Araksi Kalousdian-Kavedjian Collection – Paris

26/10/23 (Last modified 26/10/23) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

The Kalousdian family hailed from Ordu. Among the family’s earliest ancestors were Hagop Kalousdian and his wife, Kayane Kalousdian (nee Djknavorian). Kayane was born in 1854, and was the daughter of Hampartsoum and Dourig Djknavorian. Hagop and Kayane’s son, Hovagim Kalousdian, was born in 1881. He was a chapouladji by trade – a maker of leather sandals. His workshop was located in Ordu’s Armenian artisans’ market. Hovagim had two sisters: Elmas, who was married to a Kalondjian and had children, one of whom was called Yervant; and Dikranouhi, who was married to an Adjarian and had two children, Souren and Siranoush.

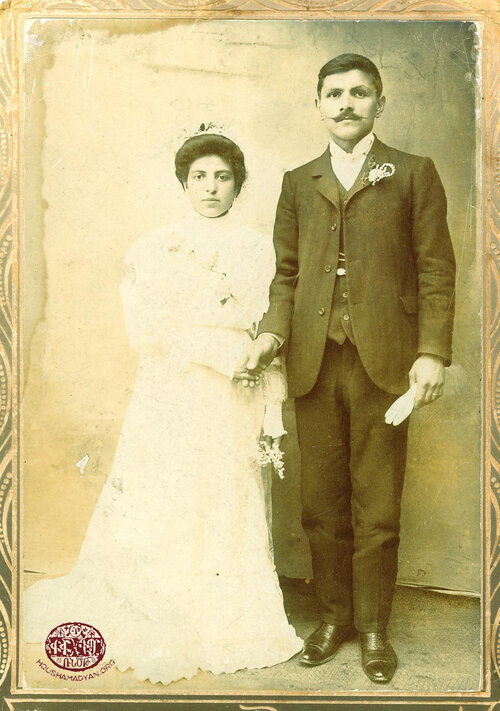

Hovagim married Dikranouhi (nee Vartian) on December 24, 1909. Dikranouhi was the daughter of Khachig (born in 1845) and Tshkho (born in 1854) Vartian. Khachigs’ parents were called Vartan and Zartok (?); and Tshkho’s parents were called Hagop and Mariam. Among Dikranouhi’s siblings was Dikran, born in 1887.

Hovagim and Dikranouhi had two daughters, Araksi (born in 1912) and Berdjouhi (probably born in 1914). Hovagim was an expert violin player. He often hosted gatherings in the family home, featuring music and singing.

In June 1915, the Ottoman authorities began arresting the Armenian adults in Ordu. Hovagim was among the detained men who were marched out of the city, and who then disappeared. Dikranouhi and another Armenian woman who had lost her husband in the same way decided to venture out of the city and seek their husbands. Before leaving, Dikranouhi entrusted her two daughters to a Turkish neighbor, Mahitap Hanum. Dikranouhi never returned to Ordu and was lost without a trace.

In 1915, the Armenian population of Ordu was deported en masse. But the two orphan girls, Araksi and Berdjouhi, remained under Mahitap Hanum’s care throughout the years of the Genocide. Later, one of Araksi’s sons, Krikor Kavedjian, would describe Mahitap Hanum as a “virtuous Turk.” After the end of the First World War, the two girls’ aunt tracked them down and informed Armenian community organizations of their situation. After the Armistice, such organizations were active in seeking out and providing aid to survivors of the Genocide. They focused on finding Armenian children, teenagers, and women kept in the care of Turkish, Kurdish, and Arab families, and placing them in orphanages or shelters.

We do not know how Mahitap Hanum and her family reacted when Armenians arrived at their door and asked that they hand over the two girls under their care. But we know that Araksi and Berdjouhi were sent to Constantinople, where they found shelter in Lord Mayor’s Fund Orphanage. At that time, Constantinople was occupied by British Forces. However, this situation did not last long. In late 1922, the Allied Forces evacuated the city and were replaced by nationalist Turkish forces, under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal (later Ataturk). Immediately before the evacuation of British Forces, numerous orphanages relocated from Constantinople to Greece, including Lord Mayor’s Fund Orphanage.

