Kazanjian collection - Los Angeles

17/02/22 (Last modified 17/02/22)

The Kazanjian Family – A Brief History

Author: Deirdre Casparian

Pilibos, the youngest son of Hovannes/Ohannes Kazanjian and Yeghsapet Kazanjian (née Aharonian), was born in 1870 in Keserig/Kesrig (present-day Kızılay), in the Kharpert/Harput Valley. When he was about a year old, his father moved him and some of the family to live in nearby Hussenig (present-day Ulukent), including his mother, Yegsha; and his three brothers, Hagop (ten years old), Bedros (nine years old), and Hovannes/John (four years old). His sister, Maritsa (later Terzian), was born there seven years later. The children of Mariam Hazarkhan, Hovannes’ first wife, remained in Keserig. The names of these half-siblings are known, but their dates of birth are not. They were Donabed, Boghos, Garabed, Simon, Aslan, Khaplan, and Rrayan.

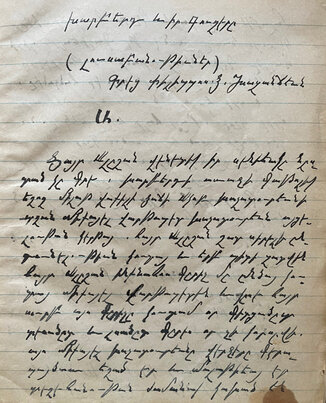

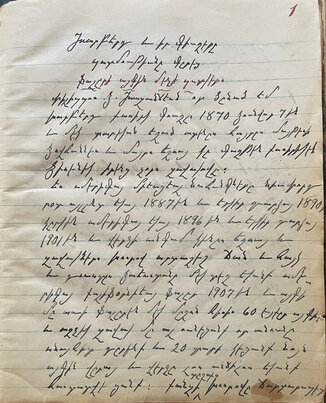

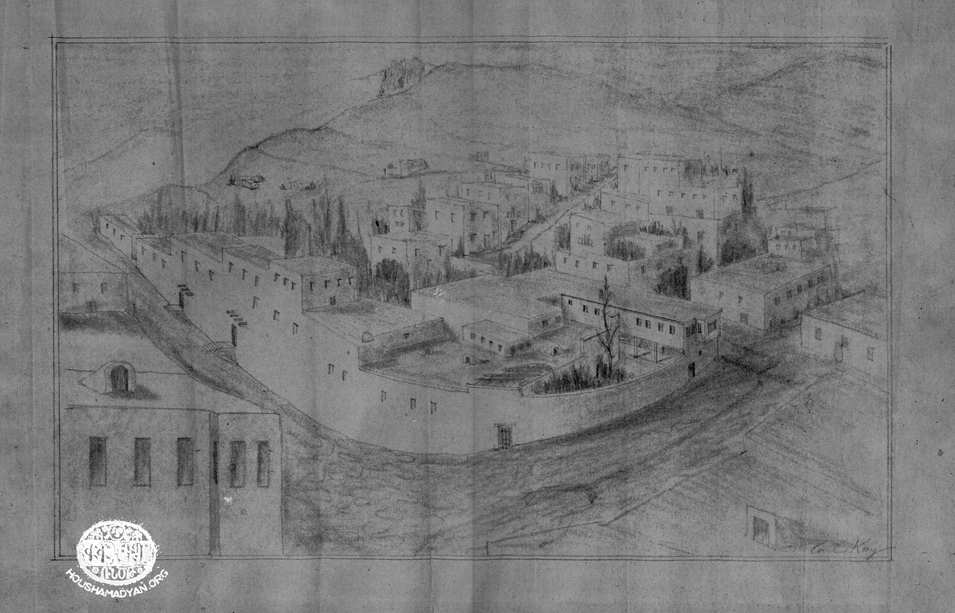

Pilibos is the author of a lengthy manuscript. The manuscript’s Armenian title is Kharpert yev ir Kyughere [Kharpert and Its Villages]. It is mostly based on Pilibos’ own observations and what he had heard from his compatriots. The manuscript also includes long passages about Pilibos’ own life, which adds to the autobiographical nature of the work. Much of the information used on this page is taken from Pilibos’ memoirs.

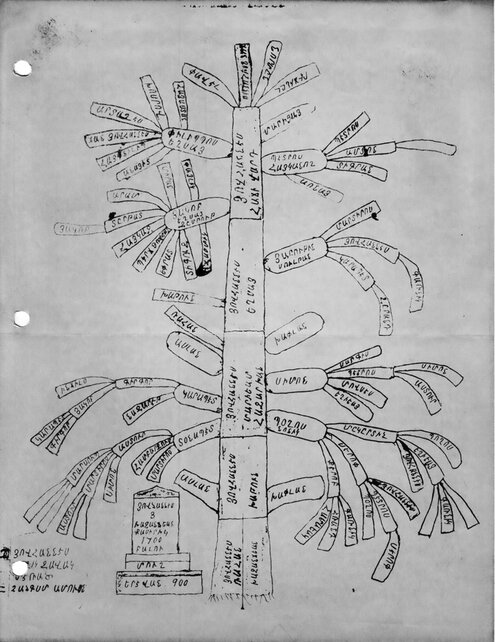

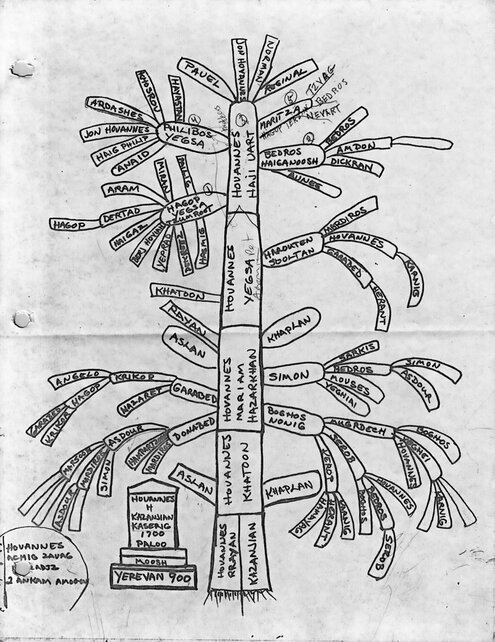

Pilibos died in 1936, before he could publish his manuscript. His handwritten notebooks and captioned photographs are now in the possession of his great-grandchildren. In his work, he mentioned a Bible that was kept at the house of Khazanji Mghdes Ovannes, in the town of Palu, and which contained important family information. Sadly, this Bible has not been discovered. But we have the family tree drawn by Pilibos based on the information it contained.

The Kazandjian/Kazanjian family tree, prepared by Pilibos Kazanjian around 1929-1930, and translated by Beatrice Casparian, his granddaughter, in 1977.

Click on the PDF version for more details.

Pilibos tells us that one of his grandfathers was a butcher, and the other a community leader. It is probable that many of the members of the family in earlier generations were coppersmiths. This would explain the family’s surname, which, according to custom, describes the family’s traditional occupation in Turkish.

We do not know why Hovannes Kazanjian moved his family to Hussenig, but the relocation meant that the children could walk up the hill to the expanding Euphrates College, the American missionary school located in the city of Kharpert/Harput. In 1880, Bedros Kazanjian was enrolled in the school’s first graduating class. We can assume that the family’s move to Hussenig was a pragmatic decision that allowed Hovannes to more easily manage the large farms he owned in the villages of Morenig (present-day Çatalçeşme) and Vartatil (present-day Yazıkonak). Alternatively, the move may have been motivated by Hovannes’ desire to be closer to the commercial endeavors that he had embarked upon. He had established a partnership with hadji Hovhannes, hadji Haroutioun, and hadji Hagop. These men were members of the family, but his exact relationship to them is unknown.

It is also unclear when the family first became involved in commercial trading. Opportunities were plentiful. Pilibos mentions that they were international merchants, exporting carpets, embroidery, and antique guns to the United States; opium to Great Britain; and raw silk, fox fur, and wolf hides to France. They may have also exported opium to the United States, where it was legal, and many Boston fortunes were made by illegally selling it on to China. Pilibos mentions that they imported soap and oil from Aleppo, and European goods from Constantinople.

This merchandise would have been transported in traditional camel and mule caravans. Family stories memorialized these caravans, as did the rugs woven by Pilibos.

While Bedros attended Euphrates College, his brother Hagop was already married and engaged in commerce. He was probably based in Tiflis, in Tsarist Russia. It is likely that Bedros was involved in this venture, as well as the management of the extensive family farms.

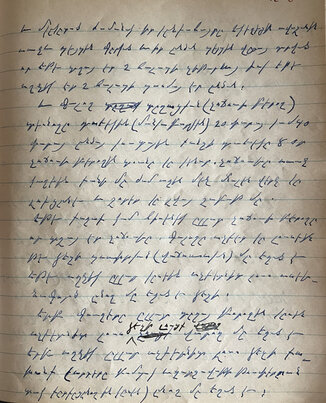

The Parigian family were close friends of the Kazanjians from the village of Keserig. As recorded by Elizabeth Kuzirian, who married Harry Bagdasar, the younger of Apraham Parigian’s two sons, the Parigians lived in the small mountainous neighborhood of Sinamoud, in the city of Kharpert. The three brothers, Apraham, Dada, and Manoug, owned the only foundry in town, where they made and repaired all kinds of machinery, tools, and sewing machines. They also made keys. Moreover, they owned a flour mill that was run by both manpower and waterpower. Manoug was the salesman. Around 1880, he returned to Kharpert from America, where he had gone to study machinery (in Providence, Rhode Island). He brought back a lathe, and possibly the information that the rich Americans of Newport were a receptive market for oriental rugs. At that time, many Armenians were making their fortunes by working in factories in Massachusetts.

