The Near East Foundation’s Collection of Photographs of Armenian Farming Settlements in Syria

Author: Vahé Tachjian, 21/04/21 (Last modified 21/04/21), Translator: Simon Beugekian

The photographs presented on this page are cared for by the Arab Image Foundation and are part of the Nigol Bezjian Collection. The collection consists of 92 paper prints. About 80 pictures are displayed here pertaining to the work of the Near East Foundation (NEF) in the early 1930s.

Nigol Bezjian obtained this collection in Beirut. It was originally kept in the care of Reverend Dikran Kherlopian. After the latter’s death, a relative inherited the collection, and then gifted it to Nigol Bezjian.

Near East Relief (NER) was an American organization founded immediately after the end of the First World War. Beginning in 1931, the organization was known as Near East Foundation (NEF). NER was the successor to a network of American missionaries who had engaged in wide-ranging religious and humanitarian work in the Ottoman Empire. In the post-war era, the focus of NER’s work was the provision of aid to Armenian refugees and orphans. As a result of the Armenian Genocide, many thousands of Armenians had been left homeless, living precarious and unsafe lives in refugee camps. Alongside them lived tens of thousands of Armenian orphans deprived of basic care.

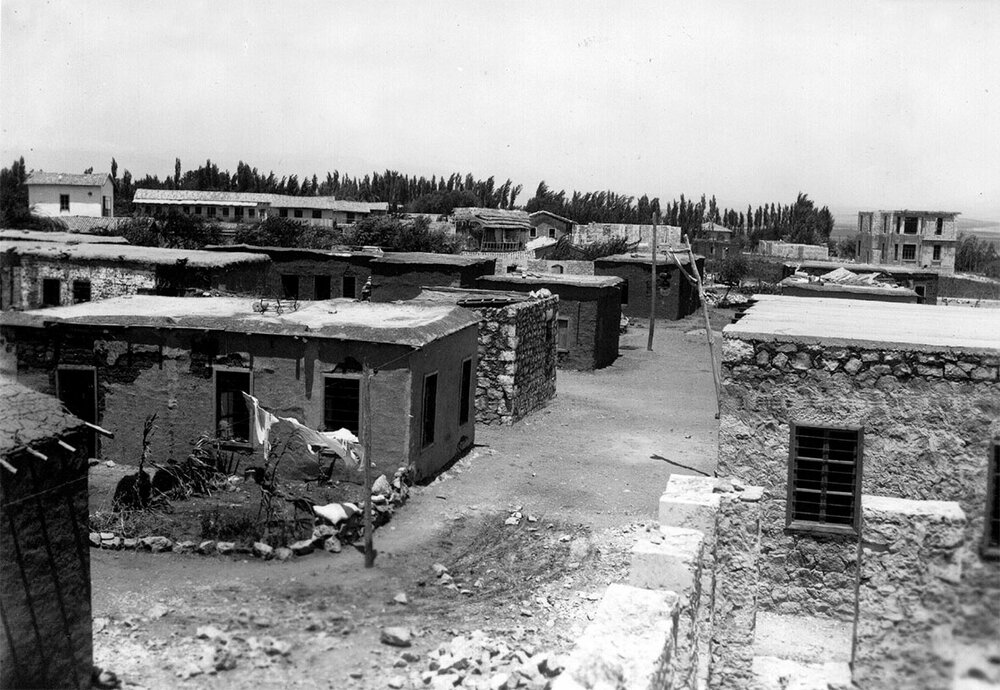

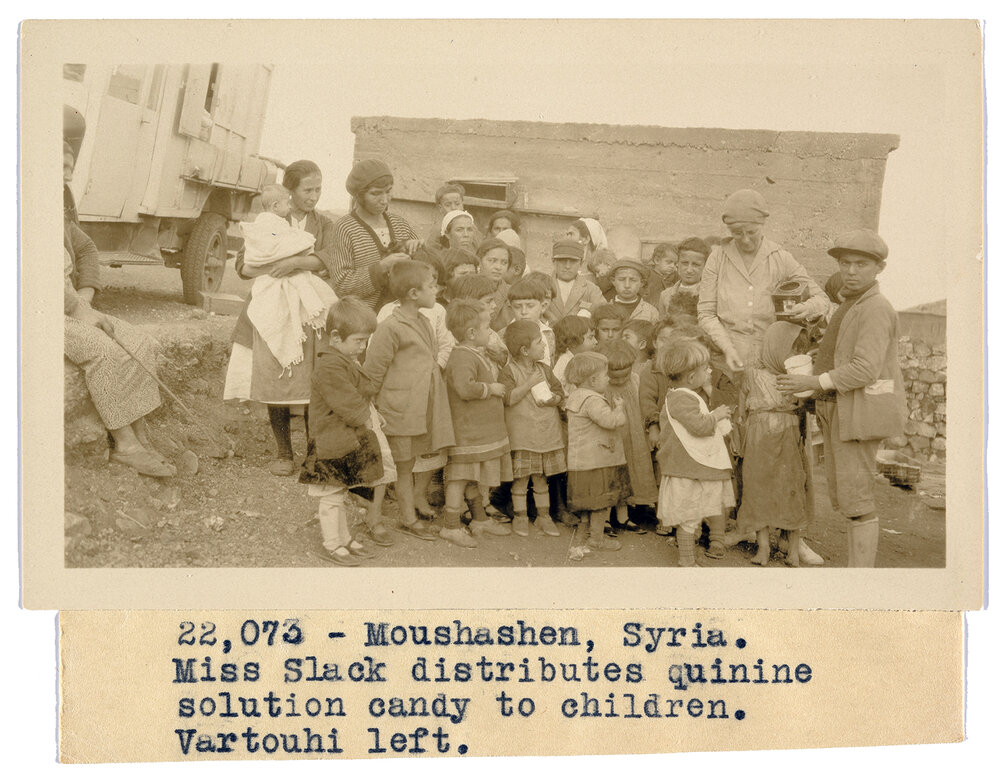

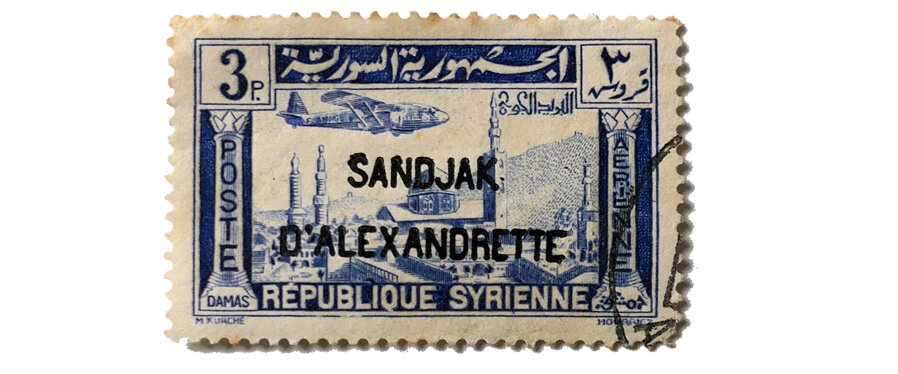

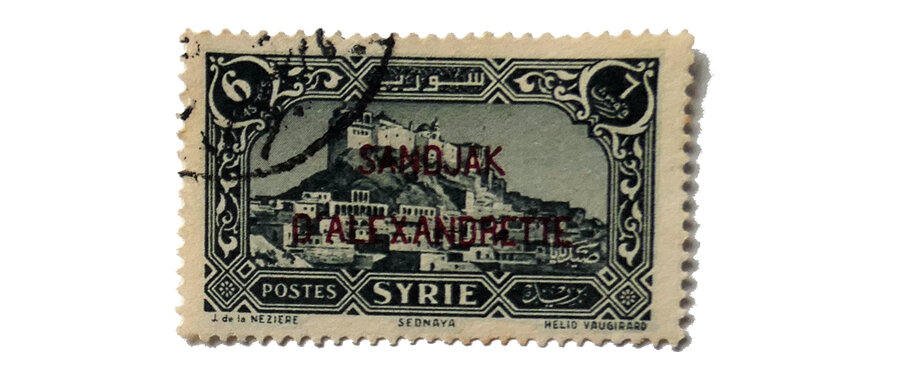

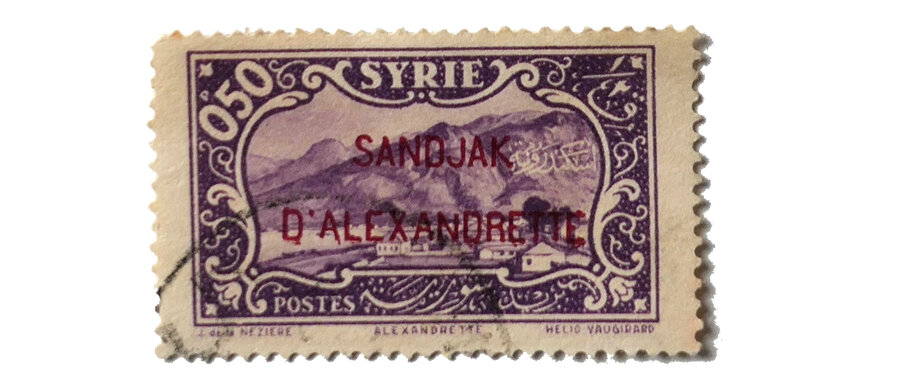

The photographs in this collection document the work of the NEF. Many were taken during regular visits made by the NEF medical team to Armenian villages in Syria. For the team headquartered in Aleppo, these visits mostly focused on two specific areas. The first was Antioch, including the villages of Hayashen (present-day Cumhuriyet), Abdal Houyouk (present-day Üçtepe), Rihanie (present-day Reyhanlı), Yeni Shehir (present-day Yenişehir), and Sichanli/Sıçanlı (the last a village not populated by Armenians). We must note that at the time, Antioch, or the sandjak of Alexandretta, was part of the French Mandate of Syria, and remained so until 1939 when it was ceded to Turkey. The second primary destination of these visits was the area of Masyaf, namely the villages of Moushashen (present-day Mushashin) and Jubb Ramlah, west of the city of Hama.

So how did Armenians come to live in these villages?

