Edward Morris Wistar Archive - USA

Author: Rosemary Russell

Insights into the Second Expedition of the American Red Cross in 1896

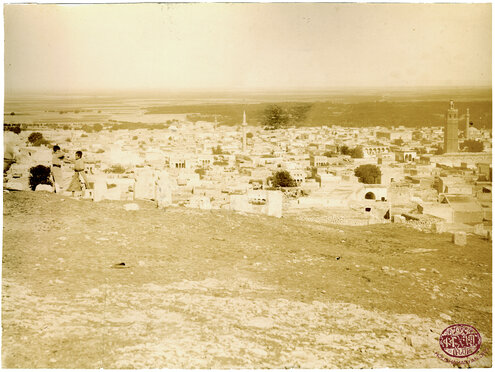

The photographs displayed on this page represent the experiences of American Red Cross Special Field Agent Edward Morris Wistar, leader of the Second Expedition in 1896. [1] All of the photographs come from the Edward Morris Wistar Papers, [2] though several of them pre-date his relief mission.

In late 1895, Edward Morris Wistar received a letter from Clara Barton, President of the American Red Cross (ARC), asking him to join her small team of relief workers [3] heading to Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. The American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was requesting the ARC head up relief to the victims of recent anti-Armenian massacres.

Normally, the ABCFM would have carried out relief work. However, the situation was so critical that its own missionaries could not move about their districts because of continued instability and a devastation so vast as to dwarf their own resources. Over a large swath of the empire, mobs constituted of Turks and Kurds instigated by central authorities plundered Armenian homes and torched their villages. Upwards of 100,000 people had been killed outright. Another 100,000 would die from disease and starvation. Tens of thousands of survivors were left utterly destitute.

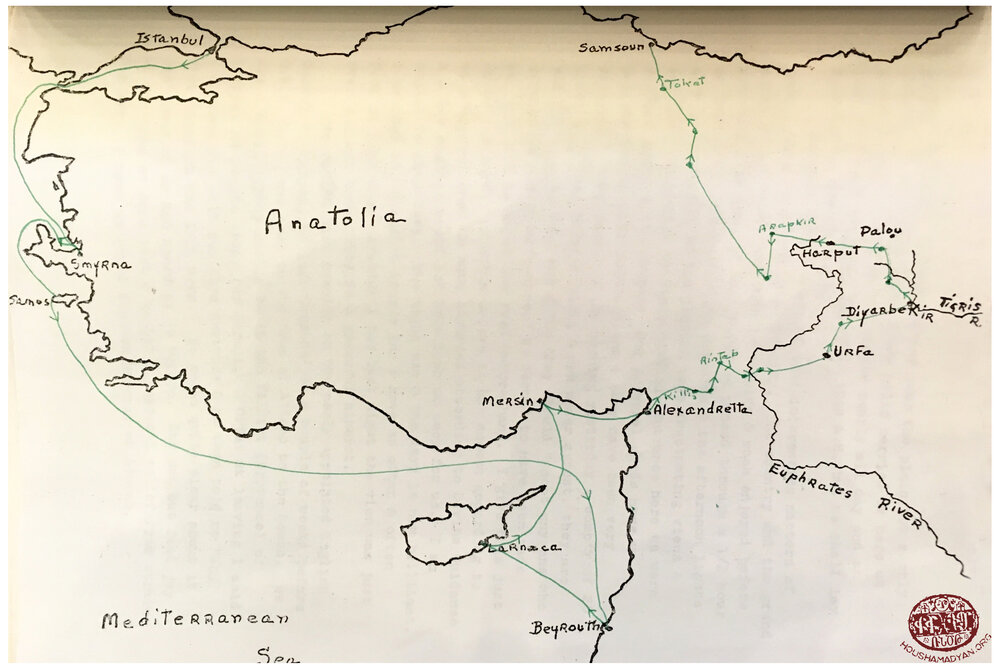

These were the dire conditions into which Wistar, a devout Quaker with experience in humanitarian endeavors, entered when he accepted Barton’s request. [4] On 22 February, 1896, he set sail with Charles King Wood, the two arriving in Constantinople nearly two weeks later. [5] Upon arrival, the men secured their travel papers, hired an interpreter, [6] and purchased relief supplies. Then, they set out for Ayntab by way of Alexandretta/Iskenderun, taking with them specific instructions from Clara Barton that included a directive to avoid any questions of a political nature. [7]

Dr. Julian Hubbell, leader of the First Expedition, met up with Wistar and Wood in Alexandretta, and the three ARC special field agents set off together for Aintab. [8] The relief work there was well in hand. Therefore, after dispensing supplies from the ARC and the Friend’s Mission of Constantinople, a Quaker organization, [9] the three departed for regions of greater need, Dr. Hubbell to Zeytun and Marash; Wistar and Wood to Ourfa, all en route to Harput/Kharpert. [10]

Days before sailing from New York, Wistar would have seen the letter of American missionary Corinna Shattuck in charge at Ourfa published on 17 February in the New York Times. It was dated 7 January, just ten days after the cessation of the massacre in Ourfa, and provided a trusted account of the tragedy befalling the Armenians there.

