Palandjian Collection – Piraeus, Greece

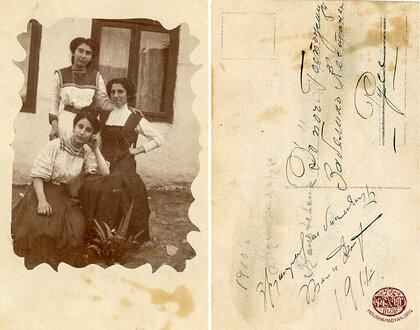

Author: Ani Apikian, 27/12/2023 (Last modified: 27/12/2023) - Translator: Simon Beugekian. This page was prepared collaboratively with the “Armenika” periodical of Athens.

This article chronicles the history of the Palandjian family. One of the most notable aspects of this history is the family’s vigorous involvement in economic and commercial life. The family founded the Palatex company in Amasya in the 1880s, and it continues to operate today. The company’s facilities are located west of the port of Piraeus, near the Agios Dionisios area (the site of the former Armenian refugee camp of Lipazma).

The article is divided into two sections. In the first section, we will explore the history of the Palandjian branch of the family, and in the second, the history of the Utudjian and Kestanian branches. Much of the information in the article was provided to us by Serko Palandjian in an interview. The second primary source we used is the Greek-language memoirs written by Serko’s mother, Adrine/Andrine-Takouhi Palandjian (nee Utudjian), κύκλος της ζωής [The Circle of Life]. The article provides a concise overview of the extensive family history detailed in this book.

The Palandjian Branch (Amasya, Smyrna, Piraeus)

Artin Palandjian was born in 1890, in the city of Amasya. He was the son of Hovhannes Palandjian and Lousaper Palandjian (nee Topalian). The couple had four more children: Hagop, Kourken, Serko, and Alice. Artin was the youngest son of the family. In Amasya, Hovhannes and Lousaper owned a weaving mill, which produced cotton fabric, sheets, tablecloths, and curtains. Weaving was the family occupation. When the boys came home from school, they would help their parents with their work. The mother would spin the yarn, the father would work the loom, and the children would fold and arrange the produced fabric.

In her book, Adrine-Takouhi Palandjian describes mass violence, massacres, and deportations in Amasya. The victims of these events included members of the Palandjian family. It is unclear when these events took place, but most probably, Adrine-Takouhi was describing the violence that the city witnessed during the 1915 Armenian Genocide. According to these memoirs, Artin predicted the looming danger and left Amasya to escape the catastrophe. The ensuing events are vividly described by Adrine: Turkish forces first rounded up the city’s Armenian residents, then deported them en masse. To save herself, Alice jumped into a river and drowned. Her mother, Lousaper, tried to save her daughter, but was shot dead by Turkish police officers. Lousaper’s husband, Hovhannes, was also killed during the deportations. Adrine/Andrine-Takouhi Palandjian’s memoirs state that Hovhannes and Lousaper’s other children, Hagop, Kourken, and Serko, also jumped into the river. Turkish officers opened fire on them, killing Kourken. Hagop survived the ordeal, while Serko was thought to have drowned. Many years later, in the 1960s, long after the family had given up hope of finding Serko, his granddaughter was discovered. She confirmed that her grandfather had survived the Genocide and had had two sons, Artin and Onnig; and a daughter, Alice.

Let us now return to Artin, Hovhannes and Lousaper’s youngest son. He had left his native Amasya just before the Genocide. He reached Izmir/Smyrna, where he tried to find a job, and was eventually hired by a sock factory, where he worked day and night. His employer, Yeprem Effendi, singled him out, often inviting him to his house, with the aim of eventually arranging a marriage between Artin and his daughter. Artin took the first chance to leave the factory and escape this situation. He continued living in Izmir. Using his savings, he purchased a second-hand loom, which he placed in one corner of his rented room. He weaved constantly, making socks for the Ottoman Army, gradually growing his business. One Sunday, on the coast of Izmir, Artin fortuitously bumped into his surviving brother, Hagop. We do not know the date of this reunion, but we know that Hagop told his brother the story of the family’s tribulations during the Genocide.

The two brothers, Hagop and Artin, began working together, weaving socks on the loom. Months later, they rented a larger house, bought three more looms, and expanded their business. Artin decided to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and earn the title of “hadji.” This decision was inspired by his and his brother’s survival of the Genocide. On this trip, Artin made the acquaintance of 15-year-old Yeranouhi Topalian, who also lived in Izmir, and the two fell in love. Upon his return to Izmir, Artin sought her out in the city, with the intention of marrying her. Yeranouhi was from Afyonkarahisar. She had lost all the members of her family during the Genocide. When the massacres started, by chance, ten-year-old Yeranouhi was in Smyrna with relatives to attend a wedding.

