Kitabjian collection – Los Angeles

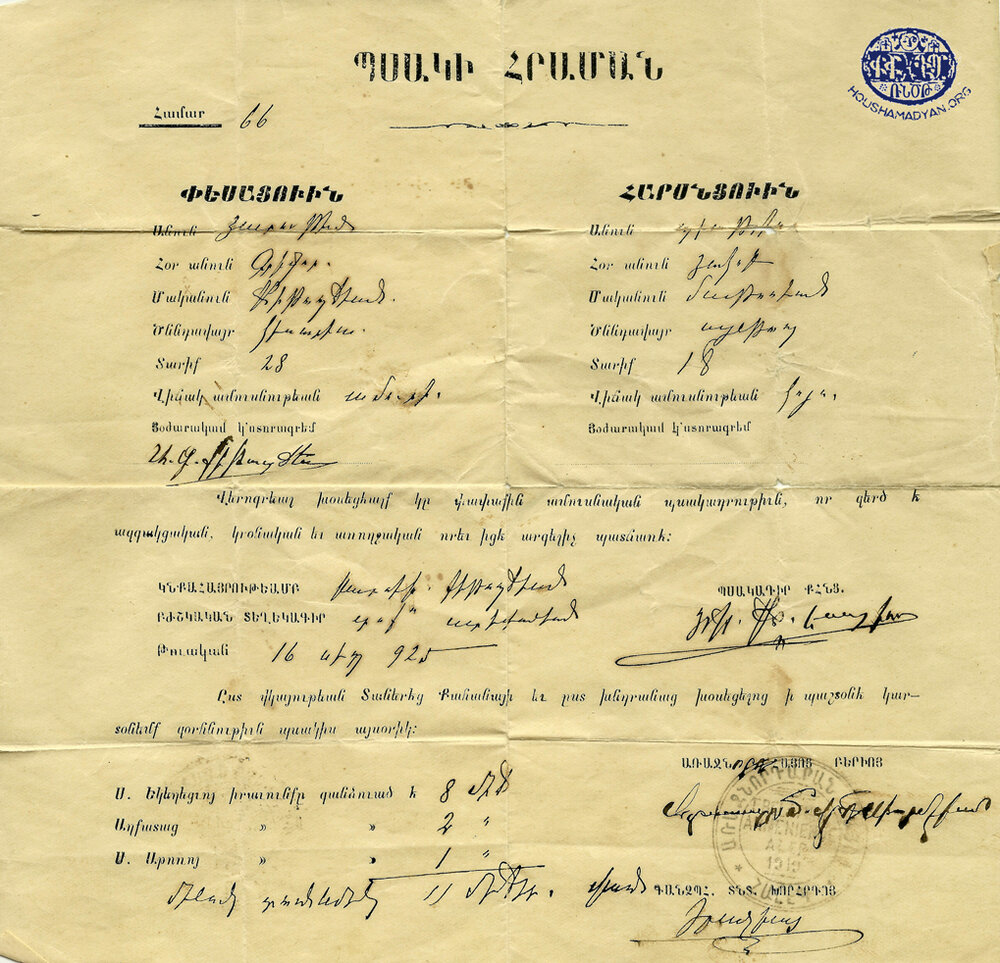

Author : Gregory Ketabgian, 13.07.20

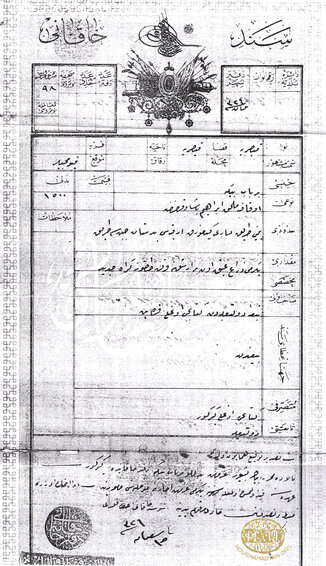

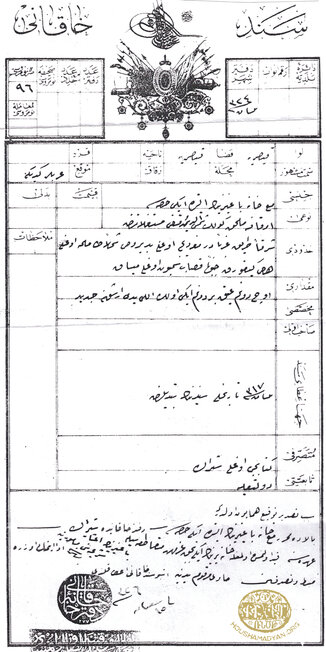

We can trace the beginning of the Kitabjians [1] in Kayseri (Gesaria) to Harutune Kitabjian who was born in Hadjin in 1810. Our forefathers, named Euredjian, had emigrated to Hadjin around the 1750s, and later to Kayseri in the 1850s. Recent genetic studies so far indicate a possible origin in New Julfa near Isfahan, Persia, where the Armenians immigrated to after being forced to leave Julfa in Nakhichevan in 1601 by Shah Abbas. Harutune was a scribe and entered the vital records of the city into the book of records in Kayseri; kitab meaning book and kitabji, the person of the book, in Turkish. Eventually his name was changed from Euredjian to Kitabjian.

Harutune Kitabjian married Srpuhy Dalghranian and had three sons and two daughters:

1) Garabed Kitabjian

2) Gulizar Kitabjian-Mouradian

3) Krikor Kitabjian

4) Hnazant Kitabjian-Odabachian

5) Setrak Kitabjian.

All three sons of our forefather Harutune Kitabjian became accomplished gold and silversmiths and were successful in their field until the Genocide of 1915.