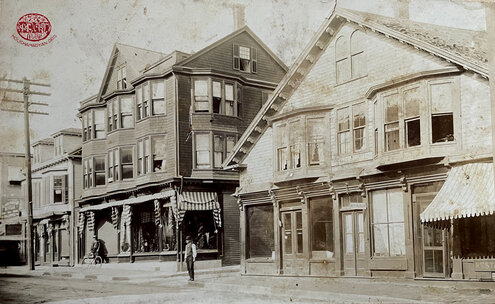

After Bedros graduated from Euphrates College in 1880, he took the first of many trips to the United States. At first, he worked in the shop of another Armenian carpet seller in Boston. Before the year was over, he became the first Armenian to settle in Newport, Rhode Island, setting up an importing business from a rented room on Bellevue Avenue. His father sent him rugs and other cargo from Hussenig, which he sold in Newport. As the business grew, his brother John joined him, as did Pilibos, Marsoub (grandson of Donabed), and Mihran (son of Hagop). Eventually, the Kazanjian Store occupied most of the street.

Pilibos was 17 years old when he arrived in the United States in 1887, and he stayed only for three years. According to family lore, he flirted with the customers! Perhaps he was missing his sweetheart, Yeghsa Parigian (1874-1962), the oldest daughter of Apraham Parigian. After Pilibos’ return in 1890, Apraham informed him that before he could marry Yeghsa, he needed to prove he could support a wife, and that if being a merchant was not to his liking, he needed to learn a trade. Perhaps Pilibos dabbled in the family butchery business, as he was the first to bring a meat grinding machine to the Kharpert region. In his memoirs, he wrote that the machine had three cylinders and was powered by pedals, like a children’s tricycle.

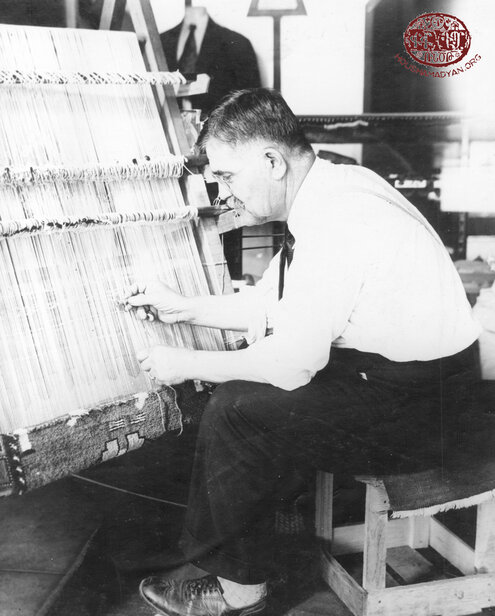

Eventually, Pilibos learned to be a tailor. He continued to help manage the family farms, and also helped his brothers procure local rugs to sell in America. It may have been his work as a tailor that helped pique his interest in the weaving of rugs. We know of three rugs that he wove in later years. The first was to celebrate his American citizenship, the second to commemorate memories of Hussenig, and the third to exhibit at the 1932 Olympic Games.

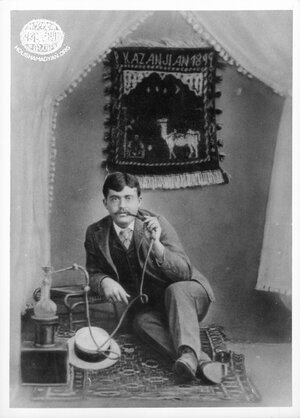

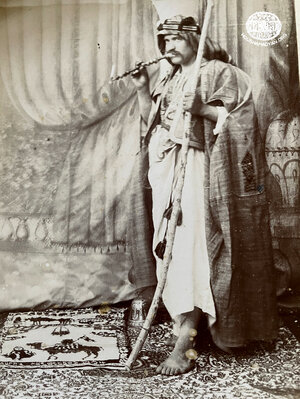

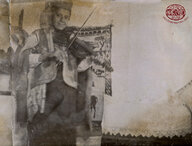

Pilibos Kazanjian, casually smoking a hookah. Hanging from the wall behind him is a rug that he wove himself. This was the first rug woven by Pilibos, and it celebrated his U.S. citizenship, which he obtained on June 6, 1899. The rug bears his name and his citizenship date, as well as a camel. The photograph was probably taken in Constantinople, in 1900, and sent as a keepsake to his father, Hovhannes Kazanjian.

Pilibos and Yeghsa had two sons, Khosrov and Ardashes. Bedros married Haiganoush Aghassarian in Constantinople and took her to Newport just before the anti-Armenian Hamidian massacres of 1895. John was not so lucky. When he returned to marry after eleven years away, he and his bride, Vart Harpootlian, were unable to leave until after the massacres of 1895. Pilibos mentions that the Kazanjian family escaped the violence by taking refuge in the city of Mezire/Mamuret-ul-Aziz (present-day Elazığ).

Pilibos rejoined his brothers in America in 1896. He worked in Newport and stayed long enough to become a U.S. citizen. He brought with him portraits of his wife as a bride, as well as photographs of her with their two little boys. During this time, he purchased a Kodak camera, with which he likely sent photographs back to Hussenig. After an absence of five years, and now a U.S. citizen, Pilibos returned to Hussenig in 1901 with his Kodak camera. He would have continued working with his brothers in the carpet/rug trade and managing the family farms. We presume that most of the pictures depicting street scenes, family life, and friends were taken by Pilibos himself. In 1907, this time accompanied by his wife, Yeghsa; his five children (Khosrov, Ardashes, Hayastan, John, and baby Haig); and his wife’s half-sister, Azniv/Takoohie, Pilibos set out once again for America. After this third journey, he did not return to his homeland, and settled down permanently in the United States with his family.

Pilibos took his family to live in Fowler, California, where he was engaged in fruit farming for the next twenty years. His daughter, Anahid/Diana, was born there. In 1928, he moved to Los Angeles, nearer to his sons. Carl/Khosrov was an architect, and Arthur/Ardashes was a dentist. Another one of his sons, John, having completed college, decided to become a professional wrestler. The family tree was drawn to help John identify himself to his Armenian cousins. Haig studied pharmacy, Hayastan raised two daughters, and Anahid/Diana apprenticed with a dress designer.

Pilibos’ father died around 1904. The fate of his mother remains unknown.

Excerpts from Pilibos Kazandjian’s Unpublished Work "Kharpert and Its Villages"

Translator: Simon Beugekian

Across the 832 pages of his unpublished work, Pilibos Kazanjian recorded the history of the city of Kharpert and many nearby towns and villages (Hussenig, Morenig, Kasirig, Soursouri, Pazmashen, Khoulakugh, Vartatil, Parchandj, Kaylou, Khouylou (Tlgadin), Ertmuneg, Ichme/Ichma, and Garmir). The author wrote in simple prose, using conversational language, effectively the Kharpert Armenian dialect. Many of his descriptions of events and persons are first-person, witness accounts. In other cases, he conveyed information that he had learned from his elders. In this sense, Pilibos’ work is uniquely valuable, as it contains entirely new information that is not found in other primary sources that chronicle the history of the Harput/Kharpert area.

Here, we present select excerpts from this extensive work. We hope that in the near future, we will be able to present the entire manuscript to the public. The original work was only edited to correct orthographical errors and to add appropriate punctuation. We have mostly preserved the manuscript’s original style. Editorial changes are marked in brackets.

The Parigian Brothers’ Iron Foundry in the Sinamoud Neighborhood of Kharpert

Dikran Terzian and Kevork Tashdjian learned how to forge iron in America. When they came back to Kharpert, they built a large foundry in the yard of their home, in the Upper Neighborhood, across the street from Kyurkdjian Pavlukadjonts’ [1] home. They intended to use this foundry to make the metal parts of wheat winnowing machines. When they first lit the foundry, the local Armenians rushed to the authorities and reported a large fire in their mayla [neighborhood]. Upon arrival, the authorities forbade the brothers from operating the foundry. This was 46 years ago. Then, [Terzian and Tashdjian] went to Sinamoud [neighborhood], where they worked at the factory owned by the brothers Apraham and Manoug Parigian. These two brothers were blacksmiths and locksmiths, and also owned two flour mills, where they had built forges to smelt and forge iron. As for the coal, they brought it from Samson on camelback, which was very costly. They went to the Zarfanig Garden, near Kharpert, two hours north of Mezire, where there was a source of myrrh. But the government would not allow them to dig there. Terzian and Tashdjian returned to America. The Parigian brothers were from Hussenig. Every day, they would come to their factory in Sinamoud. From America, they had brought a lathe and a drill. The wheels were powered by water. They began producing cotton gins, which bore the inscription “Parigian Brothers, Kharpert” in Armenian, Turkish, and French. (Pages 58-60)

… Dikran Tashdjian from Kharpert, who is known by the surname Taylor in America, and his brother-in-law, hadji Kevork Tashdjian, as I have already said, brought a torno engine and a lathe from America in 1888. They also brought the parts of wheat winnowing machines, both the metal machinery and the shell. Apraham and Manoug Parigian, from Hussenig, began making cases and selling the winnowing machines for 10 Ottoman pounds. Dikran Terzian and Apraham Parigian were hadji Kevork Tashdjian’s sons-in-law. Throughout the area, the villagers had hitherto been forced to pile their wheat up in the open, check the direction of the wind, and then use a pitchfork to toss the wheat into the air. It was difficult work, and the threshing floor was often exposed to the rain in the winter. This device was of huge benefit to the villagers. At first, only 100 sets were imported, but the men soon imported many more. The three Parigian brothers and the son, Orsep Parigian, would cast the metal themselves. In later years, they went into partnership with [illegible], Ettarian from Hussenig, and Khalunian from Kasirig. They would import 100 sets from America each year. The Kyurkdjian brothers in Hussenig would import another 100 sets per year, also from America.

