Chakè Matossian Collection – Brussels

Photographs from the Chamlian and Garabedian families (Geyve), and portraits of other Armenians photographed before the Genocide

Author: Chakè Matossian, 09/02/2021 (Last modified 25/08/22) - Translator: Simon Beugekian

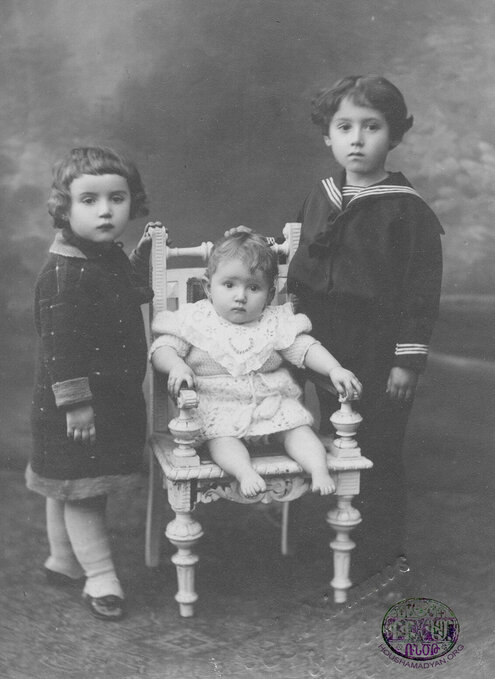

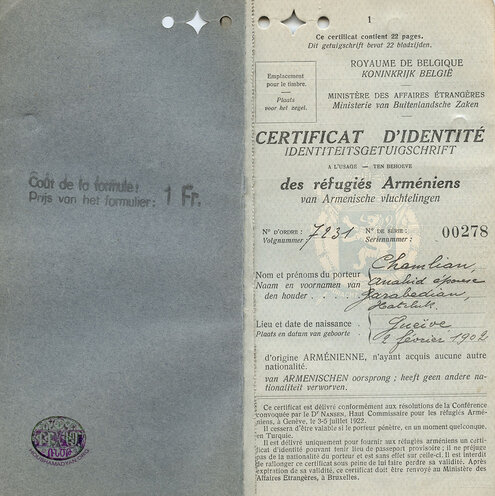

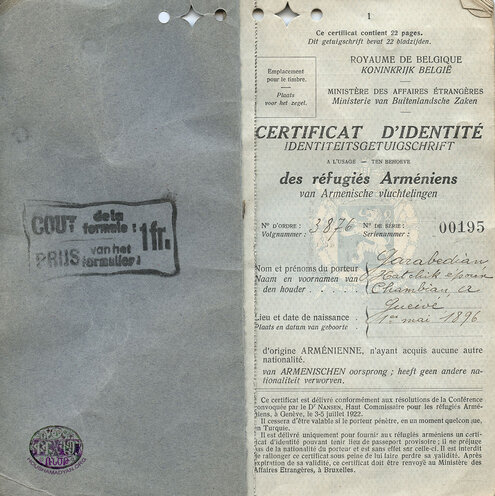

Many of the photographs presented on this page were found in two albums kept in a closet, while others were stored in a box. They pertain to the two branches of the maternal side of my family, namely that of Anahid Chamlian/Shamlian, my grandmother, born in Geyve (southeast of Bursa) in 1902; and that of Khachig Garabedian, my grandfather, who was probably also born in Geyve in 1896 (as stated in his Nansen Passport). Many of the individuals appearing in the photographs are unknown to me, but I believe that it is important that the photographs be shared, given their historical value. Among the notable features of the photographs are the décor and arrangement of the subjects (even when it’s only the décor of the photographic studio), their clothing, their accessories, their positions, their poses, as well as the contemporary styles and trends that can be identified. These details attest to the choices made by the photographic studios. One of these studios was that of Nikolai Andreomenos, which was well-known at the time. The photographs also convey a specific mood. For example, the collection includes photographs of three children who are pictured with striking expressions that betray early maturity, with their legs gracefully positioned, and with gazes of youth in the process of discovering the world.