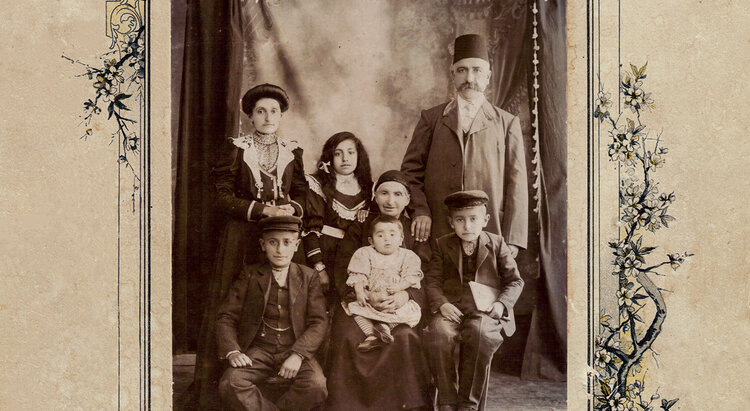

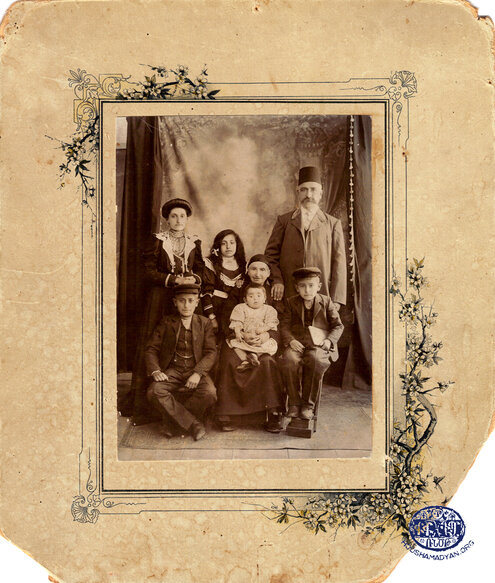

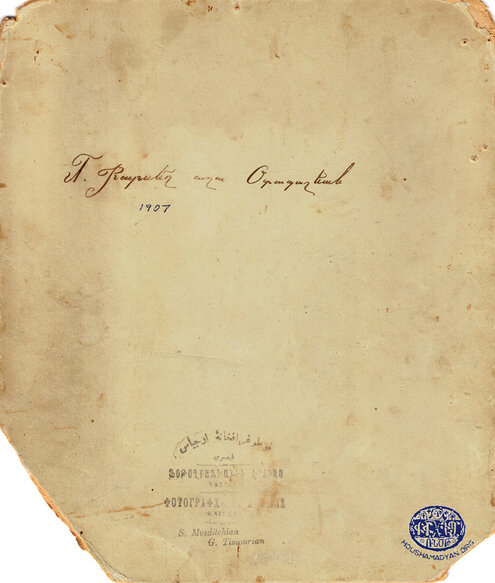

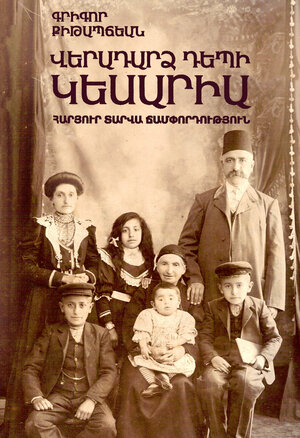

Portrait of the Krikor Kitabjian family taken in Kayseri/Gesaria in 1909. Standing from left to right: Arousiag Kitabjian (née Benlian), Hranush (Arousiag’s daughter) and Krikor Kitabjian. Seated from left to right: Artin Kitabjian (my father), my father’s grandmother Perlantin Benlian with Haig Kitabjian in her lap, and Parsegh Kitabjian. The date of 1907 written on the back with a different pen is not accurate, since Haig Kitabjian was born in 1908 and looks like one year old in the picture. The photograph survived the deportations of 1915-1918 since it was mailed earlier to a cousin, Parsegh Odabashian, who was living in Aleppo and later in Damascus. Photographers: S. Mosditchian, G. Timourian.

1) Garabed Kitabjian (1859-1915) married Antigone Jamgotchian and had four children: Harutune G. Kitabjian (1895-1936) who married Nargiz Minassian and had six children. Alice Kitabjian-Arakelian (1901-2005) who married Hagop Arakelian from Iraq and had two children. Nazar Kitabjian (1907-1980) who married Araksi Sarafian and had four children. Perouz Kitabjian-Tchokgarian (1908-1990) married Souren Tchokgarian and had two children.

2) Gulizar Kitabjian-Mouradian (1861-1915) married Misak Mouradian and had four children: Garabed Mouradian (1894-1982) who had immigrated to Boston before 1915, was the only survivor of the Genocide in his family. He married Araxy Devellian in Rhode Island and had two children. Srpuhy Mouradian, Artin Mouradian, and Arshalous Mouradian were all killed along with their mother during the Genocide.