The Parigian brothers of Hussenig were the first to use these winnowing machines. They made them available at the threshing floors, where the machines would separate the wheat grain from the chaff. People would come from all the nearby villages and wonder at the machine. The grain would flow in one direction and the chaff in the other. Previously, they had been forced to use the wind to winnow the grain, and often the wheat would be left out in the rain.

The locals began purchasing these machines. First, only a few farmers in each village, but the demand soon grew. People from Palou, Malatya, Arapgir, Dikranagerd [Diyarbekir], Moush, Bitlis, Erzurum, and Sivas all came to Kharpert to buy their own. In later years, a thousand of these machines were being sold each year. They were a great help to the farmers. They required little effort to operate and saved a great deal of time. The machines could also sift a household’s grain. Previously, the women had been forced to sift it manually. (Pages 108-109)

… Apraham Parigian built the first mill that could grind bulgur [groats]. It was powered by a horse. Previously, groats were cracked by hand, using a grindstone. (Page 161)

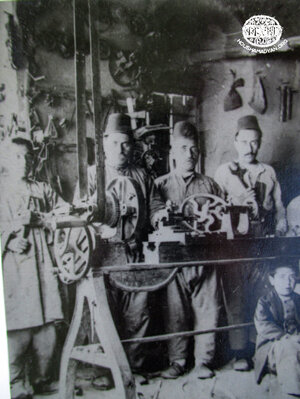

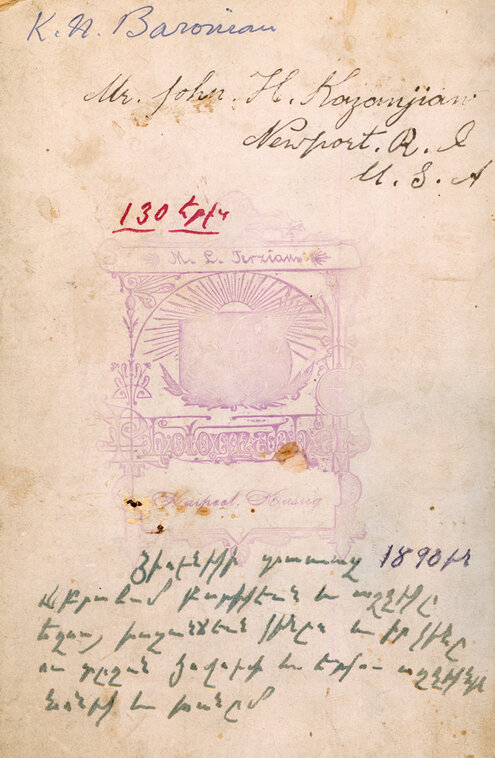

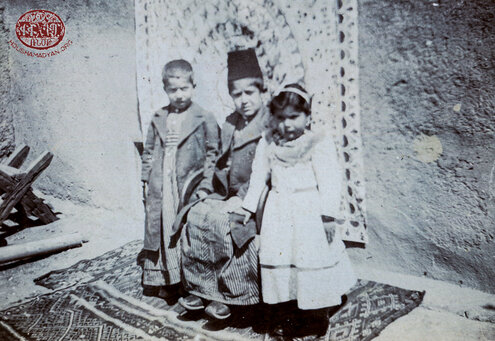

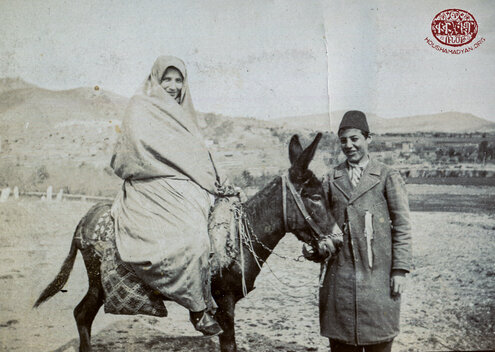

Hussenig, 1890. Seated, left to right: Apraham Parigian and his second wife, Maritza Parigian (nee Kavdjian). Standing in the back row, left to right: Yeghsa Parigian (later Kazanjian) and Hovsep Parigian, the children of Apraham and his first wife, Nonie Tashjian. The young girls are two of Apraham and Maritza’s four children. Nonig Parigian is seated on the floor. She died with her children in 1915, drowning them to avoid their being massacred. Standing on the right is Khanum (also known as Takouhie/Queenie), who later moved to Rhode Island to marry Leo Tahakjian. Two children are missing from this family photograph. One is Satenig, who later escaped to France, and where her husband Nishan Sevajian died. Her second husband, Levon Sabbagh, brought her to the United States. The second child missing from the photograph is Harry Bagdasar, who was sent by his uncles and brother to the United States in 1911. There, he married Elizabeth Kurzirian. (Photographer: M. L. Terzian, Karpoot [Kharpert/Harput], Kasrig [Keserig]).

A Song Sung by Kharpert Turks about the 1895 Massacres of Armenians

During the 1895 massacres, the Turks came up with a song about Armenians, in Turkish:

Mazira’nın yolu budur

Çifte guğüm dolu sudur

Baglig [özgürlük] istiyenin hali budur

Yandım dolana dolana

Ey Ermeni kızı gel im

[Translation]

This is the road to Mezire

A pair of gougoums [clay canteens] are brimming with water,

This is the fate of those who seek liberty,

I rolled around burning, rolled around burning,

You, Armenian girl, come embrace the faith [convert to Islam]. (Pages 101-102)

Armenians from Kharpert Found a New Village Near Diyarbekir

A group of people from Kharpert formed a partnership and purchased land on the eastern side of Diyarbekir. It was a large field, on the further side of the river. The field had a plentiful source of water thanks to the stream that crossed it, called Anbar Chay [Anbar Brook/Stream]. There, this partnership founded a new village, which they also called Anbar Chay.

Those who purchased the field were: Reverend Mardiros Shmavonian, Sarkis and Mikayel Shukhloyan, Hagop Banayan, Garabed Banayan, Kalgonts Manoug, Kevork Dindjian, Te[k?]madji Garabed, Dikran Terzian (who is now known as Dick Taylor in America), and some others.

They purchased the field in 1881 and created a system of shares. Each share was valued at 10 Ottoman pounds. Each participant could buy as many shares as he wished, and was allowed to settle down in the village, build a house, and receive a plot of land commensurate with the number of shares he had purchased. The first to build a house there were the Shukhloyan brothers, Kalgonts Manoug, and some others. They soon set to work, cultivating the land and growing vines, mulberry and poplar trees, and rice.

The others wanted to wait a year or two – they would move if the initial experiment went well, and if not, they would stay put. Many farm workers from the village of Buzmushen [Pazmashen] of Kharpert went to Anbar Chay, where they were provided with accommodation. But they all returned to Buzmushen within a few years, as the climate of Anbar Chay was not hospitable. It was a muddy, waterlogged place, where malaria ran rife. Only two households of Buzmushen Armenians stayed in the new village until the end – those of Hampo and Apraham Kayayan.

Kalgonts Manoug died in Anbar Chay of malaria. The village was left to the Shukhloyan brothers and Hampo and Apraham Kayayan, who invited Kurdish farm workers to cultivate the land.

That first year, each shareholder received a sack of chaltoug (rice still in its husk). This was the last payment they would ever see. Many put their trust in Reverend Mardiros Shmavonian, as he was the son-in-law of the English consul in Dikranagerd, Reverend Thomas. They believed that Reverend Shmavonian could protect the village from the Kurds. Eventually, all the shareholders abandoned the village. Only the Shukhloyan brothers remained. They stayed until the massacres of 1895, during which the entire village was burned to the ground, and all remaining Armenian residents were killed. In the few years prior to the massacres, the residents had planted many orchards and fruit trees. Anbar Chay had become a haven of mulberry trees that could be used in sericulture. The village was also home to a large grove of poplar trees. The locals were growing wheat, rice, cotton, beans, chickpeas, lentils, etc.