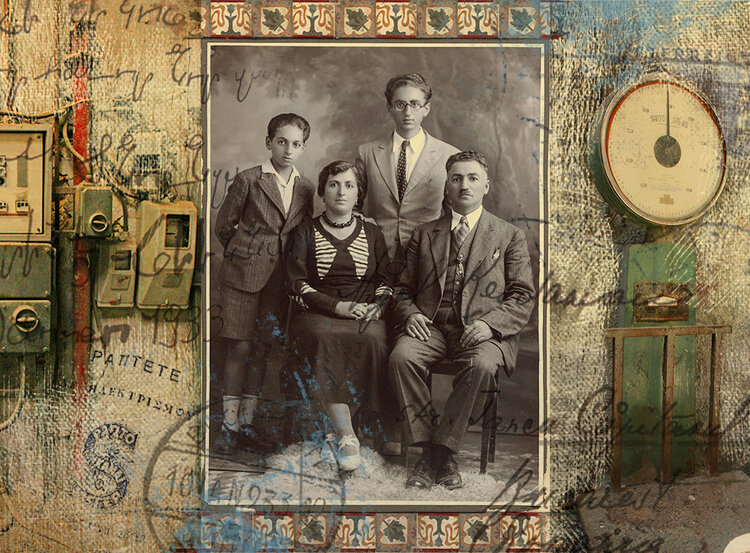

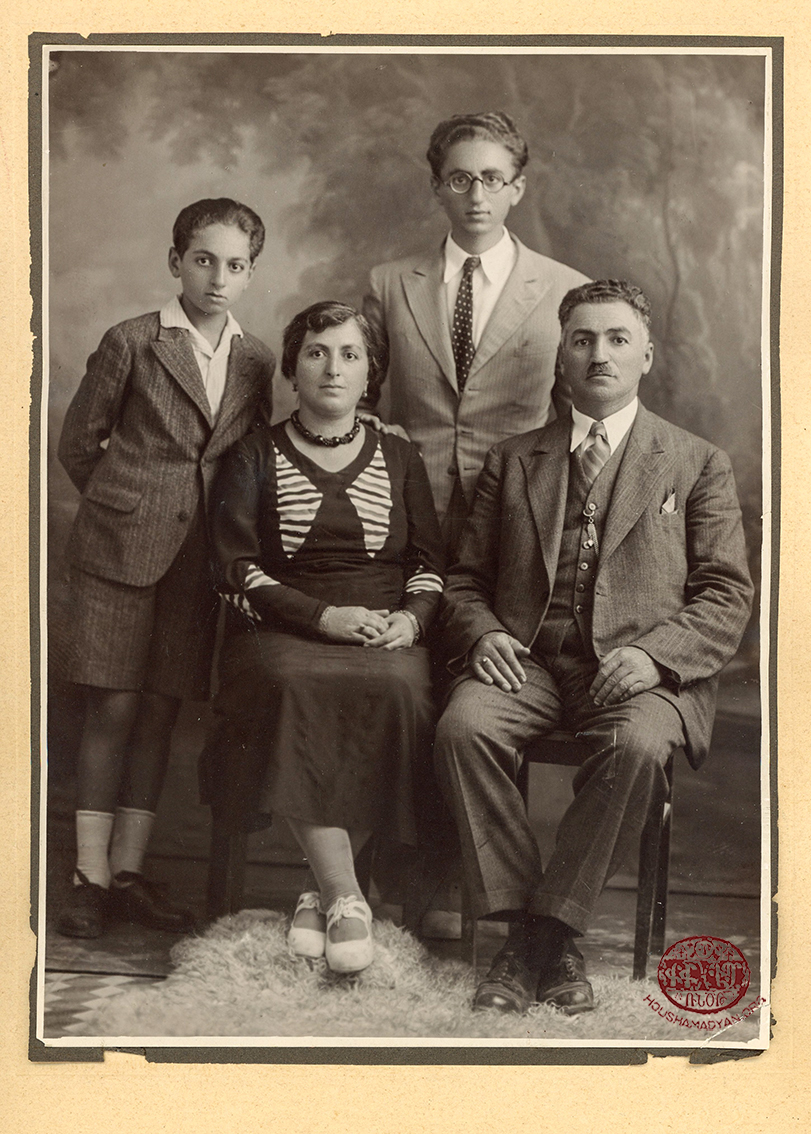

Artin and Yeranouhi married and had three sons, Onnig (born in 1915), Azad (born in 1919), and Serko; and one daughter, Alice. Serko and Alice died at a very young age. Yeranouhi had received basic education, and her main occupation was embroidery. Artin had taught himself reading and writing, was particularly skilled in mathematics, and had a keen mind. Artin and Yeranouhi lived and worked happily together. They spared no effort to advance the family business, importing looms from Italy and growing their wealth.

In 1922, on the eve of the Smyrna Catastrophe, Artin foresaw the danger. He and his brother, Hagop, decided to leave for Italy, where they had business acquaintances. Artin advised Yeranouhi to leave Smyrna at the first opportunity. And that’s what she did…

As the Smyrna Catastrophe unfolded, Yeranouhi fled home with four-year-old Onnig and two-year-old Azad, with all the family’s jewelry and cash hidden in her headscarf. They first hid in their Jewish neighbors’ home, then made their way to the port. Yeranouhi asked the captain of an Italian ship for passage for herself and her children. The captain, astonished by Yeranouhi’s fortitude, agreed, and even provided the family with a small cabin. The ship reached the port of Piraeus. From there, Yeranouhi and her sons traveled by train to the city of Larissa. Artin’s cousin, Hadji Aghavni, lived there. Three weeks later, Artin arrived from Italy. Thereafter, the whole family moved to Athens.

The Palandjian Weaving Company (Psyri, Piraeus)

When the family arrived in Athens, they rented a four-room home in the Psyri neighborhood. Artin and Yeranouhi decided to re-establish their weaving business. Artin built two wooden looms and placed them in one of the home’s rooms. The courtyard was used to boil the yarn, dye it, and to dry it on racks. Artin imported the dyes from Germany. The family business produced towels, tablecloths, sheets, and fabric, which were all sold easily in the market of central Athens. This was the origin of the Palandjian weaving company.

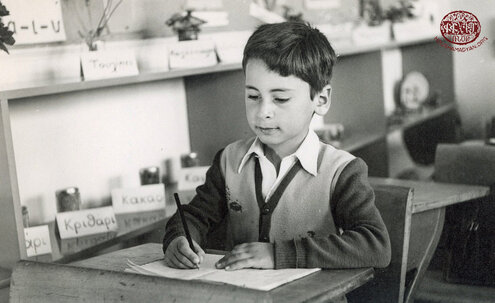

Onnig and Azad began attending the Leondios Greco-French school of Athens, which had a reputation as a modern and progressive educational institution.

A few years later, Artin Palandjian and his family moved to the Lipazmata refugee camp near the port of Piraeus, where they rented a larger and more suitable property for their business. By now, the number of looms that they operated had risen to 40. Most of the factory’s workers were Armenian women. However, the Greek authorities soon issued an edict requiring that workers of Greek descent make up the majority of the workforce in all factories. Yeranouhi would carry the products of the factory on her back to various destinations to sell them. It must be noted that at this time, textile weaving was not yet at an advanced stage of development in Greece, which created the perfect conditions for the Palandjians’ business to thrive and generate profits.

Around this time, Artin Palandjian invented an electric machine that operated the factory’s looms. This also allowed him to supply his home and factory with electricity for lighting. Artin had effectively created a small electrical supply system, from which his neighbors also benefited. Later, when Artin learned that the Power electrical company intended to supply the entire region of Adige with electrical power and was offering incentives for residents who contributed to this process, he benefited from this opportunity by erecting electrical poles all over his property.