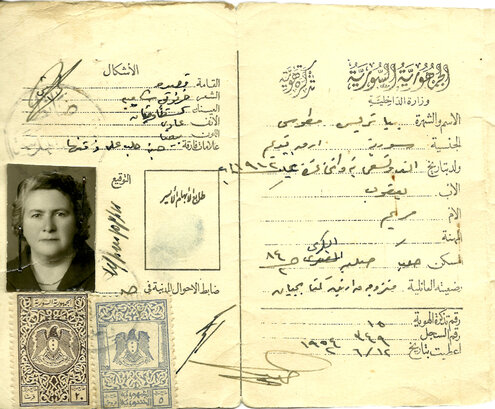

3) Krikor Kitabjian (1863-1928) married Arousiag Benlyan and had six children. Artin K. Kitabjian (1896-1987) married Beatrice Matossian from Ayntab in 1925 in Aleppo. They had two daughters and a son: Arpiné Kitabjian-Simonian (1926-2016), Shaké Kitabjian-Balekjian (1930), and Gregory Ketabgian (1936). Hranoush Kitabjian (1899-1915) died at Abu-Harara in the Syrian desert. Parsegh Kitabjian (1902-1974) married Knarig Tholakian in Beirut and had three children: Krikor P. Kitabjian (1932-2008), Arousiag Kitabjian-Palanjian (1938) and Harutune P. Kitbajian (1944). Haig Kitabjian (1908-1999) married Arpine Barsamian and had four children: Aram Kitabchyan (1946-2018), Leon Kitabchyan (1952-2016), Krikor Kitabchyan (1955) and Henry Kitabchyan (1958). Peruz Kitabjian (1910) died in childhood before 1915. Aram Kitabjian (1911-1915) died at Tetif in the Syrian desert.

4) Hnazant Kitabjian-Odabashian (1865-1954) married Parsegh Odabashian and had three children: Shammy Odabashian married Alexan Pashaian and had three children. Hagop Odabashian (1894-1970) married Peruz Bakhtiarian and had two children. Egene Odabashian was killed during the deportation of 1915.

5) Setrak Kitabjian (1867-1915) married Perlantin Paglaian and had three children: Artaki Kitabjian, Magaros Kitabjian, and Victoria Kitabjian, who died during the deportations.