At a distance of five to six hours from Anbar Chay were the Kurdish villages of Lidje and Hayni. The Kurds living in those villages had to make their way through Anbar Chay to travel to Dikranagerd [Diyarbekir]. They took advantage of this fact and robbed the village blind. During the 1895 massacres, the English consul, Reverend Thomas, suffered a heart attack and died. (Pages 110-111)

Armenians Bring American Novelties to Kharpert

The first to bring bicycles to Kharpert from America were Boghos Vartabedian and Krikor Boyadjian. These bicycles had a large front wheel and a small rear wheel. The two men would sometimes ride them when they went to visit the vali[governor] or when an official came to visit the town. The Turks called these bicycles djansuz al (horses without souls). (Page 157)

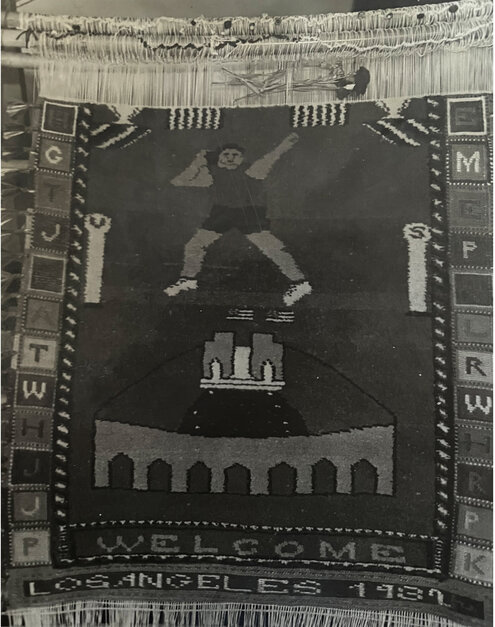

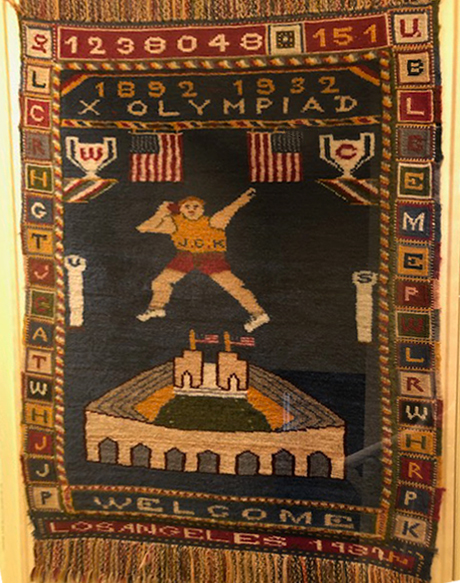

The Rugs Woven by Pilibos Kazandjian

Pilibos H. Kazanjian, while still in Hussenig, wove a Persian rug that features the entire Armenian alphabet. He wove another rug in 1907, which features his family tree, including his children’s names, and which bears the inscription “Kharpert Hussenig 1907.”

He wove a third rug later in his life, after moving to the city of Los Angeles. A photograph of him and this third rug appeared in the Los Angeles Examiner, Los Angeles Herald, and Fresno’s Mshag newspaper. At the top of the rug is the population of Los Angeles and the name of the city, which was founded 151 years earlier. The dates 1892-1932 refer to the Olympic games, whose modern iterations began in 1892. In 1932, the tenth modern Olympics were hosted by Los Angeles. The Armenian tricolor appears on both sides of the rug. In the center are two American flags, waving, hanging from the cups. One cup bears the letter W, short for “World,” and the other C, short for “Champion.” The rug also features my son, who’s putting a shot and whose jersey bears his initials, JCK (John Casey Khazandjian). The two strips on each side of him bear the letters U and S, short for the United States. At the bottom is the Los Angeles Coliseum, where the athletes will compete in the Olympic Games. Below it is the inscription, in English, “Welcome to Los Angeles,” followed by the date, 1932, and Kh., which stands for Khazandjian.

On the borders of the rug is a set of initials. Only General Andranik’s are in Armenian. The rest are in English.

“ZA,” or “Zoravar Antranig” [General Antranig], who fought for the Armenian people for 40 years. “LB,” or Luther Burbank, the breeder of plants and fruits. “CL,” or Charles Lindbergh, who crossed the ocean alone in an aircraft. “RB,” or Robert Byrd, who discovered Antarctica from the air. “HH” [sic], or Hugo Eckener, who circumnavigated the Earth in a zeppelin. “GM,” or Guglielmo Marconi, who invented the radio. “TA,” or Thomas Edison, who invented the lightbulb and many other things. “JP,” or James Pershing, who commanded the American forces in World War I. “JW” [sic], or George Washington, the first president of the United States. “AL,” or Abraham Lincoln, who fought for the liberation of slaves. “TR,” Teddy Roosevelt, a great president of the United States. “WW,” Woodrow Wilson, another great American president who also drew the geographic boundaries of Armenia. “HH,” or Herbert Hoover, the incumbent president of the United States. “JR,” or James Rolph, California’s representative in Washington [sic]. “JP,” or John Porter, the governor [sic] of Los Angeles. And finally, “PK,” or Pilibos Khazandjian, who wove the carpet. (Pages 157-160)

… I have woven four rugs. One in the city of Newport, Rhode Island in 1898, and the other two … in 1904 and 1907, in Hussenig. The rug I wove in 1904 bears the name of my son, Khosrov Khazandjian, and the Armenian letters P. Kh. (Pilibos Khazandjian). It also features an Arab on camelback and a woman standing beside two water jugs and holding the reins of an ox chariot. This rug also features the entire Armenian alphabet.

The inscription on the third rug reads “Kharpert Hussenig 1907.” It features two women, one wearing a zboun [frock], and the other wearing a shalvar [baggy trousers]; and a ram. The women are pictured churning yogurt. The rug also features a camel with its calf and the camel keeper, as well as our family tree. Upon the tree is a boy playing a shepherd’s flute. Each branch bears the name of one of my children, in order of age: Kh. Kh. (Khosrov Khazandjian), A. Kh. (Ardashes Khazandjian), Y. Kh. (Yeghsapet Khazandjian), Dj. V. Kh. (John Vanderbilt Khazandjian), and P. Kh. (Philip Haig Khazandjian).

On one side of the tree is a wellspring, with an arch above it, and a stork perched on the arch. The water flows towards the tree. Beside the tree are a cow and a calf, and the Armenian letters Y. P. Kh., which are my wife’s initials (Yeghsa P. Khazandjian). I also wove a rug in Los Angeles, California, about which I’ve already written. (Pages 276-278)

Description of the Massacres of Armenians in 1895 in the Kharpert Area – Witness Testimony

I will now write about the massacres and looting that occurred in Hussenig on October 30, 1895. About 15 to 20 days before these events, we heard that Armenians were being robbed and shot, but the culprits were supposedly Kurdish brigands. The government crier announced that people were barred from leaving their homes after 12:00 o’clock, which was 6:00 o’clock in western timekeeping. In this way, the authorities aimed to prevent people from communicating with each other. A week before the attack on our village, Turkish soldiers, dressed in the local garb, and pretending to be Kurds, were killing and robbing the Armenians of distant villages. In the village of Kasirig, the troops converged on the home of Yaghdji Oghli Krikor Effendi, but Krikor Effendi, with a group of armed youths, fought back and repelled the attack. However, the soldiers then returned in their uniforms, and Krikor Effendi was forced to hand himself in, alongside his 24 friends. They were all taken to Mezire and imprisoned there.

Manso Koko’s son and a few [illegible] came to Hussenig from Kasirig, to Minas Mazmanian Agha’s home, as his wife was a native of Kasirig. Many of us Armenians went there to hear the news. They said that the massacres were not being committed by Kurds, but by soldiers.

Until then, the people of Hussenig had been preparing to face the Kurds. They had been filling copper tubs and jugs with water and storing them, so that they wouldn’t be forced to leave their homes for water. The women had been burying their valuables or hiding them with Turkish friends. But all hope was lost when the Armenians escaping the village of Hatselou started spreading news of how the attackers had massacred the locals and had burned down the village, and how they had abducted the women and girls.

Most of the Armenians of Hussenig fled to Mezire, where they were safer. Some found refuge with the begs of Saray or with other Turks. On the morning of Monday, October 30, 1895, the village was surrounded by troops dressed as Kurds. They had come with their military bugle. Moustafa Pasha was the one issuing the orders with the bugle – forward, back, ready, and fire. He was sitting in his chariot, and the charioteer was Brother Yeghazar from Saray. He told me that the city [illegible] and that the order to shoot was given by Moustafa Pasha. A small cannon had been towed there by seven mules, and was later transported from Mezire to the city of Kharpert. I saw this with my own eyes, as I had escaped to Mezire. We were at the home of Kerop Khazandjian and watched everything from the windows. They even brought the cannon to Hussenig and positioned it in the Turkish cemetery, ready to use it if necessary. They didn’t use it in Hussenig, but in the city of Kharpert, they destroyed the missionaries’ buildings and the homes of Armenians with the cannon, burning them to the ground.

