Nany Tendjoukian collection - Burlingame, CA

Cities and People

Author: Maroush Yeramian, 15/06/21 (Last modified 15/06/21) - Translator: Hrant Gadarigian

Why do people take photos? In particular, why does an educated person take photos when they can immortalize the moment in writing?

It is said that human beings tend to remember the worst moments, but not the good ones, and therefore they want to capture the pleasant and sweet moments in photos. It’s as if they do not trust their memory or the ability to preserve images in their gaze.

Photos also show what is important for us during our lives. They are part of our heritage and can tell us, in complex language, what words often cannot.

Throughout Armenian history, Armenians, wherever they have lived, have often moved - individually, with their families or in groups. This has been the case of Armenians settling in Nor Jugha.

The most difficult of these journeys, of course, was the expulsion of 1915 and the dispersal of Armenians.

During such moves, people do not have the ability to carry even the bare minimum with them, and often remember with regret their abandoned estates, lands, and belongings.

But strangely, in an almost incomprehensible way, these things travel independently of their owners, only to end up, if not with their owners, then with people close to them, or with people who pay special care to those things.

The recipient or acquirer of such items also "acquires" a story in the process. That is, they hear it from the giver or the seller. Such stories make people enclined to trust their thoughts and memories, without reflecting that the brain often plays mind games and forgets things that are so important to us. But not to the mind, that retains an event to the extent that we frequently recall that event, because we sometimes recall the memory of the event in our mind and not the event itself. That is, the more we remember an event or a person, the more it is set in our minds, whereas we can forget an especially important event, if we do not evoke it often, despite its importance to us.

Of course, we can record something with a pencil on paper or via digital devices. But we are so far removed from writing that even writing/recording on a computer or cell phone never occurs to us.

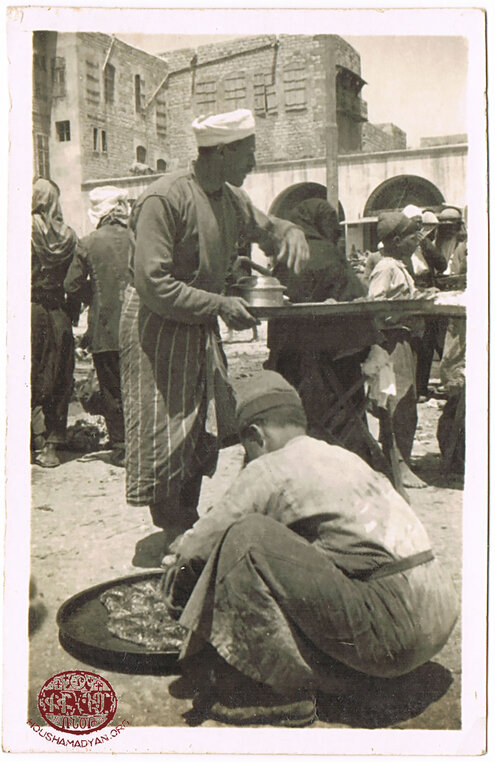

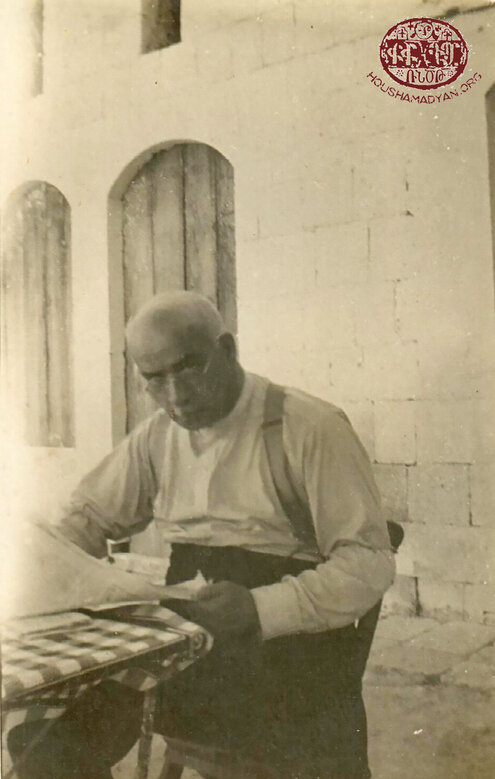

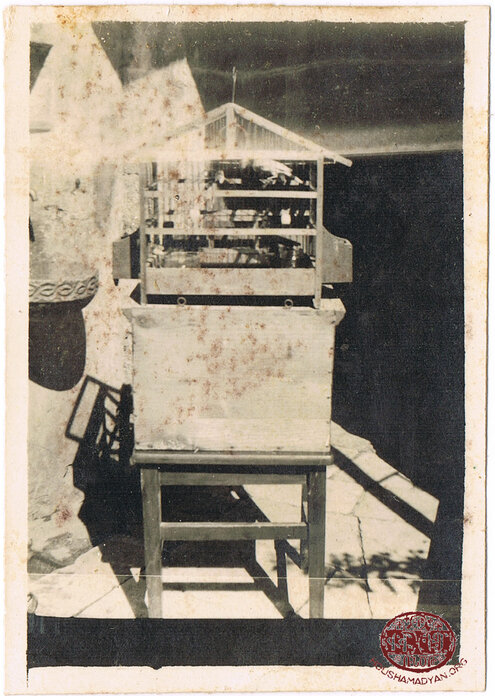

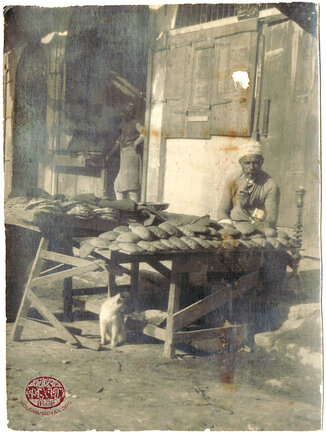

To this day, almond sellers in Aleppo, Cairo, and other Arab countries roast the almonds and then place them in such trays to cool.