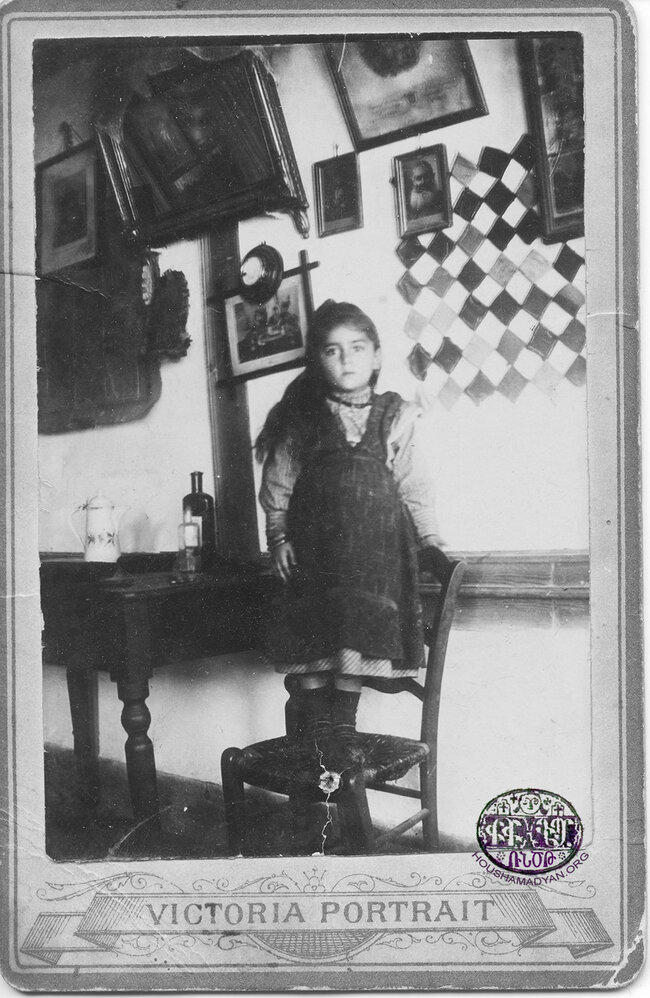

The photograph of Anahid Chamlian was taken when she was seven years old. She is pictured standing on a chair, perhaps to improve the lighting in the photograph or to stand closer to the framed photographs, barometer, and clock on the wall. In any case, the photograph was taken before 1915. I was struck by the seriousness of the expressions of the children in the photographs from this period. In my opinion, this adds to the power of these portraits, accentuating the melancholic nature of the attempt to capture a moment in time, to capture the futility of human condition that the children seem unconsciously aware of. Perhaps the custom of obligatory smiles, or more generally of overt joy in photographs, can be attributed to the Americanization of culture and prevailing advertising methods. Whatever it is, the young Anahid Chamlian, with her pensive pose, manifests the decor of her surroundings, her attire, her bracelets, and the pendant hanging from her neck. When I see this photograph of my grandmother at such a young age, I remember a heartrending story that she used to tell: her father had brought her a doll from Constantinople that she cherished. One day, a prominent Turk (the village chief?) came to visit them and let it be known that his daughter would love to have the doll. Anahid’s father handed it over to the visitor. Anahid Chamlian’s parents fell victim to the Armenian Genocide.

Anahid Chamlian was the younger sister of Souren Chamlian, the founder of the periodical Marmara of Constantinople. Souren’s family emigrated to Canada. Souren and Anahid’s parents were Garabed Chamlian and Aghavni Upikian. Garabed was the son of Hadji Ohan Chamlian and Serpouhi Pilibossian.

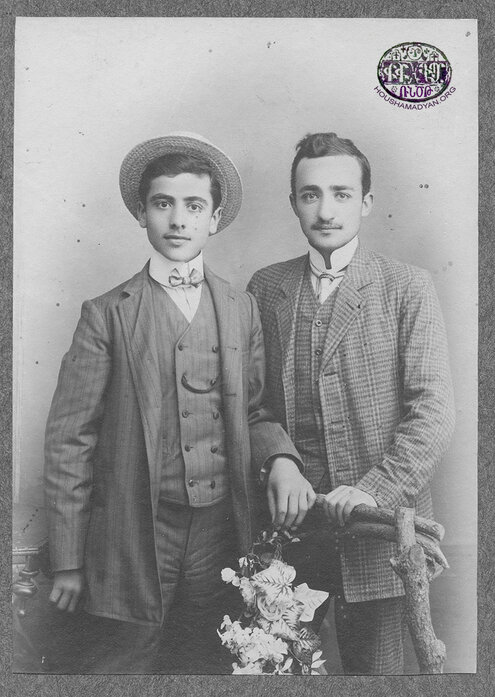

Souren Chamlian was a childhood friend of Khachig Garbedian’s, Anahid’s future husband. Both of their families were engaged in the silk trade. Souren and Khachig appear together in the group photograph of the pupils of Constantinople’s Nor Tbrots [“New School”], taken during the 1912-1913 schoolyear. In the photograph, the large building of the Nor Tbrots appears beautiful, impressive, and alive with history. In the well-lit courtyard, the children and adolescents seem very serious, although traces of grins can be detected in some of their expressions. They are all well-dressed and are posing alongside their teachers. One wonders what happened to them all…

Other photographs taken just before the Genocide include those of the women and children of the Garabedian family, a portrait of Anahid’s father, and another of Khachig’s uncle. The family was large, and the cousins later found each other in Europe, where many of them had settled down even before the Genocide. This was the case with Manoug Garabedian, who lived in Geneva and was engaged in the antiques trade. His son, Rodolphe, would later become an architect, and his daughter, Araxi, would open an art gallery. Another cousin, Mihran Garabedian (Kerovpe’s son), had settled down in Paris.

The young, long-haired girl in another photograph is probably Mannig, my grandfather’s sister. She died at a young age from tuberculosis, if I am not mistaken. Physically, she bore a resemblance to my aunt Sona, who always kept a photograph of her in a silver frame.

Anahid Chamlian and Khachig Garabedian reached Marseille in 1923. My aunt was born in this city. From Marseille, they left for Brussels, where they joined Garabed, Khachig’s brother (whom I never met); and Vartanoush, Khachig’s mother. The latter was a widow, who was later buried in Brussels Cemetery. She was a quiet woman, always dressed in black, and had been traumatized by the frequent and rapid changes in her surroundings and by her life in a county with an unpleasant climate and a foreign language. My mother, Hasmig (1930-2017), was very attached to her sensitive and uprooted grandmother. Khachig died of a heart attack in 1959, and Anahid died in 1992. They were buried in Brussels Cemetery, where they were later joined by Hasmig. There are also some Geyvetsis in the United States. Among them, I remember Gloria Missirian, who was a distant relation of my grandmother’s. There was also a cousin who lived in New Jersey, Harry Papazian, who was a descendant of Lazarus and Helina Papazian. Harry’s father, Nerses, had arrived in the United States in 1922. Helina was Hadji Ohan Chamlian’s sister.