In a single day, the mob attacked and looted Hussenig, Sinamoud, the Assyrian neighborhood, part of the Saint Garabed neighborhood, and the Saint Hagop neighborhood [in the city of Kharpert]. The Beg Oghli of the city did not allow them to attack the Saint Sdepanos neighborhood [in the city of Kharpert]. Thousands of Turks and Kurds had come from the nearby villages to participate. In the morning and through noon, they attacked and robbed whomever they fell upon, and set houses on fire. As soon the bugle sounded the signal to stop, the violence immediately ended. (Pages 166-168)

Soursouri – Komeshamard [Buffalo Fighting]

Soursouri had some fine buffalos and bukirs, which is what the locals called buffalo calves. Every year, the village would host a buffalo fight, and a huge crowd would gather. Representatives of the authorities would attend, too. One time, 52 years ago, the Kamalents and Gourghigianents buffalos fought near the mulberry trees in Yaz. The vali [governor] of Mezire and the pasha in command of the army detachment came to see it. The owners of both buffalos had been promised that 10 kilas [360 kg/793 lbs] of wheat would be donated to the church of the winner’s village. Both sides had fed their buffalos dzedzadz [cracked wheat] for three weeks, had given them wine to drink, and had bathed them several times each day. Their horns had been sharpened with files and had been rubbed down with oil in order to gleam. Their hoofs had also been oiled, and right before their fight, they were immersed in water for one to two hours in order to cool them down. When the two buffalos were brought out and their skulls first clashed, it was like the sound of thunder. They started pushing each other, sometimes bucking down to their knees to gain leverage. Occasionally, they separated to get a running start and then banged heads again. Blood ran down both of their foreheads.

The owners of the buffalos had agreed on a condition – that old man Gourghigian would not attend the fight. This condition had been accepted because throughout the village, it was believed that the old man had such a gaze that he could even crack stones by using nothing but his eyes.

But when news spread that the Gourghigians’ buffalo was about to lose, the old man ran all the way from the village, yelling his buffalo’s name: “Arab! Let me see your stuff!” The villagers began casting ropes [illegible] to pull away and separate the buffalos. But the vali and pasha ordered them to stop, dismissing any protests about Gourghigian’s gaze.

As soon as Gourghigian arrived on the scene, his buffalo, which had been on the verge of losing and was seeking an escape route, upon hearing the “Arab! Let me see your stuff!”, struck its foe’s belly with its horn and tore it up. The wounded buffalo retreated, and went to sit in the stream, while the Gourghigians’ buffalo also went and sat in [illegible] of the water.

The Kamalenk took their injured buffalo away and slaughtered it outside their threshold. They had made significant preparations, as the owner of the winning buffalo would [illegible] with the maraba [2], but it was also an occasion for mourning. Unfortunately, we missed the feast, and we returned to Hussenig hungry.

Gourghigian measured the 10 kilas of grain and gave it to the church. It was used to feed a large group of people. (Pages 606-611)

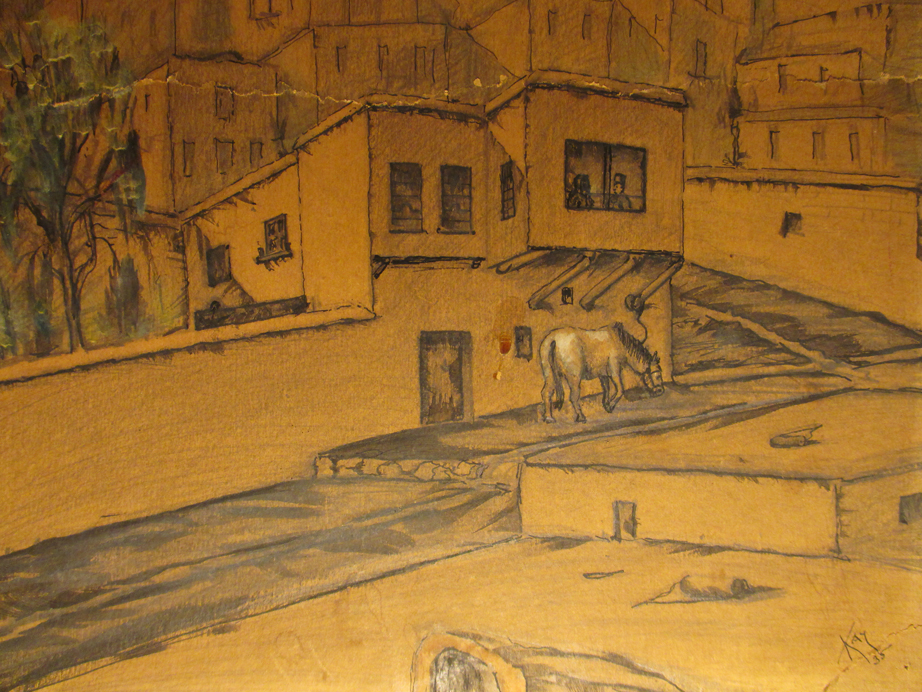

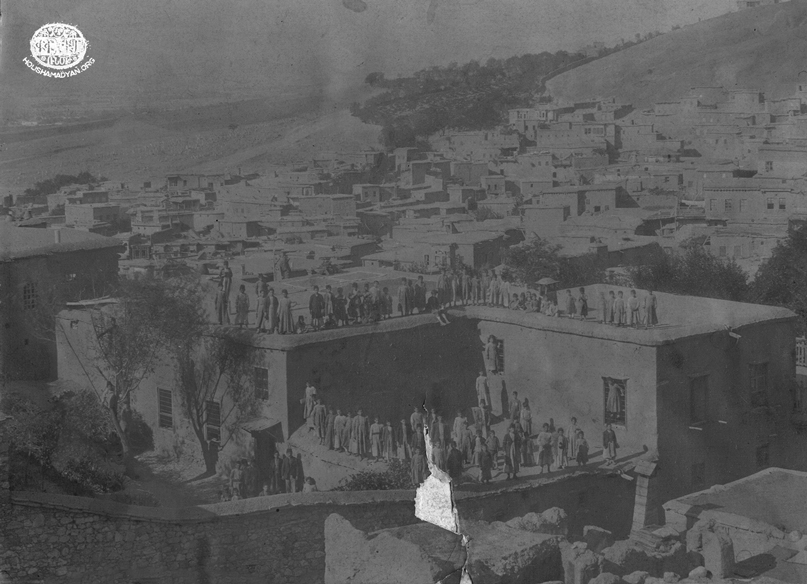

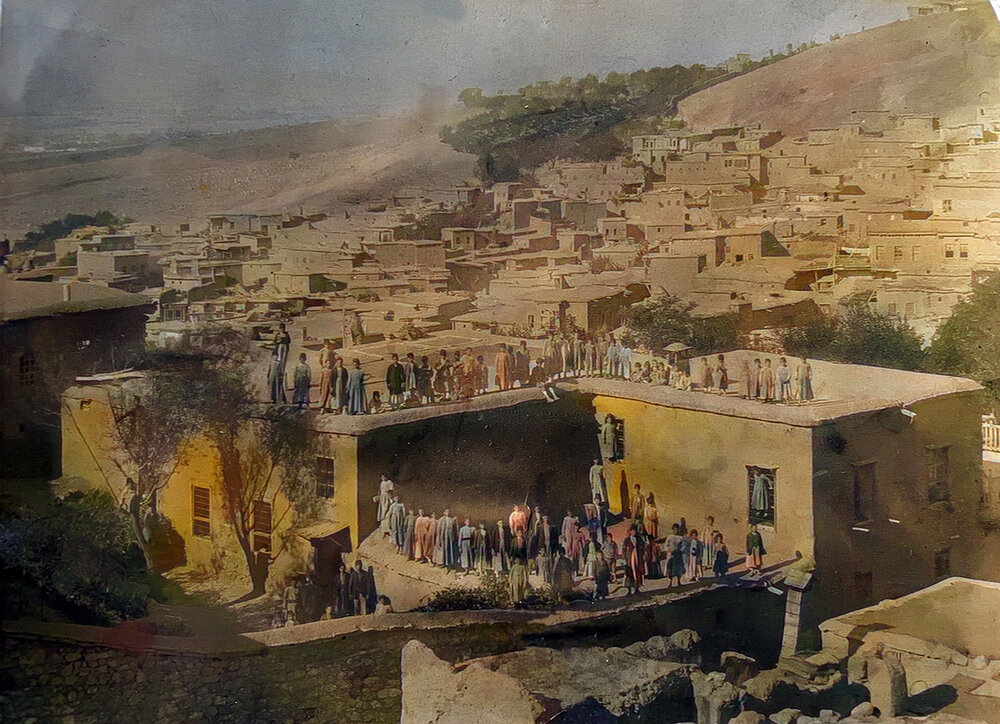

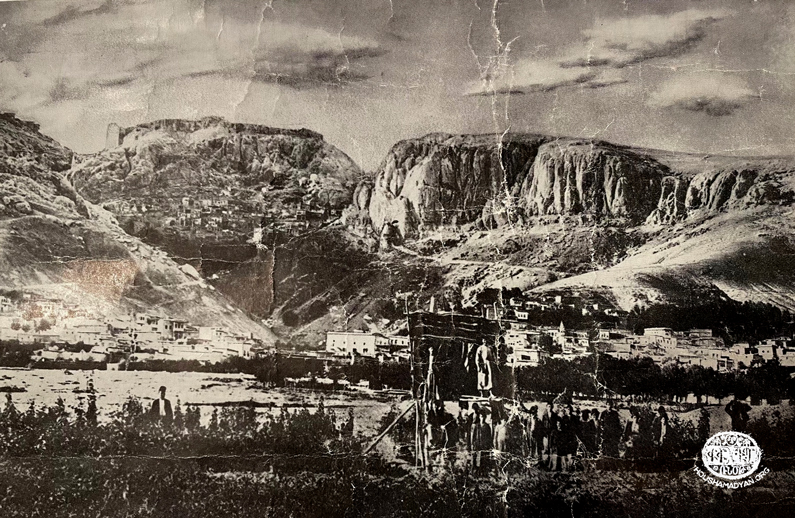

The Yotnag Springs [Seven Springs] in Hussenig. A group of people are visible below the rocks, looking towards the photographer. Photographer: A. H. Soursourian.