The Deportation of Armenians from Turkey and Efforts of Resettlement

The flow of Armenian refugees into Syria during the years of the First World War and immediately afterward can be divided into two main stages:

1) During the years of the Genocide, hundreds of thousands of Armenians were deported from their homelands and driven into Syria, specifically towards Aleppo, Hama, Homs, Der Zor, Damascus, Raqqah, and surrounding villages. As we know, a significant percentage of these deportees were subjected to massacres along the way or fell victim to epidemics. The survivors continued living in the cities that they had reached until the occupation of Syria by Allied (mostly British) forces. After taking over the area, the Allied authorities launched efforts to resettle these refugees back in their native lands. Specifically, refugees were resettled in Cilicia, including the province of Adana; as well as cities further east, including Marash, Ayntab, and Ourfa. During this time, control of Cilicia was transferred to the French forces. By that point, Syrian cities no longer had a significant Armenian refugee population.

2) The second wave of Armenian migration into Syria began at the end of 1921, when French forces began retreating from Cilicia and ceded the area to the Turkish government. Prior to the entry of Turkish forces into the area, a mass exodus of Armenians began towards Syria and Lebanon. These new arrivals mostly settled in hastily constructed refugee camps in large cities, including Aleppo, Beirut, Damascus, and Iskenderun/Alexandretta. Tens of thousands of Armenian refugees once again began a new life in the Levant.

The French Mandate authorities of Syria, after some initial hesitation, decided to directly support initiatives that aimed to free these Armenians of their status as refugees and to encourage their permanent settlement across Lebanon and Syria.

Predictably, the unstable and unsafe life of refugees drove many of these Armenians out of the region. And so, throughout the 1920s, a large number of Armenians left Lebanon and Syria for South America, especially Argentina and Brazil. By now, the immigration of large numbers of Armenians into Soviet Armenian from other parts of the world had begun, and it proceeded through the 1920s and especially the 1930s. But the French authorities were opposed to the mass migration of Armenians from areas under their control to Soviet Armenia.

To keep Armenians in the Levant, it became imperative for the French Mandate authorities to implement programs to encourage their permanent settlement. It took until 1926 to finally bring the settlement programs run by various organizations under one umbrella, and to proceed to action. Among the entities leading these efforts were the High Commissioner for Refugees of the League of Nations, the Syrian and Lebanese authorities, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU).

Among the most important settlement projects was the construction of new Armenian neighborhoods in Beirut and Aleppo, where Armenian refugees would live. Work on these projects began in the late 1920s. Various Armenian compatriotic organizations made important contributions to these efforts, making use of their vast international networks to secure the financial support needed for an effort of such scale.

Another one of these settlement projects, although much smaller in scale, was the creation of new Armenian farming settlements across Syria.

The Creation of Armenian Farming Settlements across Syria

Armenian settlements had existed in the Antioch region since ancient times, including the villages of Mousa Ler, Beylan (Belen), and Kirikkhan (Kırıkhan). For this reason, the area was considered suitable for new Armenian farming settlements. Concurrently, many refugees were settled in the existing farming communities of Beylan and Kirikkhan.

These efforts were coordinated on the ground by Georges Burnier, the Swiss representative of the League of Nations in Syria and Lebanon. He was also the general secretary of the League’s Office of the High Commissioner on Refugees. At the time, this office was led by High Commissioner Fridtjof Nansen, the Norwegian diplomat and explorer. Beginning in the 1930s, after his death, the High Commissioner’s Office was renamed the Nansen Office in his honor. Burnier quickly gained the trust of the French Mandate authorities and became a principal figure guiding the work of refugee resettlement. Burnier also had his own trusted local associate in Antioch, namely Movses Der Kalousdian, a member of the Syrian Parliament.

The efforts to create new farming communities in Antioch immediately ran into serious challenges. Among these were the poor climate, the prevalence of malaria (especially in the Amuk/Amik Valley) and other diseases, as well as the international economic crisis. As a result, the settlers faced terrible economic conditions. Many of them soon left to seek better lives elsewhere.

Below, we present a list of the Armenian farming settlements that were established in Antioch beginning in the late 1920s.

Abdal Houyouk/Üçtepe: In Armenian sources, this settlement is also called Vartsahen. It was founded in 1928, and was located between Aleppo and Antioch. French sources mention that the settlement was created in an area commonly known as pré militaire (“military field/prairie”). During the Ottoman era, a Turkish cavalry regiment had been stationed there. After the settlement of Armenians, a school was opened in the settlement, as well as a clinic operated by the NEF.

Hayashen/Cumhuriyet: Sources also call this settlement Asger Chayir, Haygashen, and Norshen. Like Abdal Houyouk, it was founded in 1928, again in the area previously known as pré militaire. During the Ottoman era, the settlement had been inhabited by Circassian refugees, many of whom had died of malaria. As a result, it had been abandoned. The threat of malaria was still significant at the time of the settlement of Armenians. Efforts were made to drain the nearby swamps, eucalyptus trees were planted, and the NEF medical team visited frequently. The settlement was home to a school, as well as an NEF-administered clinic. Many of the refugees who settled down in Hayashen came from the villages of Kharpert/Harput.

Rihanie/Reyhanlı: Located between Aleppo and Antioch.

Yeni Shehir/Yenişehir: Located between Aleppo and Antioch.