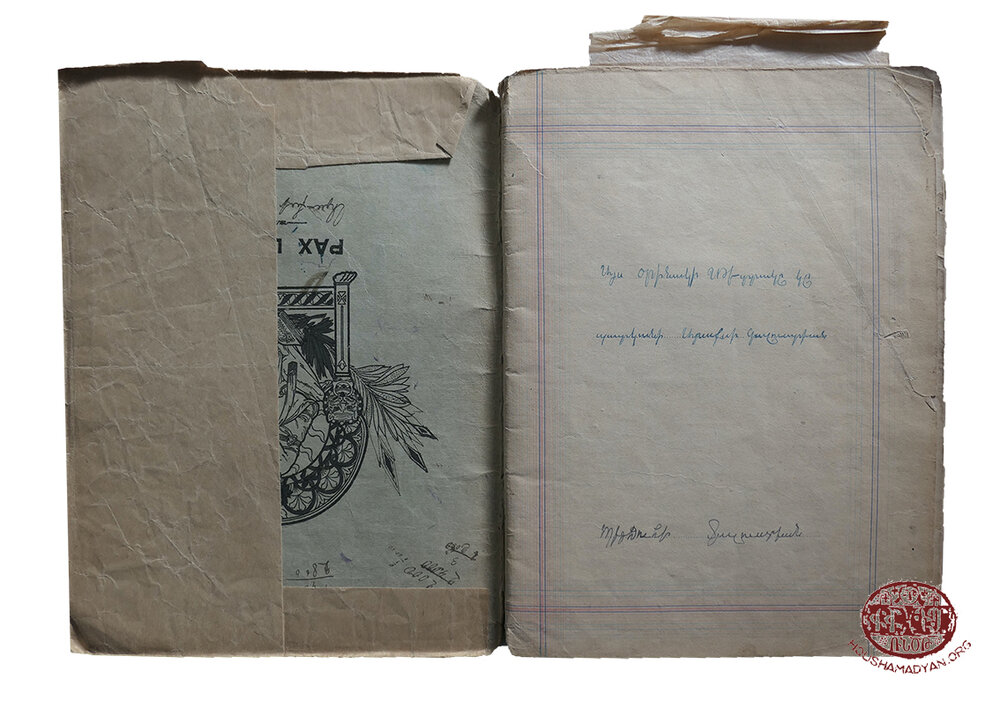

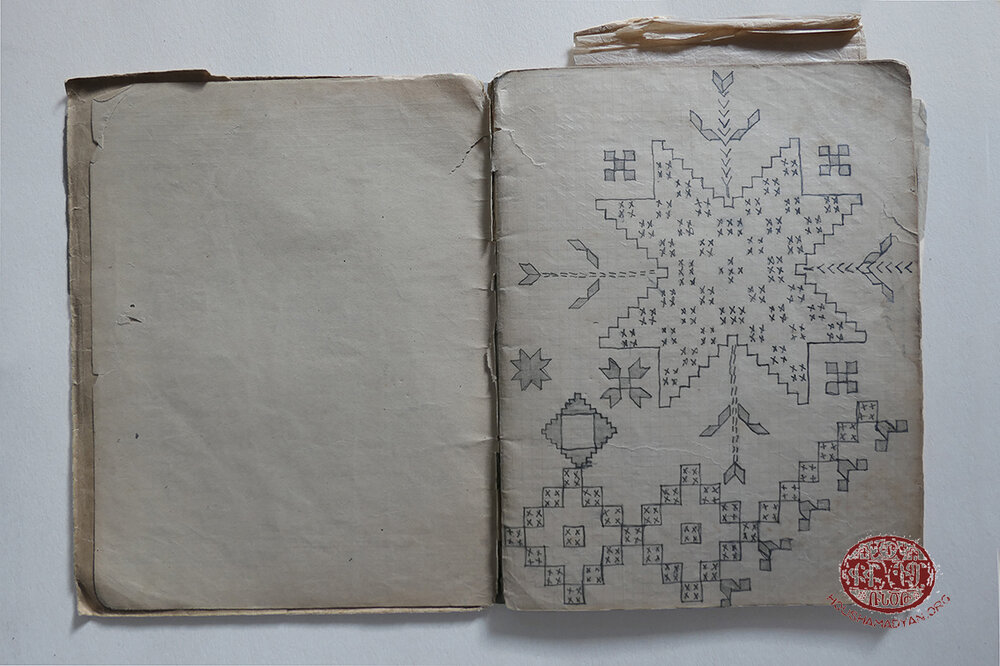

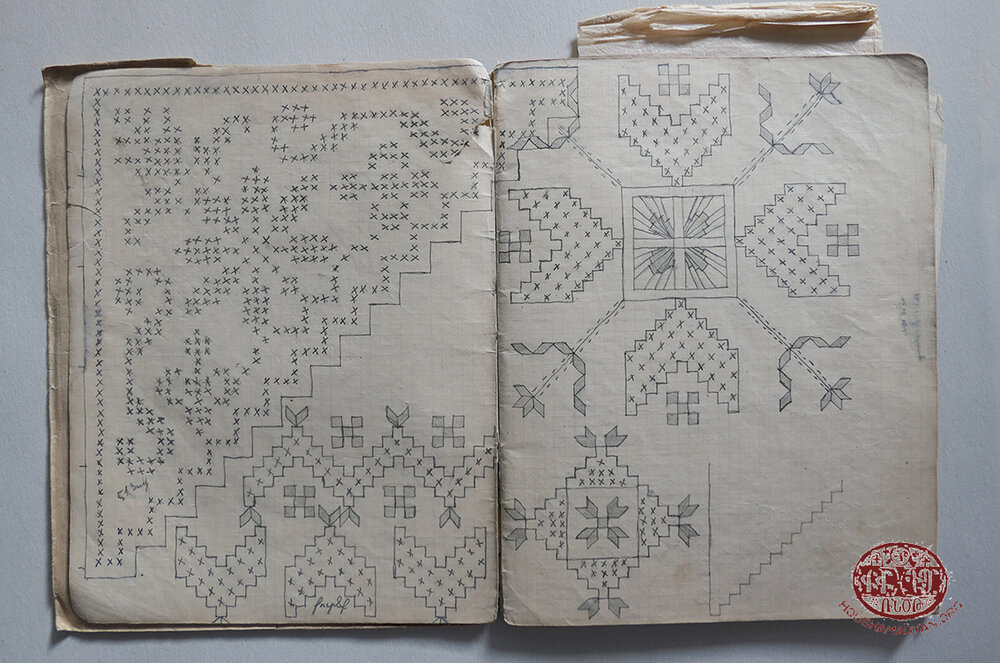

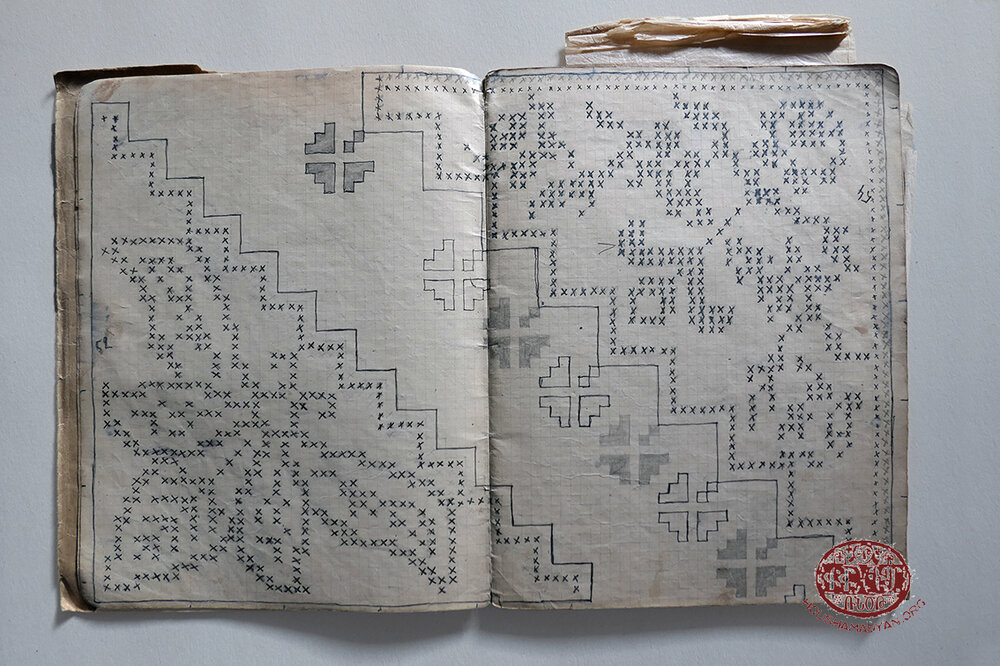

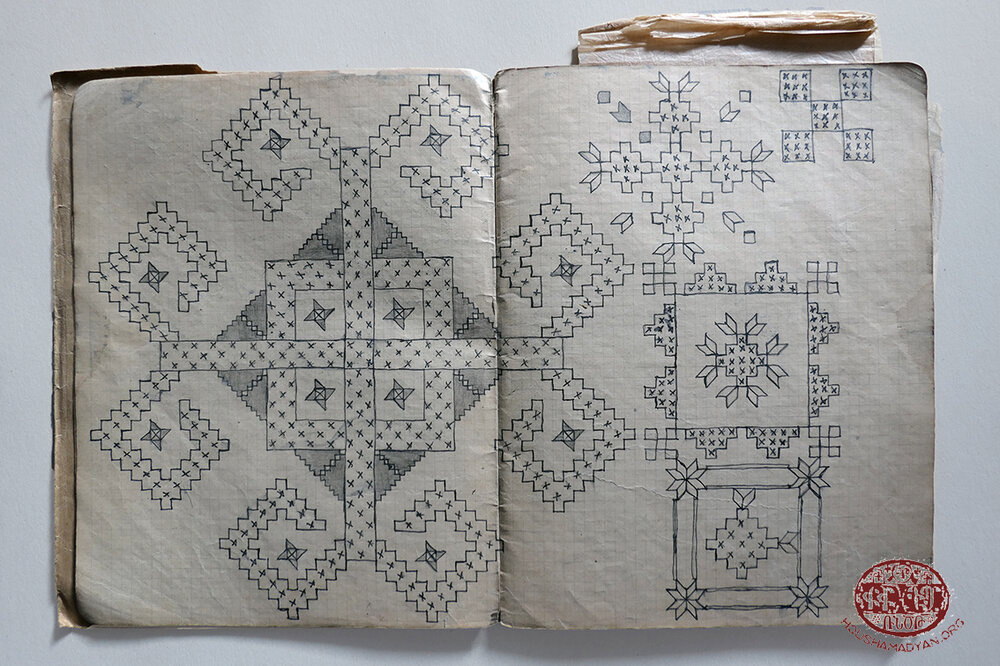

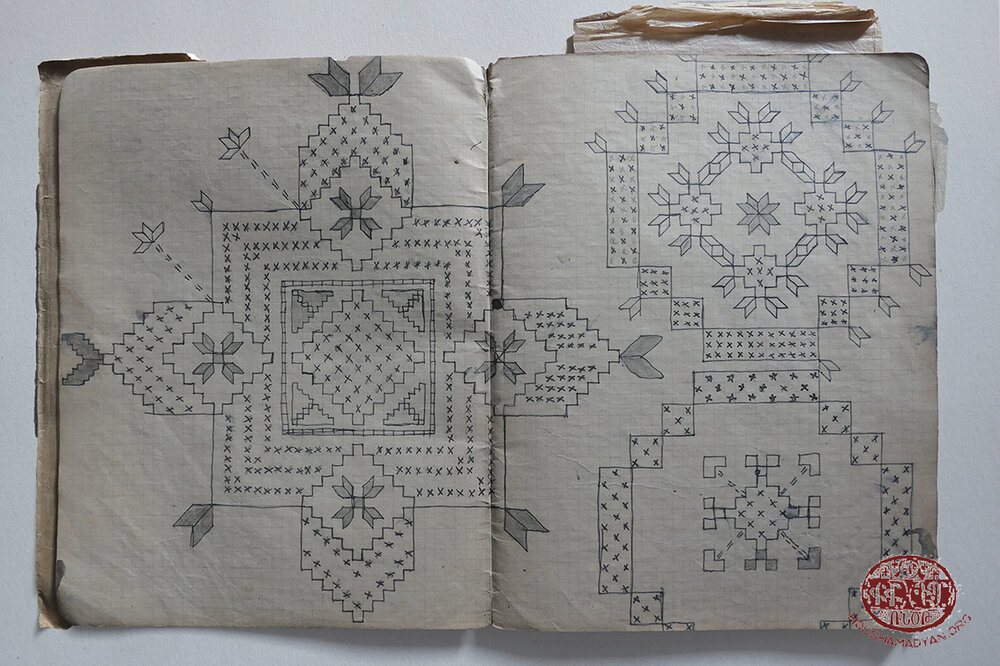

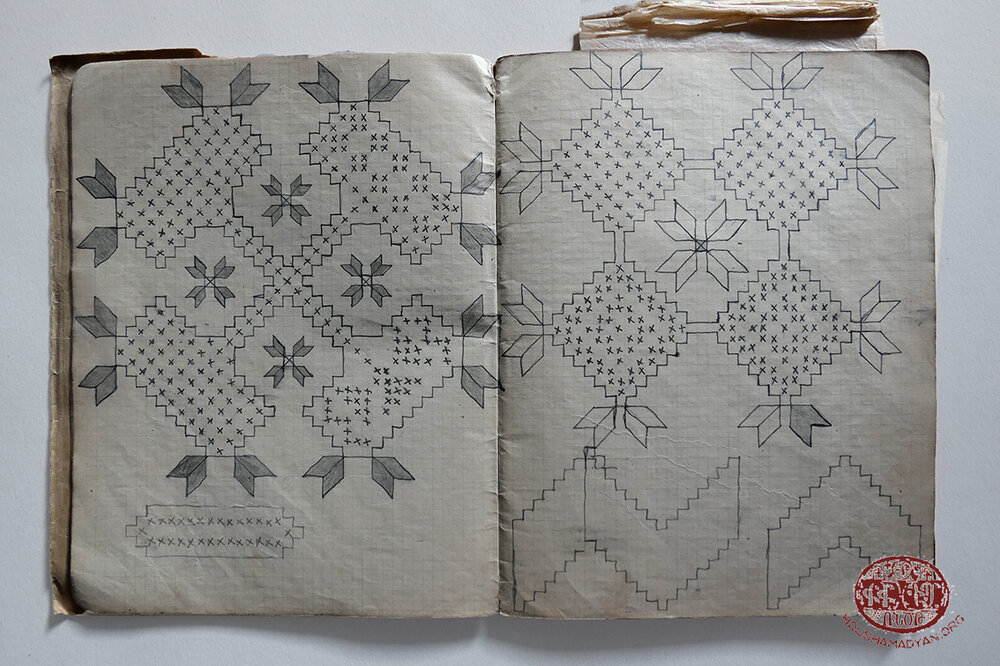