The Balkania Public Baths (also known as Loutra Palandjian)

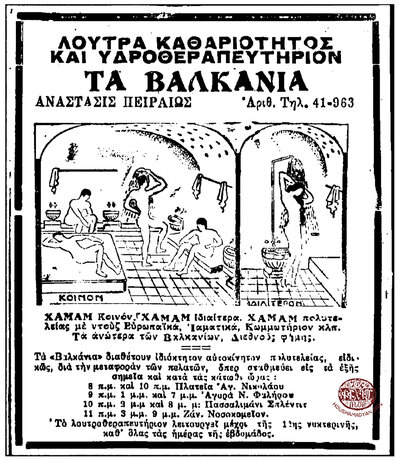

In 1933, Artin Palandjian opened the Balkania or Palandjian Public Baths in the Drapetsona area, near Piraeus. At the time, public health issues were rampant and difficult to overcome. Homes were not equipped with bathrooms, and in the midst of a drought, the size of the population had skyrocketed due to the arrival of a large number of refugees. Public baths had become a sanitary necessity, and many public and private bathing facilities were built in Piraeus and other Greek cities. Some of these were built in the eastern style (hamams), while others were medicinal spas of the European tradition.

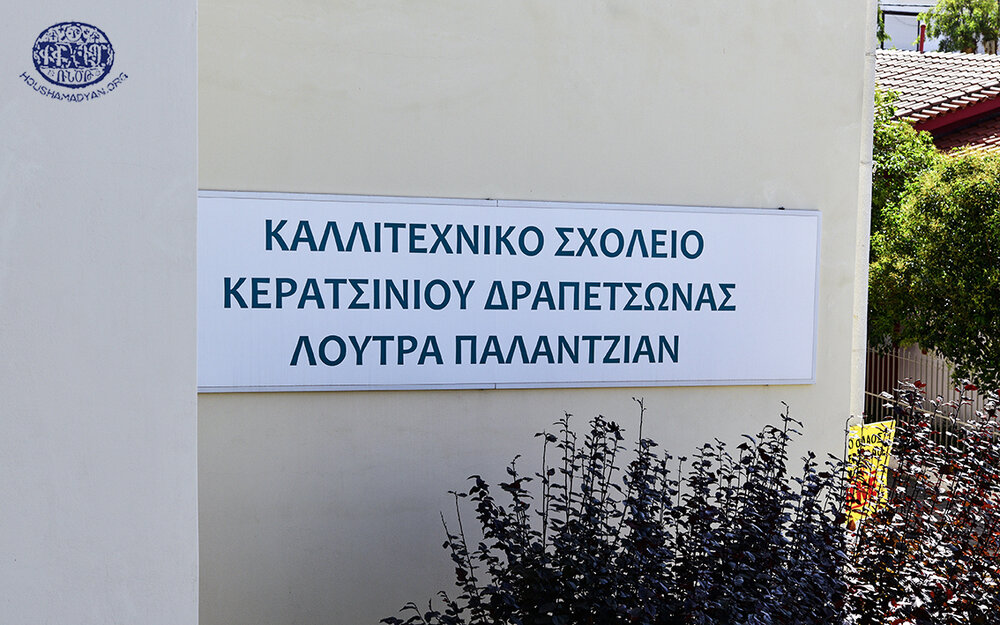

The Balkania (also known as Palandjian) provided both eastern and western baths. The facility was renowned throughout the region for its size and opulence. The workers were Armenian, and members of the Palandjian family and various relatives were part of the staff. Locals of all classes, sexes, and nationalities visited the baths. The main bathhouse, walled with marble, consisted of an anteroom, where the customers left their clothing, and the bathing room where they bathed and rested. This main bathhouse had a marble dome, with a circular glass window at the very peak, which allowed sunlight to penetrate. The marble walls were equipped with bed-shaped imposts, which radiated heat thanks to hot water circulating through them in a pipe. There was also a small marble pool, with both cold and hot water. In addition to this main bathing facility, there was a “hamam” in a six-cornered room, ringed by a circle of small and shallow pools, in which the customers washed their feet. In the center if the “hamam” was another six-cornered marble bath, reserved for women. The Balkania Baths were built on a large estate, with a huge palm tree standing in the garden. The facilities also included a coffee house, where the clients, especially on Saturdays, enjoyed snacks and drinks. The Balkania Baths operated for approximately 40 years. The architecture of the building has been preserved. Today, the building houses a beautiful art school.

The building of the Balkania Public Baths (also known as Palandjian Loutra), as it stands today. The building currently houses an art school.

The building of the Balkania Public Baths (also known as Palandjian Loutra), as it stands today. The building currently houses an art school.

The Years of the Second World War

In 1930, Artin, Yeranouhi, and their children moved to the Psychiko area of northern Athens. From a young age, Onnig Palandjian also became involved with the family business, helping to expand and grow it. He traveled to various European countries (England, Sweden, Germany, Austria) to purchase weaving looms of the Jacquard brand. By then, machine weaving was already highly advanced in these countries.

During the Second World War, when Greece was occupied by German forces, all factories in the country ceased operating. All the textile and products of the Palandjian weaving company were transported to the family home in Psychiko, but the Germans eventually found the hidden items and requisitioned them. Still, Onnig did not remain idle. During the wartime years, he engaged in the trade of gold on international markets, securing large profits. After the end of the war, the factories of Greece were reopened, and the Palandjian weaving company resumed business under the name of the Palatex Company, which still exists today.

