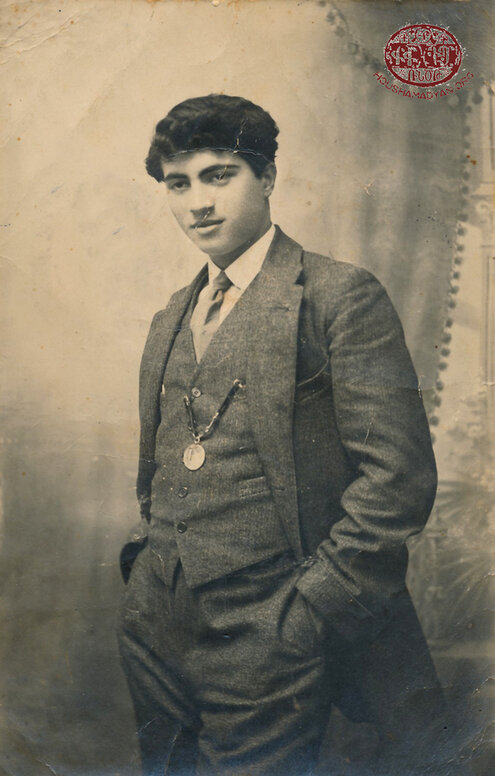

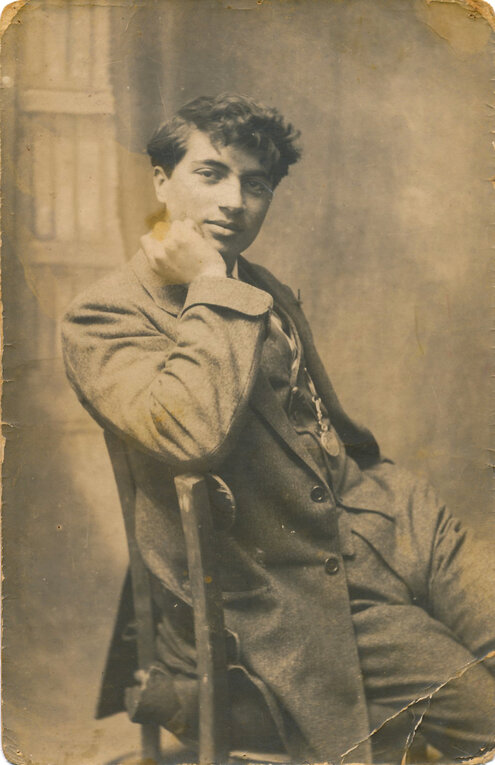

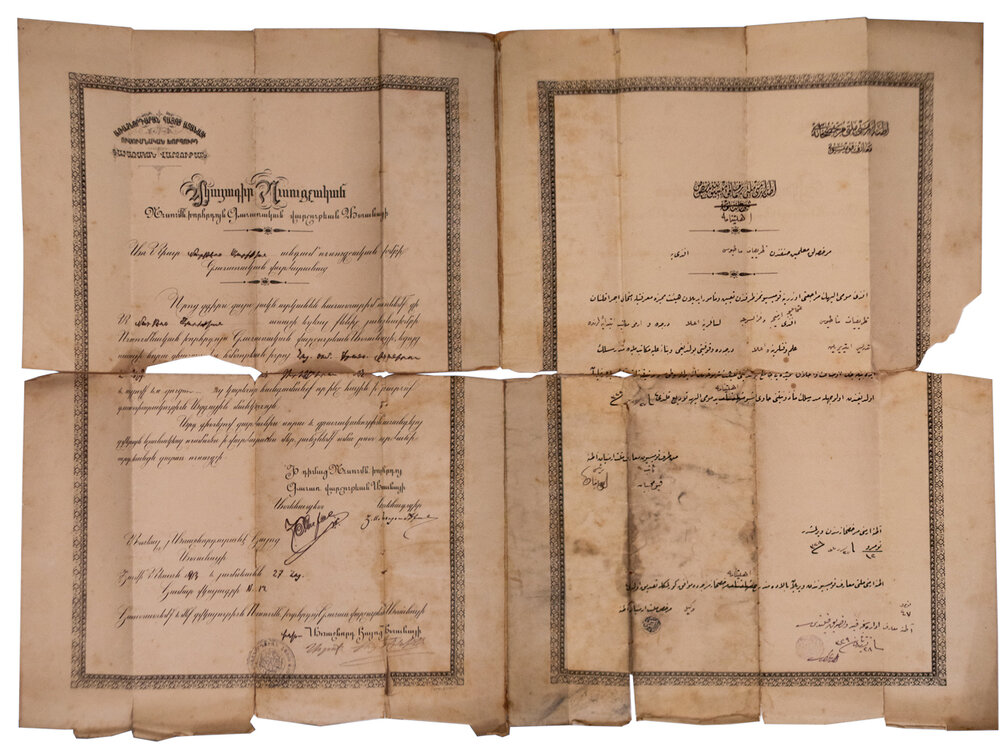

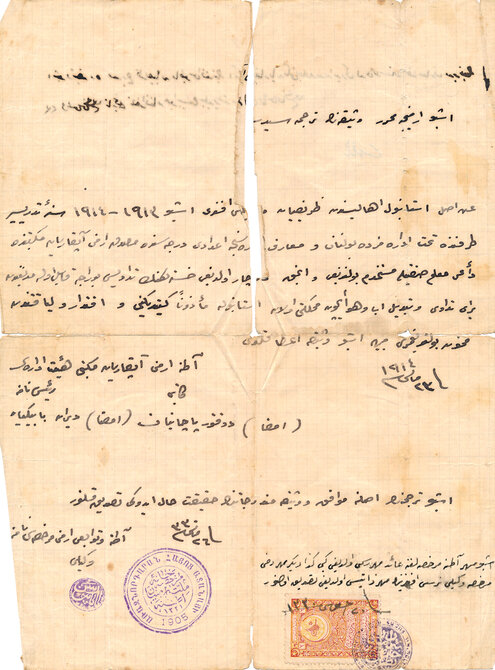

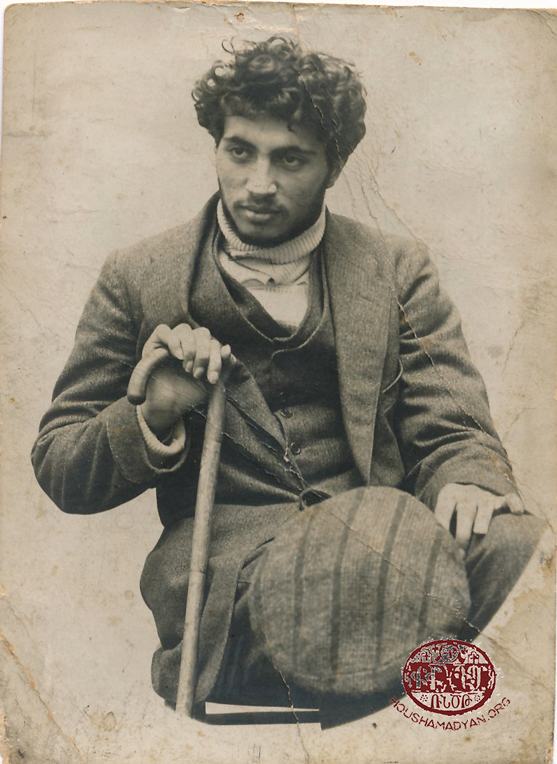

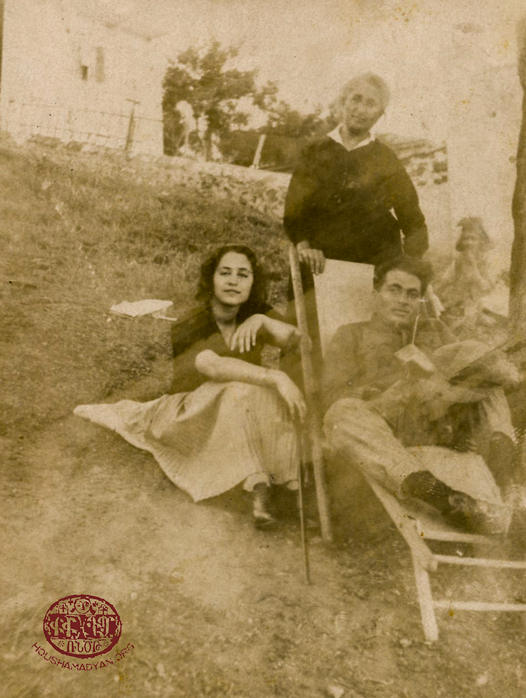

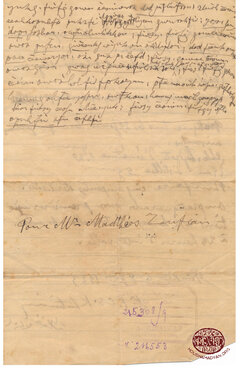

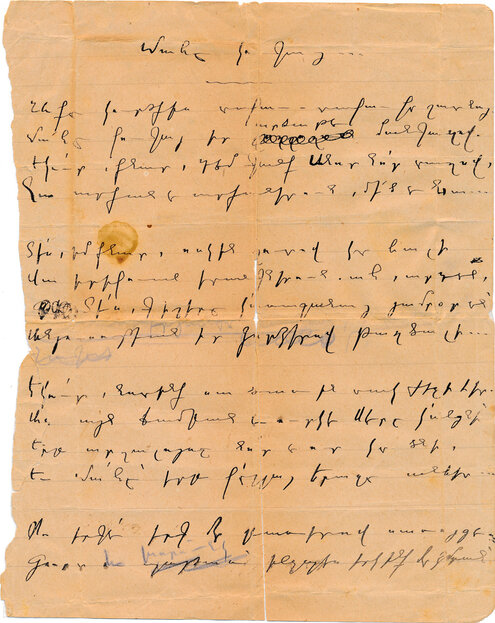

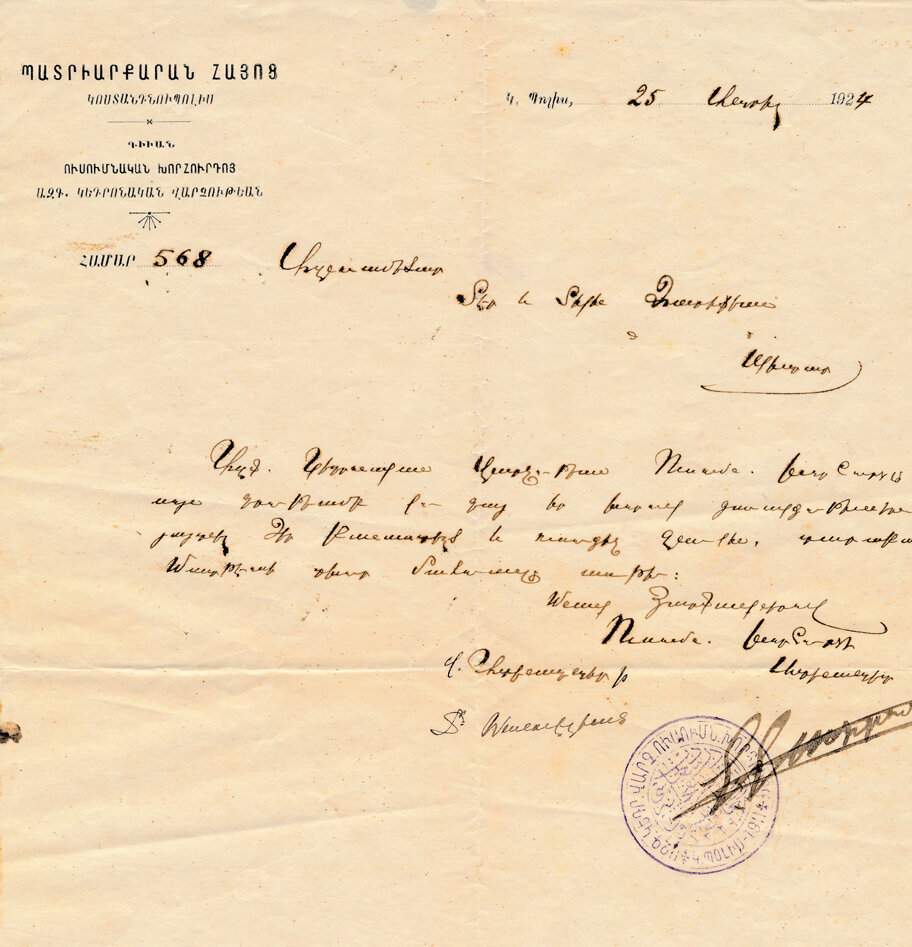

