Semonian Collection - Boxford, Massachusetts

Author: David D'Apice, 12/11/20 (Last modified 12/11/20)

This is the story of my Armenian family.

My mother’s side of the family is one hundred percent Armenian. Most of her relatives were either immigrants to America or first-generation Americans. I fondly remember meeting older relatives with thick accents, scars, and appearances that unmistakably marked them as Armenians. They were resilient, incredibly proud of their heritage, and dedicated to the old-world values of family, faith, and courage. We heard countless stories of the atrocities they had witnessed, alongside episodes of courage. They shared recollections of places long-gone, and of people who celebrated their culture and did everything they could to ensure that their names weren’t lost to time. While my mother’s father’s family, the Aroians, boasted a noble and respected lineage in Kharpert/Harpout, it was my mother’s mother’s family, the Semonians, who bequeathed their traditions and stories to the generations that succeeded them. These are but a few snapshots of our history that stand out in my own mind now that the old-timers are gone and I am left to preserve our legacy.

One of the earliest of our Semonian ancestors was Simon. He was known only by that one name. He lived in the city of Kharpert/ Harpout, and no photographs of him have survived. During Simon’s lifetime, it became apparent that his family would soon face great economic, political, and spiritual upheavals. His wife, Rose (Vartouhi in Armenian), outlived him by many years – she was about 75 years old when she died. She practiced medicine using herbs and spices, something she had learned during her childhood. She lived with her sons and their families, and her skills were noted throughout the city. Once, during Easter, my great-grandfather’s cousin Nishan fell from the roof of the house. During the Easter holiday, it was customary for the local children to place a basket of sweets on the edge of the flat roof, then run backwards to this basket from the other side of the roof and grab the treats. Uncle Nish (as we always called him) won the contest that year, but also went straight over the edge of the roof, landing on the ground below. He broke several bones. The old woman came out and ordered her son to slaughter a lamb and bring the animal’s body to the site. They gutted the lamb and placed Nishan inside its skeletal system after Rose had set his bones. She covered him with herbs and medicines, and bound the entire “body cast” with twine. He was unable to move and remained in that shell for some time until his bones had healed. He later remembered the horrible stench of the carcass. In his later years, after he had lived into his 90s in Lexington, Massachusetts, he again took a fall. When he was rushed to the hospital, the doctors were amazed when they studied his x-rays. They knew immediately that many of his bones had been broken in the past, and they also noted that, without any form of x-ray, they had been reset in their original places with precision. They were astounded to learn about the accident, which Uncle Nishan recounted to them. Rose had done her best work – after all, Nishan was her grandson.

Our family lore includes accounts of attacks by Turkish and Kurdish mobs on Armenians in the area of Kharpert. These events most probably occurred in 1895, during the Hamidian massacres of the Armenians. Rose wasn’t content sheltering from the violence, and she decided that she could help by baking bread for those who were in danger. Her family insisted she remain safely at home, but during the night, she crept away to get to the scene of the fighting. It is said that she was killed during this period of time. Some believe she died of fright caused by the tumult around her. Her photograph was always hanging over the mantelpiece at my great-grandfather’s home. His grandmother was a heroine of the family.

As a young woman, Rose had a son named Mesrob. He was sometimes called Marsoub, Marsoop, or Marshall (the Americanized version). Marshall was born about 1858 in Kharpert. He came from a long line of leather workers and shoemakers, and he took up the family trade early on. When he was about 20 years old, he married Eghsa (Elizabeth) Danielian. Eghsa’s parents were Daniel Danielian and Ruth (Agapeth) Danielian.

My older uncles called Daniel “Danou deh-deh”. For their wedding, the local blacksmith made Marshall and Elizabeth Semonian a small tankard, made of hand-hammered copper and tin, with a lid and a primitive handle. I remember seeing that tankard. Elizabeth typically used it to go to the river and wash clothes. She kept a small rag and a cake of soap in it to use for this chore. I also remember seeing the amber Turkish prayer beads that Marshall had. The beads were a dark orange with caramel-colored pits, and had been worn smooth by his hands until they shone with a rich luster.