The collection of photos included in the album presented on this page underwent such a journey. Here we look at authentic and very old photos, as if reliving their adventure, moving from place to place and from hand to hand, until they reach their final destination.

So now, it’s before my eyes. A decade ago, I might have said it was in my hands. But now it's much easier to have it in front of my eyes because of the ease of digitization. Before me, is a collection of incredibly old, and unfortunately neglected, photographs and images of photographs.

We use different expressions depending on where we come from. For example, the expression “let's take a picture" (badger mu arnenq) used by the Armenians of Istanbul has reached Cairo and Alexandria, while the Armenians of Syria and Lebanon would say "let's be photographed" (ngarvink) or decades ago, "let's pull a picture" (ngar mu kashvink).

Photographers, whether professional or ordinary people, generally carefully choose the moment, position, and clarity of a photograph in an effort to enhance the image.

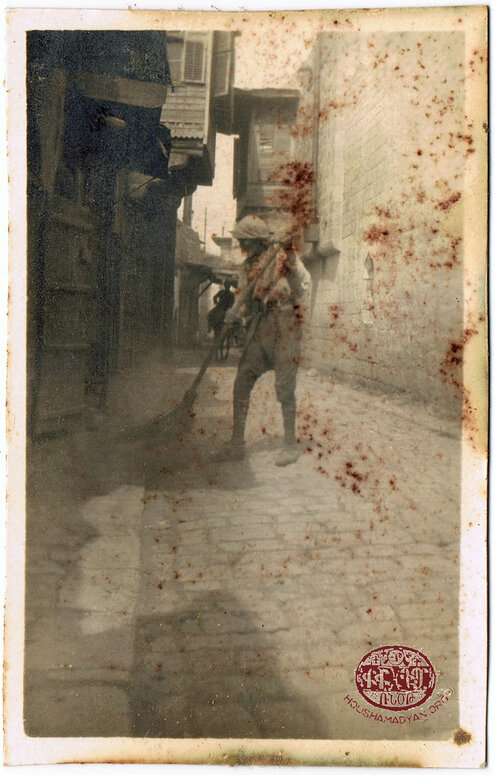