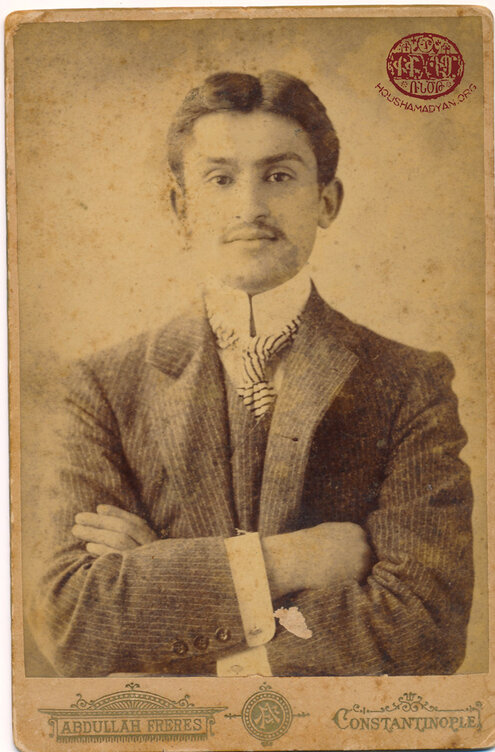

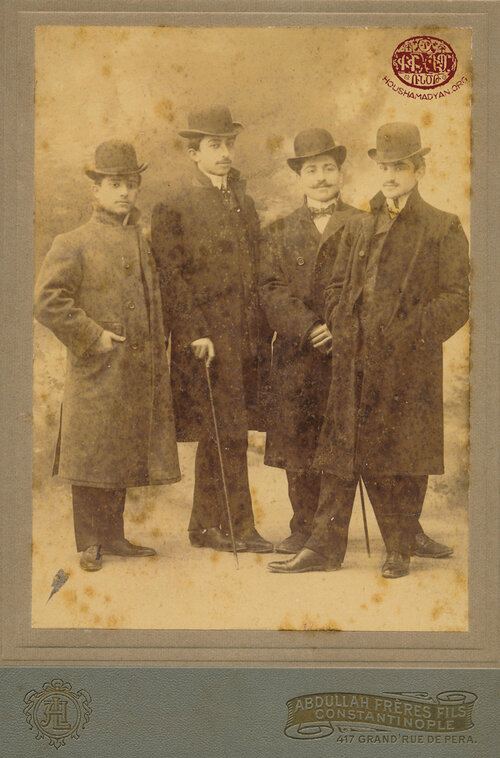

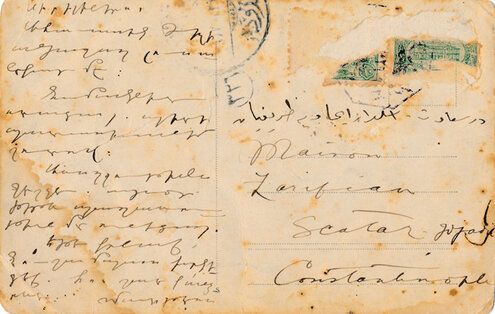

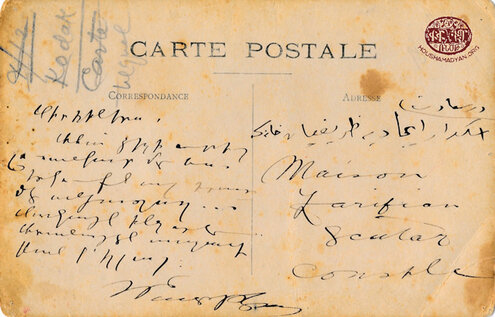

On this page, we present photographs, documents, and other memory items belonging to Mateos Zarifian and his family. Mateos Zarifian (1894-1924) was a poet who lived and worked in his hometown of Constantinople. All material presented on this page is the property of the Mateos Zarifian Archive, and was provided to us by the custodian of the archive, Sylvia Adjemian. It should be noted that these materials are a small portion of the entire archive. The Houshamadyan team wishes to express its special gratitude to Sylvia for her assistance. We also thank Hamazkayin association.