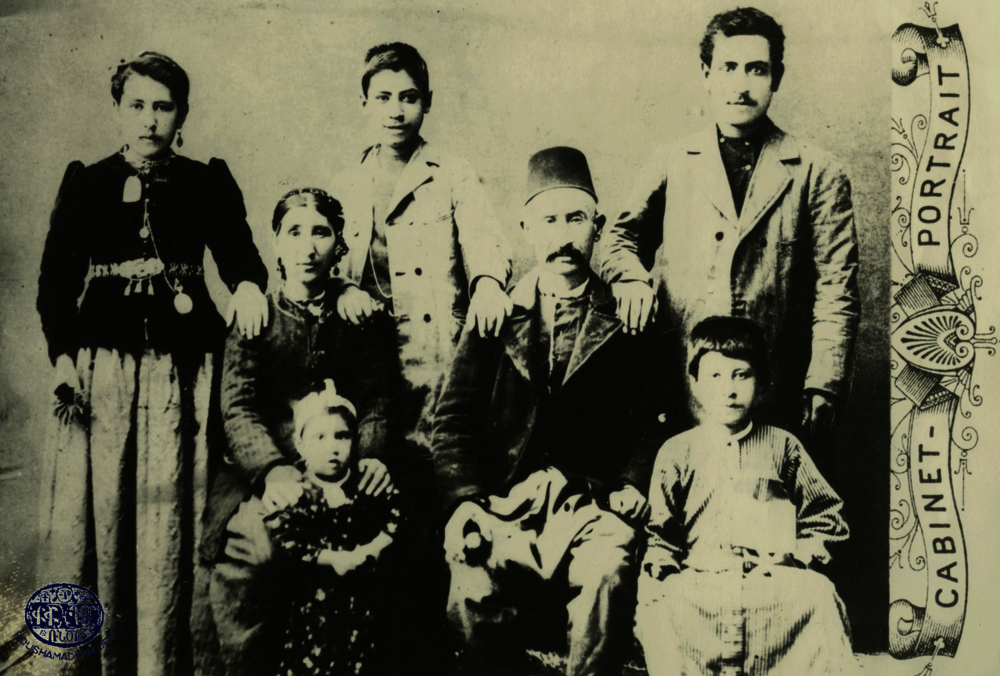

In the early 1880s, Elizabeth had her first child, Mariam. Shortly thereafter, she had three more children: Bedros (Peter), Mardiros (Martin), and Toros (Thomas). The records do not agree on Peter’s exact date of birth. Family history says that he was born with the lambs that year, and that he was premature, but no written records have survived. Elizabeth was a shepherdess, and she carried Peter in a sack on her back while she tended to the sheep. Today, we still have the cup that the local blacksmith made for Peter – it is inscribed “Bedros Mesrobian, 1886 May 29”