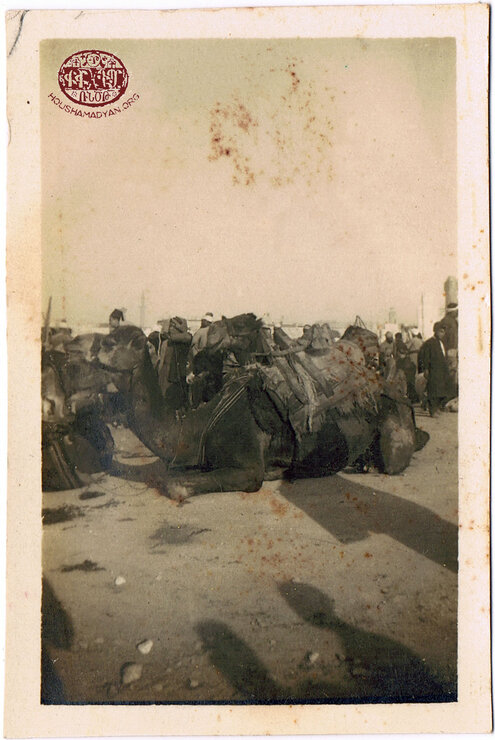

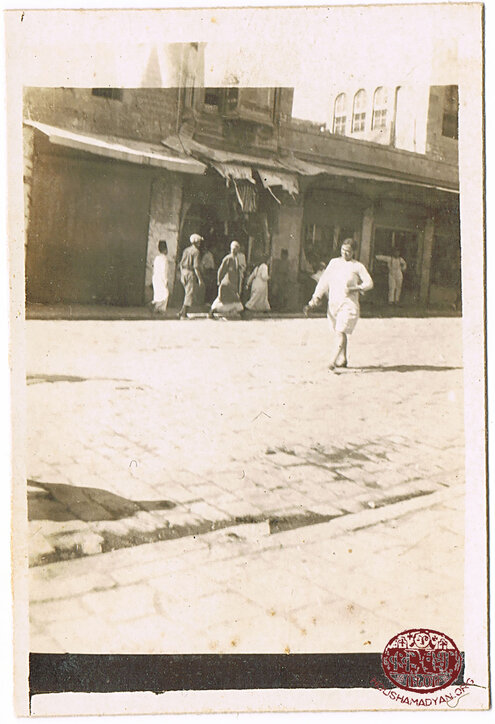

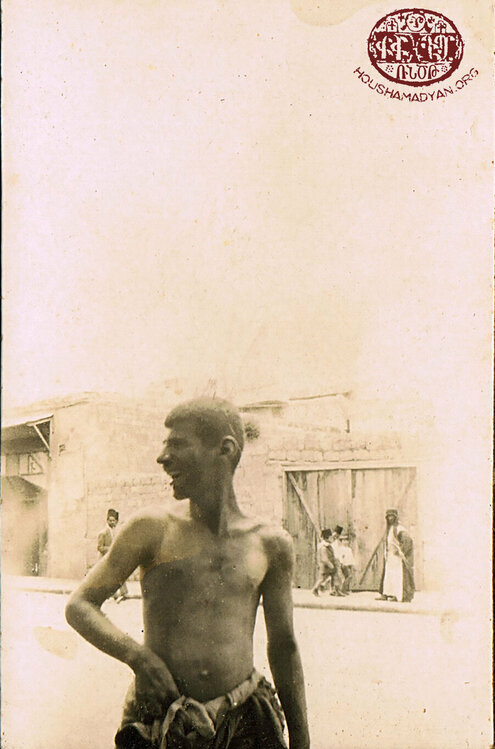

In this collection, however, there is no such effort. There is a rush, a need to not lose the moment or place and to record it immediately.

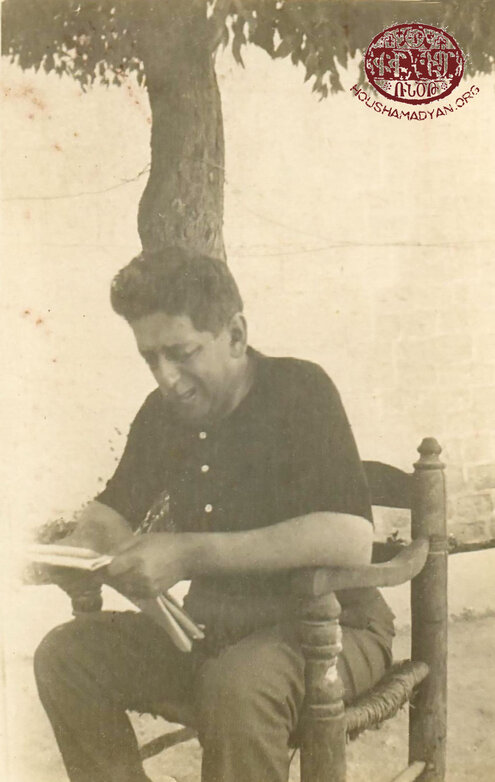

Portraits of two people can be seen in this collection - of Dr. Kh. Boghosian and Philip Arpiarian. Why only these two? Are they friends of the photographer or were they taken unexpectedly?

Each person photographs the same scene or event in his or her own way, bearing his or her own mark on the photograph.

Who is the author of the photos in this album and where is the photographer's stamp on the images?

It is said that the album belonged to two Istanbul-Armenian brothers, Stepan and Dr. Henry Arslanian, and they were left with their sister, Regina Arslanian-Torosian, and later passed to the daughter of her sister-in-law, Shakeh Torosian-Torosian, because Regina was childless, and later wound up in the hands of Shakeh’s daughter Azniv Torosian-Torosian. Finally, it passed to the daughter of Azniv, Nany Torosian-Tendjoukian.

