Ashekian/Iynedjian/Bakalian/Bohdjelian Part III

Author: Anny Bakalian, New York, 18/11/2020 (Last modified 18/11/2020)

POST II: The Descendants of Harutiun Iynedjian of Kayseri/Gesaria

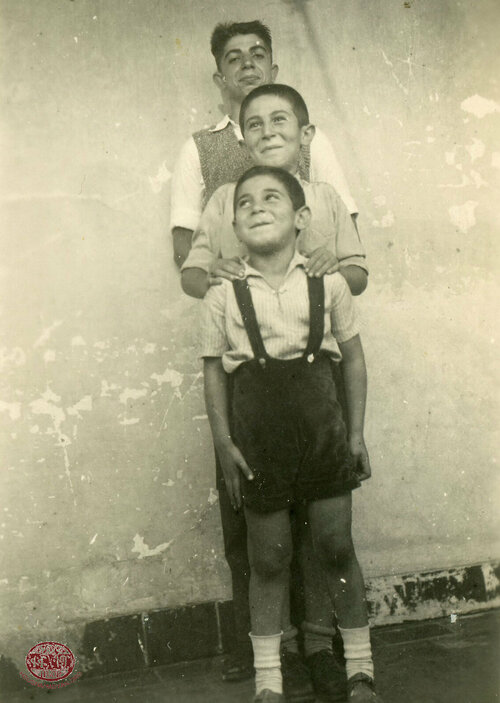

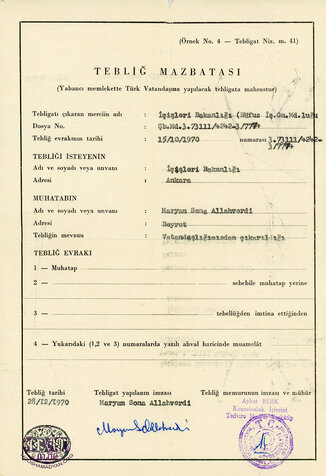

Haji Harutiun Iynedjian (born Kayseri/Gesaria—died in Constantinople), his son Bedros and family settled in Switzerland after 1915. Kevork Taniel Allahverdian was born in Banderma/Bandırma, after 1923 his name became Allahverdi. His daughter, Mariam Sona was born in Istanbul. Generally, women's lives are not memorialized, thus few of Sona’s friends are acknowledged.

In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne (24 July) acknowledged the “Republic of Turkey,” Ankara was proclaimed capital (29 October) and Mustafa Kemal became the first President. Radical reforms followed such as the centralization of education in 1924, banning headgear like the Fez and traditional dress in 1925, the introduction of the international time zone system, the introduction of the international-Gregorian calendar from January 1, 1927, and adoption of a new Turkish alphabet in 1928. Constantinople was changed to Istanbul in 1930. These reforms were glorious for the Turks, but hostile, even some laws were punitive, towards Armenians and other minorities. The Vatandaş Türkçe konuş! (Citizen speak Turkish!), in 1928 did not allow Armenians and Greeks to speak their native languages in public. The Surname Law of 1934 Turkified names, for example, Kevork Allahverdian’s name changed to Allahverdi; Partikian became Partikoğlu, Kalenderian became Kalenderoğlu. Further, geographical names (such town/village, street, lake, and mountain) that were Armenian, Assyrian, Greek and Kurdish were changed into Turkish.

The stories of the Ashekian Clan from Kayseri/Gesaria continue with Haji Harutiun Iynedjian, the in-laws, those who passed through Constantinople/Istanbul and the few who stayed. Circa 1895, Bedros Harutiun Iynedjian established his enterprise in the capital of the Ottoman Empire. A few years later, his sister, Dikranuhi (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Torosian, settled there when she got married. About 1910, their father, Harutiun Iynedjian of Kayseri/Gesaria moved to live with Dikranuhi. After the armistice, Nevrig (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Allahverdian and her family lived in Istanbul.

The Second Generation

Haji Harutiun Iynedjian (born in Kayseri circa 1825—died in Constantinople circa 1915) had a silk threads business and was the chief of the Armenian quarter in Kayseri/Gesaria.

Harutiun Iynedjian married Mariam the daughter of Bedros Uzun Ashekian, the son of the patriarch. This marriage—Iynedjian-Ashekian—created one of the branches of the Ashekian Clan of Kayseri that included also the Allahverdian/Allahverdi, Ayanian, Bakalian, Baltayan, Bohdjelian and others.

Harutiun and Mariam had four older daughters, followed by three sons:

- Gyuldudu (née Iynedjian) Bohdjelian (born in Kayseri circa 1860—died in Bucharest in 1957)

- Diruhi (née Iynedjian) Ashekian (born in Kayseri, circa 1864—died in Beirut on June 11, 1968)

- Dikranuhi (née Iynedjian) Torosian (born in Kayseri died circa 1866—died in Istanbul on December 26, 1946)

- Nevrig (née Iynedjian) Allahverdian (born in Kayseri circa 1868–died in Istanbul in 1967)

- Hovhannes Harutiun Iynedjian (born in Kayseri circa 1870—died in Romania circa 1940)

- Nazaret Harutiun Iynedjian (born in Kayseri circa 1872—died close to Aleppo during the Armenian Genocide)

- BedrosHarutiun Iynedjian (born in Kayseri in 1874—died in Lausanne in 1961)

When Mariam’s paternal uncle was infected by typhus, she went to his house to care for him. While he recuperated, unfortunately, she contracted the disease and died. Their youngest child, Bedros, was two years old when his mother passed. Harutiun raised his younger children until they matured; he found husbands for his daughters and he sent his sons to Kastemoni/Kastamonu to find their future.

Later in his life, Harutiun Iynedjian spent sojourns with each of his daughters on different parts of Anatolia. He covered these expenses through the rents of a house and a shop in Kayseri that he owned. The Clan’s historian, Garabed Ashekian, mentions that Harutiun Iynedjian was a kind and popular man. During World War I, he died at the age of 90 and was buried in Uskudar/Üsküdar (Constantinople).

The Third Generation

Gyuldudu (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Antreas Bohdjelian(born in Kayseri circa 1860--died in Bucharest in 1957)

Diruhi (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Parsegh Ashekian(born in Kayseri circa 1864—died in Beirut, June 11, 1968)

Dikranuhi (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Garabed Torosian (born in Kayseri circa 1866—died in Istanbul in 1946) settled in Constantinople when she married Garabed Torosian (born in Kayseri—died in Istanbul in 1932) in 1901. His bosses were the Alianakian family, wealthy Armenians who had many properties and buildings. Garabed’s job was to manage shops, workshops and domestic rentals and their maintenance.

Dikranuhi and Garabed had a son and a daughter:

- Mgrdich Torosian (born in Istanbul on March 1, 1905—died in France)

- Takuhi Torosian (born in Istanbul on March 27, 1911—died in Istanbul circa 1980)

Even after his retirement, Garabed Torosian continued to help the occupants as if he never left his job. Ashekian says in, The History of Uzun Ashekian Clan, Garabed Torosian was respected and kind person and Dikranuhi created a very congenial family and was happy and extremely satisfied by her life; though her son’s departure to France affected her. [1] Garabed died in 1932 and Dikranuhi in 1946. They were buried in the Baghlarbashi/Bağlarbaşı Armenian cemetery in Uskudar.

Nevrig (née Harutiun Iynedjian) Taniel Allahverdian (born in Kayseri circa 1868–died in Istanbul in 1967) was the last of the four sisters. She married Taniel Allahverdian, the Allahverdians were born in Kayseri, but he had moved to Banderma for more commercial opportunities. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, members of the Clan intermarried. Hampartsum Allahverdian, Taniel’s older brother, married Mannik Bohdjelian, the daughter of Gyuldudu (née Iynedjian) Bohdjelian. The difference between Nevrig and Mannik in age was about three years; the aunt and the niece became sisters-in-laws.

The two Allahverdian brothers, Hamartsum and Taniel, had a shop that molded fezzes. They also traded in sheepskins and other animals. They built houses in Banderma and they owned orchards. One of their purchases was a farm that gave them anxiety, long trials and financial loss. According to the chronicler of Ashekian Clan, the brothers were decent and devout men, loved by their community.

In 1896, Avedis Bohdjelian (Mannik’s brother) was the first to settle in Constanța, Romania. Hamartsum Allahverdian with his wife Mannik followed him.