Soouksou/Kurtlusoğuksu: This settlement is called Sovouk Sou in Armenian sources. It was founded in 1928 and was located south of Iskenderun and west of Kirikkhan, in the Amuk/Amik Valley. Most of the settlers were Armenian refugees from Deortyol/Dörtyol. The residents of this settlement were under the special care of Friends of Armenia, a British organization. Soouksou had its own school, and received frequent visits from French Red Cross medical teams that provided medical care to the residents. Many Armenians who lived in Aleppo owned summer homes here. Among other residents of Aleppo who spent their summers in Soouksou was Karen Jeppe, the celebrated Danish missionary.

Nargizlik/Nergizlik: This settlement was located south of Iskenderun, in the Amuk Valley. An Armenian school operated in the settlement.

Sooukolouk/Güzelyalı: In Armenians sources, this settlement is called Sovouk Olouk. It was located south of Iskenderun, in the Amuk Valley. It had its own Armenian school. Like Soouksou,it was a popular holiday destination for Aleppo Armenians. Numerous families would come to the village to spend the summer months.

New Zeytun: Historical sources also call this settlement Ekiz Keopru. It was located very close to the villages of Mousa Ler/Musa Dagh, north of the village of Bitias. The present-day name of the village is unknown. It was called “New Zeytun” simply because it was home to many resettled refugees from Zeytun. It was founded in 1927. A team from the French Red Cross made regular visits to the village to provide medical care to the residents. The village also had its own school.

Bey Seki/Gözcüler: The settlement was founded in 1930, near the coastal city of Arsuz.

The League of Nations also sponsored the establishment of one Armenian farming settlement outside of Antioch. It was called Moushashen (present-day Mushashin), located in the region of Masyaf, west of the city of Hama. Were the majority of this settlement’s residents refugees from Moush? And is that why the village was called Moushashen? We could not answer this question definitively. The NEF operated a clinic in the village, which also had its own Armenian school, the Lousinian School.

Additional farming settlements were founded across Syria beginning in the 1920s, many of which were created thanks to the efforts of Danish missionary Karen Jeppe. She was the League of Nations’ Commissioner for the Protection of Women and Girls in the Near East. These communities were created in northern Syria, on the eastern shore of the Euphrates River, to the north and north-east of the city of Raqqah. The construction of these settlements was not sponsored by the League of Nations. In the 1930s, more Armenian communities were founded in the areas of Kamishli and Hasake.

The NEF Photographic Collection: Humanitarianism and Orientalism

As we have noted, the newly created Armenian farming settlements in Antioch immediately faced serious medical crises, chief among which was malaria. Beginning in 1929, these settlements were frequent destinations of visits by NEF and the French Red Cross staff or medical teams. Aside from routine medical examinations and care, these teams also distributed quinine and mosquito nets to the local population and helped drain the area’s swamps. These efforts were aimed at combatting the spread of malaria.

The photographer of this collection remains unidentified. Presumably, s(he) was a member of the NEF team who had a photographic device, which s(he) used to take the 92 photographs on various occasions. We also do not know the identity of the author of the captions that accompany the photographs. Most probably, the photographer and the author of the captions were one and the same – an American member of the NEF team.

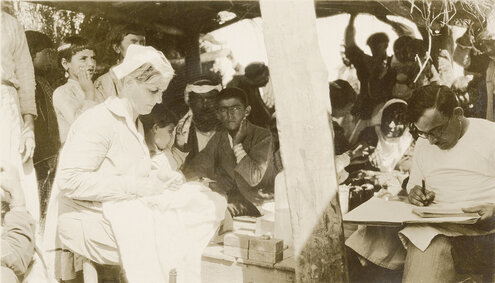

The principal aim of the NEF team was the provision of medical care to the residents of the newly founded Armenian settlements. But they also used the opportunity to visit nearby non-Armenian villages. The photographs have recorded a visit by the NEF truck to the village of Jubb Ramlah. In the photograph, the vehicle is surrounded by villages receiving medical treatment. In total, the NEF team was responsible for eight villages and settlements, both Armenian and non-Armenian. Their frequent visits to these villages allowed the photographer to document life in non-Armenian villages, as well.