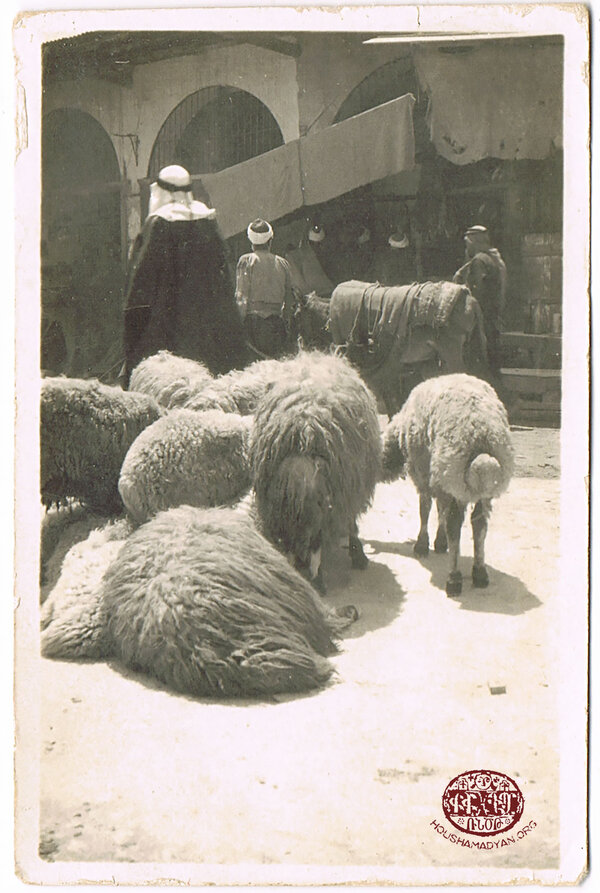

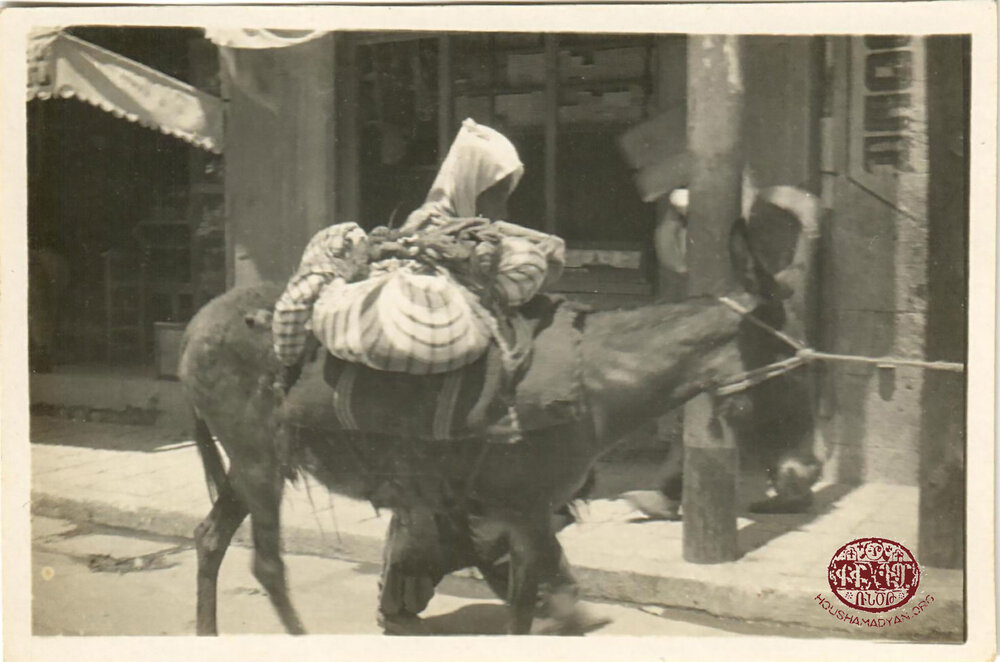

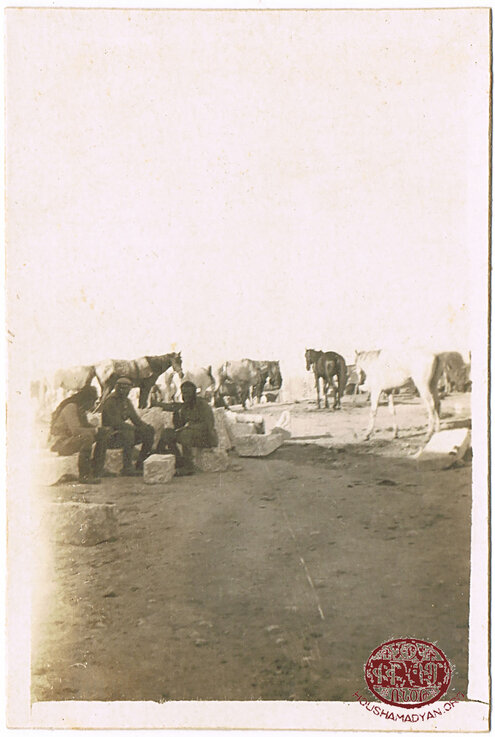

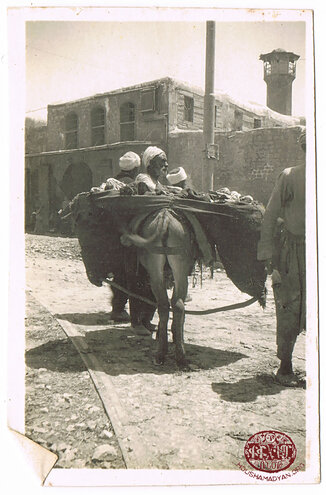

The name Vaghinag Pyurad is mentioned once in this entire saga. Under one of the photos, clearly written in his own hand is, "I myself". (Confirmation of the handwriting comes from V. Pyurad’s grandson, Haik Byurat, who lives in the USA. However, this is most likely a joke of Pyurad because what appears in the photo picture is a pack animal.

It՛s also said that the two Arslanian brothers were well-to-do and traveled a lot, as if to prove ownership of the photos.

But when we consider that Vaghinag Pyurad, judging by his biography, was not only quite a traveler, but also one of the survivors of the Titanic shipwreck, we are convinced that he also traveled quite a bit.

We read about this in the memoirs published by Vaghinag Pyurad, the foreword of which was written by Shahen Khachatryan, who, according to his story, was a close friend of Vaghinag Pyurad's son. The book can be accessed here: https://arar.sci.am/dlibra/publication/279330/edition/256230

Despite all this, we have a hard time defining the ownership of the album, which, however, is not as important as the existence of those photographed and the information stored within.

It is true that some album photos have inscriptions, but they only mention the name of the place where the photo was taken. They do not say anything about the photographer, the circumstances, or the date of the photo.

If we accept that the album belonged to Vaghinag Pyurad, then how did it end up with the Arslanian brothers? This is the main mystery. Were these three linked to one another, or did they spend time together in Aleppo and had the opportunity to take photos and be photographed?

There is still the photo of cats, under which is written "My Aleppo cats”. Which of these three, the Arslanian brothers and Vaghinag Pyurad, lived in Aleppo because they had to live somewhere to keep cats?

Apart from the question of ownership, however, when we look at the 46 pictures, they immediately group themselves into four sections.

- Portraits.

- Scenes.

- Villages, settlements and cities.

- Cats: "My Aleppo cats”.