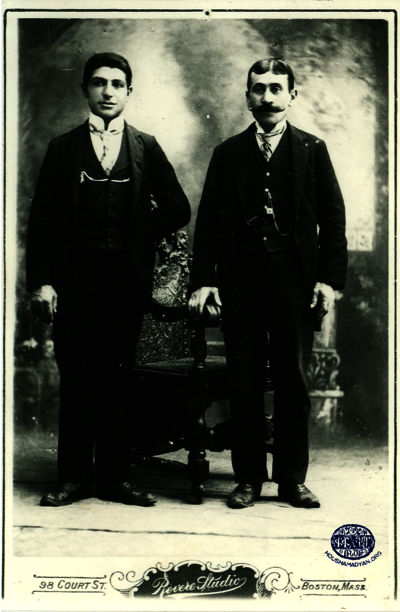

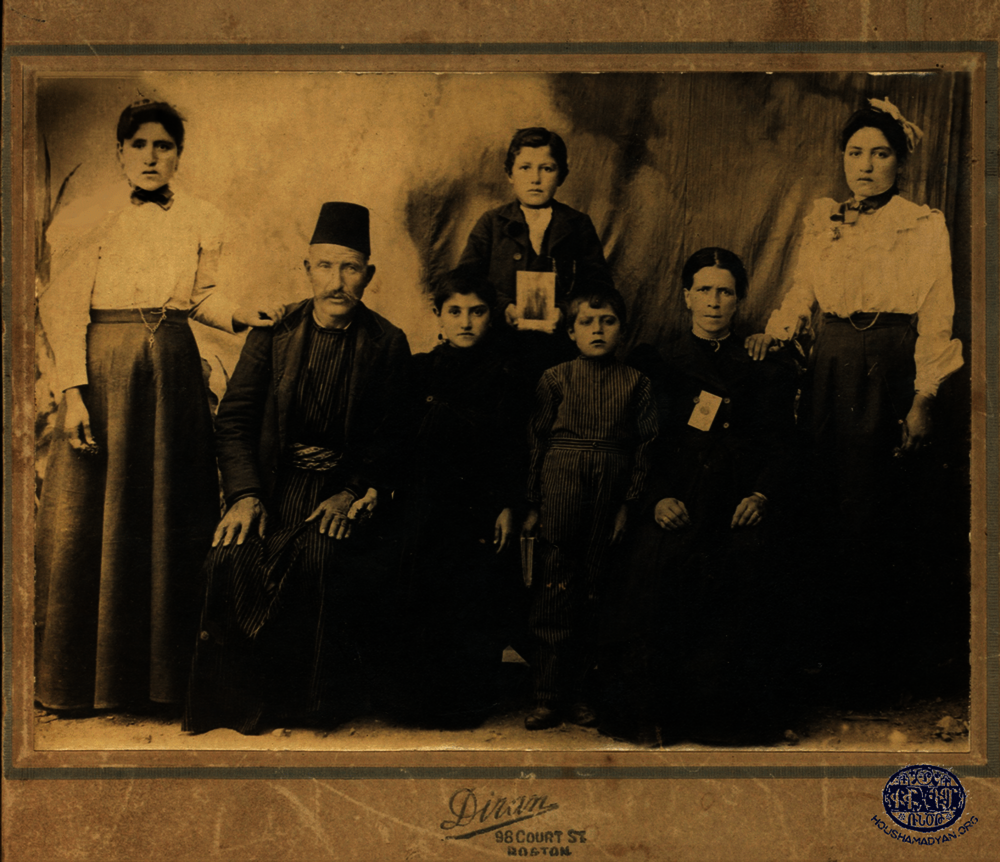

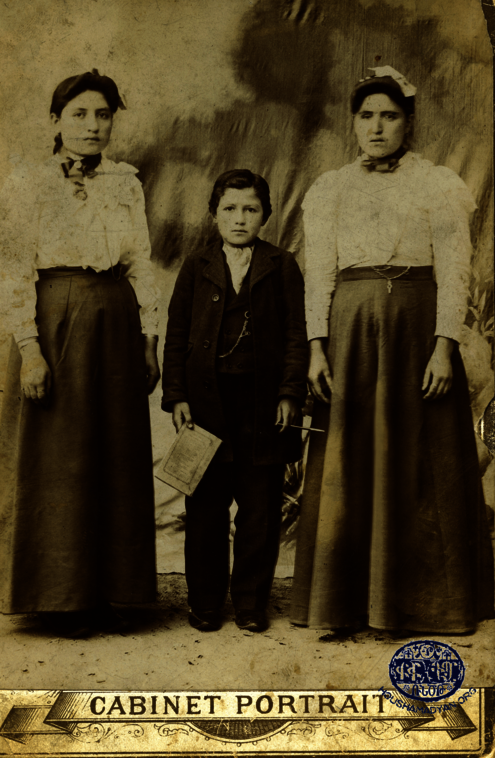

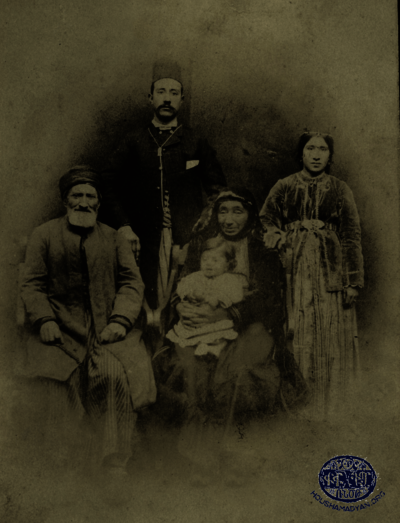

It’s possible that Peter’s age was later changed so that he could gain entry into the United States to work and earn money. Marshall left for America around 1890. He was already in America with a friend when the Semonian family photograph was taken in Kharpert. It may have been the only keepsake he had of his family.