This photograph was digitally colorised using Myheritage.com.

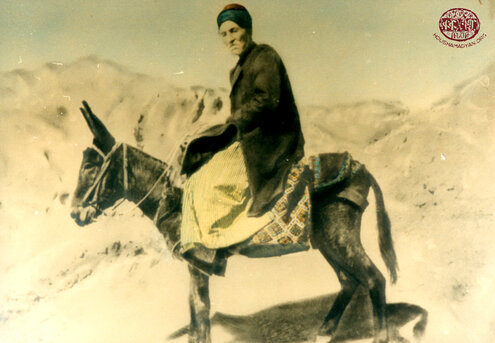

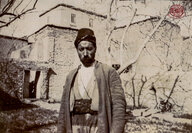

Sadugh Effendi, the Kizilbash Kurdish Agha of the Village of Kaylou [present-day Karşıbağ] (Page 664)

The agha of the village of Kaylou was Khuzulbash Sadugh Effendi, a Kurd. He never harmed Armenians, and always protected them.

Sadugh Effendi’s father had been an accountant in his youth but had later become a trader. He was business partners with my grandfather, Mdghes Oyno or Ovannes Khazhandjian. Sadugh Effendi and his brother, Houso, had been conducting business with my father for many years. They often visited our home and spent the nights there. Members of our family, too, would visit their home. Sadugh Effendi and Houso spoke Armenian as fluently as any Armenian.

My brother, Hadji Agop, had purchased land in Kaylou, and the village’s mill belonged to him and Sadugh Effendi. The two treated each other like brothers. My brother’s wife and children sometimes spent the holidays in Kaylou and stayed with Sadugh Effendi’s family. Similarly, Sadugh Effendi’s wife would come to Mezire and stay with my brother’s family.

Sadugh Effendi had been active in Mezire for 15 years as an accountant when the last deportations began. His brother, Houso, had died by that time, and Houso’s son was the mapouskhana moudour (administrator) of Mezire Prison. When the deportations began, my brother [Hagop] and his son [Haygaz] were arrested, and were about to be taken away and shot. Sadugh Effendi wanted to prevent this, but couldn’t, as my brother was a member of the makhkama (high court), which was the reason he was called Hadji Beg.

That night, Sadugh Effendi and his nephew (the prison administrator, who was also his son-in-law) rescued Haygaz and found him shelter with a Turkish friend of theirs. My brother gave everything he had, including a huge heap of cotton, 500 Ottoman pounds, and all the rugs in his home as a bribe to Hadji Baloshents Mamat Beg, in order to avoid being deported alongside his entire family. Agop Effendi Djandjigian had also paid Mamat Beg 800 Ottoman pounds, as he was a high-ranking official in [illegible]. Only, he sent the bribe two weeks later. This was the Beg’s way of robbing Armenians.

My brother, Djandjigian, and the Armenian Prelate of Kharpert, alongside a large group of Armenians, were taken to a place called Har Oghloun and killed.

After these events, Sadugh Effendi brought my brother’s family to his house, including my brother’s wife, Zmrout; his two sons, Yeprad and Dikris; his two daughters, Maylou and Hasmig; and his son Haygaz’s wife and child. The Effendi told the government that they were his wife, family, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren, so that they wouldn’t be deported or harmed. But his efforts were in vain, as my brother was known to the authorities. The police came and demanded that Sadugh Effendi hand the Armenians over. He insisted that they were his family, but they asked to see his nikah paper (marriage certificate). As he couldn’t produce the document, the refugees were arrested and deported to Izol, on the banks of the Euphrates River, to a Kizilbash Kurdish village.

Sadugh Effendi immediately rushed to the city and obtained a nikah certificate from the mufti, which listed the names of all the Armenians he had taken under his wing. I don’t know how much it cost him to bribe the mufti.

Sadugh Effendi then sent one of his relatives to Izol, so that the deportees could be brought back. This relative reached the village to find that the boys had been separated from the rest, and were being taken to the river, where they would be shot and pushed into the water. He caught up with them and found Yeprad and Dikris, and then also found my brother’s wife, their two daughters, their daughter-in-law, and their grandchild. He brought them all back to Sadugh Effendi’s home in a chariot. Sadugh Effendi protected them until the end of the war, at which point he asked them to return to their homes.

As for our boy Haygaz, he saw that his mother and his entire family were free. One day, a crier announced that a full amnesty had been declared. He wanted to come out of hiding, but the Turk who had given him shelter advised him not to do so. Unfortunately, he ignored this advice, and he and a few other Armenians who had been hiding with Turks came out into the open. The authorities arrested them, tied their arms together, and deported them to Kaklig Tapa, near Kherkhig, where they killed them all. I wrote this to make the point that one can rely on the friendship of a Kurd, but not that of a Turk. (Page 664-668)

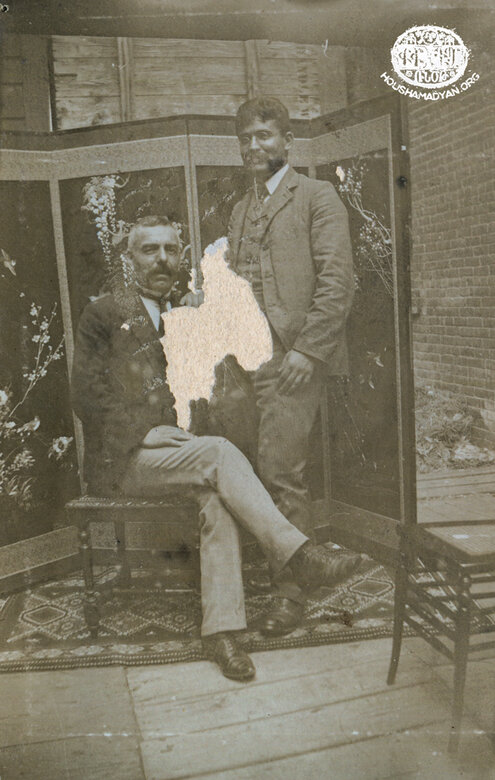

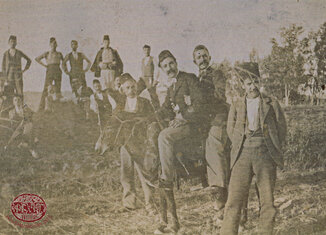

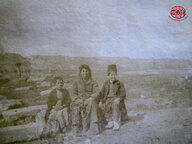

Pilibos (left) and an unknown person, migrants from the Ottoman Empire on their way to the United States. These photographs were digitally colorised using Myheritage.com

The Migration of Kharpert Armenians to America

It was after the massacres of 1895 that Armenians living in America began arranging for their wives and betrothed to join them. This was a result of the government’s decision to bar the entry of these emigrants back into the Ottoman Empire, and to imprison them in coastal cities if they returned. These policies forced Armenian immigrants to send for their wives and children.

In 1900, when the Turks prohibited Armenians from traveling to America altogether, Armenian and Turkish youths, in groups of five to ten, began making their way across the mountains to the coast. They would then bribe the crews of ships to take them to Europe. From there, they would find passage to America.

Kharpert Armenians who had emigrated to America and who had wives and children back in Kharpert began sending for them. Those who were still unmarried spent large amounts of money and implored their parents to find them a wife. The men would send their photographs, which their parents would show to the candidates’ parents, and thus, engagements would be arranged by photograph. Many couples were also from the same village and knew each other. A photograph of the future bride would be sent to the future groom. Sometimes, men would pay for their brides-to-be to travel to America, but upon arrival, these women’s relatives would meet them in New York and marry them off to other men. (Pages 814, 818, 821)

- [1] Pavlukadjonts: This descriptive term is used as a cognomen. Pavluka means factory.

- [2] Maraba: a tenant farmer who did not own the land he cultivated, and who shared his harvest with his landlord.