In addition, there are many untitled pictures in these four groups apart from the first.

Whoever this album belongs to, its photos, especially the photo of people, remind us once again of the people who played an important, or some role, in the life of Western Armenians and then were forgotten. Preserving this album is a way to save them from oblivion.

Vaghinag Pyurad

Vaghinag Pyurad was the first child of Smpad Pyurad, a Western Armenian writer and one of the victims of the Armenian Genocide. The younger brother was Haig Pyurad.

Vaghinag Pyurad was born in Zeytun, in 1886. After receiving his primary education at the local school, he continued his studies in Alexandria and Cairo, where the family lived those days.

In 1903, Vaghinag enrolled at the Mekhitarist College in Venice, where he was taught excellent Western Armenian, but also Latin, Italian, and French, as well as editing and lithography.

Vaghinag Pyurad is one of the most important names in the publishing business of Constantinople and several Diaspora communities. He not only published almost all the books of his father, Smpad Pyurad, but also the works of writers from different places because he lived and worked in Rome, Paris and Marseilles.

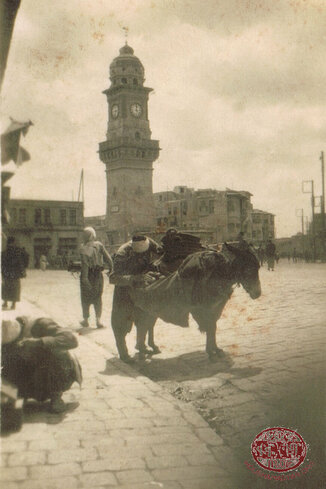

Construction took a year and was completed in 1899. The clock tower was demolished in 1904.

After fifty years of inactivity, the clock was refurbished with an English clock machine purchased from the same company as London’s Big Ben clock.

In 1907 he returned to Constantinople and founded the Modern Lithography publishing house. He did translations, published them, and distributed them outside Constantinople, in various countries. It was at this time that he was rescued from the wreckage of the Titanic on his way to America.

Fleeing Turkey during the Genocide, he lived in Syria, Lebanon and Egypt from 1925 to 1946.

He immigrated to Armenia in 1946 and died there in 1972, full of regret that he couldn’t carry out the latest wish of his father, received from Ayash (his place of exile) – “I’m already dead. Forget my body and save my writings.”

Numerous volumes published by Vaghinag Pyurad can be found today at the AGBU Yervant K. Aghaton Library in Egypt.

Dr. Khachik Boghossian

Khachik Boghossian, an equally famous figure, was born in 1875 in Germir (Caesarea/Kayseri region), where he received his primary education. He moved to Constantinople where he started to study at the Ottoman Medical University. He left the Ottoman capital, continued to study in Lausanne, graduated from the local medical university and specialized in psychiatry.

He returned to Constantinople and in 1906 was appointed head of the psychiatric ward at the National Hospital.

He served in the Ottoman army.

He settled in Aleppo in 1923, where he was active in public life and lived there until his death in 1955.

He was a member of psychiatric societies in Switzerland and Paris.

In 1913, he was elected Deputy Speaker of the Armenian National Assembly of Istanbul from Angora/Ankara and held this position until the end.

He was a member of the Ramkavar Azadakan Party, as well as the licensor of the Aleppo Yeprad daily (originally three days a week).

He was one of the main founders of the Verjine Gulbenkian Maternity Hospital in Aleppo.

Philip Arpiarian

Arpiar Arpiarian's nephew. His family is from Agn/Egin.

He was born in Constantinople, where he received his education and a certificate in geometry.

He had an innate talent for satire.

He settled in Egypt.

He was the civil engineer of the famous Al Kalima (Arabic for "Word") Hospital in Aleppo, which still operates today.