Family history tells us that Peter, when he was about 14 years old, decided to leave the old country. He eventually made his way to a port on the Black Sea. The trip to the sea was by camel caravan and lasted about two weeks. He traveled with everything he had, and he planned to reach New York, join his father there, travel to Massachusetts, and get a job in the Hood rubber mill in Malden, where Marshall himself was employed making heels for shoes. And so, with great hopes, Peter boarded the ship. But at some point, he was hit over the head and thrown into the hold. Based on his account, Turks had been running the ship, promising passage to America, using this as a lure to capture Armenians, rob them, and throw them overboard. At some point, the harbormaster had gotten wind of the scheme, and ordered the ship to return to port. Peter was found, along with many others, and rescued. It took him a while before he was healthy enough to make another journey, and meanwhile, he hid in the attic of a monastery where the nuns kept him out of sight. Eventually, he did make it safely to Marseilles, France, the logical half-way point to America. He stayed there for some time, and learned to speak some French.

He arrived the United States in 1899 or 1900. He managed to locate Marshall, who was living in a boarding house with two roommates at 56 Adams Street in Malden, Massachusetts. The boarding house was within walking distance to the mill, and Peter started working there. Together, the two saved their money for three years, until they were able to pay for the passage of Elizabeth and the three children.

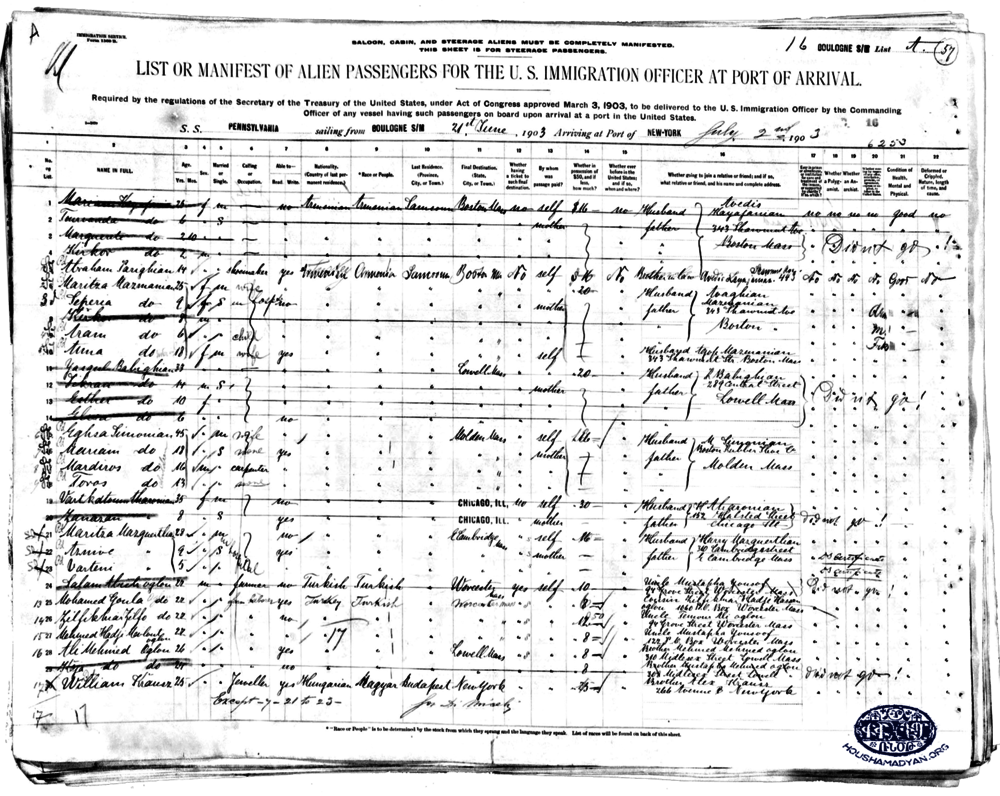

Elizabeth and the children arrived in New York harbor on the SS Pennsylvania on July 2, 1903.