Nevrig and Taniel had two daughters and two sons:

- Hripsimé(née Taniel Allahverdian) Karekin Ayanian (born in Banderma, circa 1883—died in Knoxville, TN, on January 12, 1984)

- Harutiun (Artin) Taniel Allahverdian (born in Banderma circa 1884—died in Yerevan, circa 1980)

- Nevart(née Taniel Allahverdian) Garabed Baltayan (born in Banderma circa 1889—died in Istanbul circa 1965)

- Kevork Taniel Allahverdian/after 1923 Allahverdi (born in Banderma in 1891--died in Istanbul on May 8, 1970)

In 1913, Taniel Allahverdian moved his family to Constanța (Romania) because he was anxious about a plausible war and his brother, Hampartsum, was already there. He left Banderma with his wife, Nevrig; their daughter Nevart who postponed her wedding that autumn; and their sons Harutiun (Artin) and Kevork. Soon after, their eldest daughter, Hripsimé Ayanian (born in Banderma, circa 1883—died in Knoxville, TN, on January 12, 1984), her husband Karekin (born in Banderma—died in Constanța in 1947) and their infant boy Garabed (born in Banderma in 1914—died in Philadelphia in 1991) followed them.

When the Ottoman Empire entered in World War I by their naval sortie against Russian ports in the Black Sea on 29 October 1914; Taniel’s family moved north to Odessa because it was safer; they stayed there until the end of the war. After the Armistice of 1918, all returned to the Ottoman Empire except their son Harutiun (Artin). However, another baby girl joined them--Hripsimé and Karekin’s daughter Hermine (born in Odessa in 1918).

The Allahverdian settled in Constantinople. Nevart’s wedding took place in 1919. Hripsimé and Karekin left their children with their grandmother, Nevrig, and traveled to Lausanne. They were exploring the possibility of Karekin finding a job in Switzerland. As nothing materialized, they returned to Constantinople, reunited with their children, and settled with them in Romania. Soon after, Taniel Allahverdian died; Kevork and his wife Kohar took good care of Nevrig at home in spite of the fact that she had lost her memory along with other complications of old age. She was lucky to witness the birth of her great-granddaughters, Ani and Sona Taniel Allahverdi, a well as her Bakalian great-grandchildren during their visits in Istanbul.

Hovhannes Harutiun Iynedjian(born in Kayseri circa 1872—died in Romania circa 1940) went to Kastamonu to establish his enterprise and was successful. The locals, both the businessmen and the authorities, respected Hovhannes. He started with selling fabrics; eventually his shop developed into a modern department store like the Orosdi-Back of Constantinople. [2] He would sell clothing and things for the home like china, glass, utensil in the kitchen, and carpets.

Hovhannesmarried Asanet (née Harutiun Suzmeyan) Iynedjian (born in Constantinople in circa 1887—died in Romania in 1940 circa), her father was a member of the Armenian court in Constantinople. [3] They had six children in order of birth:

- Harutiun Hovhannes Iynedjian (born in Kastamonu circa 1903—died in Constanța)

- Marie (née Hovhannes Iynedjian) Suzmeyan (born in Kastamonu circa 1904—died in Los Angeles)

- Vahram Hovhannes Iynedjian (born in Kastamonu circa 1906—died in Los Angeles in 1982)

- Haig Hovhannes Iynedjian (born in Kastamonu circa 1908—died in Bucharest)

- Ovsanna (née Hovhannes Iynedjian) Ashekian (born in Kastamonu in 1907—died in Los Angeles in 2002)

- Nubar Hovhannes Iynedjian (born in Kastamonu circa 1910—died in Bucharest)

During the Armenian Genocide, only the eldest son Harutiun was spared because he was in Constantinople. Hovhannes and his son, Vahram, were deported to Aleppo. Asanet was deported with Marie, Haig, Ovsanna and Nubar to a nearby village. After the 1918 Armistice, Hovhannes Iynedjian’s family eventually reunited in Constantinople as his father Haji Harutiun was already there.

During the Genocide, Hovhannes and his son Vahram were in Aleppo and survived. On their route to Constantinople, they went to Adana to visit his sister Diruhi (née Iynedjian) Ashekian. Hovhannes continued to do business in the capital. He would periodically go to Kastamonu to collect some of the money the Turks owed him. When Harutiun, Hovhannes’s eldest son, opened a store in Constanța (Romania), the family joined him.

Hovhannes and Asanet’s daughter, Marie, was betrothed before World War I to Haigazun Suzmeyan of Kastamonu. The bride and groom settled in Romania circa 1923 when Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) founded the Republic of Turkey (for Marie (née Iynedjian) Suzmeyan see POST III [forthcoming]). Her sister, Ovsanna married Hagop Parsegh Ashekian in Bucharest (for Ovsanna (née Iynedjian) Ashekian see POST III [forthcoming]). Like most of these marriages in the Clan, they were kin: Haigazun Suzmeyan was Asanet (née Suzmeyan) Iynedjian’s nephew and Hagop’s mother was Diruhi (née Iynedjian) Ashekian.

Hovhannes Iynedjian’s sons Harutiun, Haig and Nubar were not married. Harutiun died in Constanța and Haig and Nubar died in Bucharest; they were buried in Armenian Cemeteries. Their mother, Asanet (née Suzmeyan) Iynedjian was overwhelmed with grief; she was almost blind; eventually she died in Bucharest. Hovhannes, her husband also died in Romania.

Vahram Hovhannes Iynedjian survived his brothers; he owned a large grocery store in Bucharest with his brother-in-law Hagop Ashekian until World War II. To survive during the war, these men purchased a machine and produced stocks at home. In 1959, Vahram with his sister’s family left Romania. First, they went to Beirut to procure their visa to the United States, and in 1961 settled in Los Angeles (for Vahram Iynedjian and Hagop and Ovsanna (née Iynedjian) Ashekian see POST III [forthcoming]).

Nazaret Harutiun Iynedjian (born in Kayseri circa 1873—died near Aleppo during the Armenian Genocide) followed his brother to Kastamonu and worked with him selling fabrics. Then Nazaret purchased a farm in the town of Tashkopru/Taşköprü; it was several hours away from Kastamonu; he was not married. During the Armenian Genocide, he was deported. He arrived in Aleppo alive, but penniless. He sent a letter to his relatives, the Ashekians in Adana for help because he wanted to go to Nusaybin (near Mardin).

The Ashekians and Bakalians were exempt from deportation because their flourmill in Adana was producing flour for the army of the Ottoman Empire. Garabed Ashekian writes in his book that he sent the money to Aleppo; unfortunately, the money and his message were returned to him. The mail carrier had written on the envelope: “The addressee is gone to Al Khabour River.” During the Genocide, Al Khabour [4] meant he downed.

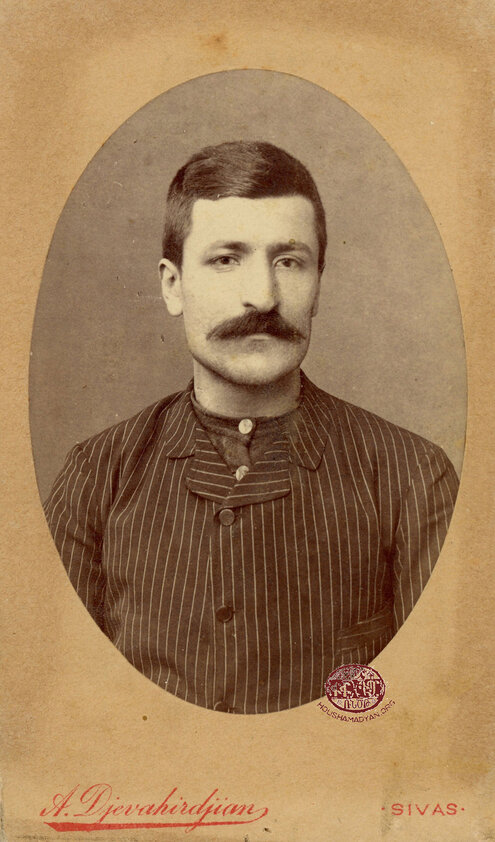

Bedros Harutiun Iynedjian (born Kayseri 1874—died in Lausanne 1961) was two years old when his mother died; his father took care of him and his sisters. Bedros was schooled in Kayseri; he spoke Turkish and wrote in Armeno-Turkish. [5] Bedros’s parents and his elder sisters Gyuldudu and Diruhi spoke only Turkish (and these women were illiterate).

While Bedros was a young man, he was apprenticed to his brother Hovhannes in Kastamonu to learn the skills of a merchant. After his tenure at his brother’s fabric store, he returned to Constantinople circa 1895 when he was 21 years old. There, he engaged in two profitable businesses; first he sold fabrics locally and then started sending goods to his brother’s establishment in Kastamonu. Later he also was one of the first Armenian businessmen to deal with copper. He shipped unaltered copper sheets to Banderma and Kayseri. Eventually, Bedros owned a sort of department store where customers would buy from household essentials to clothing.