According to her letter, Shattuck had been for weeks trying to gain permission to travel to Ayntab. It was not until Saturday, 28 December, an hour before the massacre began, that the government granted her request. She heard gunfire signal the start of a slaughter that was a more comprehensive interval of killing and plundering than the previous attack of October. “For days,” she wrote, “the air of the city was unendurable.” She witnessed men dragging away bags of bones and ashes. Bodies were carted off and thrown into trenches. “Literally [nothing] remains,” she wrote. Shattuck took in 300 refugees but had to turn away many others for lack of resources to feed and shelter them. [11]

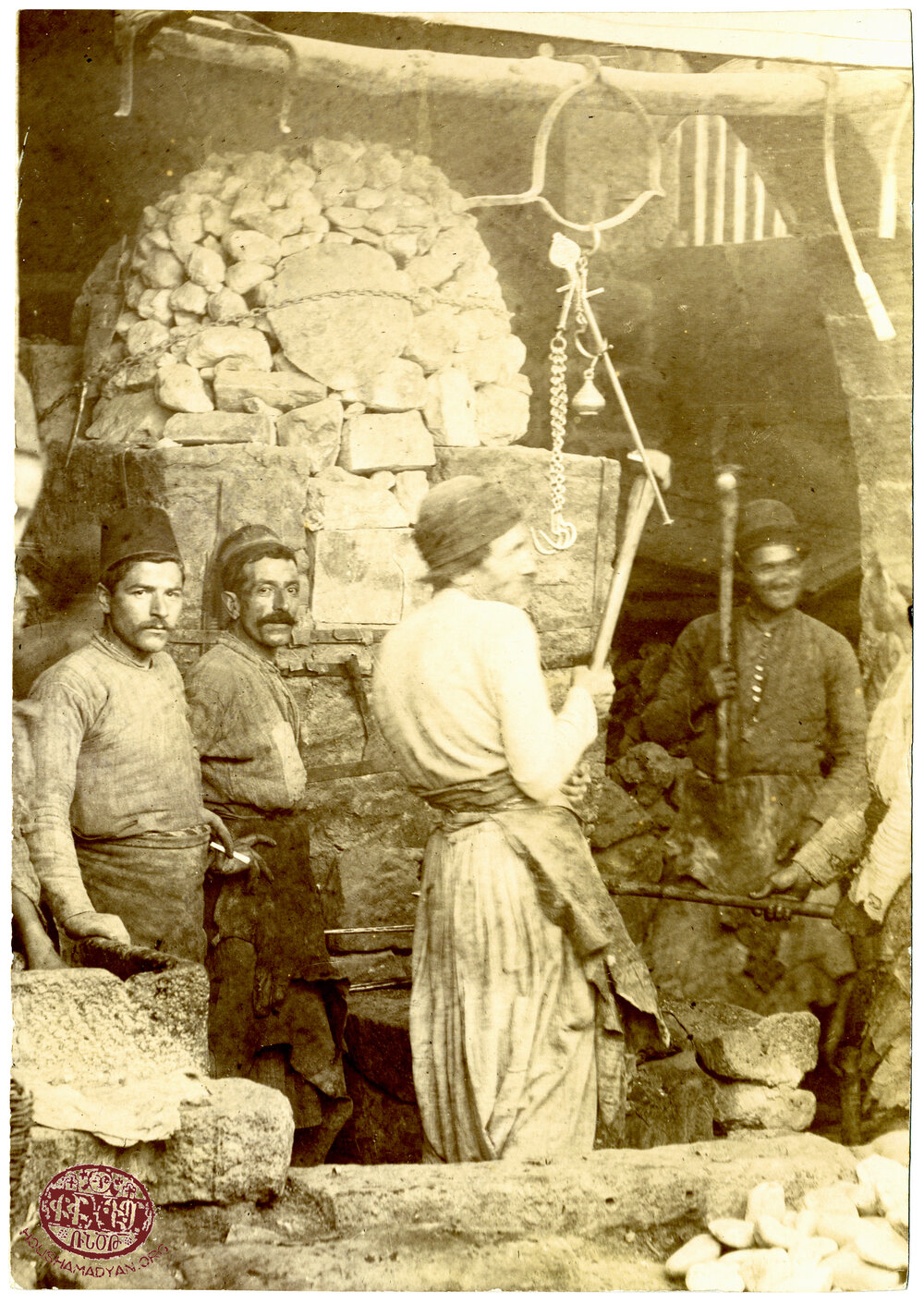

Though the city had suffered a terrible blow, Wistar saw signs of hope when Shattuck gave him a tour of the various industries functioning once again on the mission compound. [12] The most important expense for which she had no funds was copper for the making of vital household utensils. Ownership of copper ware was a matter of survival, especially for families that lived in remote areas. Most households owned at least two pans made locally by copper artisans. One was made for cooking, frying, steaming and boiling food. The other, usually larger, was used to supply hot water for bathing, laundry and cleaning.

Wistar and Wood stayed twelve days in Ourfa, seven days longer than intended. The governor would not let them leave for Harput—their ultimate destination—because their papers had not been stamped for their present visit to Ourfa. Wistar lamented valuable time wasted. His only recourse was to wait. [13]