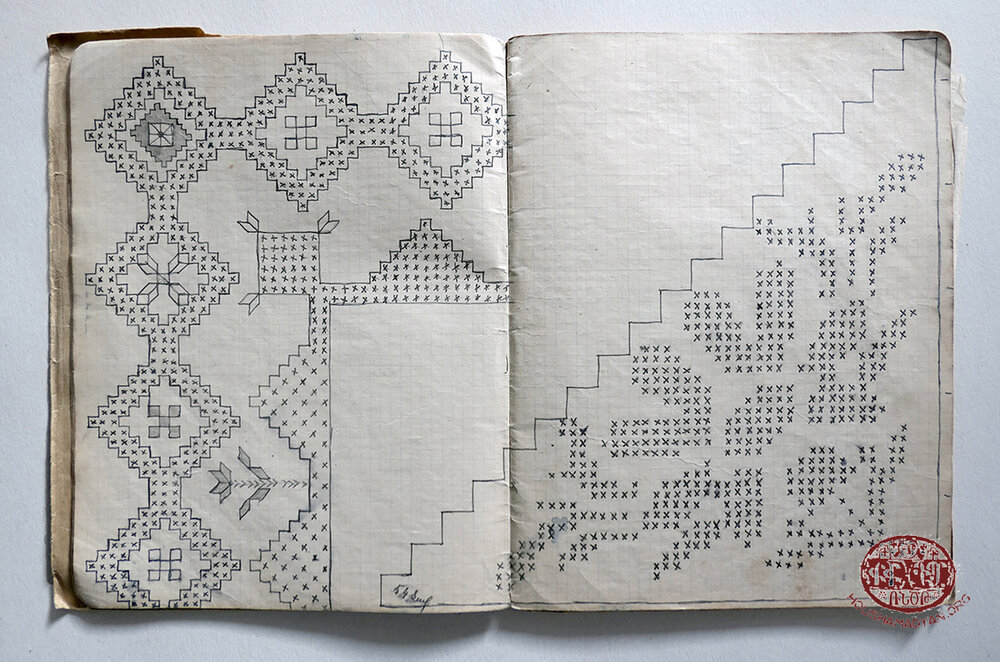

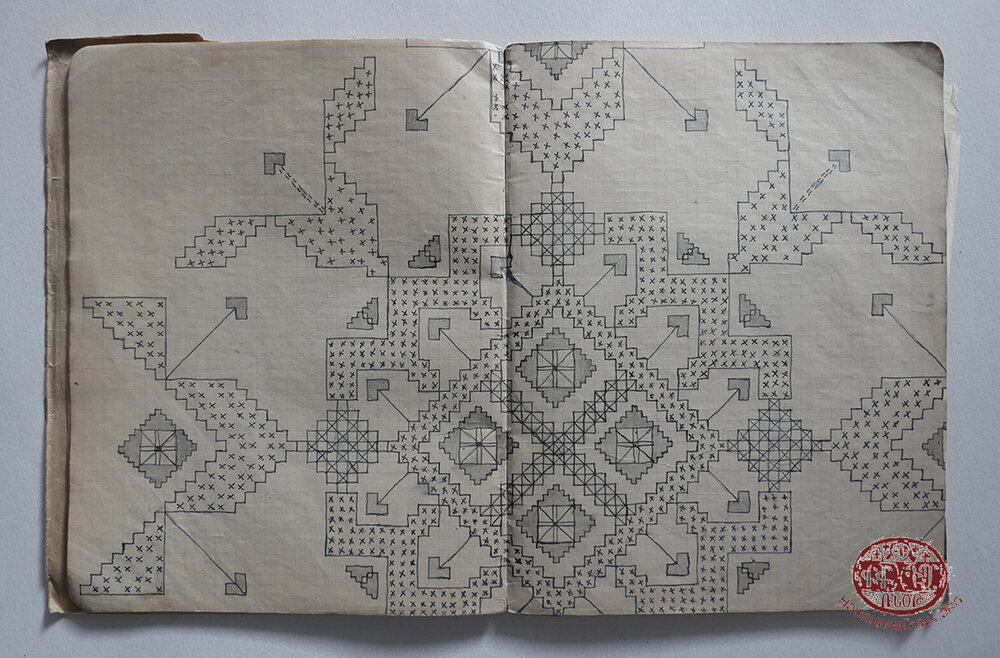

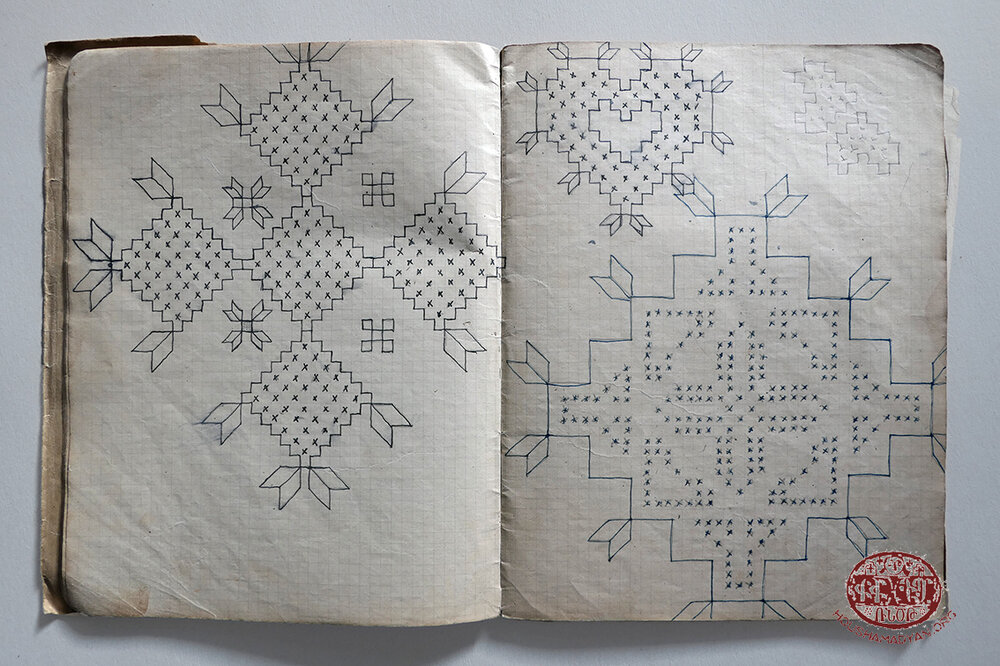

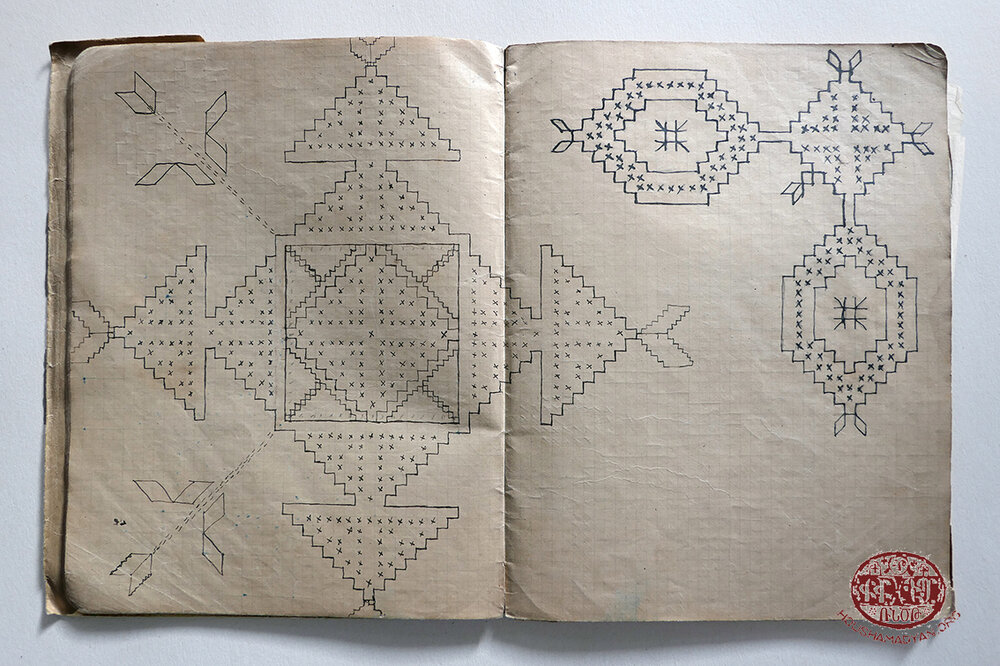

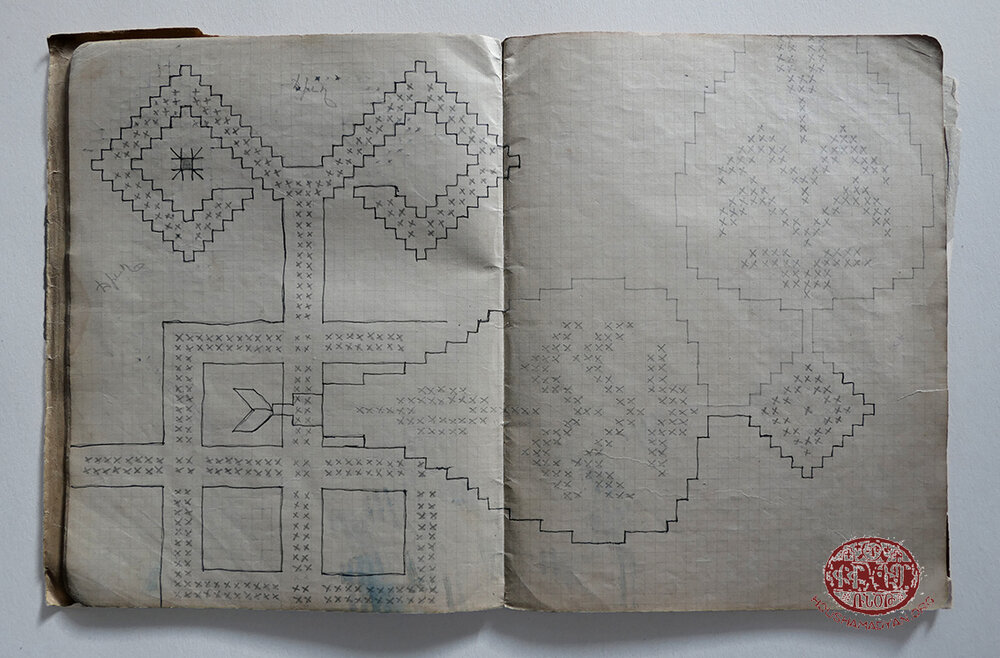

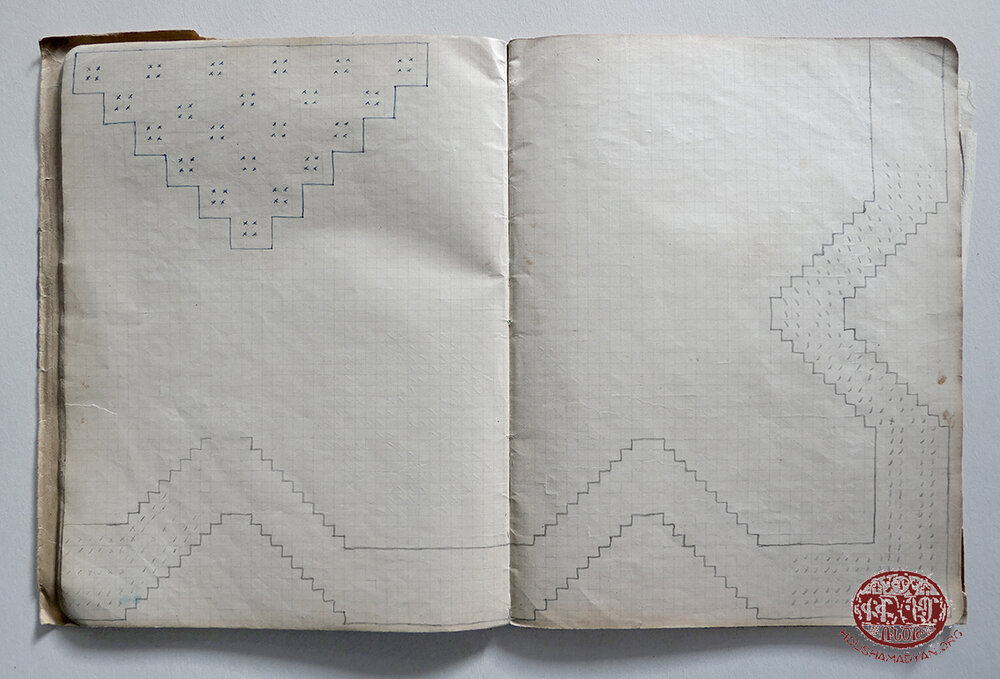

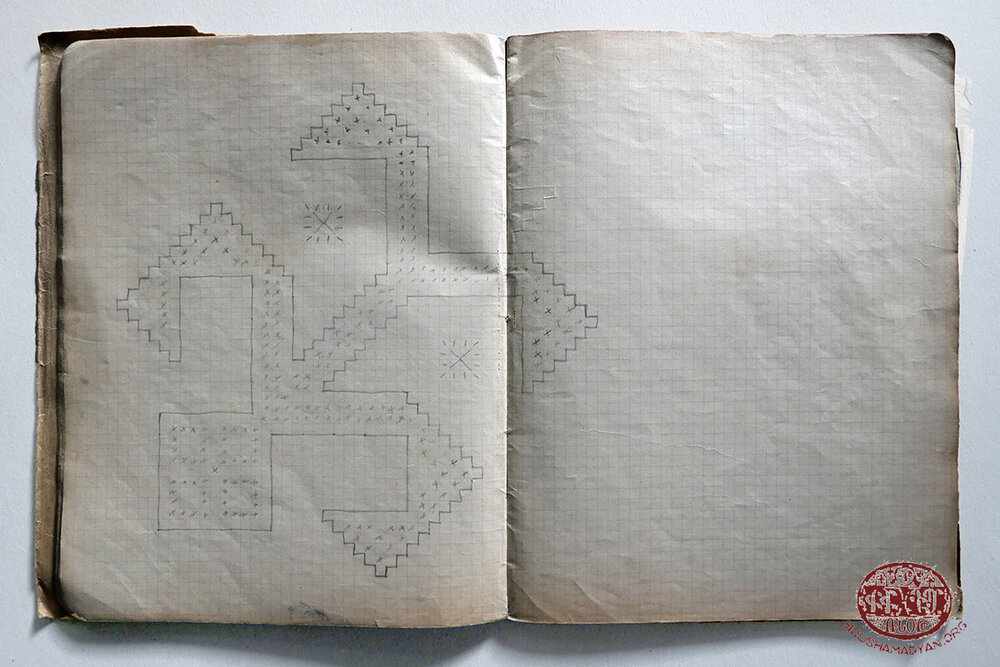