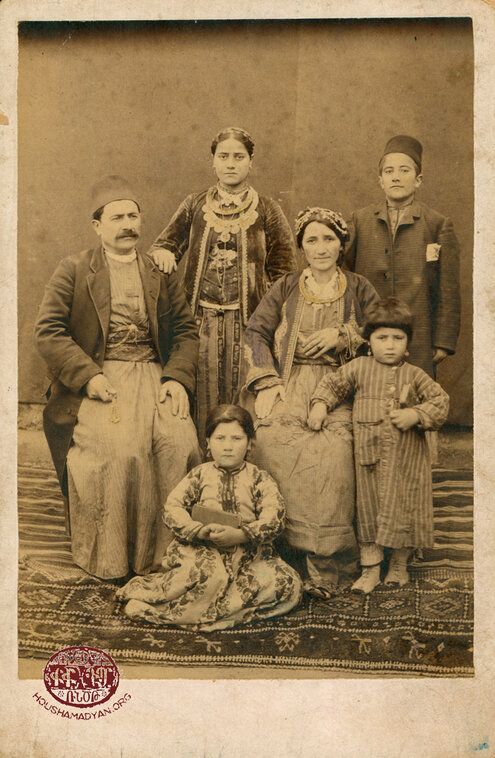

1907, Constantinople or Kharpert. Pilibos and Yeghsa, photographed with their children. This was very likely a family passport photograph taken before their departure to the United States. Left to right: Hayastan, Arthur/Ardashes, Yeghsa, baby Haig (sitting on his mother’s lap), Carl/Khosrov (wearing the fez), John (standing between his mother and father), and Pilibos. The girl on the very right, according to the inscription in the album, is Azniv (Atam’s daughter), a young girl who was cared for by the Kazanjian family. However, there are several indications that Azniv was actually Yeghsa’s half-sister, Takoohi/Queenie Parigian. Elizabeth Kuzirian, who later married Queenie’s brother, Harry Bagdasar Parigian, wrote in a family history that Levon Tahakjian had requested that a wife be found for him. Takoohi/Queenie was proposed as a candidate. According to Elizabeth, Queenie and Mariam Tahakjian, her mother-in-law-to-be, travelled to America together, and the wedding ceremony was held immediately upon their arrival.

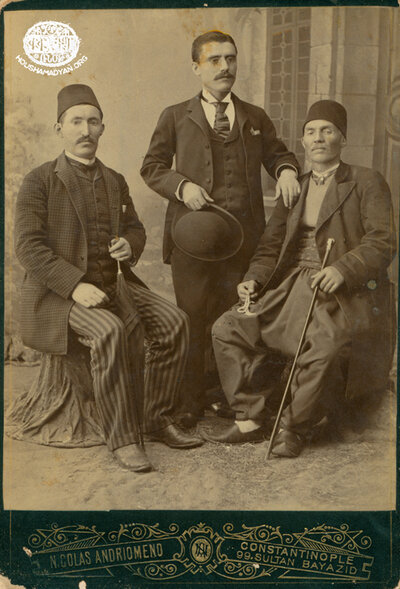

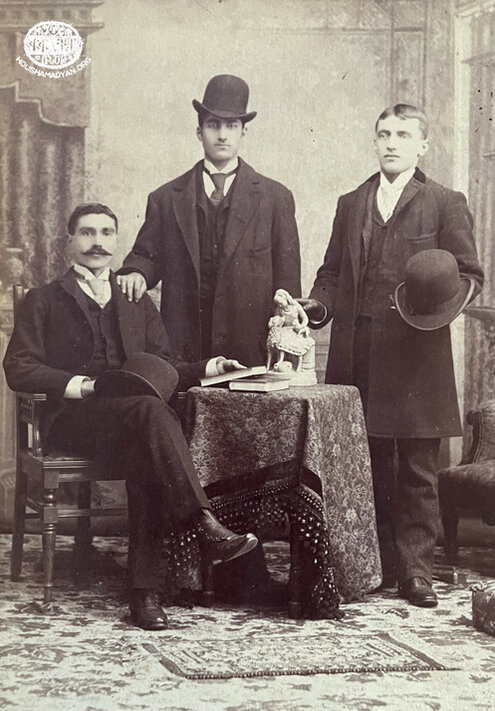

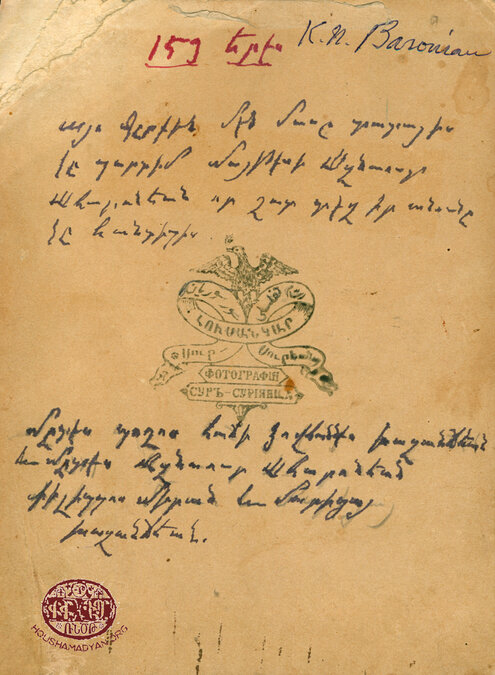

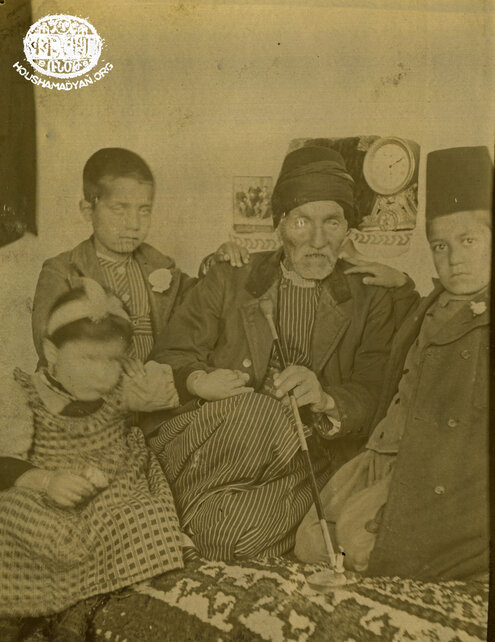

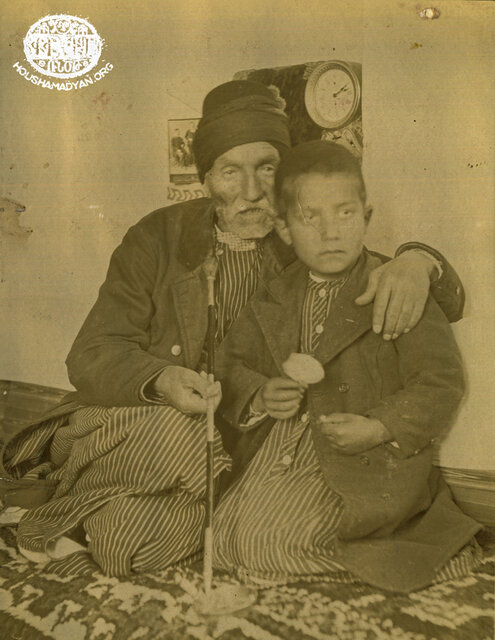

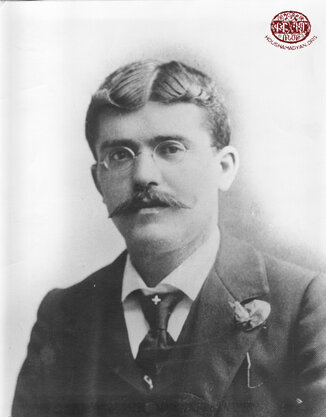

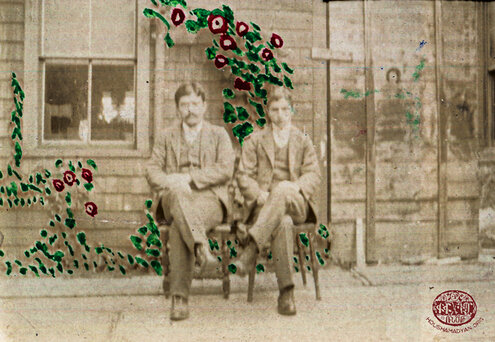

Seated, left to right: Mghdesi Boghos, Hadji Hovhannes Khazanjian, and Meghdes Aznavour Aharonian. The relationships among these individuals are unclear. Probably, Boghos was the son of Hovhannes and his first wife, Mariam Hazarkhan. Aznavour Aharonian may have been the father or grandfather of Hovhannes’ wife, Yeghsapet Khazanjian (nee Aharonian). Standing, back row: Pilibos and his sister Maritza, Hovhannes and Yeghsapet’s children. Standing in front of Hovhannes is his grandson Mihran, son of Hagop. Photographer: Soursourian brothers.