***

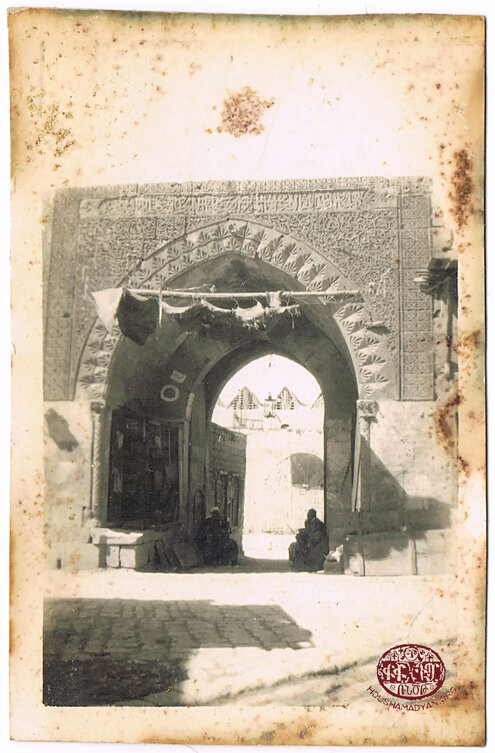

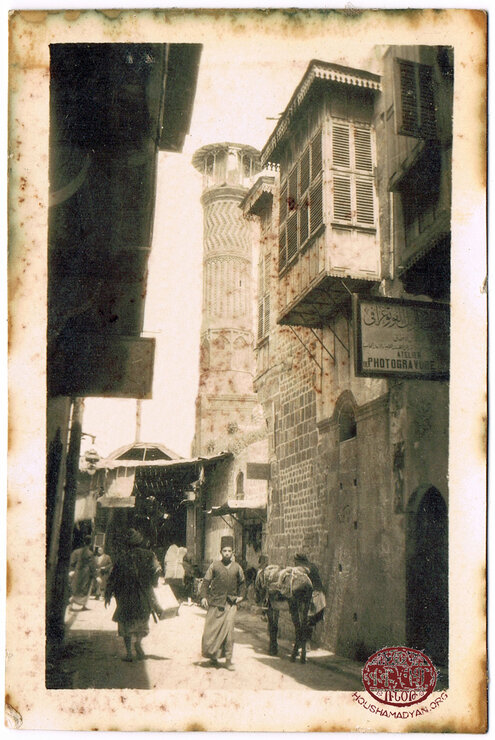

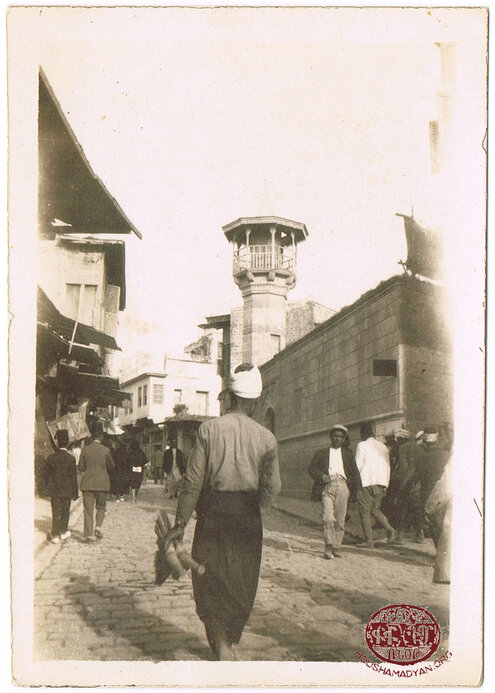

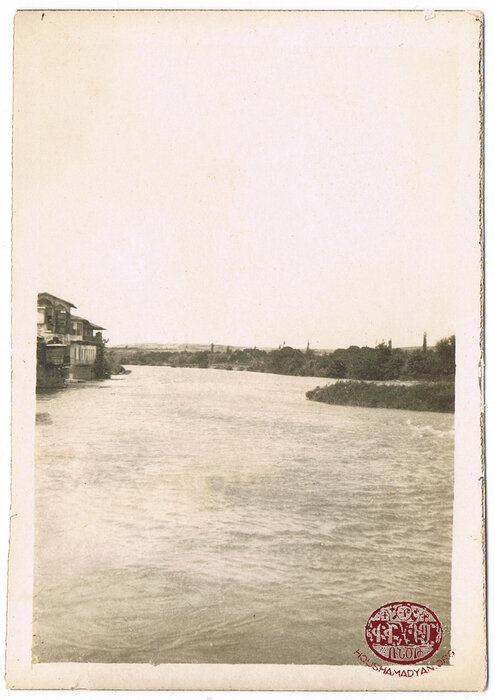

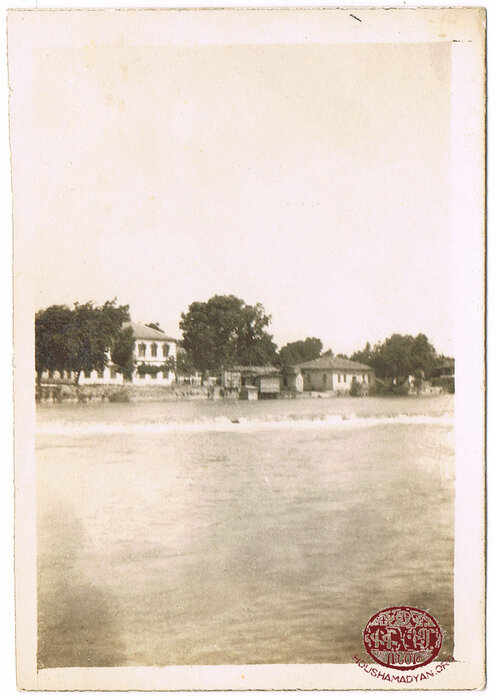

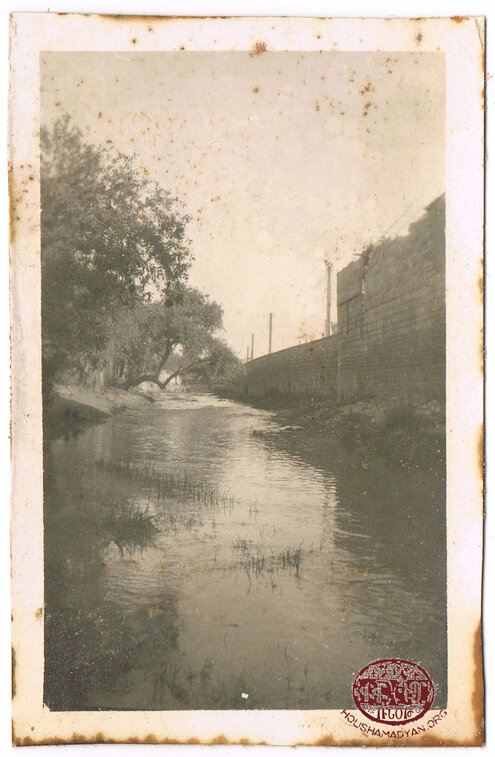

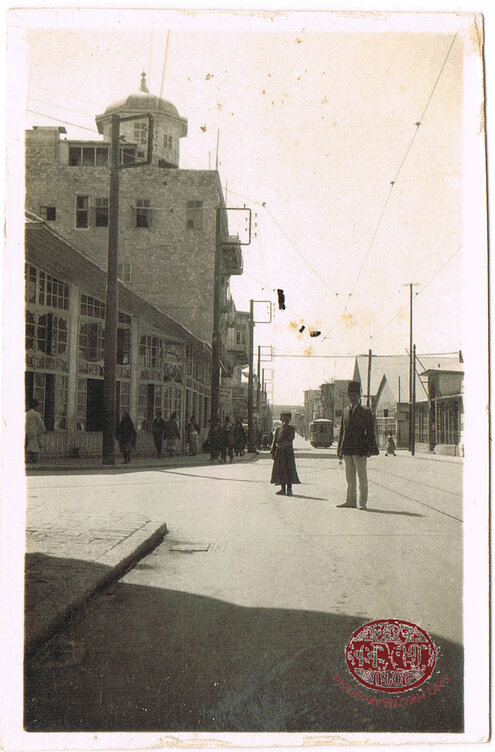

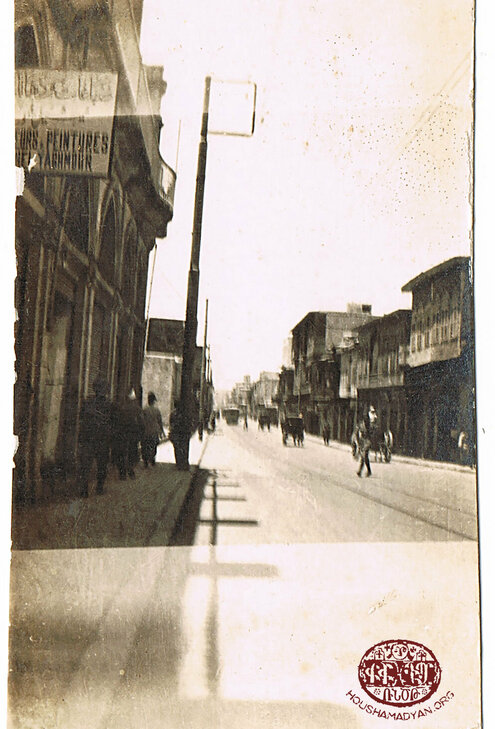

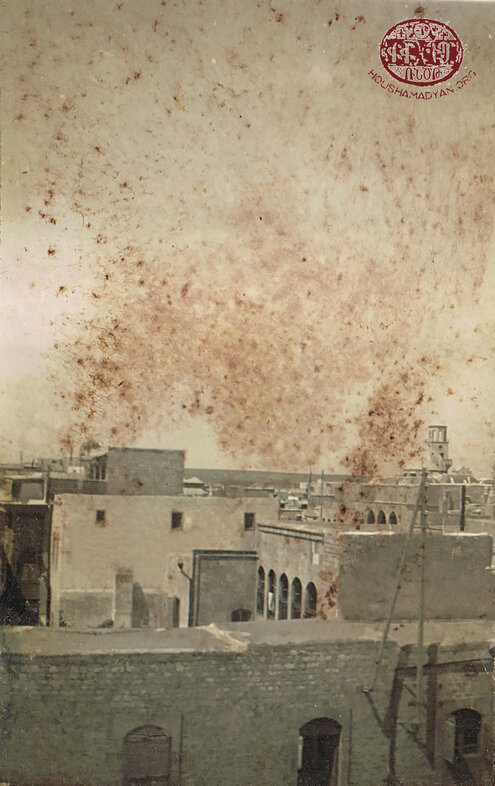

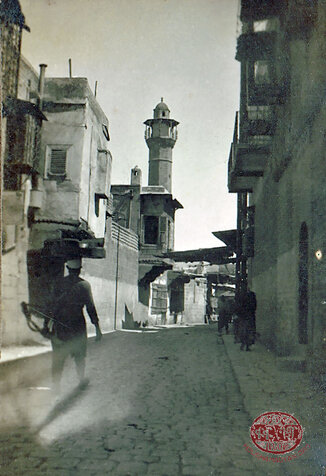

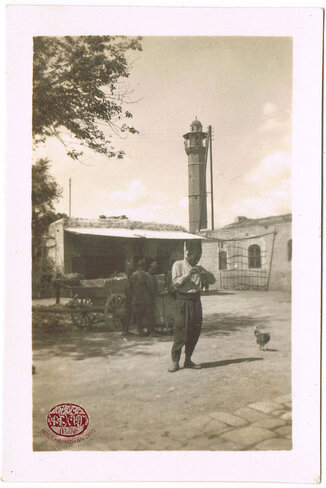