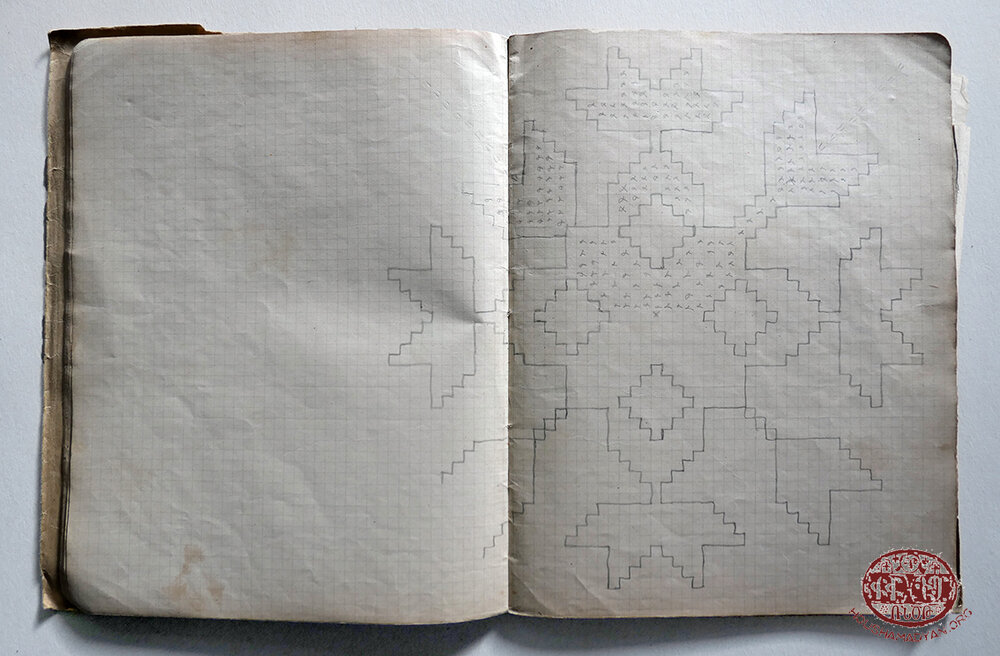

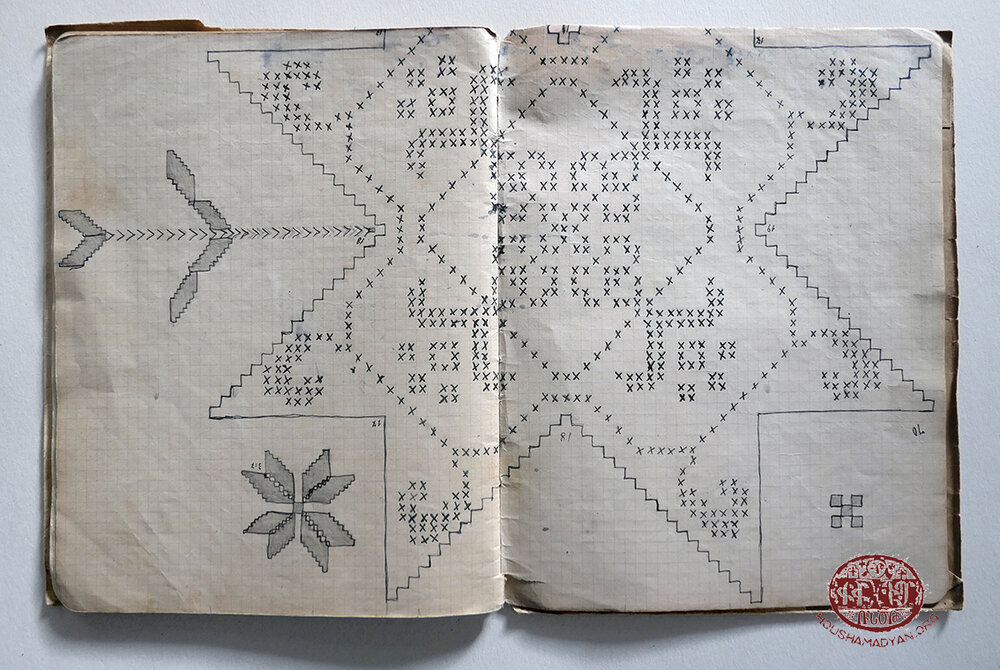

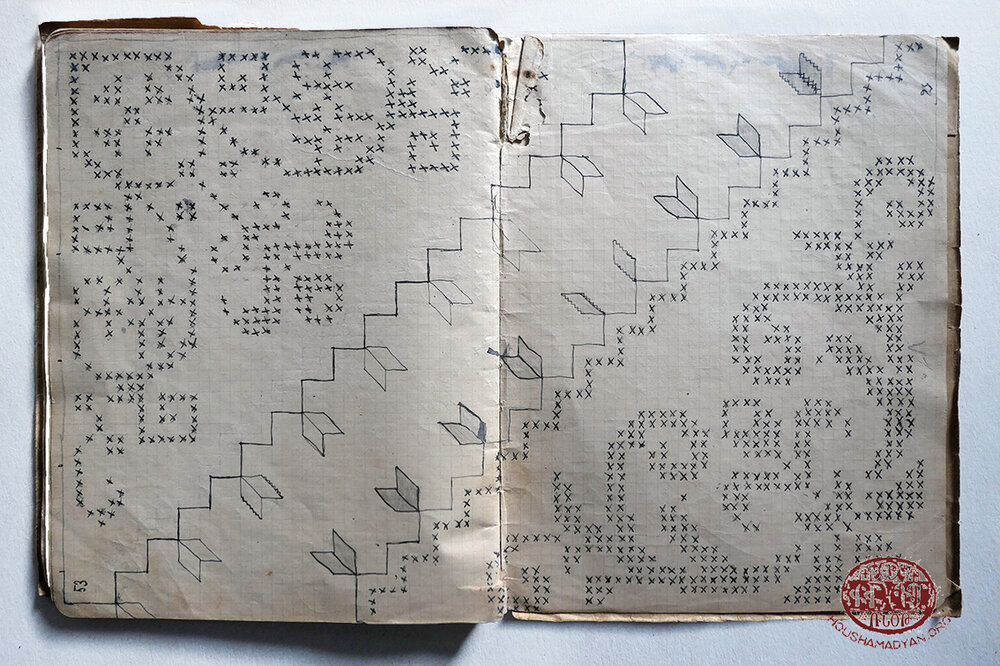

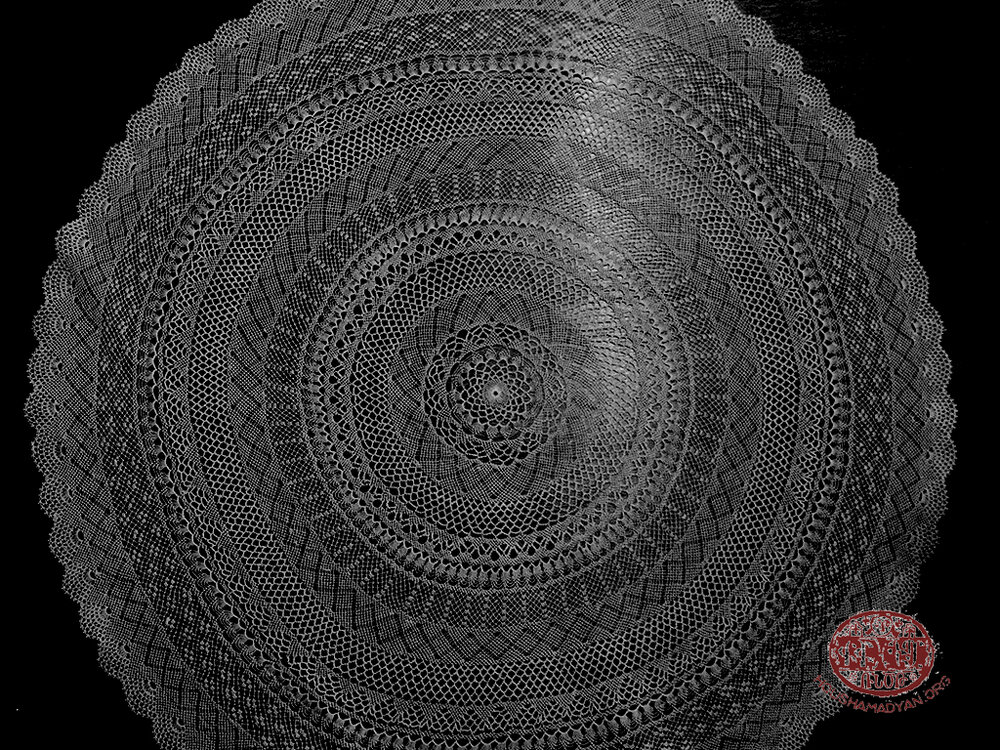

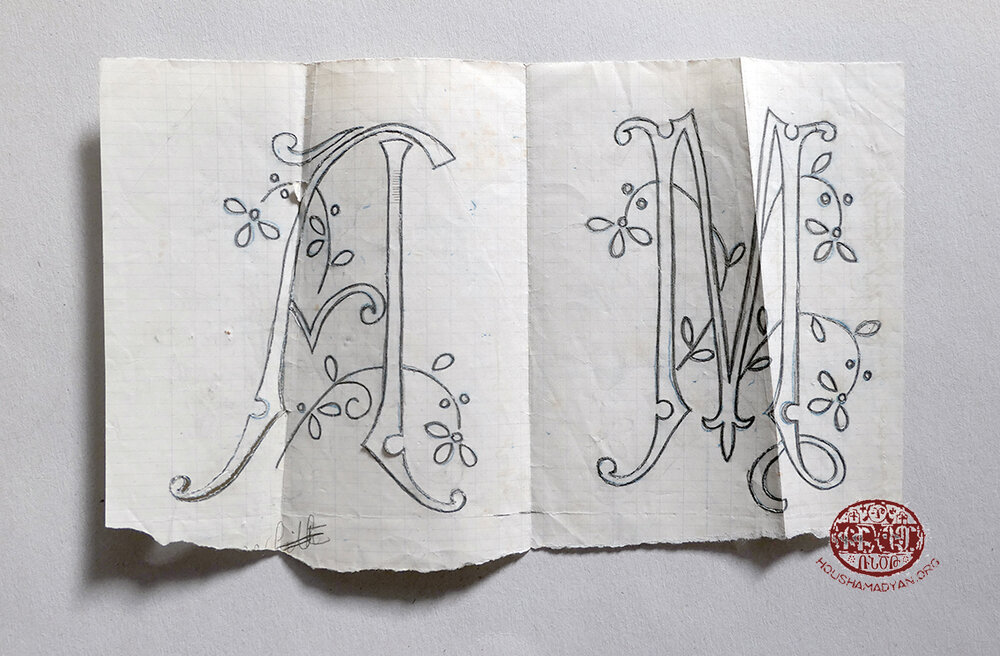

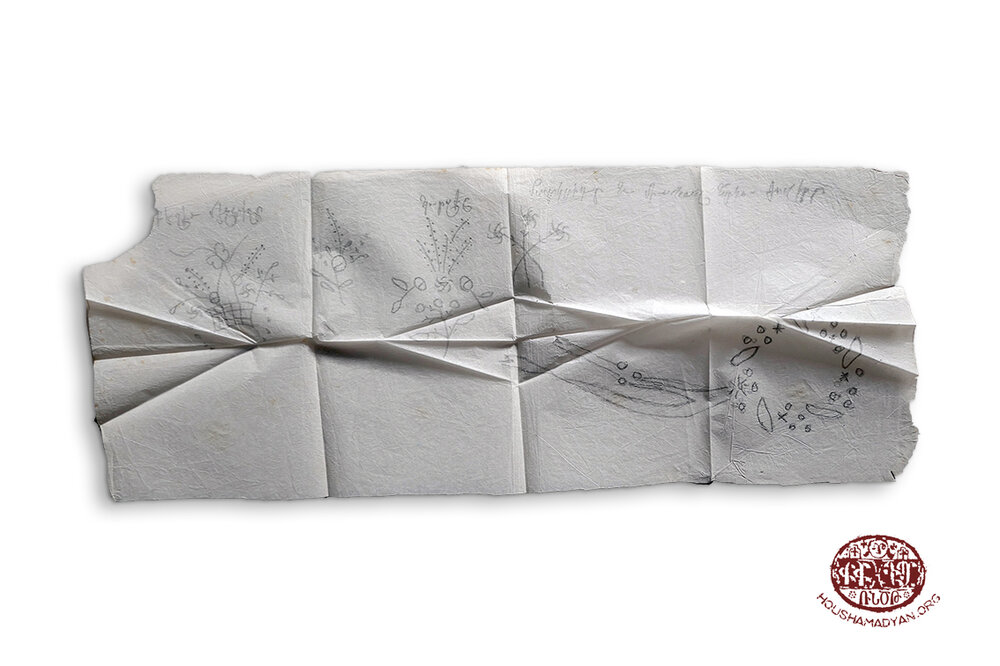