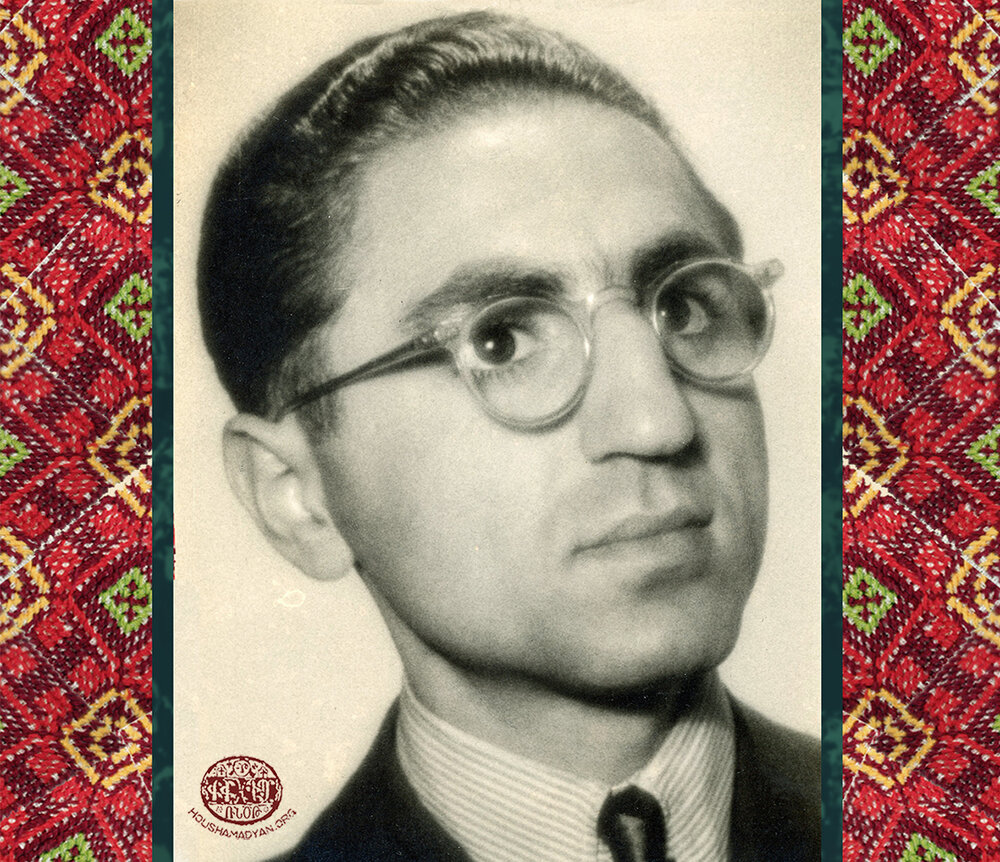

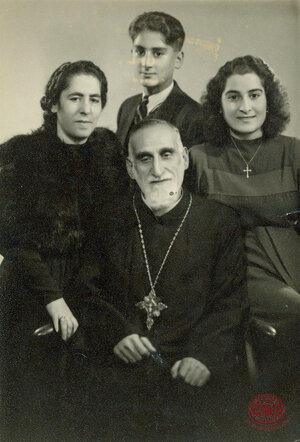

Onnig Palandjian and Andrine-Takouhi Utudjian

In December 1943, Onnig Palandjian traveled to Vienna to purchase German weaving machinery. There, he met Adrine-Takouhi Utudjian (in her Greek-language memoirs, Adrine spells her surname Outoundjian). Adrine, who was fluent in German, was hired to oversee the Palandjian weaving company’s correspondence with German factories. Throughout the years of war, Adrine was always ready to help anyone in need in Vienna.

Adrine and Onnig fell in love. They were engaged in Vienna, and then married in a civil ceremony. With the Second World War still raging, the couple decided to move to Greece. But the journey from Vienna to Greece was a lengthy adventure that lasted a full 29 days. Finally, Adrine and Onnig reached Pyschiko, utterly exhausted. A few months later, the couple were also married in a religious ceremony.

In 1945, the Greek Civil War began, and the country faced an extremely unstable political and economic situation. Onnig decided to emigrate to Argentina, and to open a weaving factory there. At this time, a large number of Greeks were emigrating to North and South America, principally Canada and Argentina. Hundreds of families were leaving Greece and settling down in Montreal and Buenos Aires. Onnig, too, traveled to Argentina, while his family remained behind in Greece. Presumably, Onnig’s journey took place in 1946. But soon, the wave of immigration into these countries abated when their governments began creating various obstacles for new arrivals. As a result, many would-be migrants returned to Greece. In his turn, after spending two years in Argentina, Onnig returned to Greece and reunited with his family. A short while later, he departed again, this time for the city of Manchester in England, where he spent six months learning how to operate weaving machines of the Jacquard brand. He then returned to Greece.