Elizabeth always said that they had alighted from the ship at Castle Garden, and for years, it was thought she was talking about Castle Island in Boston. Actually, even though she was in her 90s, her memory was not failing her – it was in fact Castle Garden in New York where they had landed.

Because it was the end of the week, it took some time for the family’s documents to be processed. By the end of the day on Friday, they were still waiting for immigration clearance and transportation. They had to camp out along the edge of the water, where there were public gardens and lawns. These were quite pleasant, although crowded. On the weekend, there was a fireworks show over the harbor, and the Semonians, mother and three children, felt thrilled that they had made it safely. They thought that the celebration was being held especially for them. As yet, they didn’t understand what July 4th meant to the Americans.

Dressed as they were in Armenian garb, they were immediately aware of how different they looked from the locals. One of the first things young Martin wanted to do was buy an American suit. They spent much of Sunday looking for a tailor who could fit him, and in the end, they found one. Elizabeth’s luggage consisted of small rugs, a few precious family photographs, and some copperware. This was all they had brought with them, most of it rolled into the rugs.

Once the family was reunited, they set to the task of earning the money necessary to survive in the New World. It wasn’t an easy life for them, but they were safely in America at last – and together.

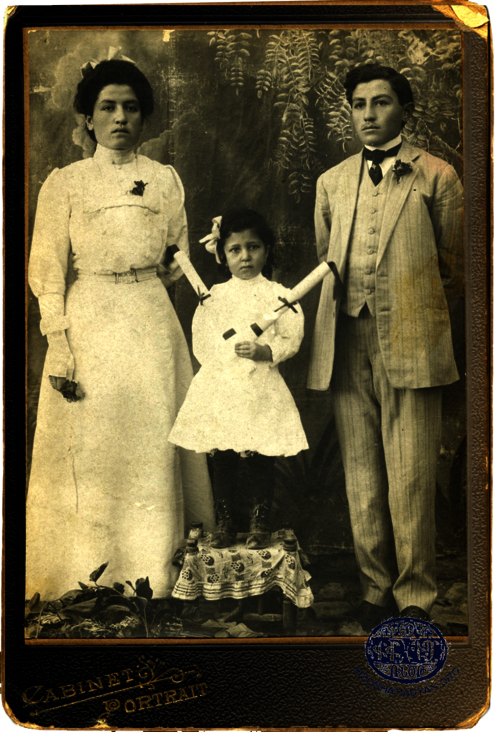

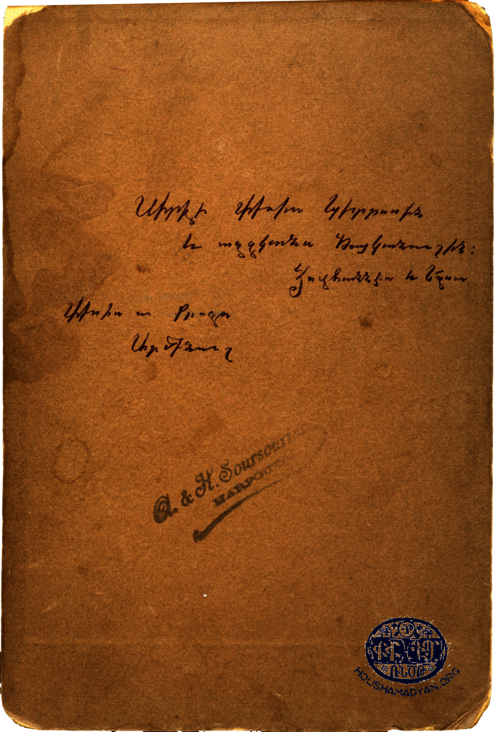

Within a few years, the Semonian brothers had left the mill and had opened a small grocery store at 369 Main Street in Charlestown, Massachusetts. When their cousins joined them in America, they too opened a store, just a few blocks up the same street. The businesses survived and grew, and the stores were a success. On July 12, 1908, Bedros/Peter Semonian married Haiganoush (Helen) Nahigian. Instead of an elaborate honeymoon, they travelled to Nantasket Beach in Hull, Massachusetts.