During the Genocide, Garabed and Setrak were arrested and beaten and then killed on the way to Tomarza; they were stoned to death. My grandfather Krikor promised twenty gold pieces to the gendarme who had arrested him if he could spirit him away to Aleppo. This way he survived, but when he found out that his family was driven out towards Deir-Zor, he came and joined them in Bab.

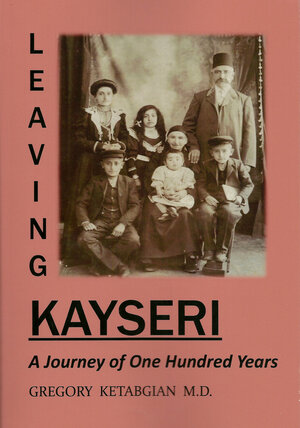

For more details on the family situation during the Genocide years, see: Gregory Ketabgian, Leaving Kayseri, A Journey of One Hundred Years, Avid Readers Publishers, 2015.

After surviving the Genocide in Deir-Zor, my father, Artin Kitabjian came to Aleppo. Here it was difficult to start a business without much capital and there were many Armenian survivors looking for work. My father Artin took a perilous journey to Kayseri in 1919 to see he if could locate and bring back a large amount of gold, silver, and antiques hidden in their home. Unfortunately, when he went into the basement to check the space between two stone walls, he found that they had been all dug up and the hidden contents were missing.

Back in Aleppo, he tried his hand as a money changer, and as an arak and antique salesman, and even opened a store in Beirut to sell their silverware products that they were producing, but due to the difficult economic times it failed and he moved back to Aleppo. Eventually he settled to run a gas station at Ramadanieh section and a store for automotive lubricants at Bustan Keleb where there were many auto mechanics fully employed. It was hard to gain the trust of wealthy Arab landowners who operated a fleet of trucks for transportation of their harvest from the fertile fields back east by the Tigris river, but developing a good reputation, selling unadulterated products, and accepting credit with a handshake were a path to success. After 35 years of daily work, he decided to retire and leave Syria and move to Southern California where his three children had immigrated.

My father married Beatrice Matossian from a family with four daughters from Ayntab after he saw her walking past his money changer’s store with her sisters. When the families met to arrange the marriage, it threw the Matossians into a dilemma since she was the youngest of their daughters and according to tradition, the older sisters would be up for marriage before the youngest. However, since they were having difficulty to provide enough food for all the members of their family, they consented.

My father’s middle brother Parsegh continued the family tradition of silversmiths and worked to produce sterling silver utensils as well as refined filigree (telkâri) candy dishes, sugar dispensers, and dessert forks and spoons. His family moved to Beirut, Lebanon, after the Syrian political atmosphere changed to a socialist state and became very unstable.

His youngest brother Haig was also working as a silversmith but due to visual disabilities he was unable to continue. He had four children, all boys. After the end of World War II, he signed up for Nerkacht, to immigrate to Soviet Armenia, however because of the delays due to Stalin’s objections after a mysterious fire on one of the ships taking immigrants through the Black Sea, they were not able to accomplish it until November 1965.

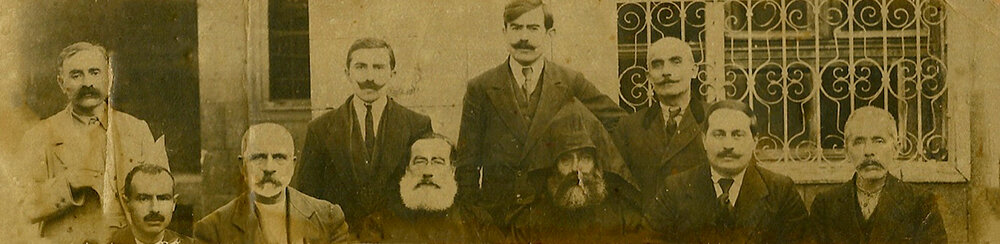

Standing, from left: Haig Kitabjian, an unknown woman, an unknown man, Parsegh Kitabjian, Artin (Harutune) K. Kitabjian, Artin (Harutune) G. Kitabjian, Narguiz Kitabjian, Alice Kitabjian, Nazar Kitabjian.