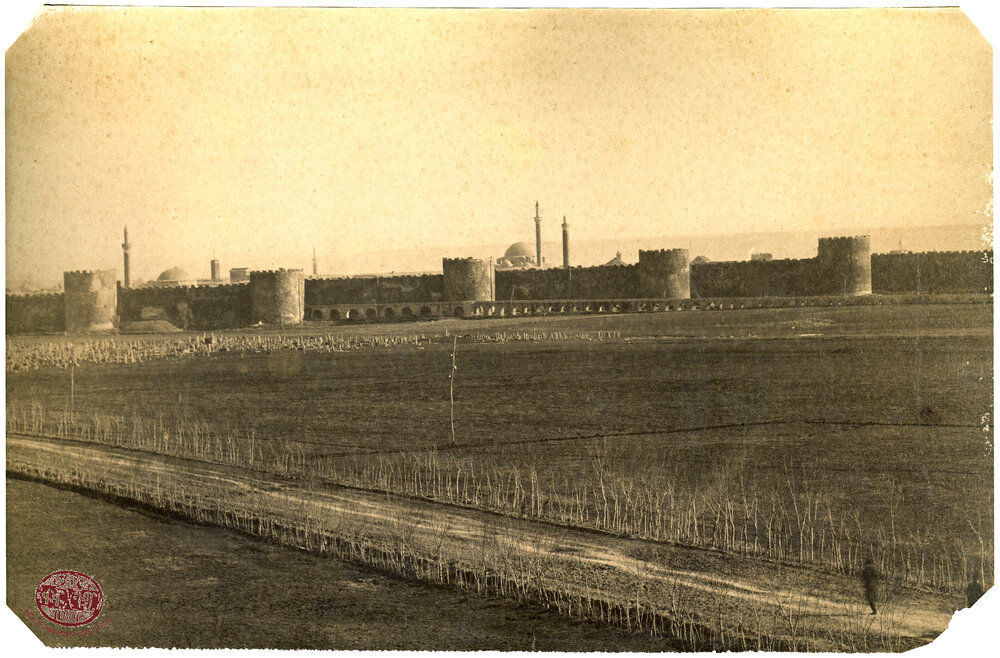

Finally, the Red Cross workers were allowed to continue their journey. They stopped at Diyarbekir for two days as guests of English Consul C. M. Hallward to rest their horses and gather information. Wistar observed that the “villages of Diyarbekir Vilayet have been badly plundered and burnt. The Armenians seem to be either dead or entirely at the mercy of the other inhabitants except so far as the government shall protect them.” [14] He noted “5,000 houses and 25,000 people [had been] plundered”; 2100 killed. [15]

1896. The American Red Cross set up its headquarters at the Pera Hotel in Istanbul where Clara Barton oversaw relief work in 1896. This is a view of the Galata Bridge that spans the Golden Horn in Istanbul. Galata Tower is visible in the distance. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

Leaving Diyarbekir on 27 April, Wistar and Wood made their way to Harput where they met up once again with Dr. Hubbell. An outbreak of typhus and dysentery sent Hubbell to Arapgir. This left the two men to divide the enormous work load between them. Wood traveled to the Palou district and Silvan of the Vilayet of Diyarbekir, while Wistar focused relief efforts on the region of Charsanjak (Peri) and the Kharpert Plain until his departure for Constantinople on 3 July.

American missionaries in Harput had collected data for a detailed report of the staggering losses in that city and surrounding villages. [16] The death toll in January 1896 stood at 7,423. Of those, five thousand had been killed; another 1,000 had succumbed to hunger and exposure. Over 300 people had been burned alive and more than 400 slain in fields and on the road. The wounded numbered 2,000. About 10,000 houses were burned and 108 schools, churches and monasteries destroyed. The report includes the following statistics: 4,643 forced conversions, 973 women raped and 345 forced to marry Turks and Kurds. According to the missionaries, 29,804 survivors were destitute. [17] “Generally, not a rag, not a particle of food, not even a [dish] has been left […] windows and doors have been carried off.” [18]

Wistar explained the “urgent need” in Charsanjak for basic necessities, farming tools, implements and seed, as well as cash to be used to restart businesses. This was not a matter of purchasing items but of manufacturing them. Providing clothing and bedding meant buying raw cotton and hiring workers to first turn it into thread. As thread, it would go to weavers who wove on looms recently replaced by the Red Cross. From the looms, the fabric went to cutters, and from cutters to sewers who were provided with needles, thread and thimbles. The shirts and pants (salvars) were then distributed to the neediest that had been identified by a local committee of Armenian Protestants and Gregorians.

This method used by the ARC to jumpstart local economies provided employment to the destitute who then had a little money to purchase food. Blacksmiths and coppersmiths were put to work making tools, farming implements, and household utensils from raw iron and sheets of copper. Wistar reported distributing tools to approximately 150 artisans and cash to re-open shops. Two hundred oxen, many plows, tools and implements were made available to local farmers. Purchase of wheat enabled bread rations to be given out daily. At the end of his time in Charsanjak, Wistar observed that the bazaars of Peri had been stimulated and that economic conditions had improved greatly. He then turned his attention to Harput.

On the fertile Kharpert Plain, a great crop of wheat waited to be harvested. Armenian farmers were without harvesting tools and the blacksmiths without iron. Again, Wistar went to work securing raw materials. It was essential that the current crop be saved, for there were thousands starving. It was equally important to ensure planting for the next growing season. In his report, Wistar listed the successes of his work in Harput and its surrounding villages with impressive numbers of active artisans, replenished livestock, tools for planting and reaping, clothes, beds and bushels of grain.

No date. Somewhere between Harput, Ayntab, and Diyarbekir. Armenians lost the ability to till, plant and harvest when their equipment and animals were taken in the course of the 1895 massacres. The American Red Cross sought to provide them with the means to plant and harvest, hoping to avert a famine. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

Edward Morris Wistar made a noble sacrifice in his role as a field agent of the ARC, and he left a rich record of his experiences in his journal and correspondence. The accomplishments that he listed in his official report were infinitesimal compared to the ongoing misery. Of this he was painfully aware. But the position of the ARC, under Barton’s direction, forced Wistar to acknowledge the tragedy that had necessitated the relief mission, while effusively thanking the authorities for making relief work possible (in spite of their role in fomenting the violence). The purpose of the report served to provide quantifiable results for the many who had donated funds toward the relief effort and to avoid assigning blame or eliciting sympathy.