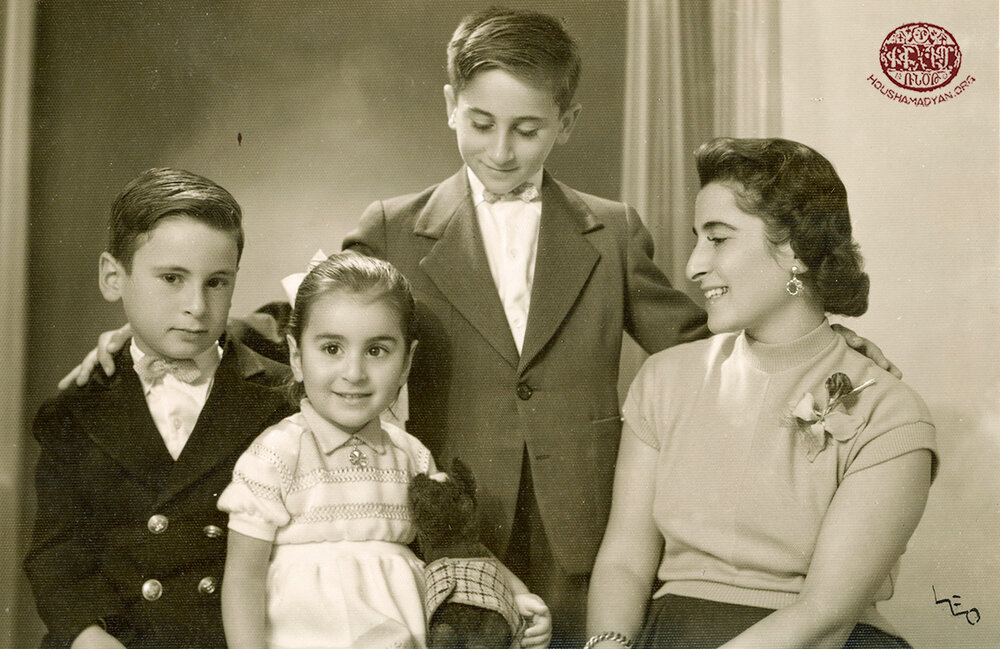

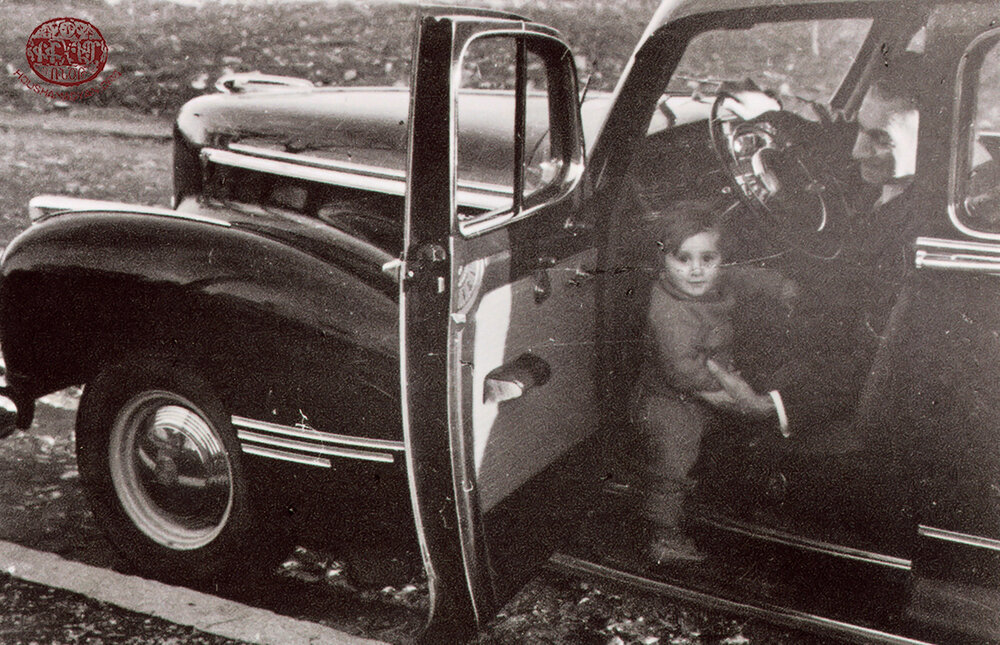

Onnig and Adrine had four children: Artin (born in 1945), Serko (born in 1949), Alice (born in 1953), and Zabel (born in 1966). Artin became a machinist, specializing in weaving machines. Serko is the director of the Palatex Company to this day. The company’s old weaving factory was shuttered in 2008. Another building was built on one-half of the property, while the buildings on the other half will soon be demolished. Also in 2008, the offices of the Palatex Company moved across the street from the old weaving factory. The company continues to operate today, with Alice in charge of sales and Zabel serving as the company’s insurance advisor.

Artin Palandjian died in 1947. His wife, Yeranouhi, died in 1969.

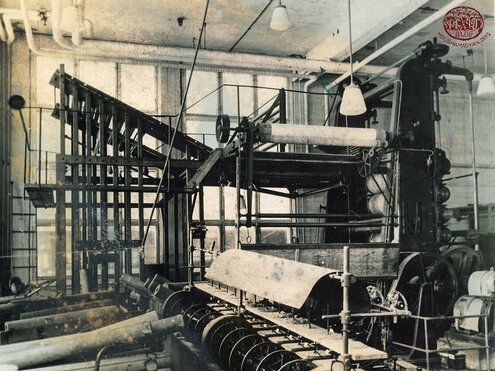

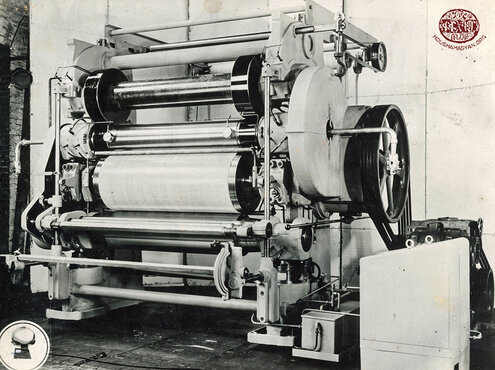

Photographs from inside the Palandjian weaving company. The factory has been closed since 2008.

Photographs from inside the Palandjian weaving company. The factory has been closed since 2008.

The Utudjian Branch (Van, Constantinople, Romania, Vienna, Hungary, Bulgaria)

Adrine-Takouhi Utudjian’s paternal grandfather, Apraham Utudjian, hailed from the city of Van. Apraham emigrated to the city of Constantinople at the age of 13. In 1895, during the massacres of Armenians unleashed during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, all members of his family were killed. After arriving in Constantinople, Apraham was provided with accommodation by Kevork Sahagian, who did all he could to help the teenaged boy start a new life. Apraham began working in Kevork Sahagian’s printing business, initially delivering newspapers, but later also taking on the duties of a reporter, which allowed him to enter the field of journalism. Gradually, the articles he wrote secured his reputation in the Armenian media. Unfortunately, we do not know which Constantinople-based Armenian newspapers published his articles.

In Constantinople, Apraham met Takouhi (maiden surname unknown). The two fell in love and married a month later, in February 1888. Their son, Krikor, was born in 1889. Then, Apraham was arrested by the Ottoman authorities and vanished. In her memoirs, Adrine does not specify the date of Apraham’s arrest. We presume that he was arrested during the Hamidian massacres.

Takouhi, now alone, spared no effort to provide her children with the best possible education and schooling. Krikor attended the Aramian School (later called the Aramian-Oundjian School) in the Kadukugh (Kadıköy) neighborhood. He was also a member of the acolytes’ choir of the neighborhood church. Takouhi died of tuberculosis. We do not know exactly when, but Krikor was only nine years old at the time. Krikor was a brilliant student. He was provided with a small room at the Aramian School, where he lived. He was one of the school’s best students. By the time he was 14 years old, he was fluent in Turkish, English, Armenian, German, and French.

After graduating from the school, Krikor worked as a teacher in the same institution. Then, the school’s leadership proposed that he and a few other former students travel to Romania and work there. Once in Romania, some of these youths served as teachers in local Armenian schools, while others served as reporters in local Armenian newspapers. For three years, Krikor was the conductor of the acolytes’ choir of the Armenian church in the Romanian city of Suceava. Then, he traveled on to Bulgaria, where he worked as a teacher.