In 1906, Bedros married in Constantinople Pérouze (née Hampartsum Suzmeyan) Iynedjian (born in Kastamonu on August 21, 1888—died in Lausanne in 1971), but her roots were from Kayseri. As confirmed in these families, the Kayseri Ashekians and Iynedjians married within their matrilineal and patrilineal lines. Bedros married the cousin of his sister-in-law, Asanet (née Harutiun Suzmeyan) Hovhannes Iynedjian. Also, Bedros’s niece Marie Hovhannes Iynedjian married Haigazun Hampartsum Suzmeyan, Pérouze’s brother. Asanet’s father, Harutiun Suzmeyan, was a lawyer and worked at the Ottoman Court.

Pérouze’s first schooling was in Kastamonu; when her family moved to Constantinople circa 1900, she attended Essayan School and later learned French at Notre Dame de Sion. She also spoke Turkish because it was the official language of the regime. She had eight siblings; she was one of the younger ones. [6]

Bedros and Pérouze lived in Kadikeuy/Kadıköy, a cosmopolitan district in the Asian side of Constantinople, facing the historic city center at the European side and the Bosporus.

The couple had a daughter and a son:

- Mariam Bedros Iynedjian, changed to Marie in Switzerland, (born in Constantinople, November 24, 1907— died in Lausanne 1953)

- AramBedros Iynedjian (born Constantinople, in October 14, 1910—died in Lausanne, August 1973)

In 1913, Pérouze started coughing, sneezing, had chest pains and felt fatigued. She went to her doctor, and he confirmed that she had Tuberculosis (TB). Tuberculosis, along with Syphilis and Malaria, were the most contagious diseases in the Ottoman Empire. The cure at that time was to keep the sick in a sanatorium. Surp Prgich Armenian Hospital in Constantinople had a TB sanatorium established at the end of the 19th century; however, Bedros decided to take his wife to Europe. The couple had two young children, the daughter was six years old and the boy three years old; he left them with his sisters, Nevrig (née Iynedjian) Allahverdian and Dikranuhi (née Iynedjian) Torosian. He also left his business to his nephew, Harutiun Hovhannes Iynedjian, and his trusted employees.

On their ship to Marseilles, Bedros met a traveler who suggested that Switzerland had the best doctors for treating TB and their sanatoria were at high altitudes. Bedros and Pérouze traveled by rail until they arrived at Leysin (in the canton of Vaud—district of Aigle). Dr. Auguste Rollier was famous for his treatments for TB at the Grand Hotel de Leysin, he was called, “Sun Doctor.” Bedros left his wife and returned to Constantinople. He made frequent visits to observe his wife’s improvement and corresponded with her by postcards in Armeno-Turkish. In early 1915, Pérouze was still at Grand Hotel de Leysin; while, Bedros, Maryam and Aram were in Lausanne. Bedros still corresponded with his wife by postcards.

In late 1914 or early 1915, the political and economic situation was grim. World War I was intensifying, and the Armenian Genocide started in 1915.

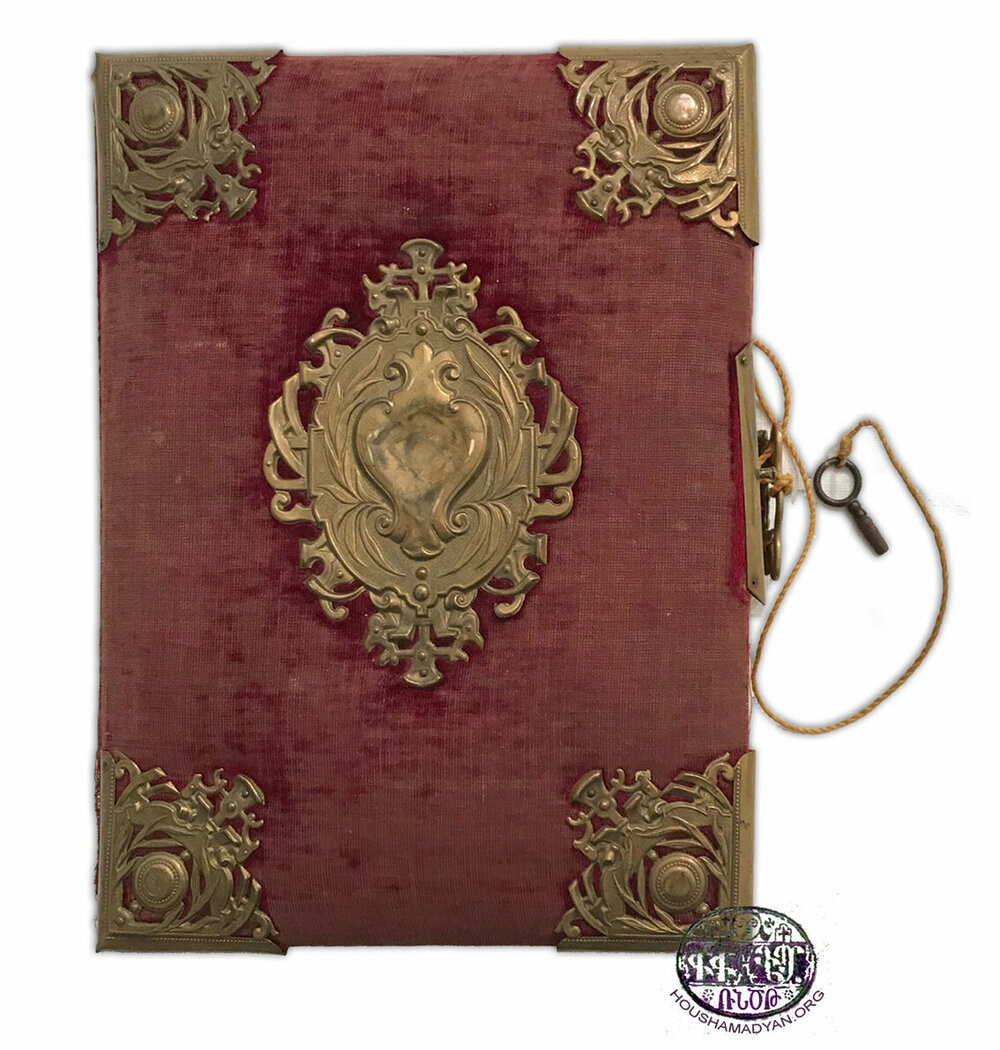

Eventually, the Iynedjians settled in a township called Chalet-à-Gobet, north of Lausanne, where they lived in a building called Clinique La Forêt. [7] The first year was difficult for the Iynedjians in Switzerland and they were almost bankrupt. As his finances were limited, his sisters’ sons sent him small monies from Adana and Constanța. [8] They also survived on Pérouze’s gold and precious stones that she had brought with her, mostly from her trousseau. Still World War I was ravaging and the family of four needed shelter, food and education for the children. Pastor Agènor Kraft [9] was one of their first friends in Lausanne; he liked Armenians and encouraged them to persevere. Further, Bedros’s father-in-law, Hampartsum Suzmeyan, sent him the house rugs from Constantinople. Bedros sold them on the streets of Lausanne.

Bedros went one more time to Constantinople, possibly after the Armistice of 1918. He salvaged whatever he could ship from his house’s possessions and business in the Ottoman Empire. The cargo was sent to the address of one of his neighbors in Chalet-à-Gobet. A year later, the post carrier delivered a huge package. Bedros and Pérouze must have been overjoyed that their Kadıköy’s home –their living and dining rooms, carpets, bedding, vases, and as well as Pérouze’s album, full of photos—were in Lausanne. They were also appreciative that now they had the means to feed their family and send their children to school. Bedros sold the furniture and the carpets on the streets of Lausanne. Then he opened a shop on rue Petit-Chêne (in Lausanne) while Pérouze kept the books of the family’s finances.

Bedros must have learned French quickly in Switzerland. The Iynedjians spoke Turkish in Switzerland; their daughter Marie and son Aram also spoke Turkish. By the 1920s, Bedros started to buy oriental rugs from Paris and London, especially at the warehouse for carpet-exchange in London; it was located on the Circle Line Underground. [10] Bedros found an Armenian buyer in Turkey and another buyer in Iraq because he knew their culture and language. In 1922, he needed more space, so he moved his shop to Grant Pont. Pierre Iynedjian in his book mentions that his grandfather was a brilliant trader:

He knew how to operate a business, he knew how to sell and knew how to make a profit. Quite often he would spread the carpets out on the street to attention customers and when they came inside he would serve them tea and he would show off his carpets with a flourish by spreading them at the feet of his prospects. And if one carpet wasn’t what they wanted he would show them another and another. [11]

Armenians from Kayseri have the reputation of being stingy, but in reality, they were thrifty. Bedros taught his children and grandchildren that he “prospered by being both careful and generous with his money.” [12]

Bedros and Pérouze’s daughter Marie Iynedjian (died 1953) was a musician. Their son Aram Iynedjian had received his Swiss Maturité [13] from the Villa St-Jean in Fribourg, but throughout his childhood he learned business from his father, helping in his shop, as well as cleaning and repairing carpets.