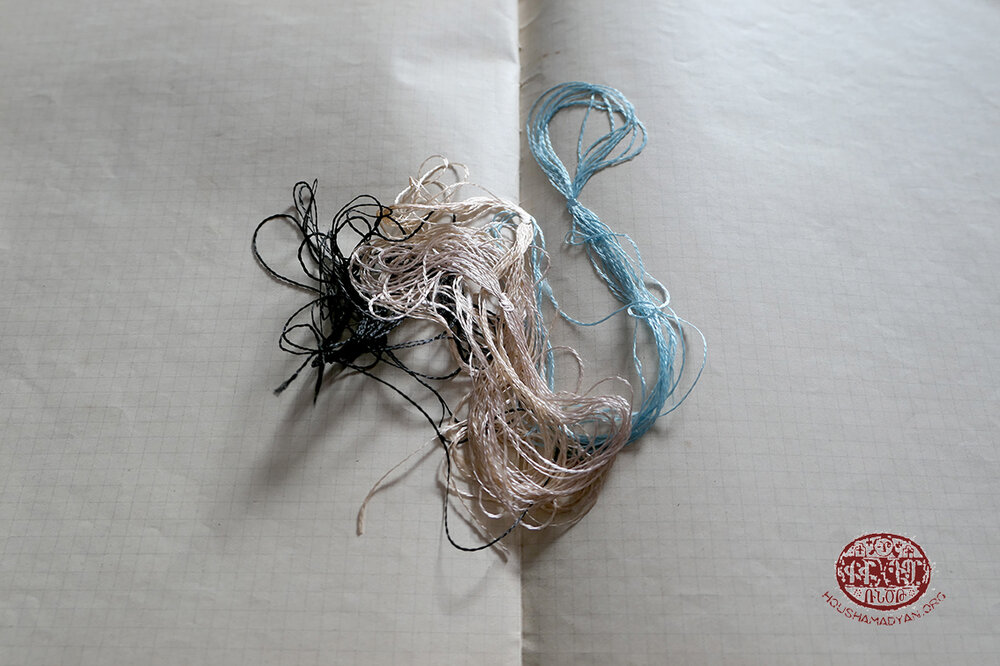

A notebook kept by the sisters Araksi and Berdjouhi Kalousdian, dedicated to embroidery. In it, the two sisters drew examples of embroidery patterns, which they probably replicated in their own work.

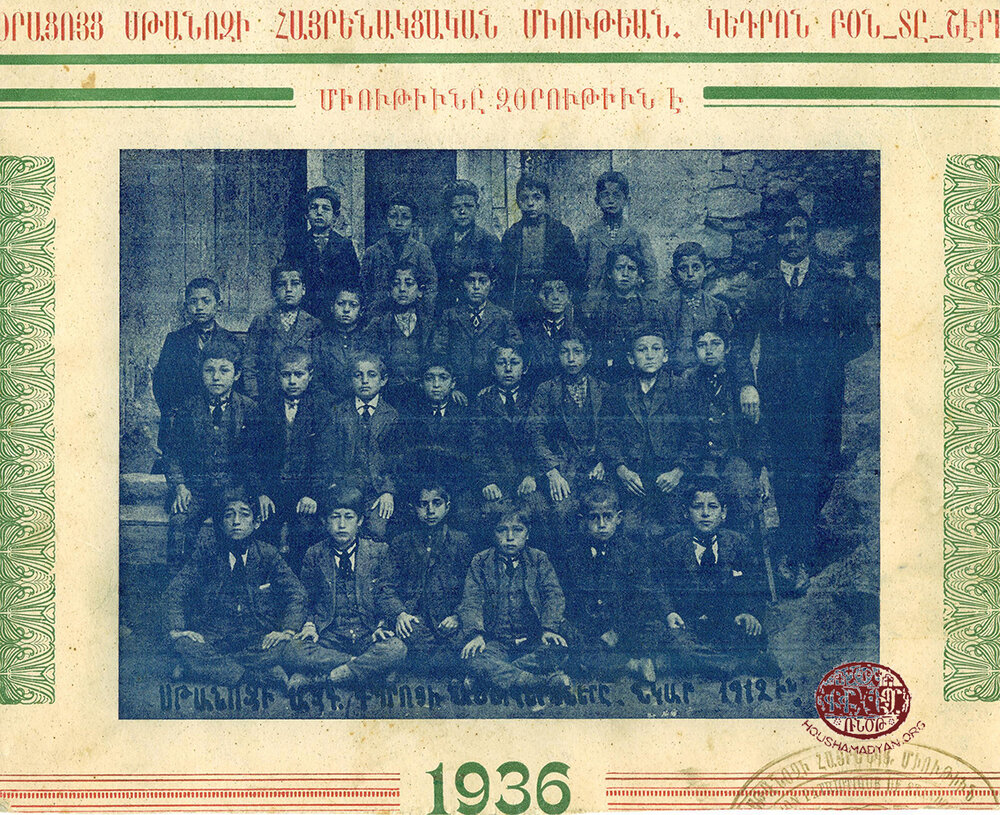

On November 22, 1922, Araksi and Berdjouhi arrived on the Greek island of Corfu (Kerkyra), where they continued living in Lord Mayor’s Fund Orphanage. On March 11, 1925, the two sisters moved to Marseille (France) and were accepted into the school-orphanage of the Tbrotsaser Association. This association was founded in 1879, in Constantinople, and had been involved in the field of Armenian education for decades. After the Genocide, the organization opened a school/orphanage in Constantinople, which relocated to the Greek city of Thessaloniki in late 1922, and then to Marseille in 1925.