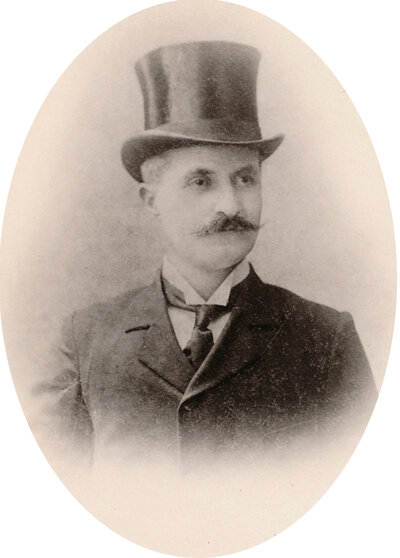

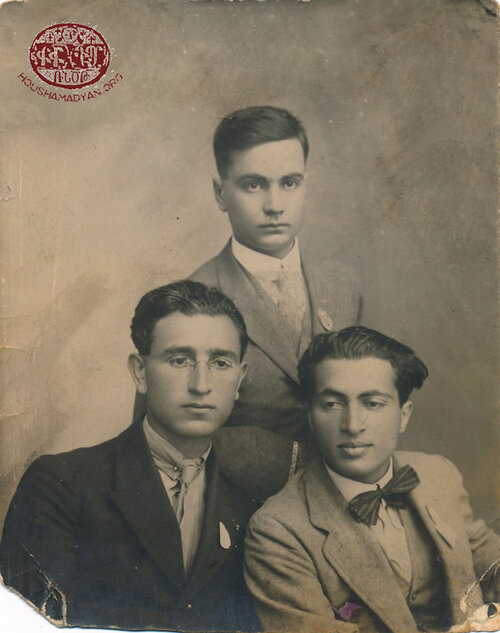

Mateos Zarifian, one of the gifted figures of Armenian lyric poetry, was born in Constantinople, in the Gedig Pasha neighborhood, in 1894. He spent most of his short life in the city’s Uskudar neighborhood.

He began his literary career in 1918 and died of tuberculosis in 1924.

Mateos’ life was full of contradictions, reflecting the contemporary experience of the Armenian nation. In quick succession, Ottoman Armenians experienced great hopes and disappointments; a cultural awakening and catastrophes; war, migration and deportations; and the excitement of the Armistice.

The fourth child of Dadjad and Hripsime Zarifian, Mateos Zarifian spent his childhood and youth in beautiful Uskudar/Scutari, in the lap of nature. He came to know death early in his life, when he lost his older brother, Vahakn. The memory of his brother, taken away in at such a young age, always remained vivid in his mind. He dedicated his first published volume of poems to Vahakn.

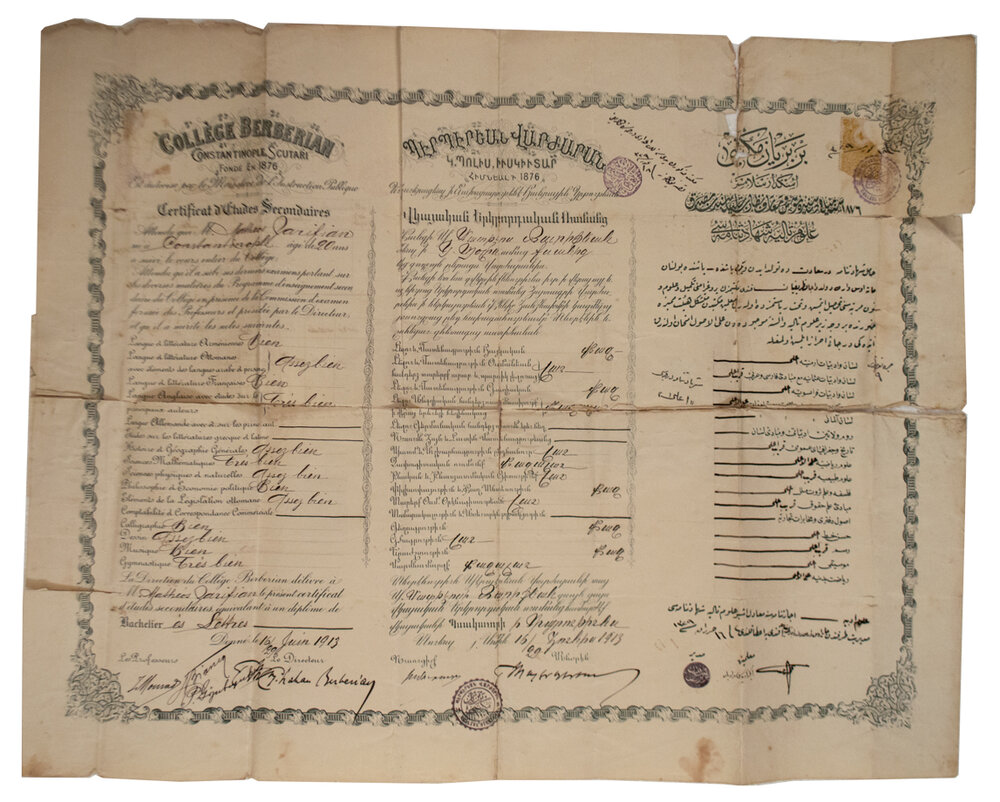

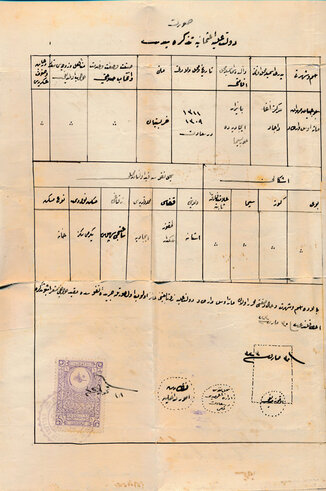

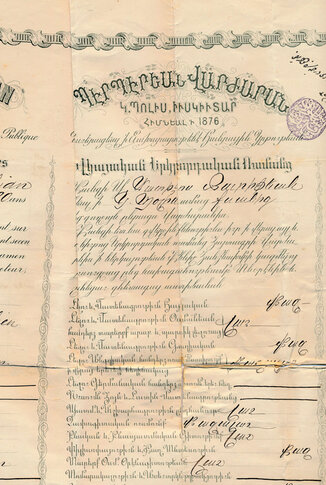

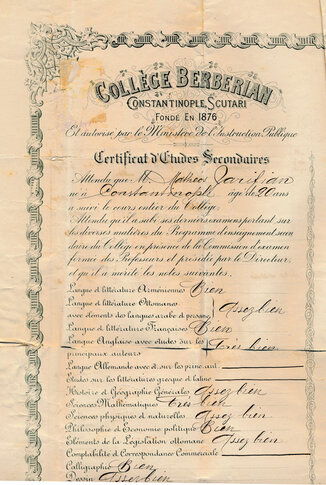

He received his primary education at the local parochial school of Uskudar before matriculating at the Berberian School (in the Kadıköy neighborhood). He then attended the American Bithynia College in the city of Bardizag and the Robert College (in Constantinople's Bebek neighborhood), before returning to the Berberian School, from which he graduated with the title of “Laureate in the Arts.”