Aram joined the carpet business in 1928; he opened shops in Geneva, Basle, Berne and a second store in Lausanne to tend to their customers better. Then Aram heard that a building was for sale; it had six floors the ground level had shops; below there was space for parking cars. In 1937, they bought “7 rue de Bourg,” in the center of Lausanne. The name IYNEDJIAN is still on the building. After World War II, they sold the shops except the original in Lausanne and Berne.

Bedros’s eldest grandson, Pierre, apprenticed in the family’s carpet shop, and for a year in 1960, three generations of Iynedjians worked in the same shop before Bedros died in 1961.

When the Iynedjian family settled in Switzerland during World War I, the laws did not allow immigrants to naturalize. Bedros, Pérouze, Mariam/Marie and Aram had “PASSPORT POUR ÉTRANGERS/Le titutaire du passport ne possède pas la nationalité suisse” [Passport for Foreigners/The titular of the passport does not have Swiss nationality]. However, after World War II, the law changed for those who had married a Swiss; as Aram had married Georgette Abrezol, a Swiss, he became a Swiss citizen in 1950. However, his parents and Marie were never naturalized.

Being part of the Kayseri Ashekian Clan, Bedros and Pérouze corresponded with their relatives and they hosted them in Lausanne.

One of the visitors was Hripsimé (née Taniel Allahverdian) Ayanian and her husband Karekin; she was the daughter of Bedros’s sister Nevrig. The couple had left their children with their grandmother: Garabed (born Banderma in 1914) and Hermine (born in Odessa 1918). As they stayed in Lausanne, they explored their opportunities for their future. However, they returned back to Constantinople, reunited with their children and settled in Constanța, Romania.

Another sojourner was Haigazun Suzmeyan; he was Pérouze’s cousin. He came with his younger brother Levon Suzmeyan who needed medical treatment. While waiting for his brother’s health to improve, Haigazun opened a rug store. The business went well, however, Levon died in Switzerland.

After Bedros’s death, Pérouze Iynedjian traveled to Beirut to visit her relatives. She stayed at the famous Saint George Hotel on the Mediterranean. For few weeks, Sona Bakalian and Lisbeth Bakalian entertained her. In summer 1965, Sona Bakalian and her daughter were guests of Pérouze Iynedjian at Gstaad Palace Hotel for a weekend.

The Fourth Generation

Descendants of Dikranuhi (née Iynedjian) Torosian

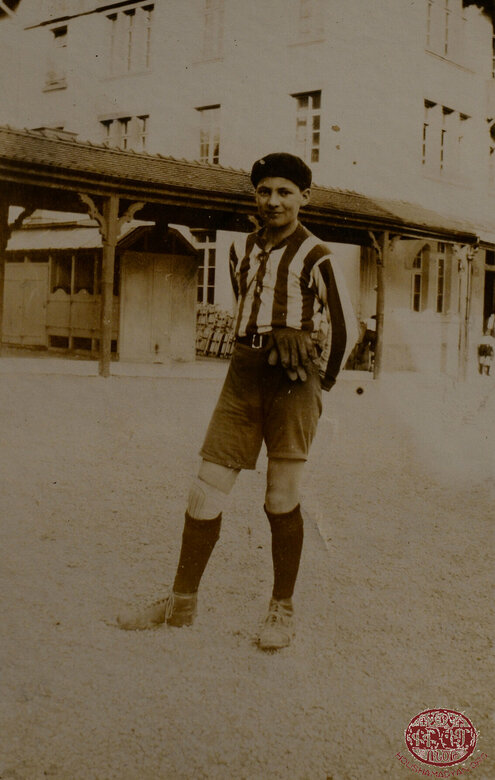

Mgrdich Garabed Torosian (born in Constantinople on March 14, 1905—died in France) attended the quarter’s Nersessian-Yermonian Armenian School for boys and girls and worked briefly for his cousin, Kevork Allahverdian/Allahverdi. When Mustafa Kemal Atatürk founded the Republic of Turkey and became the President in 1923, Mgrdich immigrated to France like many young Armenian men.

Mgrdich settled in a town some 80 km from Paris; there he bought a house and a shoemaker’s shop and he married a French woman. He missed his sister and wanted to visit Istanbul, but he suffered of rheumatoid arthritis and was in pain.

Since Mgrdich had no children, Mgrdich left his properties to the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU); every year the AGBU requests a requiem in his memory at the Armenian Apostolic Cathedral in Paris (15 Rue Jean-Goujon, at 8th arrondissement; built in 1904).

Takuhi Garabed Torosian (born in Istanbul on March 27, 1911—died in Istanbul circa 1980) attended the preliminary Nersessian-Yermonian Armenian School for boys and girls; she graduated from the Lycée Notre Dame de Sion (a famous school established by French nuns in Constantinople in 1856). She inherited from her parents a small house, then sold it and bought a more comfortable home in Uskudar and she supported herself with private French lessons.

The Fourth Generation

Descendants of Nevrig (née Iynedjian) Taniel Allahverdian

Hripsimé(née Allahverdian) Ayanian(born in Banderma, circa 1883—died in Knoxville, TN, on January 12, 1984)

Harutiun (Artin) Taniel Allahverdian (born in Banderma circa 1884—died in Yerevan, circa 1975)

Nevart(née Allahverdian) Baltayan (born in Banderma circa 1889—died in Istanbul circa 1965) was educated in Armenian schools. In 1913, she visited her maternal aunt, Diruhi (née Iynedjian) Ashekian. It was in Mersin that she was engaged to Garabed M. Baltayan of Kayseri. He was a manager at the Ottoman Bank. The couple was planning to get married in the autumn; however, the Allahverdian family fled to Romania just before the Ottoman Empire entered World War I. They returned to Constantinople after the Armistice (1918). Garabed Baltayan came from Konia to join his fiancée Nevart.

Nevart and Garabed Baltayan were married in 1919 and lived the rest of their lives in Istanbul. Garabed Baltayan first worked at the Deutsche Orient Bank, and then he worked for his brother-in-law Kevork Allahverdi.

The couple had a son:

- Ara Garabed Baltayan (born in Istanbul, September 6, 1920—died in New Haven, CT, August 7, 2015)

After his studies in Istanbul, Ara immigrated to the United States in the late 1940s. He worked as an engineer and had a family in New Haven, Connecticut and never returned to Turkey.

Garabed Baltayan suffered of rheumatism and later stomach ulcers. He died while the surgeon was operating on him in the early 1960s. Nevart was already a delicate woman; the fact that her only son and his family had not visited her exasperated her melancholy and feeling of isolation. She died few years after her husband.

Kevork Taniel Allahverdian/Allahverdiafter 1923(born in Banderma in 1891—died in Istanbul on May 8, 1970) was sent to his maternal uncle, Hovhannes Harutiun Iynedjian in Kastamonu to learn the skills of a businessman before World War I.

Taniel and Nevrig Allahverdian and his family relocated to Constanța (Romania) because of pending war. When the Ottoman Empire entered in World War I in October 1914, his family went north to Odessa because it was safer. Kevork Allahverdian peddled to support his family; he also bought merchandises to sell them in the Crimean Peninsula. He found it profitable until 1920, in the process, he learned Russian.

In his book, Garabed Ashekian mentions that Kevork Allahverdian escaped from the invasion of Dobruja by the Turkish-Bulgarian forces, and he joined his parents in Odessa. [14]

After the Armistice in 1918, Kevork returned to Constantinople and found a home for his parents and opened a grocery shop in Tophane, and then he moved to Kumkapi Balik Pazari/Fish Market. By 1958, he had changed his address Unkapanı, Yanuz Sinan Cami/Mosque Sokak/Street, Number 4 close to the Haydar Paşa Çeşmesi/Fountain (now called Fatih).

When Atatürk changed many laws starting in 1923, Kevork Allahverdian became Allahverdi. After these changes, Kevork Allahverdi was not able to claim his father’s properties in Kastamonu in spite that he was a citizen of the Republic of Turkey.