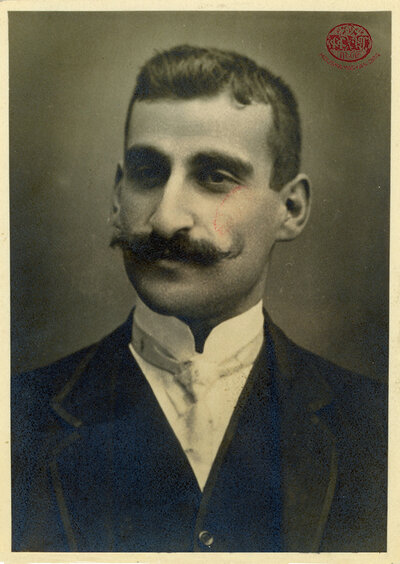

In 1910, Krikor settled in Vienna. He lived in the home of Sdepan and Dirouhi Simonian, and worked in his landlord’s rug store, which sold eastern rugs. Krikor also made the acquaintance of the Armenian priest of Vienna and began attending Sunday services. Krikor was completely fluent in German and Turkish, and thanks to this skill, he was employed as a Turkish language and history teacher at the Berlitz Foreign Language Institute in Vienna.

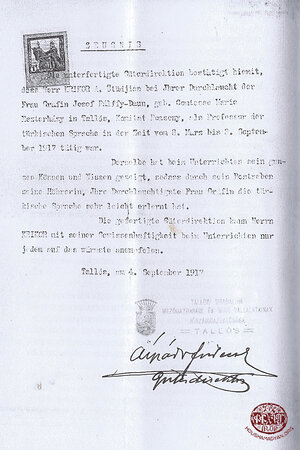

Krikor’s career flourished. In 1917, he was invited to the Hungarian palace in Tallós (present-day Tomášikovo, Slovakia), to teach Turkish to Countess Marie Esterházy, wife of Joseph Palffy-Daun. Krikor moved to Hungary, where he lived in great opulence. But he found this new life monotonous. Just five months later, he returned to Vienna and resumed his teaching career.

Back in Vienna, Krikor worked as a lecturer of Turkish in a local university (name unknown). But he did not enjoy this new position for long. In December 1917, he was arrested by the Austrian police for desertion from the Ottoman army. The decision was made to extradite him to the Ottoman Empire. These events occurred during the First World War, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was allied with the Ottoman Empire. Escorted by police officers, he set out for Constantinople. On the journey, the group stopped in Sofia (Bulgaria), where Krikor fortuitously ran into an old schoolmate, Hagop Beorekdjian. With the latter’s help, he escaped his police escort. Hagop even provided Krikor with a room, where the latter lived secretly for six months. During the months of his imprisonment, Krikor learned Bulgarian. Then, Hagop performed another miracle by obtaining a fake passport for Krikor, in the name of Aram Utudjian.

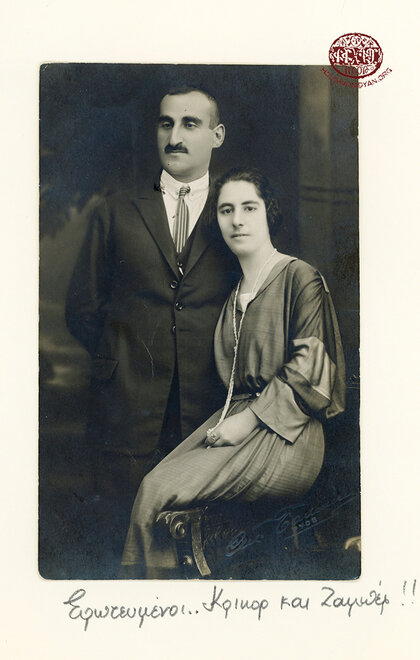

Krikor (now called Aram) immediately rented his own home in Sofia and began working as a treasurer in a German bank. On Sundays, he also served as a deacon in the Saint Hagop Church. Krikor’s life returned to normal. One Sunday, after church services, he made the acquaintance of Zabel Kestanian. They immediately fell in love. They were engaged in a solemn ceremony in 1923, after which they were married in a religious ceremony. In 1925, the couple’s first child, Adrine-Takouhi Utudjian, was born in Sofia.

The Kestanian family hailed from Agn. Zabel was the daughter of Nigoghos Kestanian, who had emigrated from Agn to Constantinople, then to the Bulgarian city of Ruse (formerly known as Rustchuk). Nigoghos was married to Minever, who was a native of Constantinople. The couple had 12 children, of whom only five survived infancy: four daughters, Filomen, Kohar, Zabel, and Eliz; and one son, Kevork.

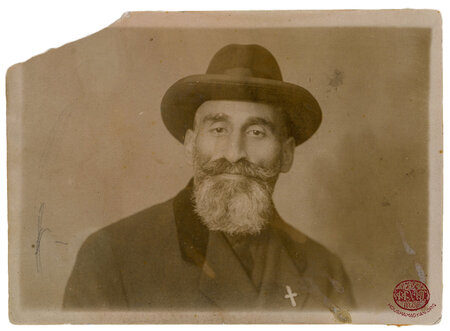

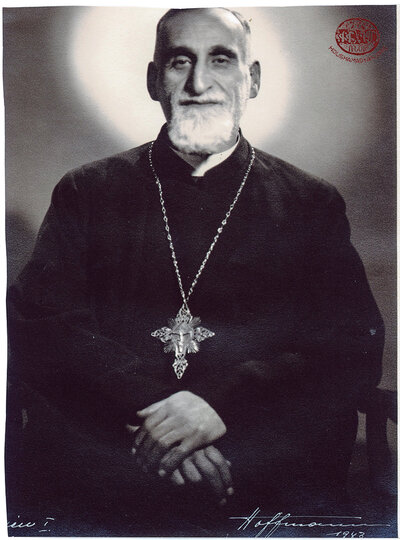

In 1927, in Bulgaria, Krikor was ordained as a priest by prelate Archbishop Sdepanos Hovagimian. Krikor was styled Father Yeghishe Utudjian. He then returned to Vienna, where he began serving as the pastoral leader of the city’s Armenian community.

The couple’s second child, Aram, was born in 1929. The Armenian church of the city, housed in a large hall on the sixth floor of a building, was adjacent to the Utudjian family home. From the hall, three steps led up to the altar, which was lined with vermilion curtains on both sides. On the altar was an 18th century icon depicting the Virgin Mary. Two meters from the altar was the church organ. The walls were covered with vermilion wallpaper and adorned with icons. On the right of the altar was a depiction of the battle of “Vartanants.”