Seated, from left: Arous Kitabjian, Krikor Kitabjian, Antigone Kitabjian holding Garbis Kitabjian, Peruz Kitabjian.

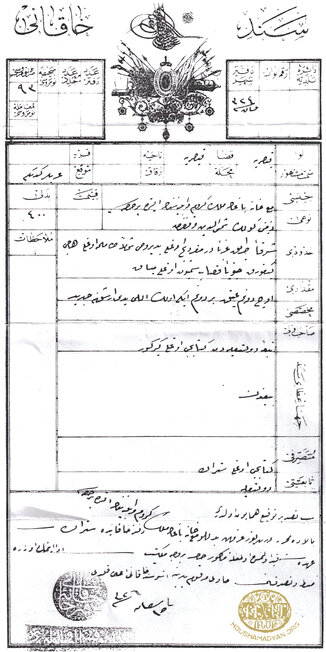

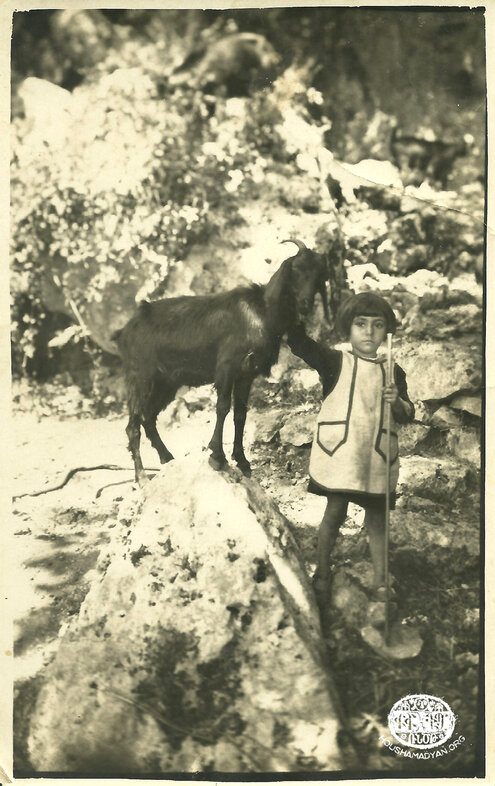

Summer vacations in Bitias (Musa Dagh)

After having left Deir-Zor and establishing themselves in Aleppo, my parents as well as some of the other members of their extended family would take short summer vacations to go to Bitias, which was one of the six main villages of Musa Dagh situated to the south-west of the city of Antioch (presently Antakya in the Hatay province of Turkey) overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. The whole region was at that time part of the French mandate of Syria and was ceded to Turkey after the signing of a Franco-Turkish agreement (1939).

These villages were mostly inhabited by Armenians and they had established an active economy for the tourist trade. It included lodging as well as active café and restaurant life. They had developed an artisanal talent of making combs, forks and spoon utensils out of a hardwood found in the region. The weather was mild typical of the Mediterranean coast with summers cooled by the breezes from the sea and the region was blessed with free-flowing streams and verdant valleys. It was quite a contrast from hot and dusty weather of Aleppo summers.

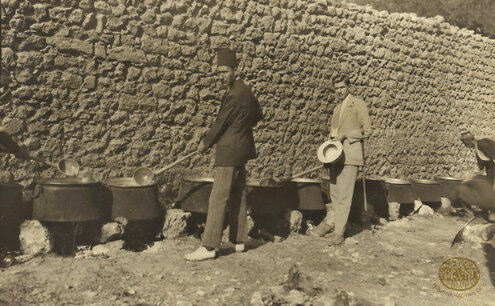

We have documentation of their visits on photographs. The years were between 1931 through 1933. There they would meet some of their friends and other family members and reminisce. By then they had started forming family units and having children which is seen with the increase of the number of children in the pictures and their growth. One of my father’s friends seen in two of the images was Levon Gerboyan who had saved my father’s and his family’s life during the deportation. He was at a junction in the desert dressed like an Arab, waving at my father who was driving an oxcart with his mother and brother in it. As they got closer, he told them to bring the cart behind a wall while the gendarmes were not looking. He told them that all the others who were going down that road east were being killed. Later, they find out that he was Armenian but had assumed an Arab’s image to save himself. He is also seen in a picture showing the famous harissa being cooked against the wall of the churchyard wall.