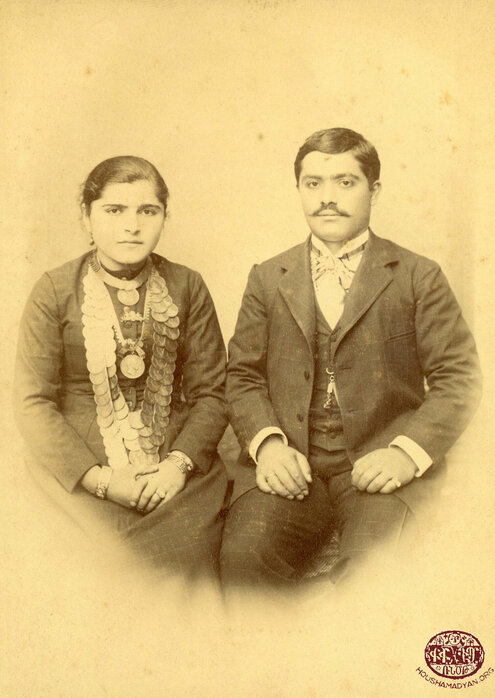

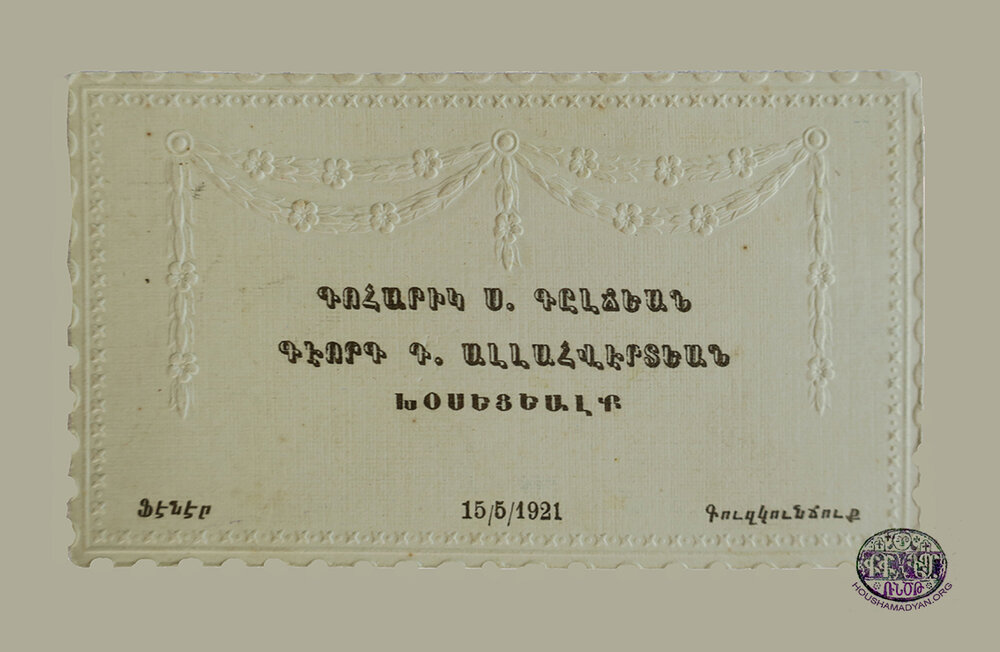

Kohar (née Keldjian) Allahverdian/Allahverdi (born in Constantinople in 1893—died Istanbul on July 8, 1997) married Kevork Allahverdian in 1921.

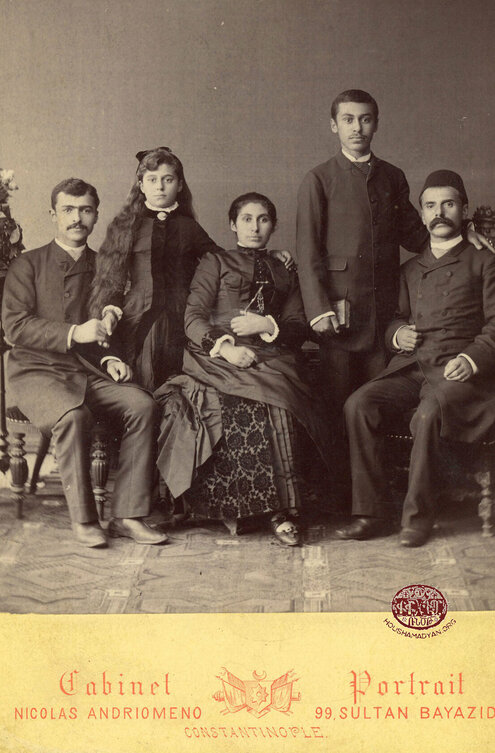

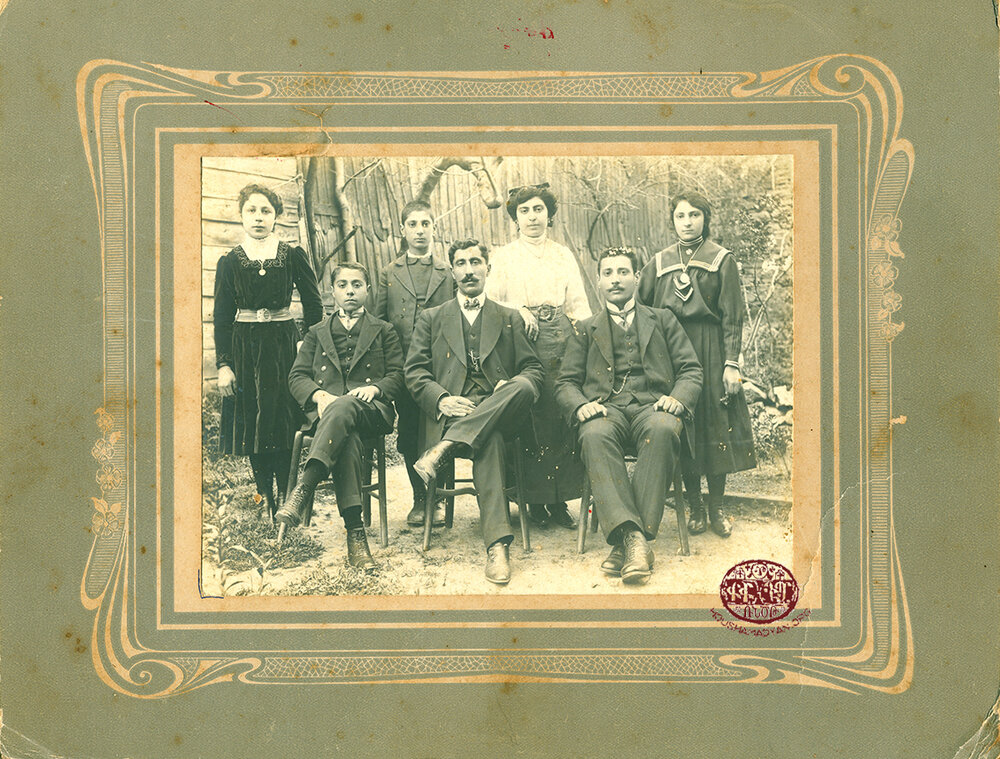

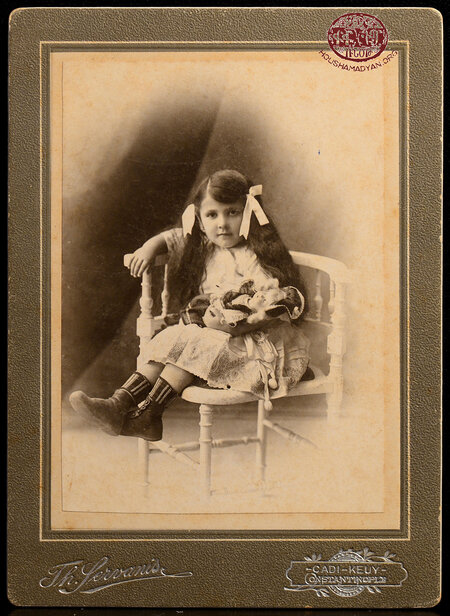

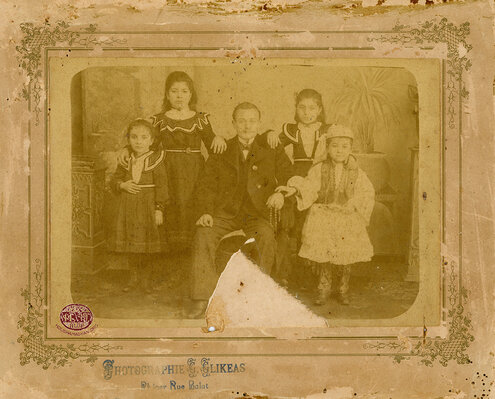

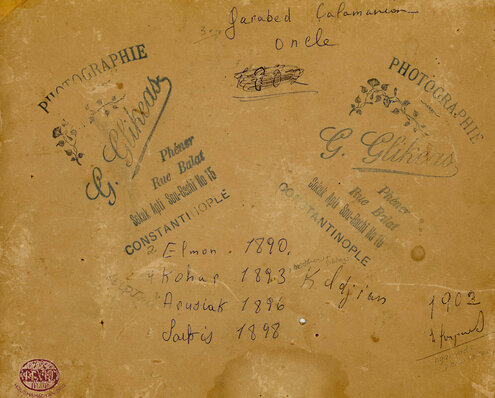

The Keldjian were from Kayseri, they were three sisters and a brother. In 1902, Garabed Calamanian [15] took his nieces and nephew to Photographie G. Glikeas, Phener [(Fener) Sokak Apti Sou-Bachu No. 15]. Calamanian was the children’s matrilineal uncle.