In 1928, the school relocated again, this time to Paris, specifically to the northern Parisian suburb of Le Raincy. At the time, Araksi was 16 years old, and Berdjouhi was 14. They, too, moved to Paris with the school. Their aunt, Perig, had survived the Genocide, and we know that she corresponded with her orphaned nieces. She tried to help them in any way she could, but she did not have the financial wherewithal to adopt them. She worked as a cleaner, and her wages were modest. She had become widowed during the years of the Genocide, and cared for her two daughters, Nvart and Hasmig, alone.

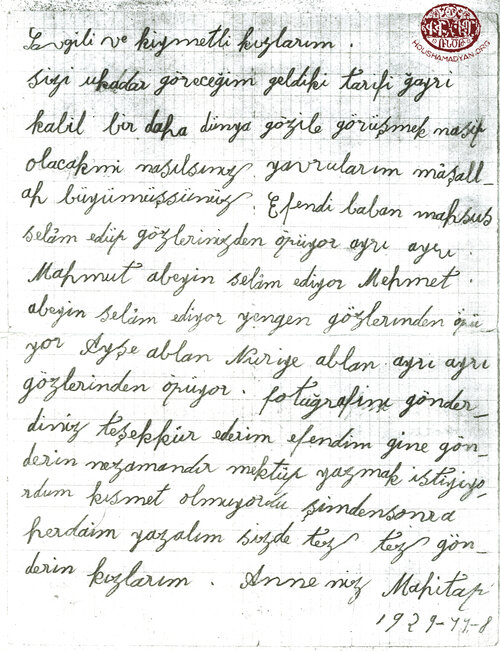

Araksi never forgot, and never could forget, the years that she had spent in the home and under the care of her protector, Mahitab Hanum. Naturally, this woman’s kindness and compassion left a deep impression on her young mind. Despite the upheavals in their lives, Araksi and her adoptive mother regularly corresponded in later years. The excerpt below, from a letter dated 1929, attests to the love that they shared. It shows that this Turkish woman still saw Araksi and Berdjouhi as her own daughters and treated them as such. According to her son, Krikor Kavedjian, Araksi, in her turn, always remembered Mahitap Hanum as her “Turkish mother.”

My dear and dutiful girls,

Words cannot describe how much I miss you. Will I ever have the fortune of seeing you again in this life? How are you, my children? You’re so grown up. Your father, the effendi, sends you his special greetings, and kisses your eyes, one by one. Your older brother Mahmoud sends his greetings. Your older brother Mehmet sends his greetings, and his wife kisses your eyes. Your older sisters, Ayshe and Nouriye, kiss each of your eyes. Thank you for sending me your photograph. Send more photographs. I’ve wanted to write to you for a long time, but I didn’t have the chance. From now on, let’s always write to each other. Write to me often, my daughters.

Your mother, Mahitap,

November 8, 1929

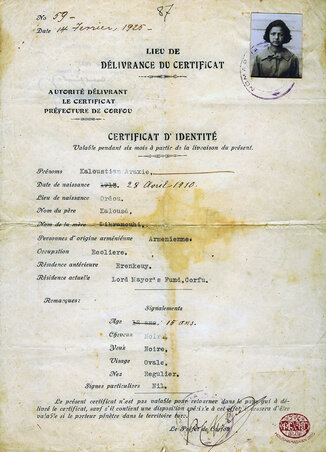

1), 2) Araksi Kalousdian’s identity card, issued on February 14, 1925, by the local authorities of Corfu (Greece). In that year, Araksi used this document to travel from Greece to Marseille.

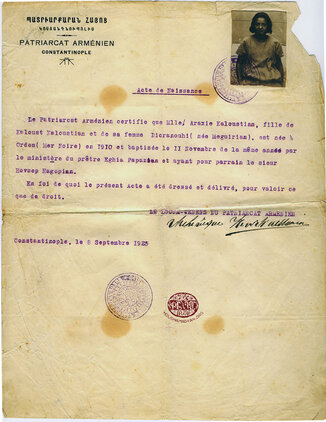

3) Araksi Kalousdian’s birth certificate, issued on September 8, 1925, by the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate and signed by the interim Patriarch, Archbishop Kevork Arslanian. Notably, some of the information in the document is incorrect, namely Araksi’s birth year, father’s name, and mother’s maiden name.

The leaders of the Tbrotsaser School, like their peers in other Armenian orphanages, fervently encouraged their wards to marry fellow Armenians. This gave them the satisfaction of having contributed to the nation’s rebirth, as well as of having helped the orphans find their places in society. They would enquire into potential suitors’ financial standing, health, and moral character, to ensure that they were good matches for their wards. Based on these enquiries, they would give their blessing to the proposed marriages. Most probably, Araksi’s marriage was the result of such a process. Garabed Matos Kavedjian (Kahvedjian), born in Stanos (a city near Ankara), presented himself to the orphanage with members of his family and expressed his desire to marry one of the orphans. The wedding ceremony took place on May 31, 1931, at the Saint Hovhannes Armenian Church on Jean Goujon Street, in the Eight Arrondissement of Paris. The couple were blessed with two children, Krikor (born in 1943) and Denise-Dikranouhi (born in 1946).

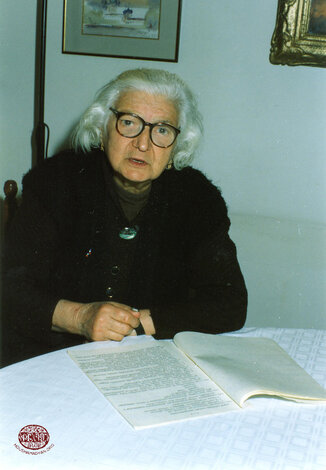

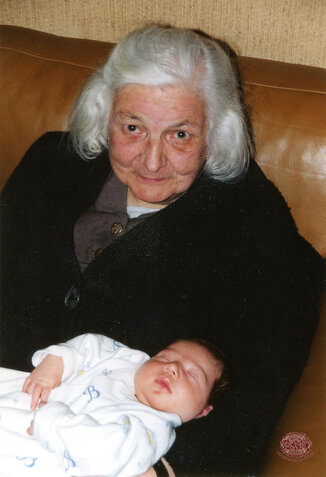

Matos died in 1979. Araksi died in 2003. She was laid to rest in the town cemetery of Issy-Les-Moulineaux – the same commune in which she had lived for 72 years. According to her wishes, Mahitap Hanum’s letter was buried with her. The family kept only a copy of it.