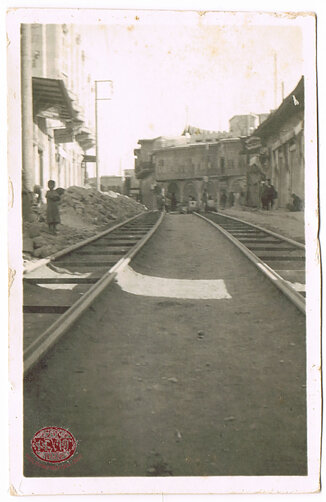

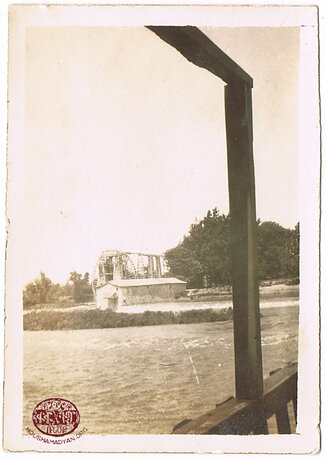

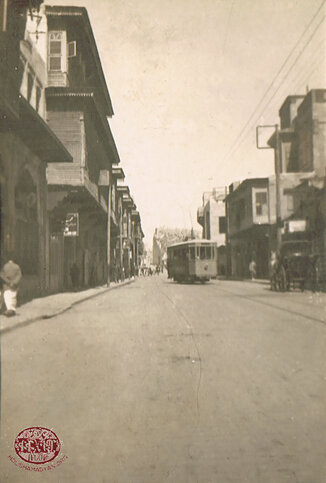

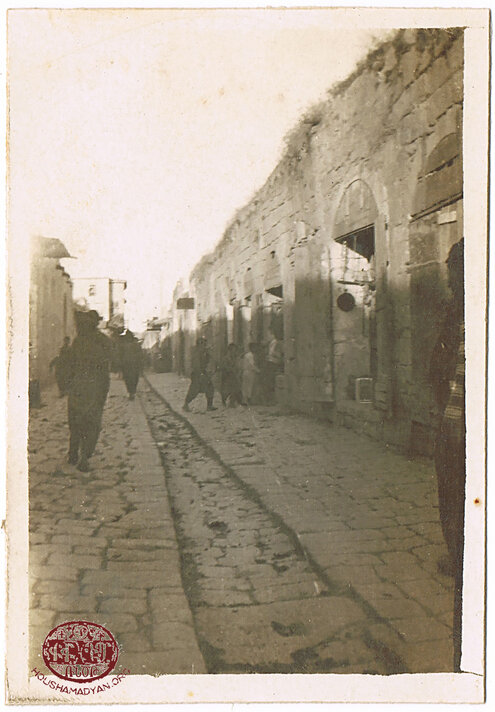

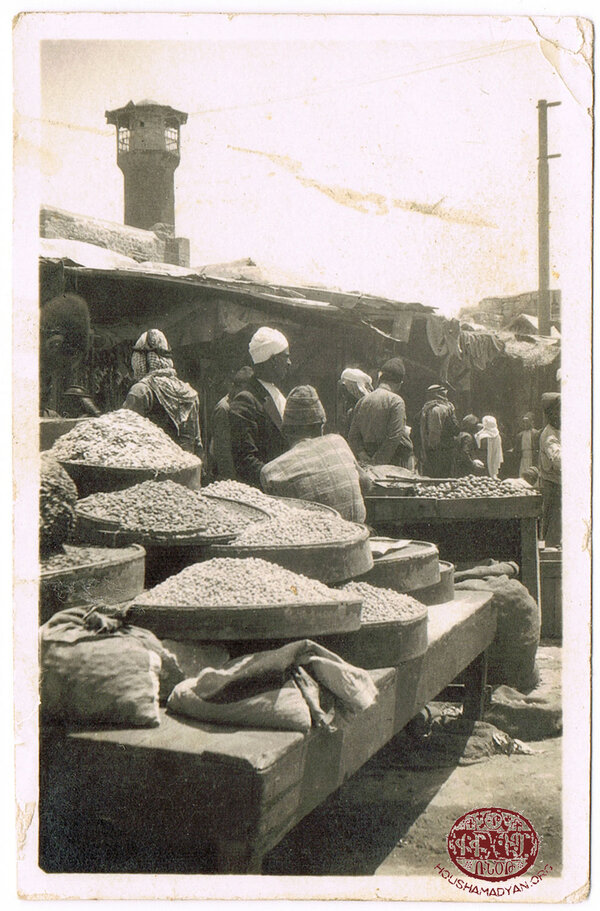

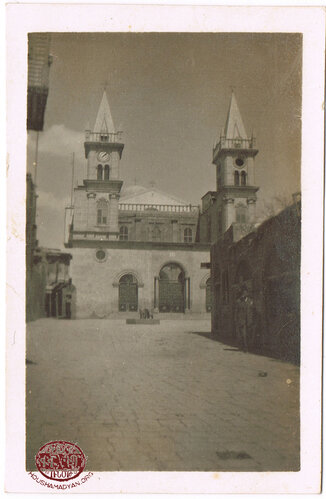

As for the photos of towns and villages, they give some idea of the condition of several villages, such as Teftenez (a Cherkez village), settlements, like Idlib, and the towns of Ayntab, Aleppo, and Constantinople at that time.

This type of bread is common in several Arab countries - Syria, Lebanon and Egypt. Removed from the oven, the bread is placed on long boards and, if it is to be delivered, the bearer balances all the weight on his head and cleverly maneuvers through the streets. This custom is still practiced in different cities, especially in the old quarters of Aleppo and Cairo.

During the last war in Syria, the church was bombed, and the dome was damaged. It was renovated in 2020.