- Elmon(néeKeldjian) Tombulian (born in Constantinople in 1890—died circa 1930) married in 1919 and moved to Varna, Bulgaria, did not have children. She was visiting her family in Istanbul; took a ship back and she was never seen again. Her family thinks that someone killed her.

- Kohar (née Keldjian) Allahverdian/Allahverdi

- ArousiagKeldjian (born in Constantinople, in 1896—died in Istanbul in 1970)

- SarkisKeldjian (born in Constantinople in 1898—died in Istanbul)

The Keldjian children attended Armenian schools and even learned some French; understandably, they also spoke Turkish fluently and read and wrote Ottoman Turkish. During the Genocide, Kohar and Arousiag volunteered at the Kalfayan Orphanage in Hasköy (on the Golden Horn across from Fener). They washed the children, removed lice, cut their nails and/or hair, fed them, and cared for them.

Kevork and Kohar had one daughter and two sons.

- Sona Mariam (née Allahverdi) Bakalian (born in Istanbul, May 25, 1922–died in New York, March 27, 2006)

- Taniel Kevork Allahverdi (born in Istanbul in 1925–died in Istanbul 2007)

- Sahag Kevork Allahverdi (born in Istanbul 1933–died in Istanbul 2017)

When Sona was a child, her maternal grandmother lived in a house with a garden and trees in Fener (on the Golden Horn), along with her grandmother’s sister, her aunt Arousiag, and uncle Sarkis Keldjian and his dog.

After Kevork and Kohar married, they lived in a house with a garden on 7 Kadife Sokak (street) in Kadıköy, on the Asian side. In the 1930s, the Allahverdi family moved to Kurtuluş [16], near Feriköy Pasajı/passage. It is a neighborhood where many Greek, Armenian and Jews lived. Their address was: Kurtuluş Bozkurd Cadde/Avenue, Osman Bay, Apartment 21/6. Their building [17] was made of wood; in their apartment they had a heater stove in the living room, necessary in the winters. The room itself was pretty, decorated with green ceramic tiles of the heater [çini sobası in Turkish]. Their daughter Sona played the piano in that room under gilt framed tapestry of a mariner hanging on the wall; Kevork had brought it from Russia after World War I. Their home had running water in the kitchen and toilet, but the family members had to go to the Hamam weekly to bathe. Women and children had certain days and times and for the men it was a different schedule. Their building was torn down in the 1960s to open up an avenue.

Kohar Allahverdi raised her daughter Sona and two sons, Taniel and Sahag. As Kevork’s mother, Nevrig, lived with the family, Kohar nursed her until her death in 1967. Further, Kohar raised her granddaughter Ani, the first child of Taniel and Sophia. She was a petite woman, always active throughout her life, hardworking and engaged in her entourage and the world. Kohar was social; she received her friends and relatives one day per month. She prepared tea/coffee, sweets; and in case they stayed for lunch, it was always ready. Her regulars kept their slippers at the Allahverdi door. The etiquette was that all visitors should remove their muddy and dusty shoes before entering a home.

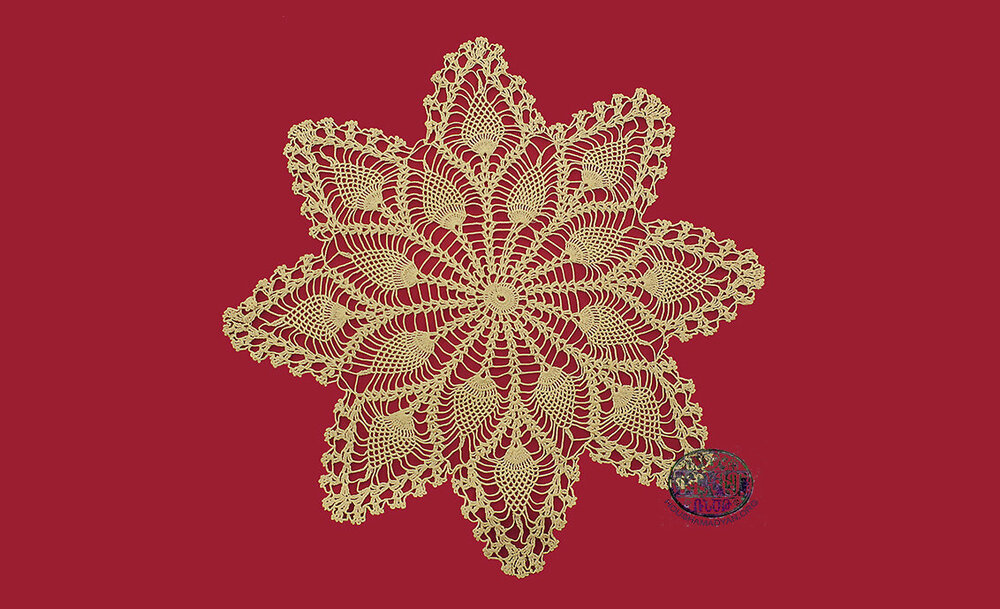

After her husband’s passing, Kohar visited her daughter Sona Bakalian in Beirut more often. Her suitcase was full of Kaymak (thick buffalo clotted cream, rolled and cut, eaten with honey), Midye Dolma (stuffed muscles), Kaltan (turbot), Lokum (turkish delight) from Ali Muhiddin Haci Beker’s shop close to Galata Bridge and her liquor, vişne (sour cherry). Kohar liked to be busy, she would make Pouf Boreg and Wheat Flour Halva for her grandchildren; she would knit and crochet, read Armenian papers, French magazines, and could understand some Arabic because she learned the Ottoman language in school.

Kohar was in Lebanon when the Civil War started in 1975. Kohar’s son-in-law, Pakrat Bakalian died in April 1976, in the mountain town of Baabdat. It was decided that Kohar should return to Istanbul because the situation was precarious. Her granddaughter, Anny Bakalian, was to accompany her to Damascus and then to Istanbul. Her grandson Sarko Bakalian and a couple of friends, in two cars, escorted them to Damascus, via the only route along the Lebanon Mountain range, zigzagging from one village and town until they reached Hrajel and slept there that night. The next day, they had to be in Faraya at 5 a.m., hundreds of cars, mostly Christian Lebanese, were waiting to evacuate. A convoy started about noon; a tank led the way with another tank at the rear. Many military jeeps were monitoring the exodus. It took over two hours to arrive to the Beqaa. Along the way, adults from villages watched and the children cursed, yelled, and threw stones at the cars. Kohar and her grandchildren were hungry, no one had eaten since breakfast; they stopped in Chtoura for their famous Labneh sandwiches, before continuing to Damascus, arriving the next day at 2 a.m. The Syrian Capital was full of thousands of Lebanese attempting to flee the war—hotel rooms were limited, as were airplane seats and there were long queues to get visas in consulates, as well as other necessary services. Kohar had lived all her life in Constantinople/Istanbul; however, had not witnessed war and Genocide. At the age of 83, she experienced that audacious journey back to Istanbul without any complaints. Kohar did not return to Beirut again until in the 1980s.

Kohar continued to occupy herself with watching television, cooking and crochet. As an active woman, she faced a difficult situation when her sight and hearing were diminishing in the 1990s, filling her with a sense of ennui. Kohar died at the age of 104 in Istanbul and was buried in the Shishli Armenian Apostolic Cemetery next to her husband and sister Arousiag.

The Fourth Generation

Descendants of Bedros and Pérouze Iynedjian

Mariam/Marie Bedros Iynedjian (born in Constantinople, in November 24, 1907—died in Lausanne in 1953) must have been eight years old when she arrived in Lausanne. She changed her name Mariam to Marie in Switzerland. She did not have the opportunity to become a Swiss citizen, as the laws changed after her death. She was an Ottoman Empire/Turkish Republic national and had to renew her residency often.

Marie attended the Conservatoire de Lausanne and became a concert pianist. She was not married. She died of Leukemia.

Aram Bedros Iynedjian (born in Constantinople in 1910—died in Lausanne in August 1973) lived with his family in Kadikeuy, in the Asian side of Constantinople. Their home included his mother, Pérouze (née Hampartsum Suzmeyan) Iynedjian (born Kastamonu on August 21, 1888—died in Lausanne in 1971), his father, Bedros Harutiun Iynedjian (born in Kayseri 1874—died in Lausanne in 1961) and his sister Mariam who was three years older than him. Their father was a successful businessman.

In 1913, his mother was sick, and the doctors said it was Tuberculosis. Bedros Iynedjian left his children with his sisters, Dikranuhi and Nevrig, took his wife to Switzerland. Within few years, Pérouze had gained her health and their father went to Constantinople and brought their children, Mariam and Aram, to Lausanne circa 1915.