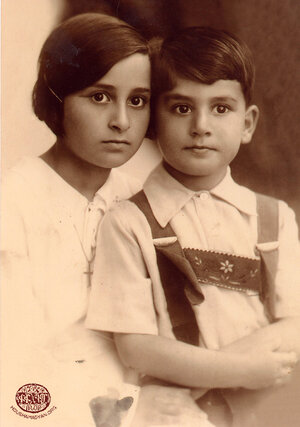

Adrine-Takouhi and Aram were enrolled in one of the city’s best schools. As Adrine-Takouhi had a great love for singing and music, she attended the Vienna Ecclesiastical Music College, and achieved great successes as a pianist and in the field of ecclesiastical music.

On the eve of the Second World War, Austria became a part of Nazi Germany when German forces invaded the country in the Anschluss of 1938. Soon, the world war erupted. In her memoirs, Adrine describes the persecution of Vienna’s Jews by the Nazis.

As the war continued, basic food staples soon became rationed. Father Yeghishe Utudjian did what he could to help Jews and deserters from the army. He gave many of them shelter in his church. Many of these fugitives were Armenians who had served in the Red Army and had been captured by German forces during the war. In 1941, the Nazi authorities created the Ostlegion (Eastern Legion), a military unit reserved for the hundreds of thousands of Red Army prisoners held by the Germans. Most prisoners who enlisted in the Ostelgion were Russian and Ukrainian. In early 1942, individual legions were also created, consisting of prisoners of war representing Soviet soldiers from smaller nations. These included the Turkestan Legion (Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Turkmens, and Tajiks); the Caucasian Muslim Legion, which immediately changed its name and became the Azerbaijani Legion; the Georgian Legion; the Armenian Legion; the Northern Caucasian or Mountain Legion (Ossetians, Chechens, Abkhaz, etc.); and the Volga-Tatar Legion. These military units were expected to fight alongside ethnic German units against the Soviet Union.

During the years of war, Father Yeghishe was a trusted source of assistance for Armenians and Austrians seeking succor. Adrine, too, was involved in her father’s humanitarian work. As an Armenian who was fluent in German, she was often summoned to various Austrian ministries or to Gestapo office to interpret for Armenian-speaking prisoners whom the Nazis had captured. It must be noted that Adrine did more than simply translate – she often defended the prisoners and protected them from harsher punishments.

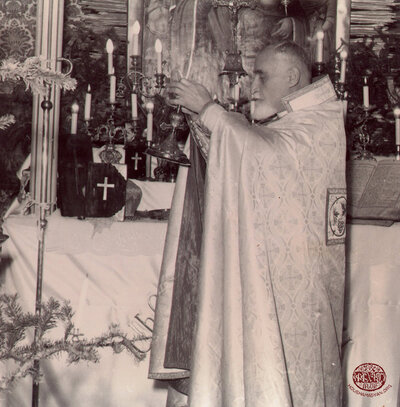

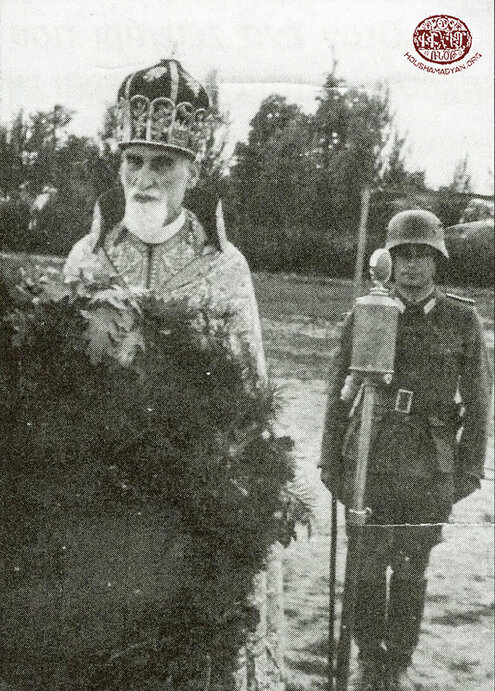

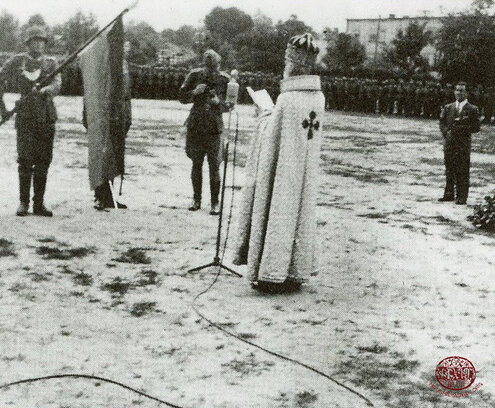

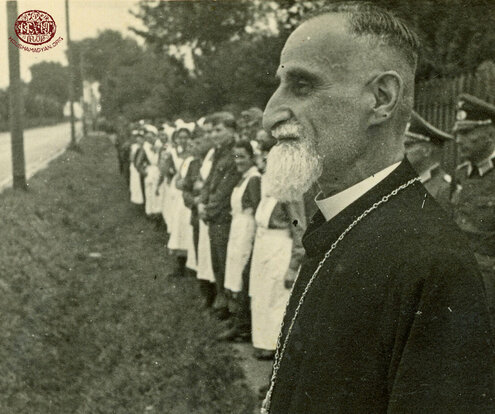

Father Yeghishe also wished to hold a service for the soldiers of the Armenian Legion serving in the German army. After lengthy negotiations, he received permission from the Nazi authorities to do so. Accompanied by members of the Armenian religious council of Vienna, he traveled to Poland, where the Armenian Legion was stationed. He held a service and distributed communion to the soldiers. Many of these men, who had previously served in the Red Army, had never entered a church or received communion.