Helen was born in Hussenig on October 23, 1886. She arrived in America around 1904, and lived on Badger Street in Everett, Massachusetts. The Nahigians were a prominent family in Hussenig— silkworm farmers and weavers who owned giant barns. Much of their time was spent feeding the worms so they could harvest the silk. They also grew fruits on in their orchards and owned some fertile land. Throughout her life, my great-grandmother Helen was an expert at embroidery, knitting, lacemaking, and similar crafts. She knitted socks for the American soldiers during the wars and she could produce a sweater in the fraction of the time it took others. She made lace tablecloths with ease. Despite her deteriorating eyesight, she produced thousands of lace pieces. The back of every chair and the top of every table in her home was covered with one.

Helen’s father was Hovhannes (John). After John’s first wife died, he remarried. At that time, John’s children included Hampartsoum, Avedis, Haiganoush, Armenoush, Moses, Esther, and Hagop. He and his second wife had a daughter, Beatrice, born in 1907.

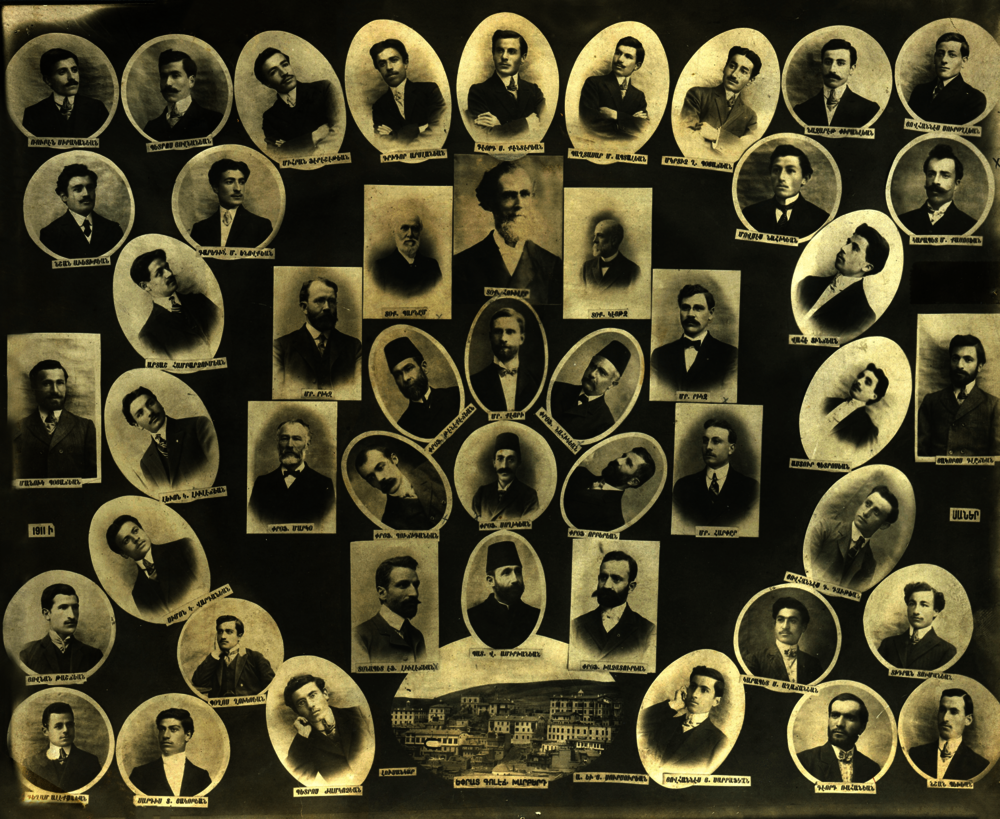

Most of the children made it to America around the turn of the century or shortly thereafter. The parents were lost in 1915. Moses was educated in the Euphrates College and Kharpert, graduating in 1911. His father’s cousin was the famous professor Khachadour Nahigian (born in Hussenig 1856 and killed in 1915), who taught at the college. When he arrived in America, Moses finished his education, played in a band, and began selling insurance and real estate.