Aram Iynedjian learned French very quickly and later German. He completed his Swiss Maturité from the Villa St-Jean in Fribourg. While the Iynedjians were Armenian, they communicated at home in Turkish.

Throughout his childhood and youth, Aram learned from his father how to run a business as well as the world of oriental carpets. Aram joined his father in the business in 1928 when he turned 18 years old, and then in 1937 he bought a building at 7 rue de Bourg, Lausanne. The son and father in the rug shop would use Turkish if a carpet buyer hesitated or such. Also, Aram used his Turkish with his colleagues if they were Armenian or Middle Eastern in Europe and when he travelled to shop in Istanbul.

Aram married Georgette Abrezol (born in 1915—died in January 22, 2010). Georgette had attended University of Geneva and completed her degree in dentistry; she loved sports and passed that to her children—climbing mountains and skiing in Switzerland, swimming in France and eventually Aram bought a house in Saint Tropez so his family would enjoy the summer on the Mediterranean Sea. They lived in Lausanne, later buying a big house on Avenue de Rumine, which is still in the hands of the family.

The couple had four children:

- Pierre Iynedjian (born in Lausanne in 1940)

- Patrick Iynedjian ((born in Lausanne in 1943)

- Annemarie Iynedjian (born in Lausanne in November 1945—died in Lausanne in May 2019)

- Christian Iynedjian (born in Lausanne in 1948—died in Saint-Tropez in 1971 of a car accident before his sister’s wedding)

Aram was the man of his era, he liked cars, bought a Pic-Pic (for Piccard and Pictet) manufactured in Geneva in 1937. He practiced tennis and skiing and his license to fly was in 1936. Aram and his wife, Georgette, began to collect paintings that were considered avant-garde like Jean Arp, Andy Warhol, Ellsworth Kelly, René Magritte and others. Also, Aram felt Armenian to invite Krikor Bedikian (born in Adana, in 1908–died in Paris, in 1981) to exhibit his paintings circa 1945; in return, Bedikian painted an oil portrait of his father. Then Aram befriended Sarkis [Zabunyan] (Armenian born in Istanbul in 1938) a conceptual artist in Paris.

Aram went to Turkey to buy carpets and visited his relatives in Istanbul and traveled to Beirut. Aram’s eldest, Pierre, apprenticed in the family’s carpet shop, and for a year, in 1960, three generations of Iynedjians worked in 7 rue de Bourg, Lausanne before Bedros died next year.

After Aram Iynedjian’s death in 1973, his son Pierre took over the carpet shop in Lausanne. His wife, Georgette, continued her sports and her interest in contemporary art. She died in 2010.

The Fifth Generation

Descendants of Nevart (née Allahverdian) Garabed Baltayan

Ara Garabed Baltayan (born in Istanbul, September 6, 1920—died in New Haven, CT, August 7, 2015) was a smart boy, and his parents doted on him. His childhood home was in Bostandji/Bostancı, a neighborhood fronting the Sea of Marmara in Kadikeuy. The family traveled to visit his relatives in Constanța, and in the summer they enjoyed Heybeli Island [18], and Emirgan on Bosporus.

Ara attended the eminent Robert College; it was established in 1863 on the Bosporus by Christopher Robert, a American philanthropist, and Cyrus Hamlin, a missionary. Ara received dual degrees in Mechanical and Electrical Engineering. As Turkey made military service compulsory, Ara fulfilled his duties as an officer given his education. Later, he worked for an American reserve officer in Izmir/Smyrna. Ara married an Armenian secretary, who worked at the college and had a son born in circa 1945.

In 1951, the Ashekian family—Garabed, Berjouhi and the twins, Aida and Baruir— were on a ship from Constanța to arrive in Beirut. When their ship stopped at Izmir, they spent time with Ara Baltayan and his son on May 25th. After that date, Ara left Istanbul because his marriage was not harmonious and fled to the United States, leaving his wife and son in Turkey.

Ara continued his education attaining a Master’s in Engineering at Yale University. He excelled in Research and Development for many years. Employed as a professional engineer, he worked improving traffic lights.

Ara Baltayan married Mary (néeMelkdon Arakelian) Baltayan (born in Waterbury (CT) on January 6, 1918—died in New Haven, CT, on June 20, 2010); her mother’s maiden name was Mary Nazarian and had two sisters, Elizabeth Arakelian and Ann Balayan and a brother, Jack Arakelian. Mary was a second generation, Armenian American who spoke Turkish. Her father owned a rug shop in New Haven where the family lived. Mary worked for the railroad after high school and was very active on the boards of the YWCA (Young Women's Christian Association) and ASA (Armenian Student Association). [19]

Ara and Mary had two sons, and a daughter:

- Charles Ara Baltayan (born in CT, in 1953) is a jeweler, married Mary (née Grillo) Baltayan (born in CT 1957). They have two sons: Charles (born in CT, in 1987) and Aram (born in CT, in 1996)

- Arthur Ara Baltayan (born in CT circa 1950) is in real estate broker and remodeler, married Linda (née Barbutto) Baltayan in 2000.

- Rosemary/Ro (née Baltayan) Ronald Morris (born in CT, in 1950s) and had Raymond Morris and Melissa Morris; live in Dahlonega (GA)

Ara Baltayan was involved in the Rotary International for decades where he served as Past President of the New Haven Club. Mary was famous for her baklava and taught at the Sunday school. Ara loved photography and sailing his little sailfish at Owenego in the waters of Long Island Sound.

The Fifth Generation

Descendants of Kevork and Kohar Allahverdi’s two Sons

Taniel Kevork Allahverdi (born in Istanbul in 1925—died in Istanbul in 2007) attended Armenian schools, including Getronagan School, prestigious in Constantinople since 1886. It is located in Karaköy district, attached to the Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church. He completed his military service and was commissioned as an officer in 1949.

Returning to Istanbul, Taniel worked for his father briefly. Then he established his private business, a hardware shop in Nishantashi/Nişantaşı, a popular shopping and residential district, one of Istanbul's most exclusive neighborhoods.

Taniel married Sophia (born in Istanbul in 1927—died in Istanbul in 1994) circa 1950; she was Greek and learned Armenian. The couple had two daughters:

- Ani (née Allahverdi) Tuncer (born in Istanbul in 1952) her grandmother Kohar Allahverdi raised her in her home. She has two daughters, Celine and Lerna.

- Sona (née Allahverdi) Artinian (born in Istanbul in 1954) has a daughter, Elizabeth, and two grandchildren.

Taniel was on the choir of his Armenian Church in Istanbul and in the summers, he enjoyed fishing on his small boat around Kınalıada--the island where Armenians from Istanbul spent their summers.

Sahag Kevork Allahverdi (born in Istanbul 1933—died in Istanbul 2017) was a studious lad. After completing his military service, he became a reserve officer. In 1952, he traveled to Lebanon to see his sister, Sona and his brother-in-law, Pakrat, and his family, and his baby niece. Sahag worked for his father for a while, then other people.

In his youth, Sahag played the accordion. When he was 18 years old, he broke his arm; an Armenian nurse took care of him. He fell in love with her; although much older than him, he was faithful to her until her death. She was the sister of Alice Sapritch (1916-1991), a famous actor of film and TV and singer in France. The couple visited Sapritch in Paris.

The Fifth Generation

Descendants of Kevork and Kohar Allahverdi: Sona and her Friends

Adriné Guéomlekdjian (born in Constantinople circa 1910—died in Beirut in early the 1980s) lived with her parents in the Narlı Kapu neighborhood close to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. Her parents died early, left her orphan; then her maternal uncle and his wife placed her at the Kalfayan Orphanage for girls. When she completed her educational studies, she became a lady’s companion to Mrs. Simon Kayserlian. This affluent couple had a villa in Cimiez-Nice, and Adriné enjoyed the summers along the Riviera.

About 1947, Adriné met a man and they were going to be married. At that time, the Soviets encouraged Armenians from the Middle East to repatriate to Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR); her husband-to-be left from Istanbul. She was to follow him; however, Turkey stopped caravans, so she went to Beirut to take the next ship. Before she left Istanbul, the Patriarchate of Constantinople gave Adriné a recommendation letter addressed to Karekin I Catholicos of Cilicia in Antelias (1945-1952). In Lebanon she would do alternations and sewing for the Catholicos and he discouraged her to go to Armenia. Karekin I was born in Karabagh, he lived and served the Armenian Church until 1935 in Tsarist Russian and later in the Soviet Union.

When Adriné departed the Kayserlians, they gave her a sewing machine and little cash. Still she had resources: she spoke Armenian, Turkish, and French, later learning some Arabic. She could sew, knew several types of embroidery such as cutwork, needle lace, gold-work, and drawn thread, and she was a good cook, as well as congenial, having positive social skills. She started working by babysitting and caring for the elderly as well as sewing/embroidery. Eventually she had an apartment on Tanoukhin Street, Hamra; it had three bedrooms, a sitting room, kitchen, two bathrooms and four balconies. It was close to the American University of Beirut, so she lodged college students whose families were outside Lebanon; she cooked for them and did their laundry. [20] She suffered of dementia and was sent to the Armenian CAHL Elderly Home in Bourj Hammoud until her death. Adriné’s childhood was hard; but she was resilience and made her life meaningful and warm.