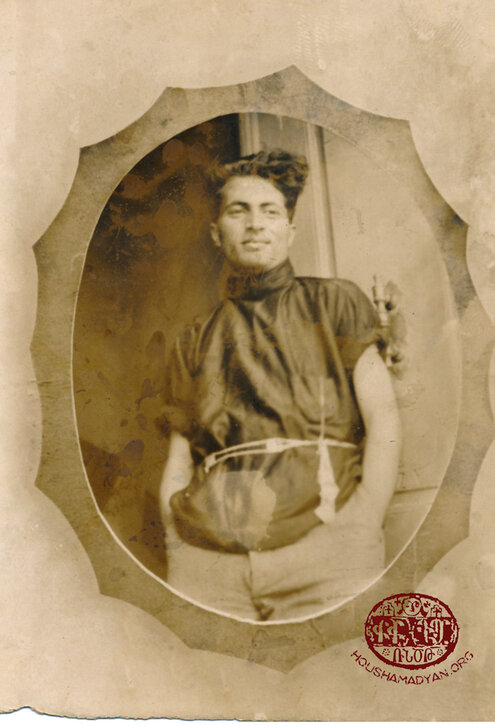

In those years, athletic and scouting movements were experiencing a period of great growth in Constantinople. Zarifian did not remain indifferent to these movements. Thanks to his great talents, he quickly became a well-known and well-liked name in the local athletic community, winning several prizes. This period also saw the growth of national-ideological movements within the Constantinople Armenian community. Zarifian, after graduating from the Berberian School, volunteered, in 1913, to leave for Cilicia and to help educate the new generation of Armenians there, namely by teaching English and physical education at the parochial school of Adana. However, before the end of that same school year, he was forced to leave Adana by an acute stomach ailment.

In the spring of 1914, he traveled to Lebanon to receive treatment for his stomach condition. A few months later, he returned to Constantinople and decided to pursue a career in medicine, pharmacy, or architecture, but the outbreak of the First World War thwarted these plans. He was conscripted into the Ottoman army as a non-commissioned officer. Unable to cope with the demands of military life, he resorted to desertion and mutinied against orders several times, which led to a military tribunal sentencing him to exile. Thanks to the intervention of several acquaintances, the sentence was commuted to imprisonment. Then, again thanks to outside intervention, he was able to secure a post in a military hospital as a “warden.”

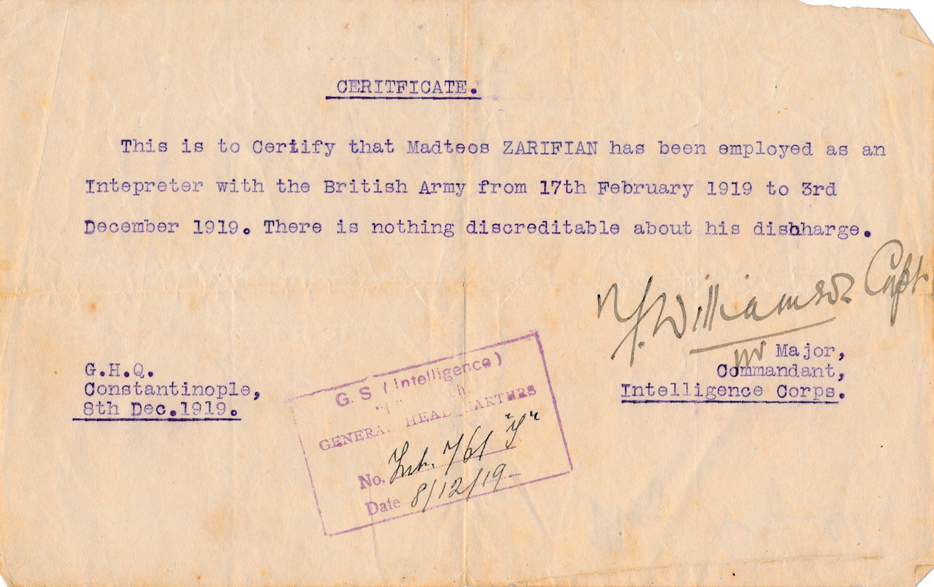

After the Armistice, Zarifian worked as a translator for the British occupying forces in Constantinople. In 1919, he was dispatched to the Armenian villages of Anatolia, alongside a British team, to assess the situation there and prepare the groundwork for the rounding up of Armenian orphans.

From the start of the school year in 1919 to the summer of 1921, he worked at the Berberian School in Constantinople, teaching English and physical education. He became a beloved poet of the school’s pupils and the wider community, as confirmed by Shahan Shahnour, a pupil at the Berberian School during Zarifian’s tenure. In a letter to Simon Vratsian, Shahnour wrote: “I preferred to stick to my circle, which consisted of Berberian students. This circle revolved around a poet, our poet, Mateos Zarifian” (Shahan Shahnour, “Dear Mr. Vratsian,” Pakin Monthly, Year 18, Number 4, 1979, Beirut).

