Boghos-Der Bedrossian collection - Los Angeles

From Til to Qamishli: The Boghos Family's Journey

Author: Sevan Boghos-Der Bedrossian, 18/11/2021 (Last modified: 18/11/2021), Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

The Shadakh (Eastern Tigris) and Bohtan rivers, traversing the Eastern Armenian Taurus Mountains, join the Tigris River. It’s here that the village of Til (now Çattepe) is located, a natural barrier to the mighty flowing waters of the Tigris. My grandmother, Hana, was born in this village in 1906. Til is located south of the city of Sghert/Siirt. Due to the Ilısu Dam, built by the Turkish state in this region, present-day Til, as well as many other surrounding villages, are completely submerged. Thus, a whole rich human heritage from the Bronze Age has been destroyed.

During the years of the Ottoman Empire, Hana's grandfather, Bedros Sarko, owned the arable land in the village of Til. Bedros’s daughter and Hana’s mother was Hripsimeh. She was tall, with green eyes and yellow hair. The villagers called her "Sherineh”, which means beautiful in Kurdish.Years later, when the era of massacre and deportation approached, the name "yadeh" (in Kurdish, my mother) would be added to Sherineh's name, because this woman would provide shelter to and serve as a protector to her grandchildren orphaned by poverty, famine and epidemics.

This strong woman, Hripsimeh, lived for 100 years. Yadeh Sherineh was the wife of my great-grandfather, Boghos. All of them were brought up by Protestant missionaries and often read the Bible. Protestant missionaries were active in those areas. Despite the fact that we were Apostolic, the missionaries spread their message everywhere. It was interesting that the Bible kept in my family was written in Kurdish with Armenian letters.

Boghos died in the village of Til before the Genocide. His children are Minas, Vanes, Hanna and Hana. Boghos’s family craft was pottery. They made clay jars and jugs. Due to the geographical location of the village, the inhabitants lived near abundant waters and rivers. All of them were good swimmers. Even my grandmother, Hana, swam well. And thanks to the lands owned by Bedros Sarko, our family was considered rich given the conditions of that period.

I often heard the names of the following villages from my mother- Hazro, Ridvan(Rndvan), Kerboran, Chelik (Chalek). These are villages in the valley of the Tigris River, where my paternal and maternal ancestors roamed from village to village.

We know that during the years of the Genocide, Hripsimeh and her family fled Til and settled in the village of Chelik, on the opposite bank of the Tigris, a little further south, where, for reasons unknown to me, they were safer. My ancestors said that this escape was possible due to Hripsimeh's ingenuity. Most likely, the family’s life was in danger at that time. But Hripsimeh managed to get her young children out of the village one by one and take them to Chelik. Every day, Hripsimeh, with a large copper bucket in her hand, passed in front of the Kurds in her village, without revealing that she was taking food to her children to Chelik. She joined them later.

In Chelik, my grandmother, Hana, matured and became an eye-catching young woman. Hripsimeh and her brothers soon married her off to the only surviving member of a family of 30, the young Soleyman Mksi. Soleyman and his family were from the village of Hazro. During the Genocide, the Kurds killed his brother, kidnapped his aunts Khatoun, Reyhan and Srpouhie, and wounded Soleyman. Soleyman's fourth aunt, Gyulizar, lived with her family in the town of Sghert/Siirt. Gyulizar’s husband was a teacher in the Armenian school of Sghert. In 1915, the Kurds killed him in the city, and Gyulizar and her children were killed while trying to escape.

A twist of good fortune saved Suleyman’s life. The family story is that the Kurds treated his wounds upon learning that Soleyman is a master shoemaker and can make shoes for them. Indeed, Soleyman was a leather craftsman and shoemaker. He’d relate that after these experiences he wanted to flee the area and join the Armenian troops led by Antranig. However, he dared not take this step given his wounded state. He would relate these experiences in his own language and style, stating that a Bolshevik revolution had taken place in Russia so that the Russian emperor could not help the Armenian fedayees (volunteer soldiers).

Afterwards, Suleyman follows the banks of the Tigris to the village of Chelik, where he meets Boghos’ family and marries Hana.

A few years later, in 1923, my grandmother's family and my grandfather fled Chelik, descended to the village of Idil (Azukh, Azakh) further south, and settled there. Like Chelik, Idil was within the borders of the newly formed Turkey and was very close to French-controlled Syria. They built a house, garden and a stable in Idil. But life here is short. In 1925, a Kurdish uprising led by Sheikh Said broke out, which also included these areas. The Turkish armies succeeded in suppressing this revolt, after which the state took serious steps to remove the remnants of the Armenian population from these territories. In 1927, my great uncle Shiukri was born in Idil/Azukh.

The family emigrated from Turkey to Syria during these years. The exact date is unknown. We do know that in the 1930s they were already settling in Ain Diwar, again on the banks of the Tigris River, which was the most northeastern point of French-controlled Syria at the time․ The family builds a new house here, a garden and a stable.