1. Bitias, 1931: Church courtyard with harisa, the traditional food prepared on the Feast of the Holy Mother of Christ in August. Artin Kitabjian is the third person from the left, wearing a fez and his hand resting on his daughter, five-year-old Arpine. Artin’s brother, Haig, is the fifth from the left, wearing a cap and tasting the harisa. The sixth person from the left wearing a fez is Levon Gerboyan; the seventh person from the left wearing a fez is Parsegh Kitabjian.

2. Bitias, 1931. Harisa cooking against the wall of the churchyard.

Harutune Cholakian (later Father Karekin)

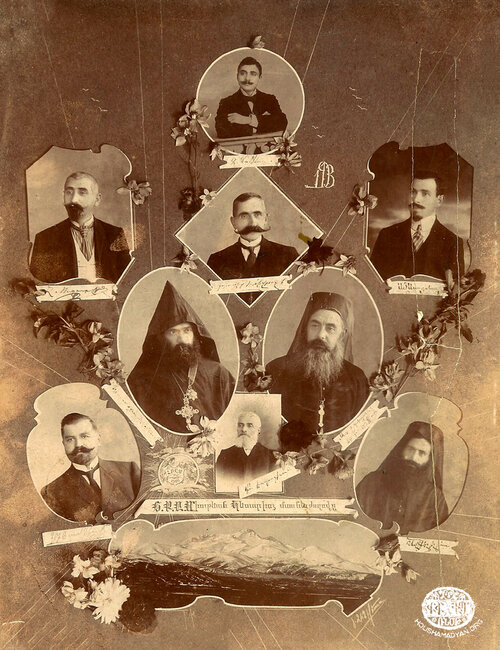

The father of Aunt Knarig, wife of my uncle Parsegh Kitabjian, who also was from Gesaria (Kayseri), Harutune Cholakian (1842-1931), was an educated man. He was a teacher of the Gumshian (1900-1901) and Miatsyal Ousoumnaran (1903-1904) schools in Kayseri/Gesaria, as well as a deacon at Sourp Krikor Lusavorich Church.

He and his family were not deported during the Genocide in 1915, because Cholakian knew French and the Ottoman army was using him as a much-needed translator for German officers, since they knew French. After the end of the war they remained in Kayseri until 1923, when they moved to Syria. Cholakian and his family were settled in Jarablous, in the North of Syria, where he opened an elementary school for Armenian children; he was assisted by his daughter Knarig, as one of the teachers. He was ordained into priesthood (kahana) in 1925 by Catholicos Sahag in Beirut. His name was changed to Karekin at that time. Then the family moved to Aleppo and he became one of the main priests at Karasoun Manoug Armenian Apostolic Church of Aleppo.

Dr. Mihran Krikor Kassabian

Dr. Mihran Krikor Kassabian (1870-1910) who was born in Kayseri and became one of the original investigators and researchers of radiology was distantly related to our family through marriage. My cousin Mary Dekmejian-Kassabian is married to Dr. John Kassabian, whose father’s uncle was Dr. Mihran K. Kassabian.

Dr. Mihran Kassabian received his early education at the local American Missionary Institute in Talas, then journeyed to London to further his education in photography, theology and medicine to prepare himself for work as a missionary. He emigrated to Philadelphia to study medicine at Medico-Chirurgical College right when Roentgen rays were discovered in 1885 and were starting to be used in clinical medicine. He volunteered during the Spanish-American War, where he used x ray fluoroscopy extensively for diagnostic work. He got his degree in medicine and his citizenship at his discharge from the military in 1898. However, he had already sustained early radiation exposure of his hands as x-ray of the hand was used to calibrate the cathode rays. Further exposure of his hands and ongoing injury to the tissues plagued him throughout the remainder of his short life and eventually succumbed to metastatic skin cancer following three operations to limit the spread of the cancer. He died in 1910 and is buried at Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. He had written one of the seminal textbooks on radiology, the second edition of which was published the year he died. In 2019 Scholar Select republished the book to keep it available for future scholars. [2]

- [1] The spelling of the last names have been altered depending where some of the members have lived; Ketabgian upon immigration to the US; Soviet Armenia after Nerkakht: Kitabchyan and to Egypt: Kracerian.

- [2] Mihran K. Kassabian, Rontgen Rays and Electrotherapeutics, Wentworth Press, 2019.

Photos and objects