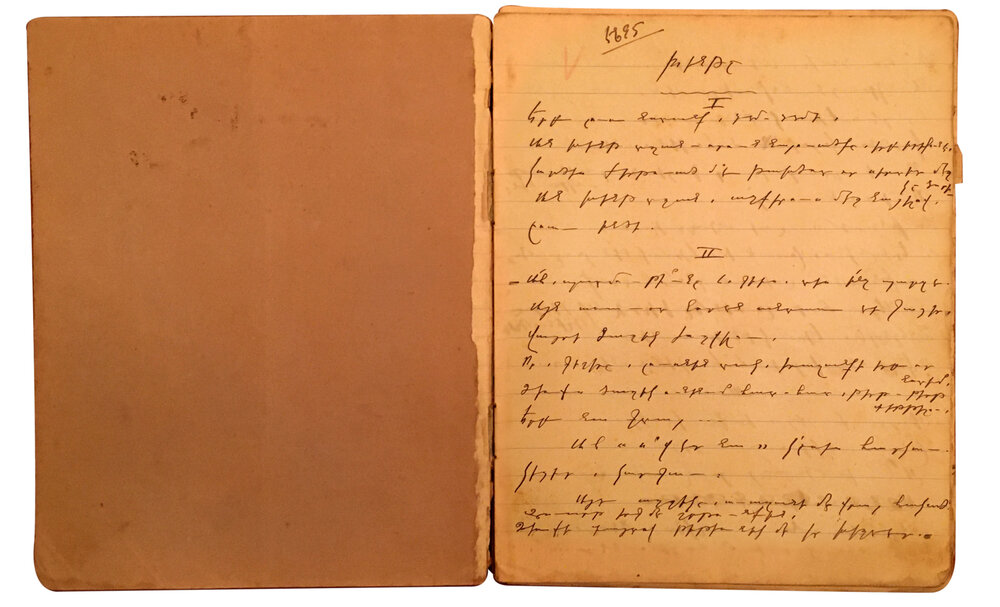

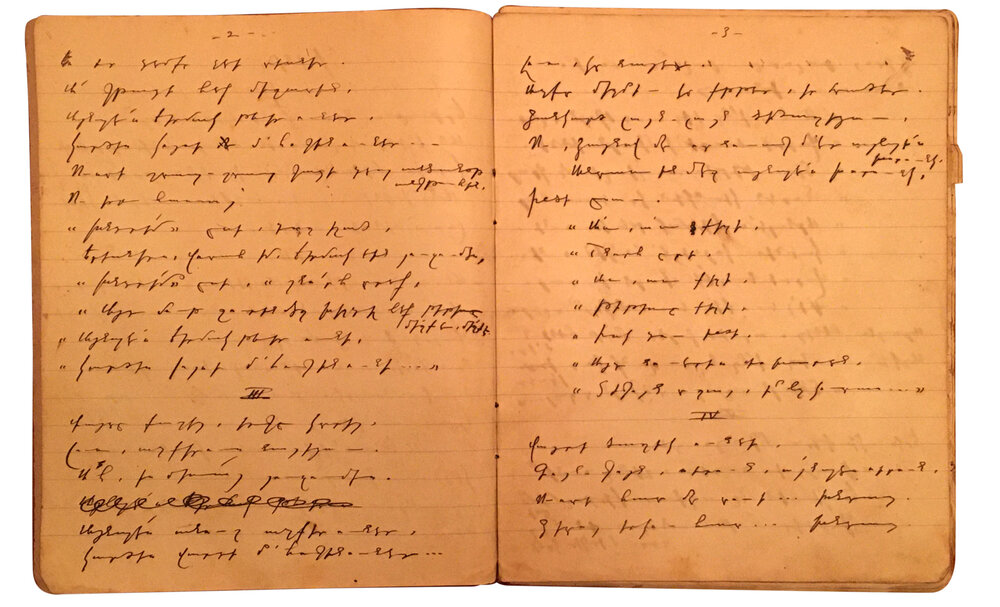

Zarifian’s illness very quickly consumed his young body, once brimming with such athletic vitality. This filled him with a great desire to end his own life, which in turn fueled his motivation to embrace creative work. Zarifian’s work first appeared in the Armenia media in 1918. The most productive years of his literary career were 1919 to 1923.