Father Yeghishe Utudjian, photographed in Poland during the Second World War while leading a service for the members of the Armenian Legion serving in the German army (Armenische Legion). In 1941, the Nazi authorities created the Ostlegion (Eastern Legion), a military unit reserved for the hundreds of thousands of Red Army prisoners held by the Germans. Most prisoners who enlisted in the Ostelgion were Russian and Ukrainian. In early 1942, individual legions were also created, consisting of prisoners of war representing Soviet soldiers from smaller nations. These included the Turkestan Legion (Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Turkmens, and Tajiks); the Caucasian Muslim Legion, which immediately changed its name and became the Azerbaijani Legion; the Georgian Legion; the Armenian Legion; the Northern Caucasian or Mountain Legion (Ossetians, Chechens, Abkhaz, etc.); and the Volga-Tatar Legion. These military units were expected to fight alongside ethnic German units against the Soviet Union.

After the death of his wife, Zabel, Father Yeghishe visited Paris in 1949. The Armenian prelate of Paris, Archbishop Ardavazt Surmenian, presented him with a pastoral cowl and staff. Father Yeghishe then returned to Vienna, where he continued his pastoral service. He died in 1958.

As we have already seen, Adrine met Onnig Palandjian in Vienna. The two fell in love, then moved to Greece. From the 1960s to the 1990s, Adrine served as the chairwoman of the women’s committee of the Saint Krikor Lousavorich Church of Athens. She was also a poet. In 2008, she published her memoirs, which served as a primary source for this article.

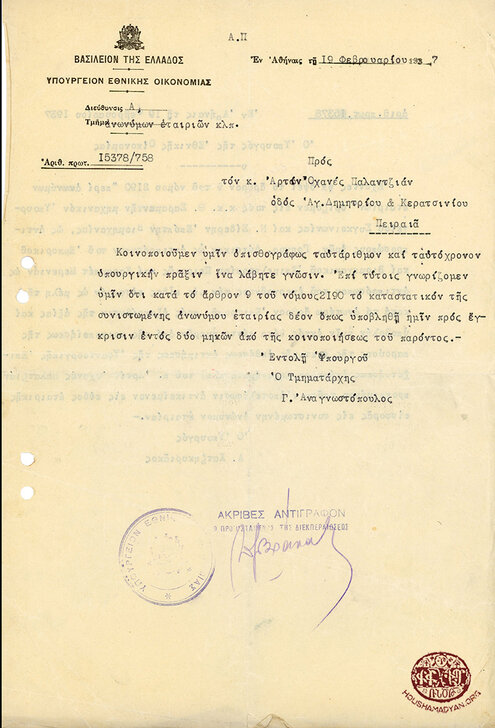

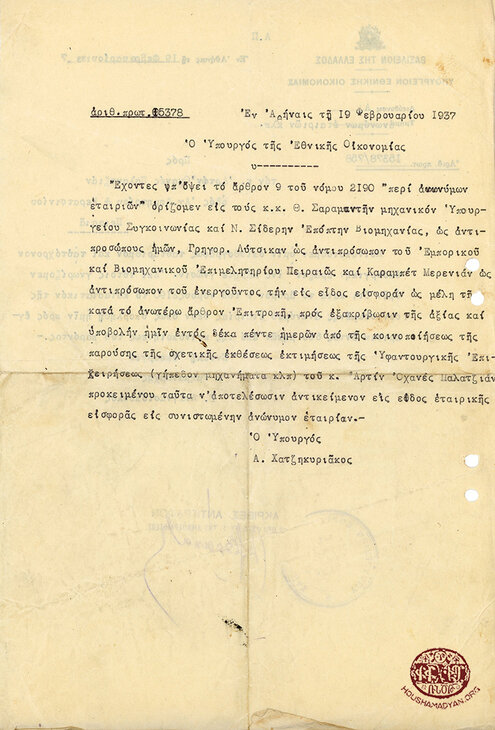

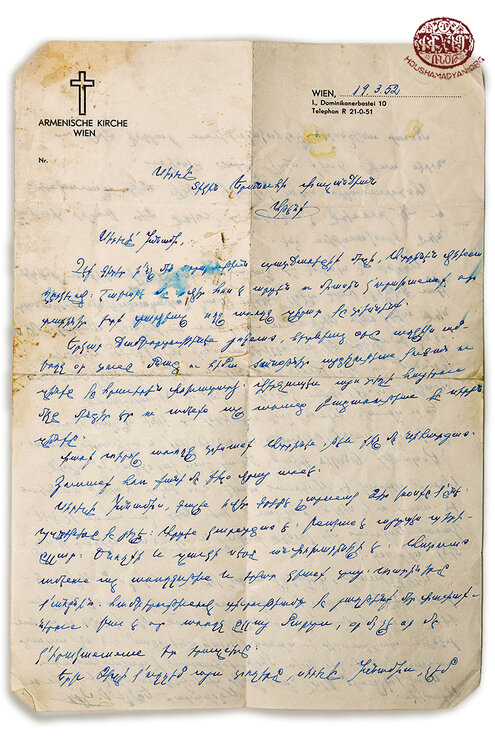

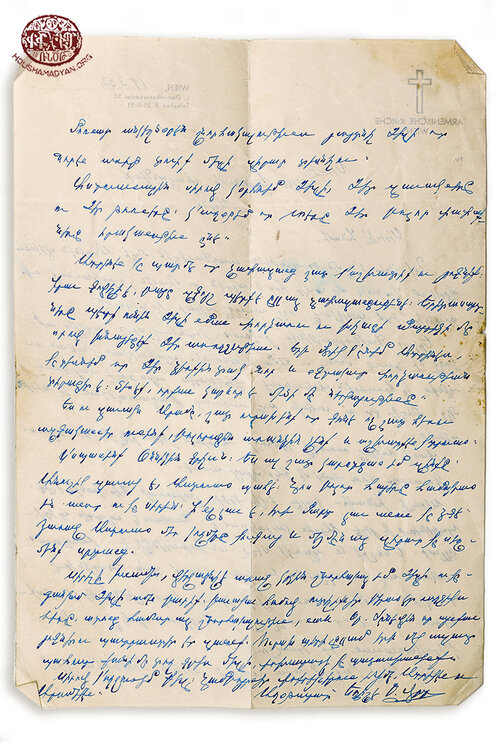

A letter from Senior Priest Father Yeghishe Utudjian (Vienna) to Yeranouhi Palandjian (Athens), dated March 19, 1952. In the letter, Father Yeghishe expresses his joy at having his daughter, Adrine Palandjian (nee Utudjian), visit him in Austria. The letter also provides the address of the Armenian Apostolic Church of Vienna at the time, I. Dominikanerbastei 10.