Beatrice left her native Hussenig in 1920. By then, she had already experienced a number of atrocities and traumas, including the death of her parents and most of her extended family. She was the last of her family to arrive in America, at age 13.

Marshall’s brother Khachadour and his wife Hripsime had been caring for the Semonian clan back in Harpout while Marshall and Peter were in America.

Khachadour’s son, Nishan, came to America in 1904. By 1930, his small neighborhood grocery store had become the Fresh Pond market in Cambridge, which he ran with his brother Charles. The family remained tight-knit because back in Kharpert, they had all lived in the same house. In some cases, more than one family had lived under one roof, generally in corners of large, divided rooms.

Once Peter and Helen Semonian established a family, they began thinking about leaving the city. Their first child, Rose, was my grandmother. She was born on October 25, 1909, at the Whidden Memorial Hospital in Everett, Massachusetts. In 1913, Peter and Helen had a son, Haig; another son, Diran, in 1915; and finally, in 1918, another daughter, Elizabeth. In 1914, just after Haig was born, they decided to move to the countryside. The stress of city life had begun to show on Peter, and Haig needed goat’s milk as a baby. So the family packed up and relocated to Lexington, Massachusetts. They found a farm they could afford at 205 Woburn Street. Originally, the home was a single-family house, a large square farmhouse that had been rebuilt on the foundations of an earlier house lost to a fire. The entire Semonian family helped with the costs of refurbishing the house – Peter, Mariam, Tom, and Martin. Moreover, at one time or another, all of them, including Marshall and Elizabeth, lived in the house. There, they made home-made liquor, canned pickles, grew their own food, raised their own horses, and repaired their own shoes.