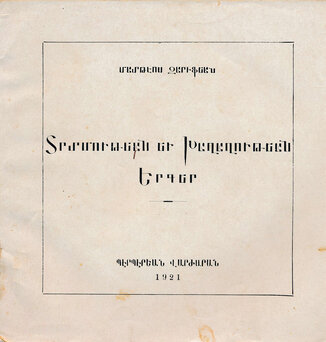

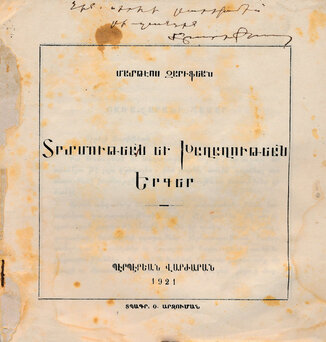

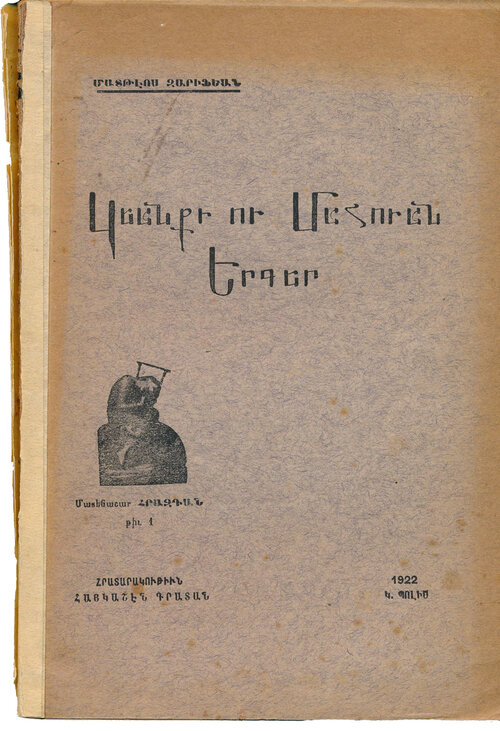

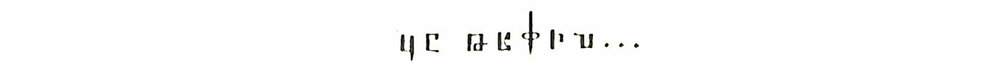

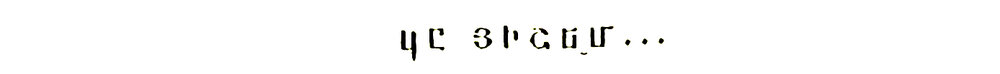

It was during these dark years of illness and suffering that Zarifian published two volumes of his verse, Drdmoutyan yev Khaghaghoutyan Yerker [Songs of Sorrow and Peace] and Gyanki yev Mahvan Yerker [Songs of Life and Death], in 1921 and 1922, respectively. These two volumes were enough to immortalize the name of this young poet who breathed his last on April 9, 1924, amidst the roses and fir trees of Constantinople's Big Island (Büyük Ada).

He was buried in the Armenian cemetery of Uskudar.

In 1956, an anthology of Zarifian’s poetry, titled Complete Works, was published in Beirut. It was edited by the poet’s sister, Siran Seza (Siran Zarifian-Kupelian), and Vahe Vahian. The anthology included the poems published in the two volumes released during Mateos’ lifetime, as well as previously unreleased poems, journal entries, correspondence, and selected prose.