The Ayn al-Askari (Military Spring) was in Ain Diwar. My grandmother would fetch water from there, carrying two tins (tenekeh) of water in one go. She also carried sticks and branches to keep the fireplace burning. She milked cows and goats, and even slaughtered sheep. She used “chvit”, a blue substance especially made for laundry, to whiten the clothes. The bread dough was spread early in the morning, and everyone wanted to eat Hana’s tonir-baked bread. She buried clay jars of cheese in the ground to keep them cool and fresh. Making bulgur was a ceremony. The wheat was boiled in a barrel taller than a man, right in the middle of the intersection of the district. Neighbors would gather and the work would progress with singing, joking, and telling stories. Work turned into fun and people temporarily forgot past worries. My father's mother, Seve, was as lively as Hana. Seve’s songs and sweet voice seemed to complement the musical portion of that vivid scene.

Members of the second generation often related the memoirs of Ain Diwar. My other uncles and father were born there, since my grandmother's brothers also settled there. It is said that the French General Charles de Gaulle visited Ain Diwar in 1944. My middle uncle, Mansour, sang the French national anthem during the flag-raising ceremony. He was given five ghouroush for doing that, but the priest grabbed the money from his hand.

At that time, the Kurds were persecuted in Turkey. Under these conditions, large numbers of Kurds begin to seek refuge in these Syrian towns and villages bordering Turkey. They also settle in Ain Diwar.

Most of my mother's uncles died, one after another, due to epidemics and poor health. Thus, a line of grandchildren was orphaned, whose care was assumed by Hripsimeh. She became the “yadeh”, the mother of all. In 1938, Hripsimeh’s family moved to the town of Qamishli, in the same Syrian area, and settled in the Gharbi (Western) district of the city.

My paternal grandfather, Hanna, was a soldier in the French army. He was also a very good swimmer. Swimming in the Tigris River, he collected the logs that came downstream and sold them. His kidneys were damaged by these frequent cold-water swims, and he died at a young age.

In 1938, my grandmother Hana’s family moved to Derik. My father, Sabri, lost his father at an early age, and his brothers and sister died from epidemics. Sabri did not attend school but worked with his orphaned cousin in the famous "Garbis Cafe" in Qamishli at that time. With help from Hripsimeh, these two orphans established homes and families, and then began to hold simple jobs in state institutions. Hripsimeh and Hana arranged the marriage of my father, Sabri, and my mother, Varti. They were cousins. The wedding took place in 1957, and my mother left Derik for Qamishli as a bride. In 1963, they moved to Damascus because of my father's health problems. I was born there in 1975. My name is Sevan, in memory of my paternal grandmother, Seve. Seve means “apple” in Kurdish. The names of the first and second generation members of our family were often Arabic or Kurdish. But the language spoken in the house was no longer Kurdish, but Arabic, since a large part of the inhabitants of Azukh, Ain Diwar, Derik and Qamishli at that time were Arabic-speaking Syriacs. Later, it was the third generation that was able to attend an Armenian school and communicate in Armenian.

Derik, 1947. Standing, from left - my uncle Shiukri, my uncle Mansour, his cousin Boghos. Standing, from left - my grandfather’s aunt Khatoun, who was abducted by the Kurds during the Genocide. To her right is my uncle’s wife Liona, my grandmother Hana, my uncle Eyoub. The two younger children are the neighbors’ kids.

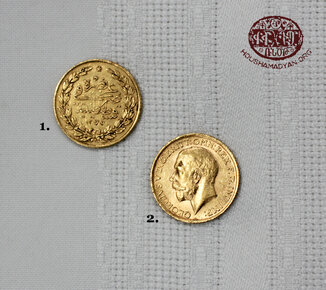

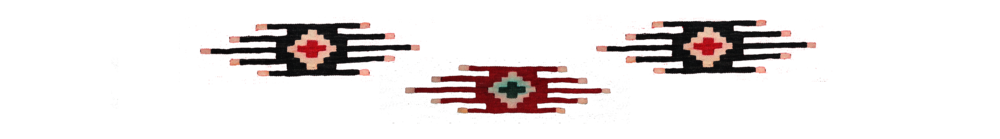

Hripsimeh lived until 1970, when she turned 100 years old. It is said that she kept her natural beauty until the end. I inherited her only photo, her mortar, two copper pots, pans, a few rugs, one mejidehand one English gold piece. The families of Boghos and Mkdis (Soghomonian) are scattered all over the world - Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and the United States, where I am. The youngest member of the Soghomonian (Mkdis) family was born in October 2021 in Derik and was named Khachig.

My grandmother, Hana, died in 1987. She is the only one of the main characters in this family story that I knew personally. As I mentioned, my family lived in different places in Syria. Wherever they settled, they maintained their daily customs and traditions. My grandmother, until her death, wore the yazma(head scarf) and long white undergarments. She had two trunks; one made of wood and the other, copper. She kept her veils and snuff in them. Every day, morning, afternoon and evening, she sang the "Amazing Grace" hymn in Kurdish.

Truly, we were not ashamed of our grandmother at all, nor did we want to change her appearance. She sat in her corner, always praying, weeping and recounting the path of her life, from the village of Til to her last refuge in Derik.

Family of Soleyman and Hana (Derik, 1968). Standing, from left – my uncle Mansour, my uncle Eyub, my grandfather Soleyman and Ablahad, the son of my great uncle Minas. Middle row, seated, from left – my uncle’s wife Majida, my uncle’s wife Nvart, baby Maral (in Majida’s lap), and my grandmother Hana. Front row, from left – Srpouhie, Haig, Hayganoush, Hasmig (in Hana’s lap), Khatoun.