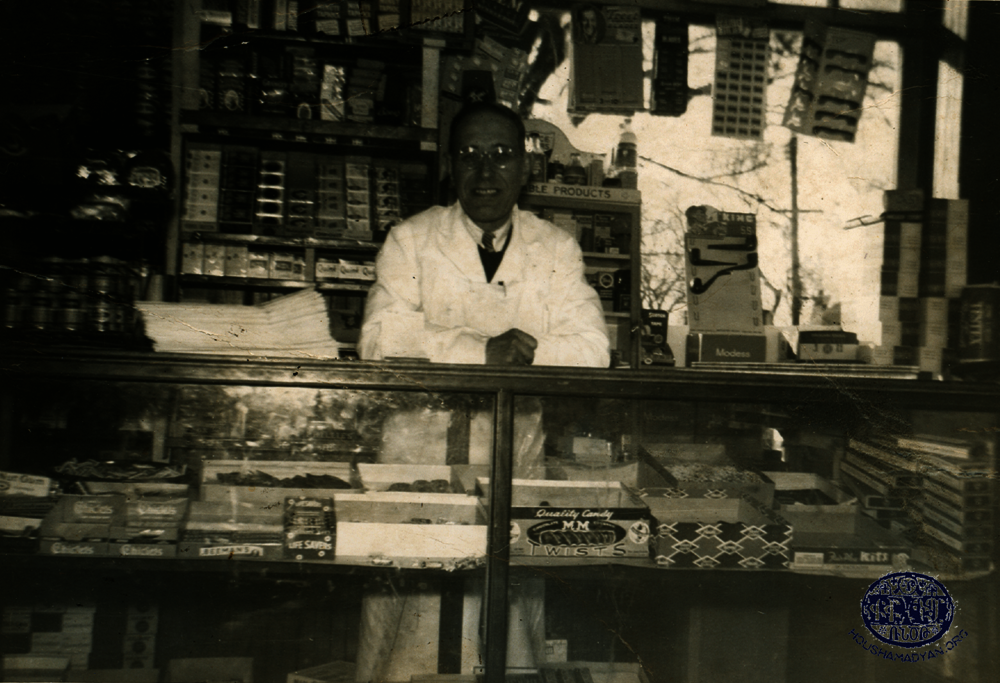

Even in his final years, Marshall was the shoe inspector any time a child in the family needed new shoes. As he aged, his health deteriorated. In particular, he suffered from intense allergic reactions during pollen season. As a result, he was frequently unhappy. He died on April Fool’s Day, 1935, much to the surprise of the rest of the family, who thought that the children relaying the news of his death were joking. They believed he was only asleep in his chair in the backyard, under the grapevine, as was his custom. His dog, Snowball, hadn’t noticed anything peculiar, either. Some years after moving to the farm, the house had been split into two separate family homes, one upstairs and one downstairs. It was the only way they could manage. Within a few years of moving to the farmhouse, Peter and Martin had launched a number of small enterprises. At one time, they sold sand and gravel dug from their property. On another occasion, they tried to raise chickens, but most died in the first winter. From time to time, their brother Tom would think up a new idea and use the farm to bring it to life. One of the most notable was the Thomas Extract Company, which produced Mayonnaise dressing, at a time when nobody had heard of it. They mixed batches of it by rigging the back end of an old truck and running a leather belt from the wheel to turn the mixer. The product didn’t sell well, so they had cases of it in the carriage house. These cases were eventually lined up against the foundation wall of the old barn and used as BB gun targets by the kids. Eventually, the family purchased a small grocery store just up the road at the corner of Cottage Street, near Lexington center. It had been Mrs. Harrison’s bakery, serving coffee and baked goods, and it was the perfect location for the Semonian Brothers grocery store. Because Peter never drove, Martin drove the only truck they had. To start it, you turned a crank on the side under the driver’s seat. Every day, Martin would drive into Boston to get provisions and then make deliveries. They sold things like Lux soap, Rinso, A&P Tea, penny candy, fruits, meats, and even ice cream.

Peter usually walked to the store, and would return home for lunch on foot, only to walk back in the afternoon. He customarily stood behind a large penny candy counter, and his store functioned as a social center for the entire community.

During the depression of the late 1920s, when few had the money for food, Peter would take IOUs as a form of payment. When they closed the store near the end of his life, the safe was found full of such handwritten notes. Peter had never collected these debts. It was important to him to help others, and he was grateful for the life he had lived. He loved paying his taxes. He loved America. He loved seeing his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren grow and prosper. Having survived the dangers of his childhood, he had a chance to live out his dream, and he relished every moment of it. He and Helen lived a full life on their farm in Lexington.

Peter outlived Helen by only a few years. He died in 1966, having lived long enough to have enjoyed the company of many of his descendants. I’m one of them, his first male great-grandchild. My mother Phyllis was the youngest daughter of Rose, who was the oldest daughter of Peter and Helen. Sometimes, it’s hard to believe the lives they led, dozens of them living under one roof at a time. They survived by staying united and facing every challenge as a family. One way or another, they overcame incredible odds. As some of my cousins say, “We rise only on the shoulders of those who came before us.” And I agree.

The Nahigian and Yeremian (Jeremiah) families, taken in Somerville, Massachusetts July 25, 1918.

Back row standing, from left: Bedros Semonian, Soren Nahigian (cousin), Eddie Jeremiah, John Jeremiah, Moses Nahigian, Avedis Nahigian.

Middle Row, from left: Rose Semonian, Haiganoosh Nahigian Semonian (wife of Bedros), Betty Jeremiah, Sarah Nahigian Jeremiah, Bobby Jeremiah, Elizabeth Nahigian on the lap of Elmas Nahigian, wife of Avedis.

Front row, from left: Haig Semonian (the little boy seated), and children in front to the right of their mother Haiganoosh, Diran Semonian, Marie Jeremiah.