In truth, Wistar, who had visited several towns and villages on his way to Harput and had witnessed the conditions of the Armenians firsthand, descended into despair in May at Charsanjak as a result of the seemingly unending obstacles he faced. At Harput, he met with continued hindrances. [19]

His journal reveals several problems that prevented or delayed his carrying out intended work. Local authorities interfered with recipients of aid after Wistar had overseen distribution. He wrote, “My work has been again made more difficult and uncertain by lack of any confidence in the government and by reported interference with the people after they have received aid.” [20]

He was repeatedly denied permission to visit outlying villages to assess conditions. “[Governor] still defers my visit to villages,” he noted, then adds, “I have reluctantly given up visiting villages […] He [governor] was very kind, but I am debarred.” [21] Days later he writes, “It seems little matter in what way one tries to work, stumbling blocks are presented.” [22] Adding to his frustrations were authorities preventing the distribution of essential tools. [23]

An editorial in Missionary Herald decried such subterfuge and time wasting when it was learned in April that there had been a delay in necessary paperwork for members of the relief expedition. “Though thousands are starving, there is no haste […] The delay will undoubtedly cost a vast number of lives.” [24]

As if all of that were not enough, Wistar’s interpreter, who caused him a lot of frustration, was not trusted by the Armenians in Harput. [25]

The hardship of travel in the interior, dealing with insincere local authorities, an absence of a knowledge of the culture and the language, a problematic interpreter, [26] and the sheer numbers of Armenians who crowded at Wistar’s door begging for work [27] were important details he was not allowed to include in his official Red Cross report. A clearer, more accurate understanding of the ARC Second Expedition in 1896 is available among the papers of Edward Morris Wistar.

1) Detail from the panorama of Ayntab above. The Surp Asdvatsatsin (Holy Virgin Mary) church can be seen with the dome still under construction. Works began on the dome in 1893. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

2) This photo shows the same Surp Asdvatsatsin (Holy Virgin Mary) church in Ayntab after construction, the dome is clearly visible. The shot is from a different angle. (Michel Paboudjian collection, Paris)

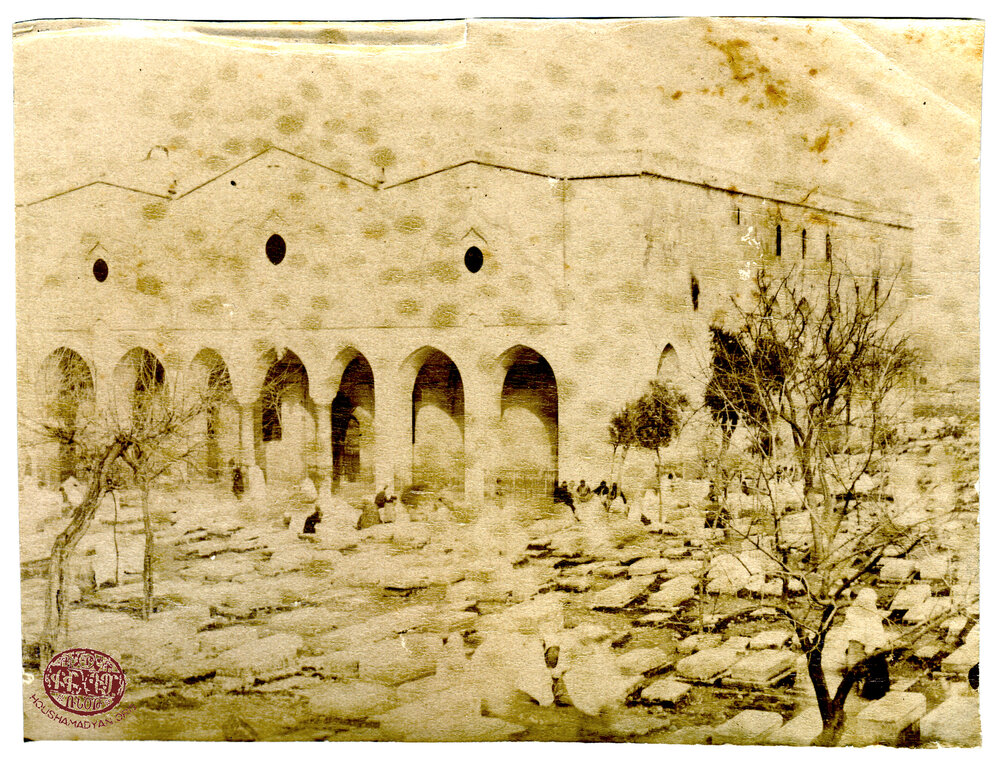

No date. Surp Asdvatsatsin (Holy Virgin Mary) Armenian Church and its Armenian cemetery (in foreground) in Ourfa. This photograph was published in 1897 in the Missionary Herald to identify the spot where so many Armenians were killed in December 1895. The women in this photograph, taken some time before the massacre there, appear to be maintaining the tombs of loved ones. A group of men is seated nearby. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