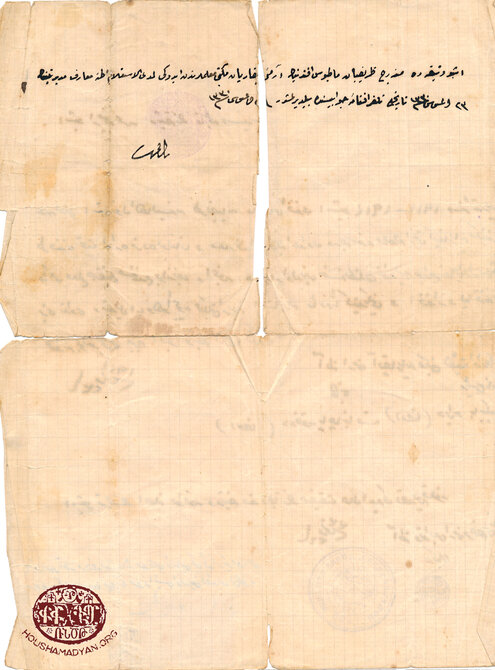

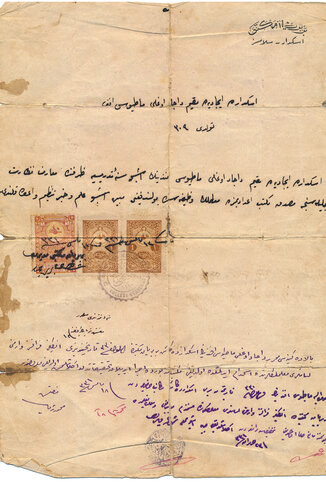

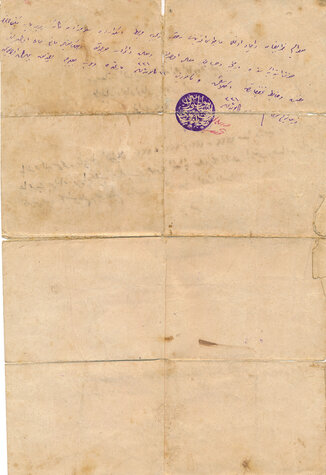

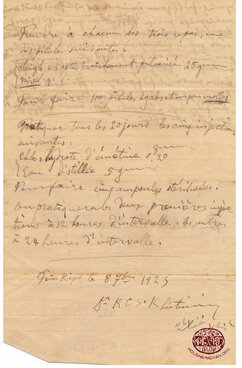

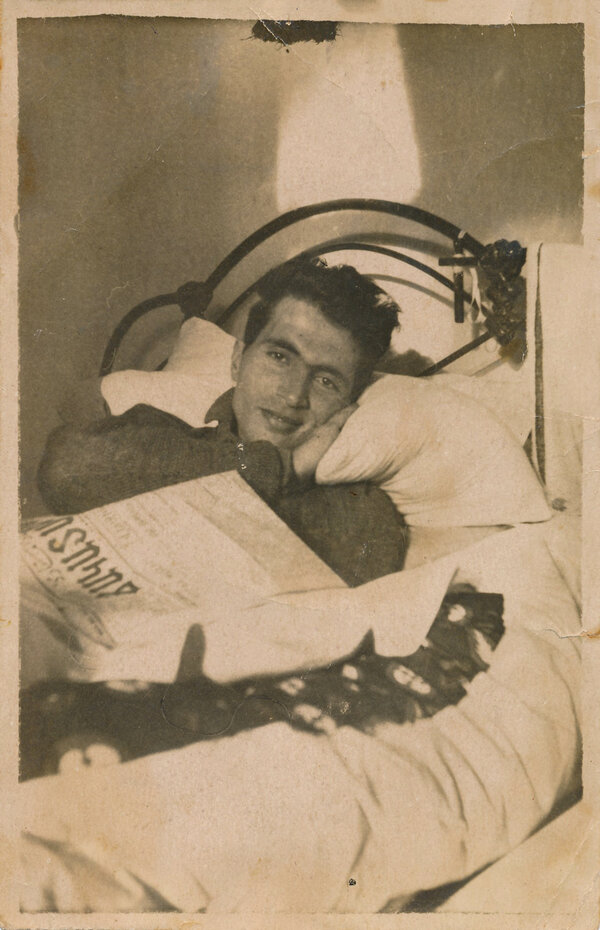

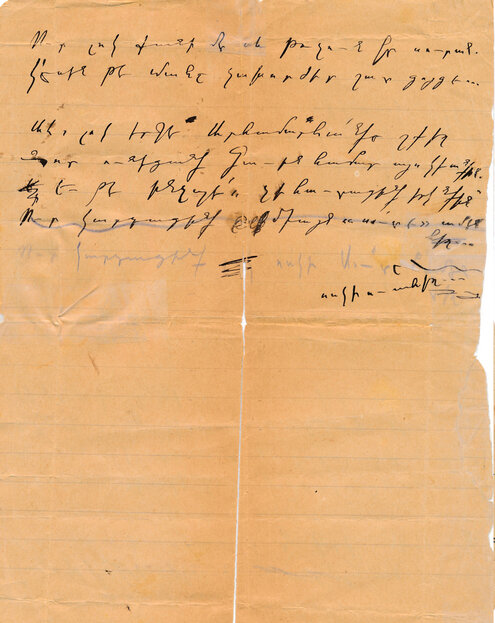

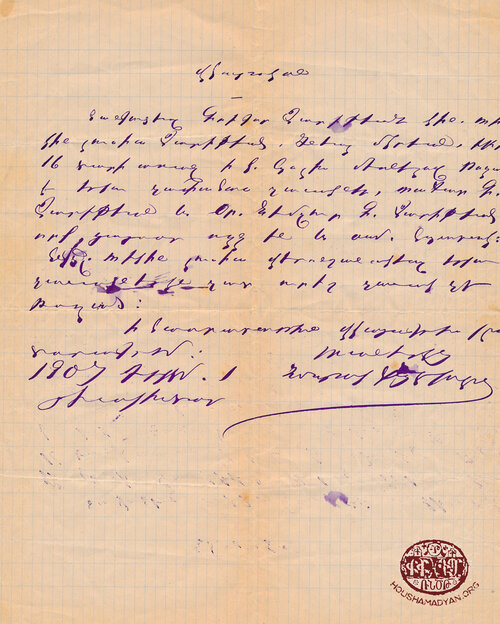

1) and 2) Medical prescriptions for Mateos Zarifian, bearing the signature of the Kelledjian Pharmacy.

3) More prescriptions for the ailing Mateos Zarifian. They are signed by Doctor Khintirian. They are dated May 17, 1921 (Pera) and 1923 (Prinkipo).

4) A prescription bearing the signature of the Minasian Pharmacy.

Mateos Zarifian’s bibliography:

- Drdmoutyan yev Khaghaghoutyan Yerker [Songs of Sorrow and Peace], Berberian School, O. Arzouman Press, Constantinople, 1921, 126 pages.

- Gyanki yev Mahvan Yerker [Songs of Life and Death], published by Haygashen Bookstore, Hraztan Anthology, F. Djarian Press, Constantinople, 1922, 115 pages.

- Endir Kertvatzner [Selected Verse], Sevan Press, Aleppo, 1946, 29 pages.

- Ampoghchagan Kordzer, Kertvadzner, Orakroutyan Echer, Namagner [Complete Works, Verse, Diary Pages, and Correspondence], Edited by Siran Seza and Vahe Vahian, Atlas Press, Beirut, 656 pages.

- Yerker [Songs], Armenian Publishing, Yerevan, 1965, 238 pages.

- Yerger [Complete Works] (Roupen Vorperian, Roupen Sevag, Vahan Tekeyan, Mateos Zarifian), Soviet Writer, Yerevan, 1981, 480 pages.

- Yerger [Complete Works], Edited by Apraham Alikian, Holy See of Cilicia Press, Antilias, 1990, 277 pages.

- Panasdeghdzoutyunner [Poems], Edited by Zoulal Kazandjian, Mekhitarine Order Press, Venice, 1994, 95 pages.

Additional Information about the Zarifian Family

The father of the family, Dadjad Zarifian (1860-1935), was a merchant by profession. He was married to Hripsime Zarifian (1864-1948).

The Zarifian children grew up in a home where artistic creativity was a way of life and was encouraged. The biographies of representatives of three different generations of the family show that even though they were temperamentally very different people, they were all endowed with great artistic and creative talents. Thanks to these talents, they made their mark and left a lasting legacy as authors, poets, and educators.

In 1924, after losing their second son (Mateos), the Zarifians moved to and settled down in Lebanon. There, the father continued to work as a merchant, while the daughters found work in their own fields of expertise.

Siran Seza (1903-1973), whose full name was Siran Zarifian-Kupelian, received a Master’s Degree in literature and journalism from Columbia University in New York. She then returned to Lebanon, where she continued practicing her profession. She contributed articles to the Hairenik monthly newspaper in Boston, the Aztarar weekly newspaper in Lebanon, and the magazine Nayiri. Among her published novels are Badneshe [The Rampart] and Meghavorouhin [The Guilty Woman]. Seza played an important role in shaping the image of the modern Armenian-Lebanese woman through the newspaper she published, titled Yeridasart Hayouhin [The Young Armenian Woman] (1932-1934 and 1947-1968).

Seza’s sister, Lucy Zarifian-Tosbath, was the director of the newspaper Ayk [Vineyard], published in Lebanon. Her husband, Dikran Tosbath, was a well-known politician and journalist, as well as the owner of Beirut’s Le Soir [The Evening] French-language newspaper. Lucy Zarifian-Tosbath made significant contributions to Lebanese journalism.

The daughter of Mateos Zarifian’s third sister, Berdjouhi Zarifian-Gulbenkian, was Yolande Gulbenkian-Adjemian. For many decades, she worked at the Hamazkayin Nshan Palandjian Djemaran. She was “Madame,” beloved and respected by her pupils. Between 1950 and 1975, she also contributed to Le Soir as an art critic. Her husband was the renowned caricaturist Diran Adjemian, and her daughter is Sylvia Adjemian, who lives in Lebanon and is one of the country’s most renowned art scholars.