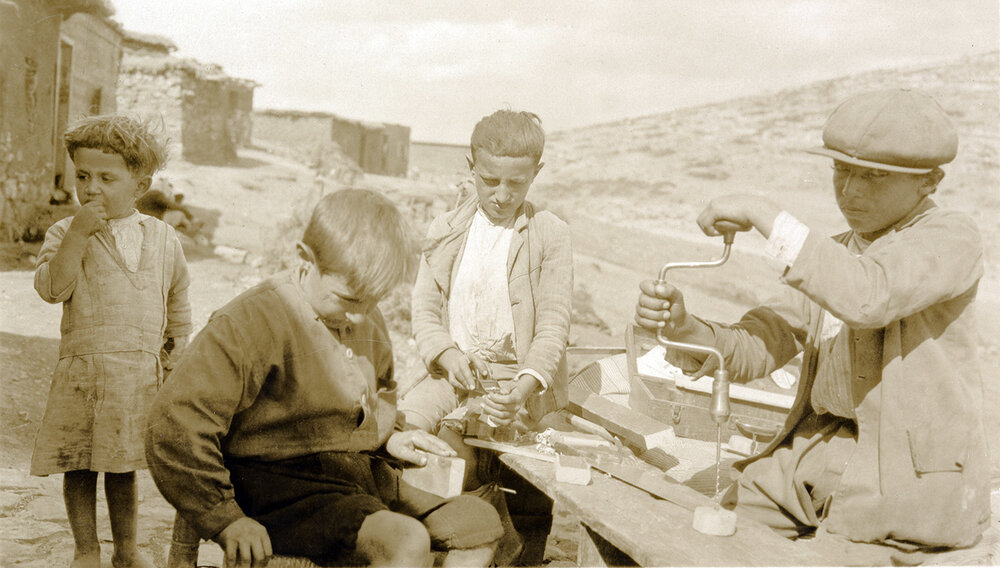

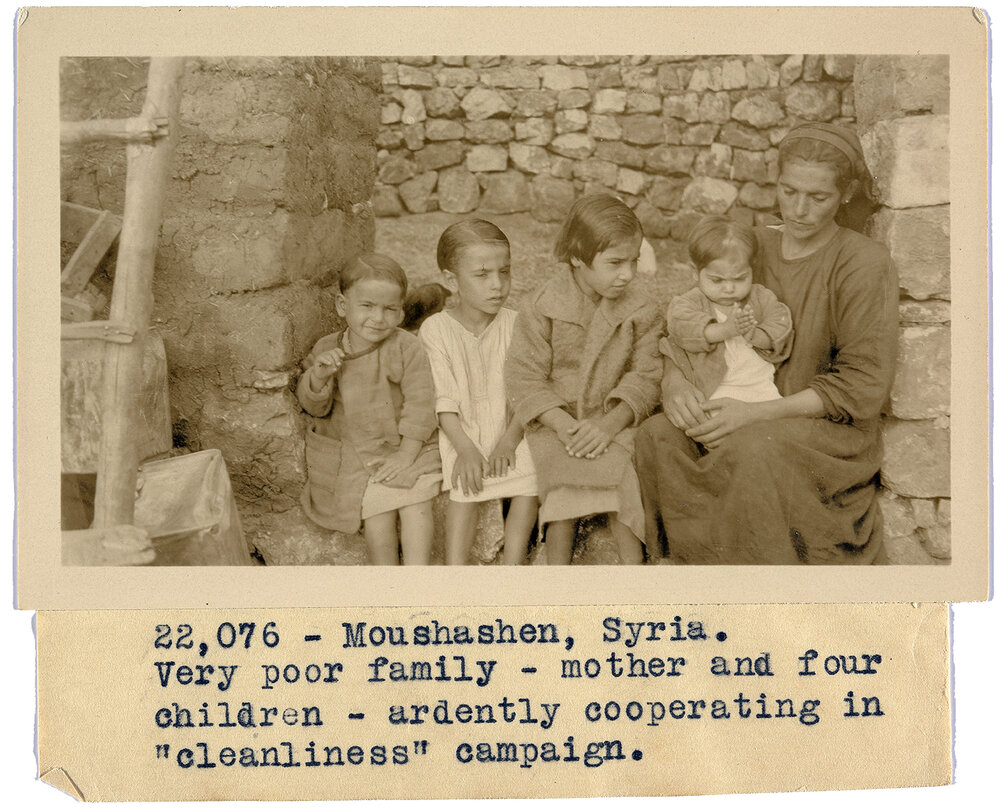

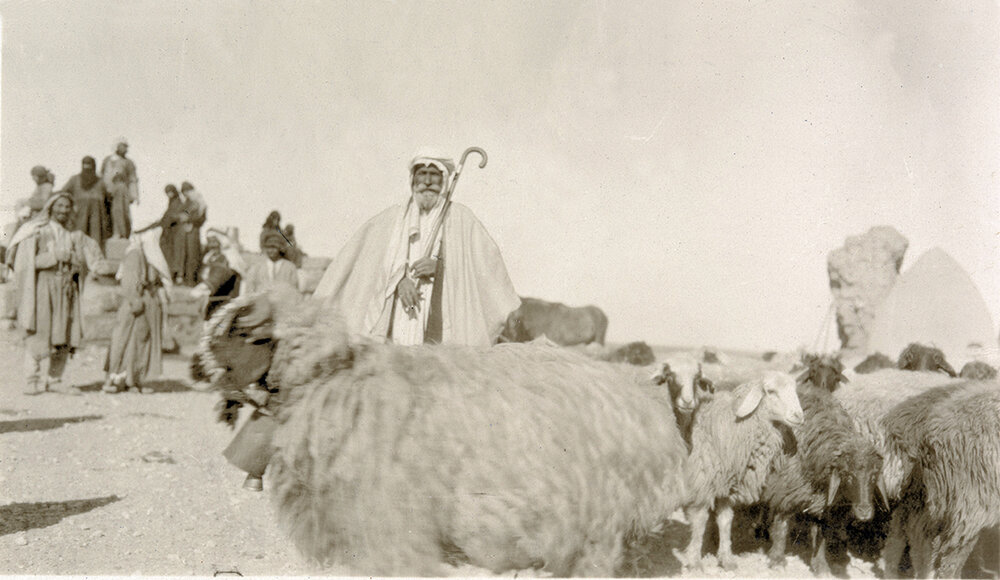

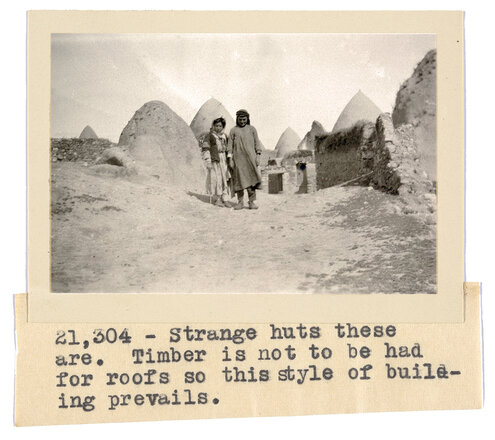

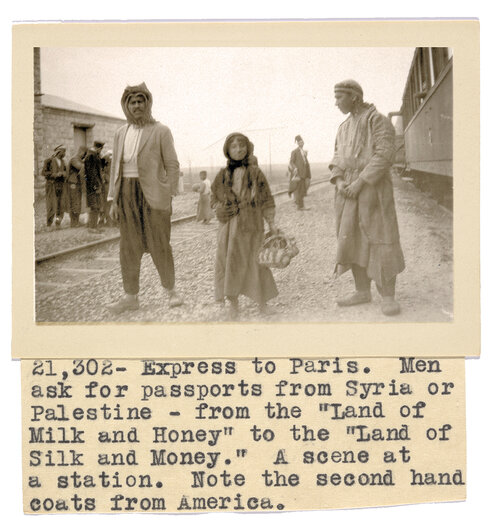

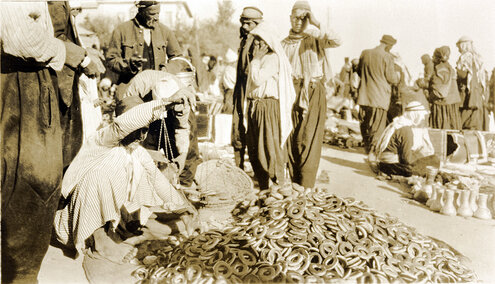

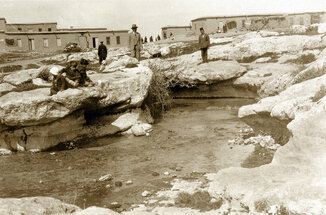

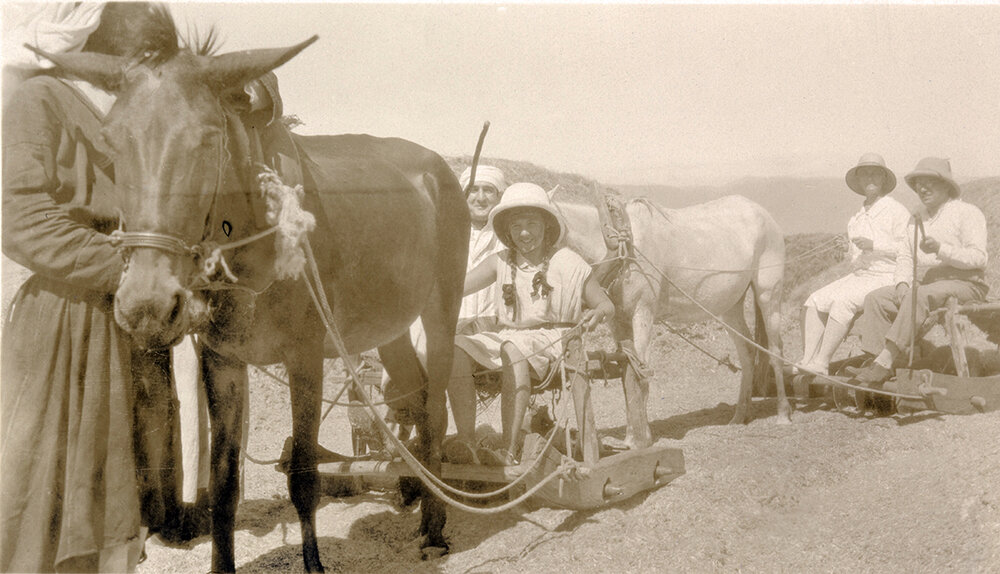

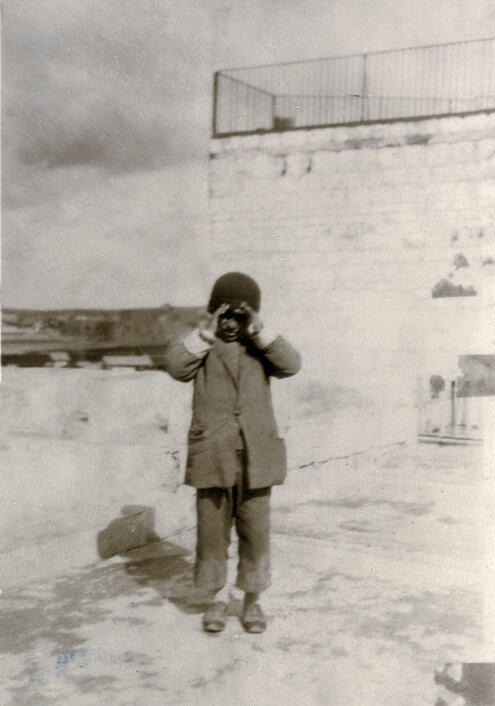

Many of the photographs feature scenes from the villagers’ daily lives, giving us a glimpse into their world. They show villagers ploughing their fields with their animals; the threshing of grain with threshing boards; the grazing of sheep and goats; the baking of bread in tonirs; the installation of a new tonir into the ground; the pulling of water out of a well; the blacksmiths at work; the grinding of grain in a stone mortar; the open-air market of a village; and an open-air barber at work. The photographer also attempted to immortalize some of the more joyous occasions of village life, such as the games and dances of the children and teens; performances by musicians; intimate and peaceful family moments; and school life.