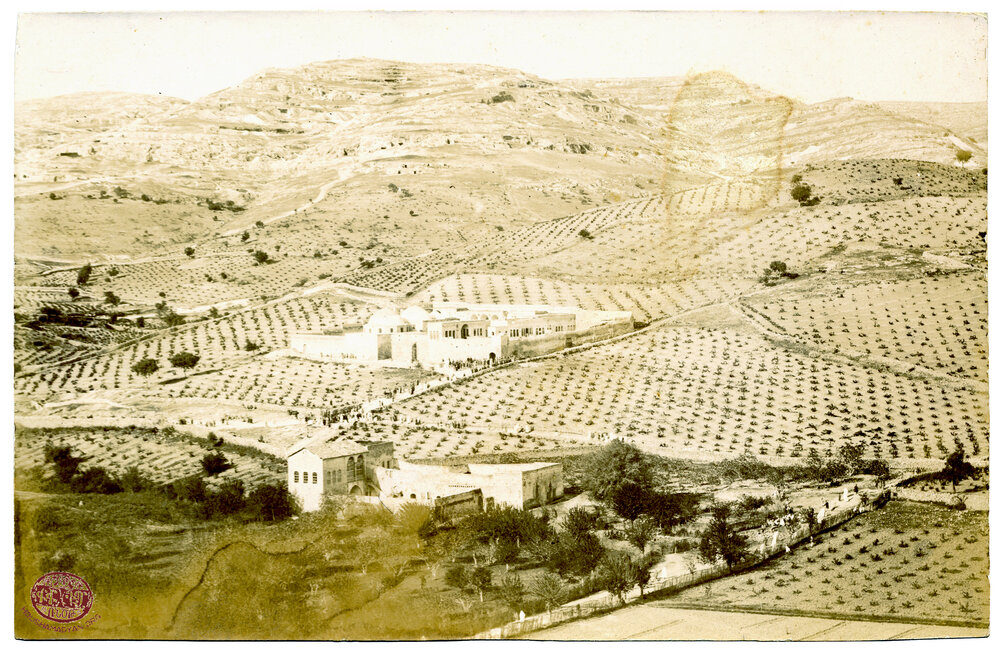

No date. A mid-day celebration brings Armenians streaming to Sourp Sarkis Monastery located one kilometer to the southwest of Ourfa. Wistar likely received this photograph from Corinna Shattuck, missionary at Ourfa. The monastery property included the garden and trees surrounding it. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

1) No date, Ourfa. The scale of the 1895 massacre in Ourfa left thousands orphaned. Wistar marveled at the strength of American missionary Corinna Shattuck with whom he corresponded over the following years. In a letter dated in 26 Aug, 1896, among her concerns was the coming winter: "Winter stores of cereals, garments, shoes, coal, kerosene, where is it to be found?" She also wrote that 3,335 orphans had received garments. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

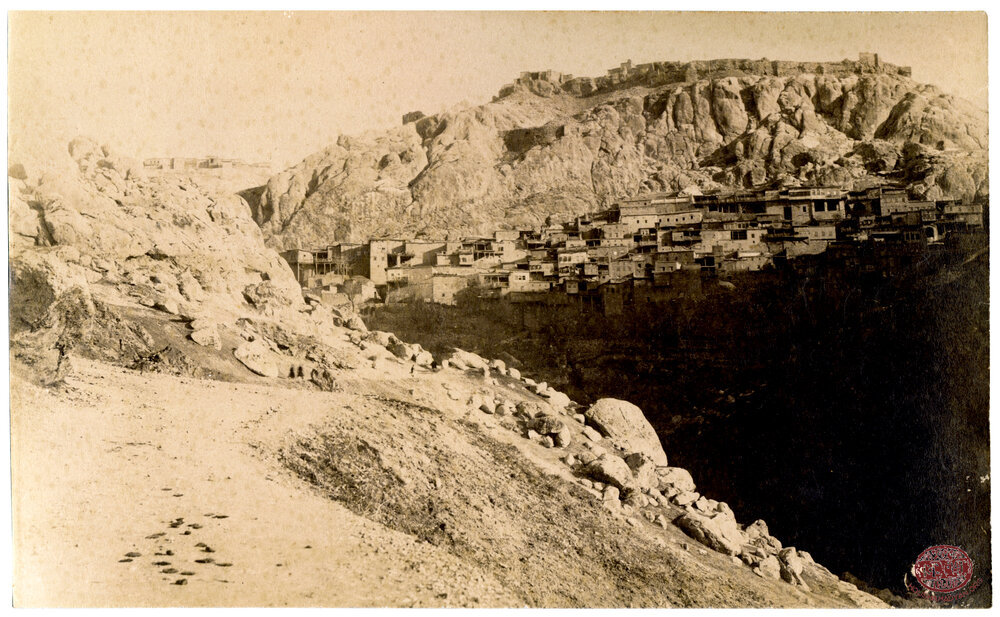

2) No date, Ourfa. The fort and its columns. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

January 18, 1898, Ourfa. German missionaries established this temporary orphanage at Masmana, a rug factory. The boys in the front are orphans who had been moved from St. Sarkis Monastery where they had been living since the massacre. At Shattuck's request, Wistar agreed to support some of these children. She sent him this photograph with a letter in 1898. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