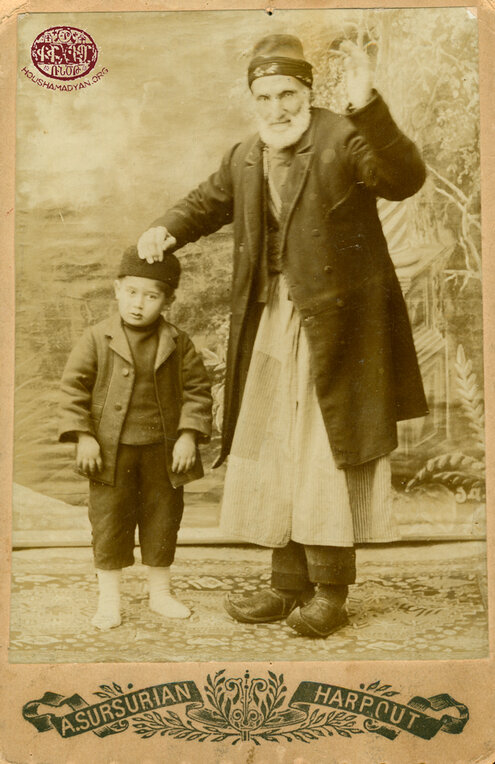

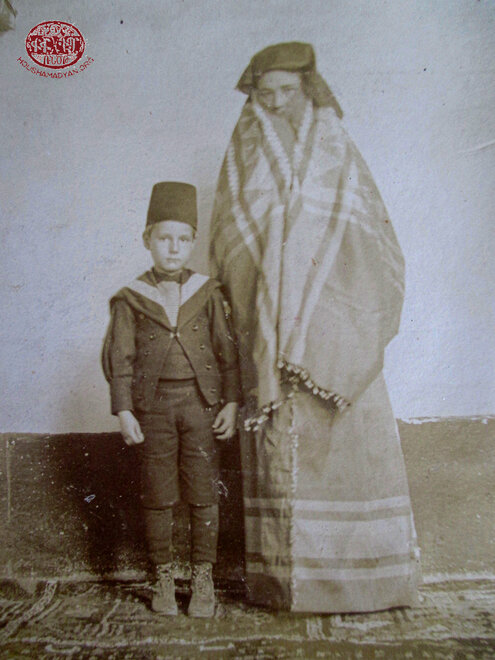

Sargavak [Deacon] Ovan Aghpar (the elderly man) and John Vanderbilt Kazanjian, son of Pilibos Kazanjian. According to Pilibos Kazanjian’s memoirs, when Ovan Aghpar was 20 years old, he was employed as a servant for German General Moltke when the latter spent a short period of time in Harput/Kharpert in the 1830s. On the back of the photograph, Pilibos wrote that the moment captured Ovan Aghpar’s anointing of his son as “A warrior of the Armenian nation”. John “Casey” Vanderbilt later became a professional wrestler before taking up farming. Photographer: A.H Soursourian

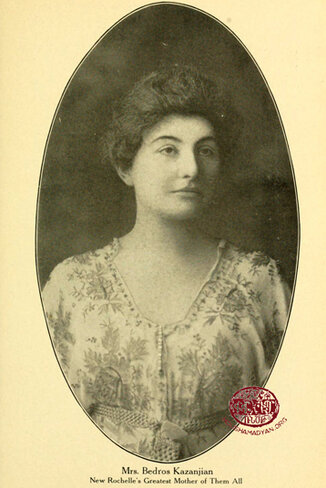

1. Vart S. Harpoutlian (1878-1960). Around 1895, she married the man in this photograph, John H. Kazanjian (1865-1941), brother of Pilibos. John and Vart lived in Newport, Rhode Island, where their first child was born in 1897. When this photograph was taken, Vart was very likely still in Kharpert, while her husband was already in the United States.

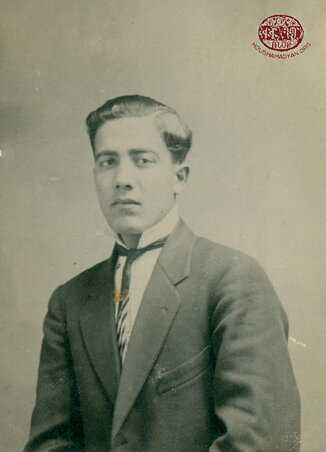

2. Pilibos Kazanjian in Newport, Rhode Island.

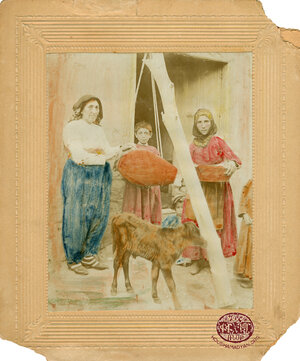

Hussenig, 1904. Left to right: Khachadour Tashjian’s wife and daughter-in-law (names unknown). They are making tan [ayran] in a churn. The others in the photograph are unidentified. Most likely, they were the children of Khachadour’s daughter-in-law. A calf also appears in the photograph. Khachadour Tashjian was nicknamed muhendis (engineer, builder). According to Pilibos Kazanjian, he built vital roads in the city of Mezire (Mamuret-ul-Aziz). We do not know if there was a family relationshipbetween the Tashjians and Kazanjians. The Tashjians may have been cousins of Vart Harpootlian, who married John, Pilibos’ brother. Karl Martin Tashjian-Stone appears to have emigrated to the United States with John and Vart, and was living in their home as of 1900.

This photograph was most likely taken at the funeral of Hovhannes/Ohannes Khazanjian, in 1904, in Hussenig. Hagop, the son of the deceased, is on the left of the coffin, without his fez and with his hand resting on the arm of his father. Pilibos, the other son, is on the right of the coffin, wearing a fez and glasses, and his hand placed on the coffin.

Hussenig. Probably the funeral of Hovhannes/Ohannes Khazanjian, Pilibos’ father, 1904. Pilibos is the man kneeling on the left of the coffin, with his hand on it. The man on the right, also with his hand on the coffin, is likely Pilibos’ brother, Hagop. The man seated next to Pilibos is present in many other family photographs; and the man with his hand on Hagop’s shoulder is probably one of his sons.

Hussenig, 1904. The funeral of Hovhannes/Ohannes Khazanjian. His grandchildren in the forefront, left to right: Khosrov/Carl, Hayastan, and Ardashes/Arthur. Behind the coffin: Yeghsa Kazanjian (nee Parigian), wearing the black veil and with her son, John, sitting on her lap. The two men seated on her left are very likely two of the deceased’s sons. Yeghsapet, the widow, is seated on the right of Yeghsa, at the head of the coffin. Pilibos is standing behind his wife and mother. The man at the head of the coffin with his hand over his heart is likely another of the deceased’s grandchildren, possibly Drtad. Photographer: Soursourian.

In his memoirs, Pilibos Kazanjian tells the story of this watch:

… Someone from the village of Morenig, by the name of Palvutsonts, had been a cook to an old sultan. One day, the sultan summons him: “Ashdji [Cook]!” “Yes, my Lord,” replies the cook. The sultan says, “The eggplants do not taste good.” The ashdji replies, “My Lord, the eggplants are, in fact, poisonous”. The sultan says, “Ashdji, just a little eggplant makes your meals better.” The ashdji replies, “My Lord, a dish with eggplants is like the flower of any meal." The sultan says, “Ashdji, when eggplant is served, it destroys the flavor of the other dishes.” The ashdji replies, “My Lord, that’s because eggplant is mazarat [harmful].” The sultan says, “Ashdji, when I praise something, you praise it more than I; and when I disparage it, you disparage it more than I.” The ashdji turns to the sultan and replies, “My Lord, I serve you, not the eggplants. In whichever direction you spin, I also spin, like a top.” In appreciation for this display of loyalty, the sultan gifted the cook this pocket watch. The [cook’s] son later sold the watch to my father for four mejides. After my father’s death, I inherited it and brought it with me to America. It is a large breast pocket watch… (pp. 387-388).

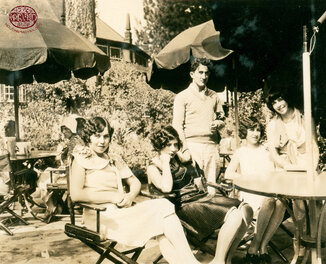

1. The Kazanjian family, photographed in Fowler, California, circa 1908. Seated, left to right: Yeghsa (nee Parigian), Pilibos, and Hayastan standing beside Pilibos. Back row, left to right: Ardashes/Arthur and Khosrov/Carl. Haig is standing in front of his father. John “Casey” is seated in front of his sister. Diana was not yet born when this photograph was taken.

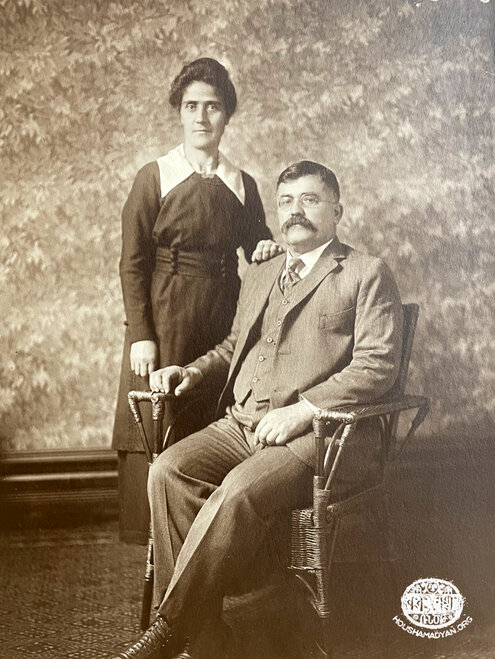

2. Yeghsa Kazanjian (nee Parigian) and Pilibos Kazanjian.