A significant portion of the photographs pertain to NEF’s work. For example, we see NEF workers distributing quinine disguised as sweets to local children; trachoma examinations; an NEF truck surrounded by locals receiving medical care, medication, and other assistance; Miss Slack’s home visits; the planting of trees by the village schoolchildren; the draining of swamps (part of the NEF’s anti-malaria campaign); and the NEF’s local headquarters. According to one of the captions (0170be00024) that accompany the photographs, the NEF team also held lectures, using visual aids, to educate local villagers on the importance of the anti-malaria campaign and the various methods of prevention.

There are also many photographs in the collection that capture the NEF team in unguarded moments. For example, one photograph shows NEF workers sitting on rocks in a village or a nearby field, having a meal. These photographs allow us to identify the members of the team. The most prominently photographed individual is Miss Annie Slack, an American nurse who was most probably the leader of the regional team. At the time, she lived in Aleppo, where the NEF headquarters was located. We know that during her visits to the settlements, she was assisted by five female nurses, three of whom were former Armenian orphans. The photographs also feature others alongside Miss Slack, some of whom are identified in the captions. Among them is Dr. Hagop Kasabian, the only doctor on the team. A woman named Vartouhi is mentioned, and we see her distributing medication to children. She was probably one of the orphaned Armenians who assisted Miss Slack. Georges Burnier appears in one photograph. He was, as we have already mentioned, in charge of coordinating the resettlement of Armenian refugees on behalf of the League of Nations.