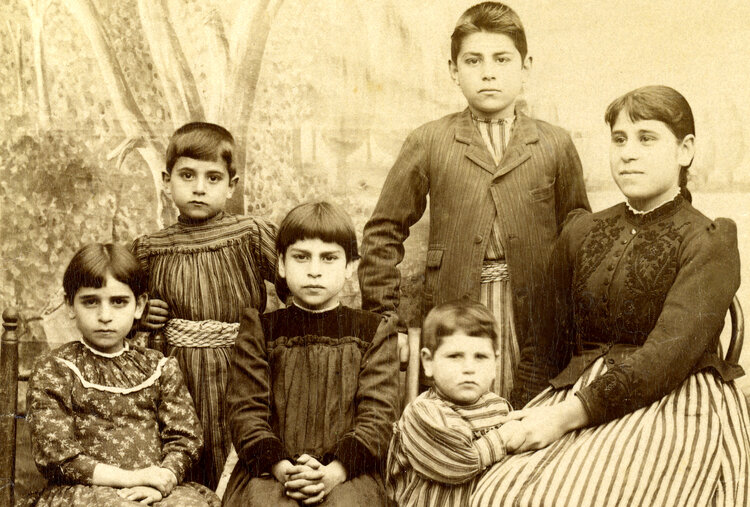

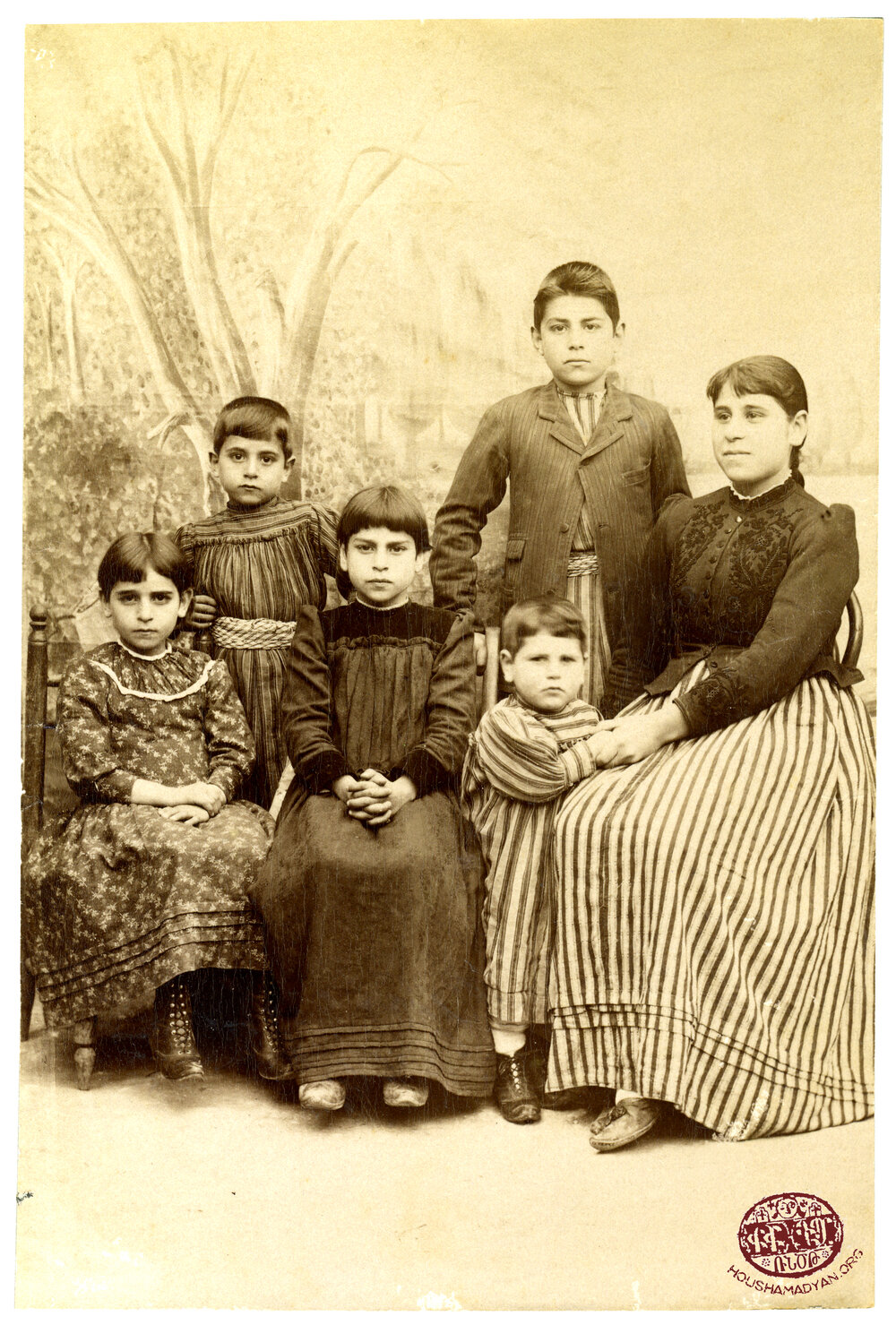

1896, Ourfa. These are the six children of Pastor Hagop Abouhaiatian who was killed in Ourfa during the massacres of December 1895. (Their mother died before this time.) The children were taken to a local mosque but soon rescued by American Board missionary Corinna Shattuck. Badveli Abouhaiatian studied at Bebek Seminary (Istanbul), as well as in Germany and the United States. He pastored the Protestant church in Ourfa for 25 years (1871-1896). (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

1896. The walled city of Diyarbekir where Edward Morris Wistar and Charles King Wood spent two nights en route to Harput from Ourfa. Crenated fortification walls and towers with the aqueduct running alongside it to supply the city with water from the hills. The Muslim cemetery within sight of the minarets inside the city. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

1) 1896, Diyarbekir. The man in European clothes standing with hands in pockets and staring at the photographer is the Red Cross volunteer Wistar. Three Turks enjoy their afternoon tea with their server standing by. Behind them are three wicker baskets designed to harvest olives. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