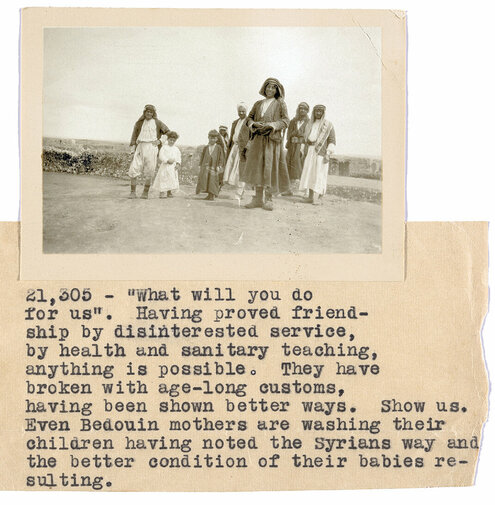

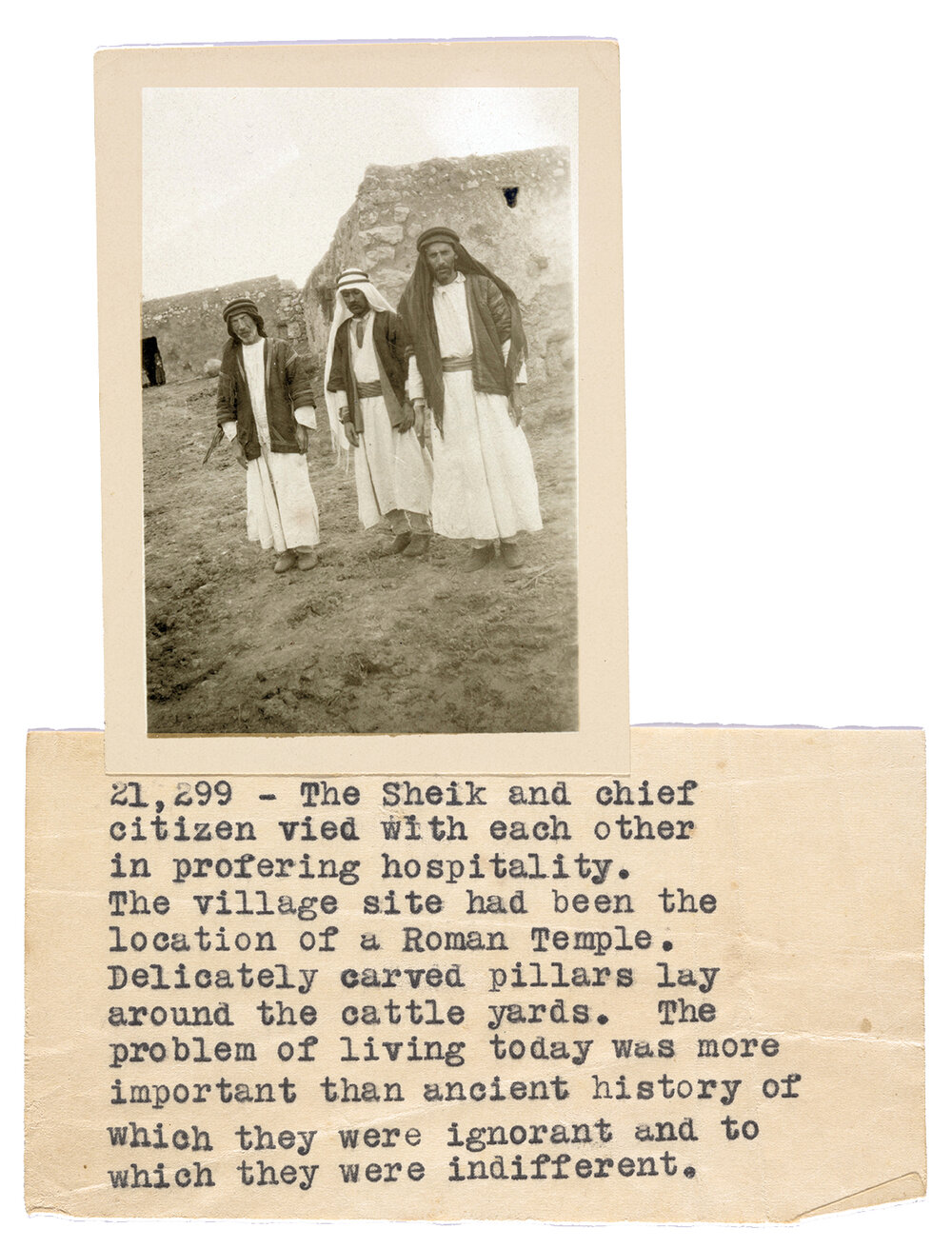

Clearly, the photographer was also intrigued by local “idiosyncrasies.” The photographs feature caravans of camels, villagers in Bedouin attire, traditional farming tools, traditional earthen homes built in the beehive style, local musical instruments, etc. When we carefully examine the captions that accompany these photographs, we can clearly detect the NEF’s (most probably) American worker’s “civilized,” western approach to the idyllic and “backwards” life in the Near East. For example, when (s)he comes across an Arab village in an area scattered with Roman ruins, her/his first thought is not that the village has existed since antiquity. Instead, (s)he comments on the locals’ lack of cultural values: “The problem of living today [for the locals] was more important than ancient history of which they were ignorant and to which they were indifferent.” (0170be00018).

The author of the captions was also convinced that the mission of the NEF team went beyond simple humanitarianism, and that it included the task of bringing light and civilization to these “backwards” parts of the world. We see this when (s)he praises the NEF’s success in convincing the locals to “[break] with local customs” and in teaching them improved medical practices: “Even Bedouin mothers are washing their children” (0170be00022). This attitude of a savior and civilizer is clear in another caption, pertaining to a photograph of a mother and her child. The child is dressed in regular clothing, but the caption states that he had previously been in swaddling clothes – still a common practice today for newborns in many parts of the world. But in the caption, the author implies that NEF members had saved the child’s life by convincing the mother to give up swaddling clothes (0170be00057). This same paternalism takes on a more comical quality in the caption of the photograph showing the locals playing football, which claims that they were taught the game by members of the NEF.

Most of the photographs on this page are presented without their original captions. We made an exception in the case of captions that clearly reflect the author’s attitudes and approach to the NEF’s mission, local conditions, and local population. These captions are of historical value, and we have provided them in their original English. To view the Nigol Bezjian collection with their original captions, please visit the Arab Image Foundation website.

Several photographs that are not part of the AIF/NEF-Nigol Bezjian collection

The photographs in this section are not part of the AIF/NEF-Nigol Bezjian collection, but we decided to provide them on this page in view of their historical value and relevance to the collection.

Photography

- 0170be - Nigol Bezjian Collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut.

Bibliography

- Michel Paboudjian, “Les Arméniens du Sandjak : du génocide à l’exode” [“The Armenians of Sandjak: from genocide to exodus”], from R. Kévorkian, L. Nordiguian, V. Tachjian, Les Arméniens, 1917-1939 : La quête d’un refuge [The Armenians, 1917-1939: The Quest for a Refuge], University of Saint Joseph Press, Beirut, 2006, pp. 146-183.

- T. H. Greenshields, The Settlement of Armenian Refugees in Syria and Lebanon, 1915-1939, Ph.D. thesis, University of Durham (Great Britain), 1978.

- Vahé Tachjian, “Des camps de réfugiés aux quartiers urbains: processus et enjeux” [“Refugee camps in urban settings: processes and stakes,” from R. Kévorkian, L. Nordiguian, V. Tachjian, Les Arméniens, 1917-1939 : La quête d’un refuge, University of Saint Joseph Press, Beirut, 2006, pp. 112-145.

- Hagop Cholakian, Karen Jeppe. Hay Koghkotayin yev Veradznountin hed [Karen Jeppe: alongside the Armenian Calvary and Renaissance], Arevelk Press, Aleppo, 2001.

- Hagop Cholakian, “Hay verabroghnerou deghapashkhoumu yev grtagan kordzi gazmagerboumn ou tbrotsneru Souryo mech (1918-1946)” [“The settlement of Armenian refugees, the coordination of Armenian educational efforts, and Armenian schools in Syria (1918-1946),” Souryo Hayeru [The Armenians of Syria], Antranig Dakesian (ed.), Haigazian University/Center for Armenian Diasporan Studies, Beirut, 2018.

- https://nisanyanmap.com

- Photographic archives of the AGBU, Nubarian Library, Paris.