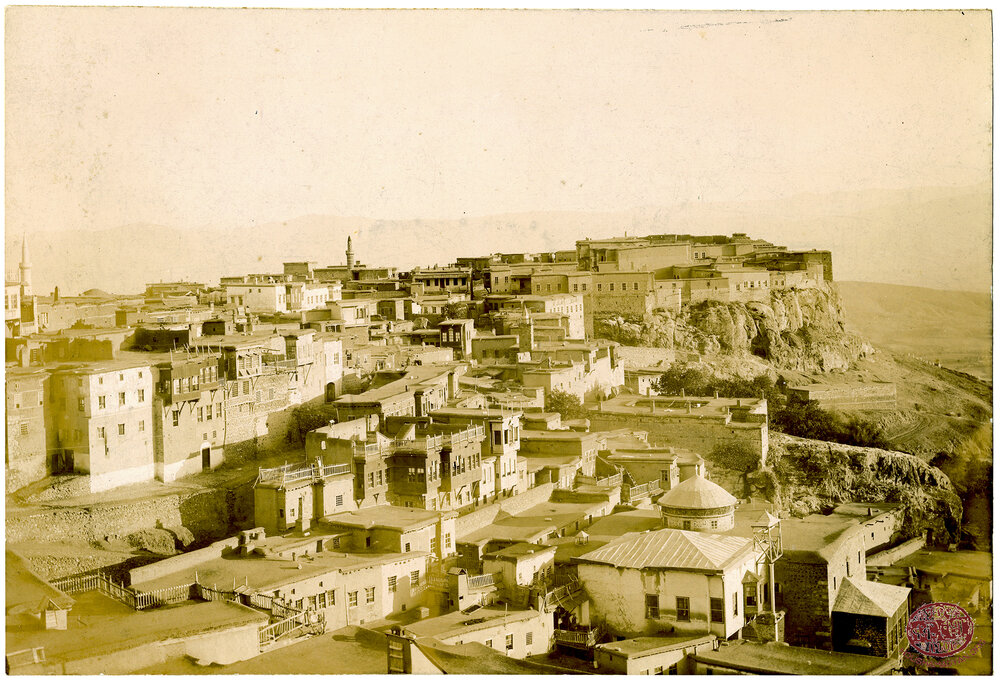

2) April 1896. Inside the ancient walled city of Diyarbekir. Having left Ourfa to journey to Harput, Wistar and his party stopped at Diyarbekir for two nights to rest their horses. They were guests of British Vice-Consul C.M. Hallward. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

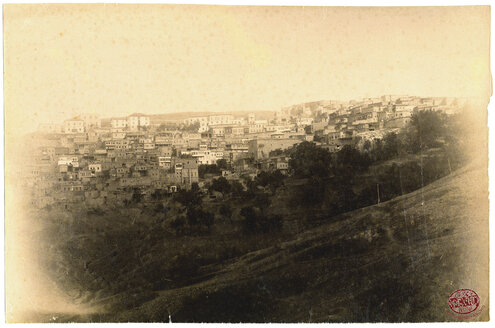

1) No date. Upper Quarter of Harput. The white buildings in back are Euphrates College. St. Hagop Armenian Church (with the dome) is in the center. Wistar stayed with the American missionaries during his time in Harput. Only four of their 12 buildings were not burned during the 1895 massacre. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

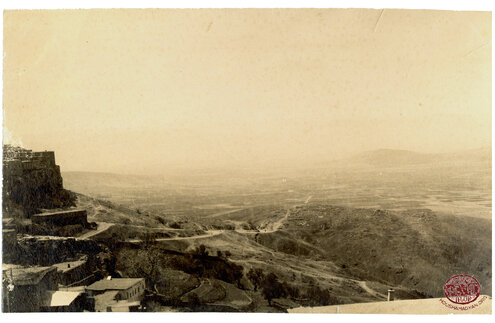

2) C. 1896. The Harput Plain below the city of Harput. "We look out at night from our refuge on this mountain top and see the lurid flames and rising smoke from at least 25 villages" (American missionary O. P. Allen, Harput, 14 Nov, 1895). If Wistar did not take this photograph, he certainly took in this view that includes what appears to be a desecrated cemetery in the distance. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

No date. Upper Quarter of Harput. The white buildings center along the ridge are Euphrates College. The dome of St. Hagop Armenian Chruch is visible on the far right. In January 1896, Dr. Gates, president of the college wrote, "Our buildings are burned, our students are so impoverished." [Letter to Mr. Davis, 8 Jan, 1896. ABCFM Microfilm, Archives of the Billy Graham Center, Wheaton IL] (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

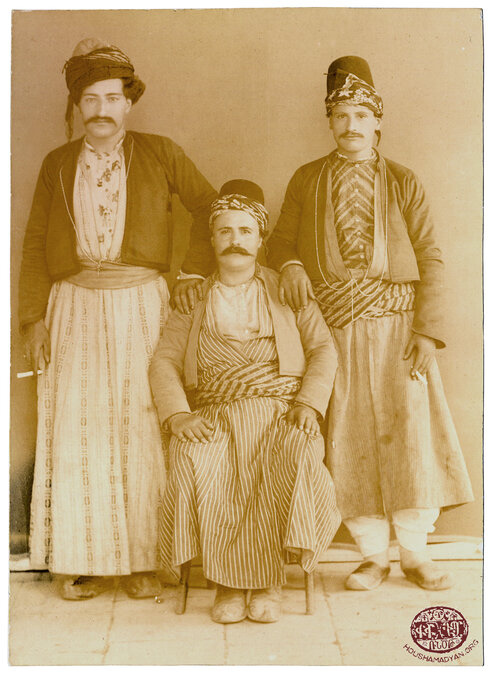

1) C. 1896. Armenian merchants. Likely taken somewhere between Harput, Ayntab, and Diyarbekir. The American Red Cross enabled Armenian merchants to re-open businesses by supplying inventory and creating employment opportunities among Armenian survivors. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

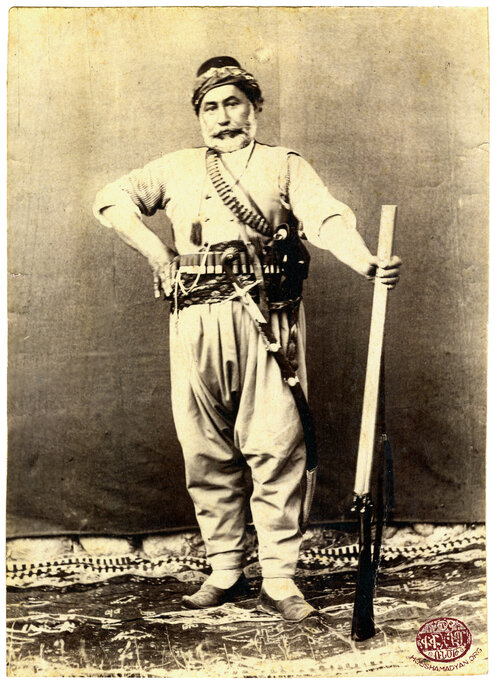

2) 1896. An Armed Kurd. This photograph was taken during Wistar's travels inside the Ottoman Empire. He observed in his journal that "Turks and Kurds through Charsanjak are usually fully armed with guns, pistols, sabres, daggers and knives, especially when they are traveling." (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

C. 1896. Armenian blacksmiths. This photograph was taken somewhere somewhere between Harput, Ayntab, and Diyarbekir, probably during Wistar's time there. The American Red Cross provided raw materials and purchase orders to blacksmiths. Not only was it meant to stimulate this sector of the economy, farmers needed tools to harvest the current crop and stave off a famine. (Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA)

Special thanks to Sarah Horowitz, Head of Quaker & Special Collections at Haverford Libraries and to Dr. Susan Waller, Director of Curriculum & Prof. Dev./Media Center Specialist at The Christian Academy, Brookhaven, PA.

- [1] See America’s Relief Expedition to Asia Minor under the Red Cross, Washington D.C., 1896.

- [2] Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

- [3] Clara Barton had intended on taking a team of eighty people. Because of tensions brought about from stories published in the American newspapers and the response of the Ottoman government in denouncing any ARC relief to Armenians, she was forced to severely scale back her team to include her small staff in Constantinople and four men to serve as field agents.

- [4] Edward Morris Wistar and Dr. J.B. Hubbell, leader of the First Expedition in 1896, had served with the American Red Cross after a hurricane in South Carolina in 1894.

- [5] Charles King Wood, who would become a renowned artist, had recently returned from art school in France. Wistar tapped him as a special field agent after Clara Barton instructed him to bring along another volunteer.

- [6] Wistar hired Michael Topouzoglu as his interpreter.

- [7] List of Tasks, Box 1, Edward Morris Wistar Papers, Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

- [8] The ARC workers passed through Kilis just days after the massacre there. Wistar reported being taunted “by an irresponsible mob” as they entered the town. Because their supplies was on its way to Aintab, they promised to send back medical as well as other badly needed supplies, according to Dr. Hubbell’s report (See America’s Relief Expedition to Asia Minor under the Red Cross).

- [9] Dr. and Mrs. Gabriel Dobrashian opened Friends of Constantinople, a medical mission to the Armenians, in 1881. A school was later added.

- [10] Though Wistar’s report quickly passes over the details of his visit to Ourfa, the impact of his time there is evident in the collection at Haverford, which includes at least 120 pages of correspondence with American missionary Corinna Shattuck.

- [11] “Three Days of Butchery,” New York Times. February 17, 1895. Web.

- [12] Edward Morris Wistar Papers. 13 April, 1896. Box 1. Letters of E. M. Wistar, Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

- [13] “It is pretty difficult for me to be delayed day after day by the slowly moving machinery.” Wistar Papers, Apr 1896.

- [14] Wistar Papers 26 Apr 1896.

- [15] Wistar Papers 26 Apr 1896.

- [16] Statistics of the Recent Outrages in the Harpoot Vilayet, 10 Jan 1896. American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions Archives, 1810-1961 (ABC 1-91). (Microfilm in the Archives of the Billy Graham Center, Wheaton, Illinois.)

- [17] Harris Rendell visited stricken regions in 1896 and made an observation that reflects on the burden of caring for the tens of thousands left wounded, ailing, and impoverished: “What makes Ourfa so much better able to make a fresh start than other places is no doubt that so many were killed outright […] (138-9).” Harris, J. Rendell and Helen B. Harris. Letters from the Scenes of the Recent Massacres in Armenia, London, James Nisbit & Co,. 1897. Missionaries in Harput reported survivors voicing a wish that they had been killed, so grim was their plight in the aftermath of the massacres.

- [18] Barnum, Rev. H. N. (1896), “The Outlook in Turkey.” Missionary Herald, 92, p. 147. Web.

- [19] Barton received a letter from Wistar in Harput. She describes him as “hopeless about the future for the Armenians.” Clara Barton Papers, 16 June, 1896.

- [20] Wistar Papers, 9 June, 1896.

- [21] Wistar Papers, 17 May, 1896.

- [22] Wistar Papers, 21 May, 1896.

- [23] “Wistar finds trouble getting out his tools. The authorities of Harpoot mistrust [Armenians]. Clara Barton Papers, Diaries and Journals: 1896, Jan-Sept. 14 May, 1896. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. June 6, 2017. Web.

- [24] Editorial Paragraphs. (1896). The Missionary Herald, 92, p. 142. Web.

- [25] “Committee jealous and distrustful of my interpreter.” Wistar Papers 22 May, 1896.

- [26] Besides the Armenians’ objections to the interpreter, Wistar recorded several situations in which he questioned Topozoglu’s competence and work ethic.

- [27] Wistar Papers 22 May, 1896. See Wistar’s journal for several references to problems he faced in May and June.