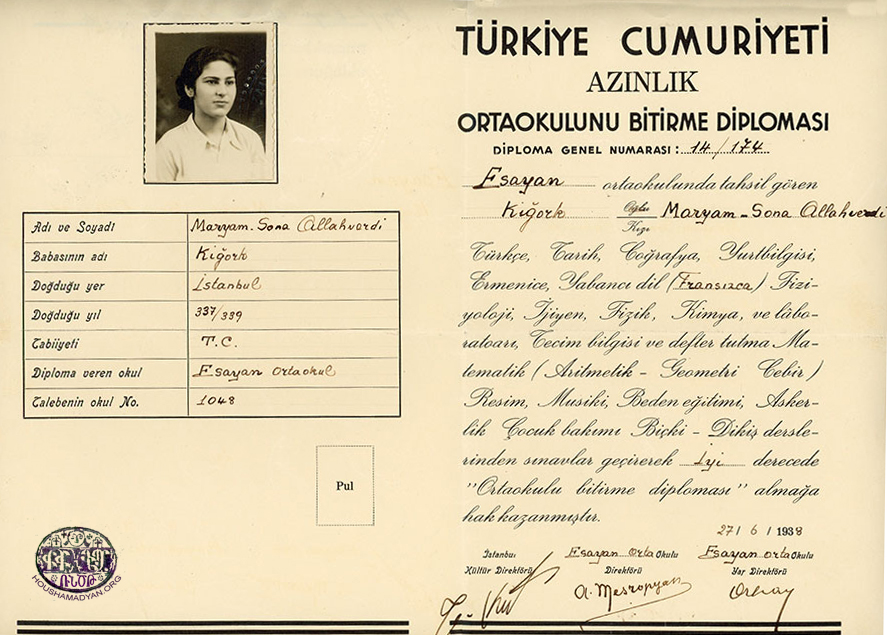

Fransouhie Partikian/Partikoğlu (called Partik) (born in Istanbul in 1921—died in Chicago in 2007) graduated with Sona from Esayan School in 1938. She became a nurse and immigrated to the United States. Once she had her citizenship, she brought her mother and brother Garbis from Istanbul. Partik corresponded with Sona often. In the summer of 1973, Partik came from New York and Araxie came from Istanbul for a reunion chez Sona in Roumieh (Mount Lebanon).

Partik met Berjouhie/Suzy Oksuz from nursing school in Istanbul. Berjouhie grew up in Ankara after the Genocide; she learned Armenian from her friends. After serving several hospitals, these nurses ended at Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital. They lived in the staff residence of the hospital. Most of their big meals were at Silver Star Diner (65th Street and Second Avenue); the owner was a Greek and made them feel at home. They saved their salaries to travel to Europe or the Americas. When the hospital decided that the dormitory would be dismantled, Partik and Berjouhie retired and rented an apartment from a Bolsetsi friend in Queens. When Partik’s health and memory needed help, Nadia her cousin and her husband Arman Krikor/Mirijian moved her and Berjouhie to Chicago. Partik died first then Berjouhie few years later.

Araxie (née Antreasyan) Garbis Ugurlian and Sona graduated from Esayan School in 1938. Araxie continued the Deutsche Schule Istanbul (established in 1868). Her husband had a rug store in Istanbul, but later he took Armenian tourists from Istanbul to Armenia, Aleppo, etc. They had two sons; one is a doctor in Austria. Her sister Anais (née Antreasyan) married in 1963 Zareh Yaldizciyan (born in 1924—died in 2007), a poet. His poems were in Western Armenian language, his pen name was Zahrad.

Alin (née Mamprelyan)Kalenderoğlu (born in Istanbul in 1926—died in in Istanbul in 2010) her father changed their name from Mampelyan to Görener in 1957. She graduated the renowned Notre Dame de Sion. She wanted to go to university, but her father would not allow her. She went to Lebanon in 1956 for few months visiting Sona. Then she taught French and literature with her alma mater. In 1971, Aline worked in the accounting department of Pan America World Airlines in the Istanbul Office. She had the opportunity to travel to China and North and South Americas, and she passed through Beirut. After 20 years in her corporation, she retired and had more time to travel to visit her friend Sona in New York. Aline married Sahag Kalenderoğlu who had completed all his medical school in Istanbul and was a good student; however, because he was Armenian, his professors gave him low grades so he could not practice medicine. He sold oriental carpets! They had a son and a daughter:

- Aleks Kalenderoğlu (born in Istanbul in 1967) studied Mathematics and Astronomy, he became a priest of the Theravada Monastery, Thailand in 2015

- Lin (née Kalenderoğlu) Özyönüm (born in Istanbul in 1968) teaches at Notre Dame de Sion and has a son and a daughter

Hermine (née Bedrossian)Varjabedian (born in Damascus, in 1925—died in Los Angeles, in 2017) her parents were Karnig and Nevart (née Mesjian), from Akshehir/Akşehir, after the Genocide they settled in Damascus; eventually they moved to Beirut in 1925. Her father opened a bakery in Khandaq al-Ghamiq where many Armenians lived. The Bedrossian had three children, Artaki, Hermine and Berj. Hermine attended Hripsimiants School. Then she attended Beirut College for Women (now Lebanese American University) where she received her AA degree in child psychology.

Hermine married Dr. Dikran Varjabedian in 1951. He was a radiologist and author. Dikran and his brothers Sisag [wrote History of the Armenians in Lebanon] and Hratch and their mother, Victoria, were deported from Marash in 1915. They were settled in Aleppo in 1922. In 1923, Dikran and his brothers were placed at the Bird's Nest orphanage in Jbeil/Byblos. Victoria supported her family by working as an outpatient nurse at the American University of Beirut Hospital. Dikran graduated in 1929 from the Armenian Evangelical Central High School and then attended the American University of Beirut and graduated in Medicine in 1937. In 1947 he went to Harvard Medical School and specialized in radiology.

Hermine wrote a book, The Great Four: Mesrob Mashdots, Komidas Vartabed, General Antranik, and Toros Toramanian, was published in 1969. She was active in the AGBU and the Chairwoman of the Women’s Association. Hermine’s husband died in 1977 during the Civil War of Lebanon, so she immigrated to the United States.

In California, Hermine became a guidance counselor in the Pasadena public school district to help Armenian students. She had three children:

- Loussayk is a speech-language pathologist in Montreal

- Irena is a lab technician in a hospital in Glendale

- Hrag is an Anthropologist, wrote: “The Poetics of History and Memory: The Multiple Instrumentalities of Armenian Genocide Narratives”

Zabel (née Momdjian) Pilavdjian (born in Damascus in 1923) the daughter of Hagop and Siranoush Momdjian from Dikranagred/Diyarbekir, she had two elder brothers, Thomas and Simon. She was educated and her French was fluent, and after her high school she had worked in Damascus with Air France.

In July 1948, she was married a dentist, Khachadour Pilavdjian (born in Aksheir in 1911—died in Beirut, on May 11, 1966). After the Genocide his parents moved to Damascus. He had two sisters; Noyemzar and Shahnar both got married and lived in Marseille. Khachadour graduated from Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth in dentistry. He opened his dental clinic in his residence on Place Debbas. Dr. Pilavdjian was on the men’s committee in Veradznount association. They had a daughter:

- Veronique (Vera) (born in Beirut in 1949—died in Paris circa 1984) the doctor’s mother was called Vera (née Bedrossian) Pilavdjian.

Zabel’s husband died of cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 55. The salary of a widow was limited; she took boarders in her home; they were Armenians from Cairo waiting for their U.S.A. visas.

Veronique attended Collège Protestant Français in Beirut and was studious and loved history. At 18 years old, she was excited to be admitted at Lycée Fénelon because it prepared women to the École Normale Supérieure. After the first academic year, she returned to Beirut. She had lost half of her weight; later this malady was called Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. Her mother joined her in Paris and took care of her. She died in her mid-30ths. Zabel was successful in her job and social life in France, but forever mourned her daughter.

Julia (née Bazirganian) Sarkis Bezdikian (was born in Constantinople circa 1913—died in Italy circa 2000) was the daughter of a doctor in Constantinople; she had an elder sister, Ebrue, and two brothers, both doctors. She grew up with nannies that taught her French and English. Her parents sent her to the American Junior College for Women in Beirut circa 1931. The campus was in Kouraytem/Hamra, Julia’s dorm mate was Salma Nassar (1913-1967). Nassar became the first woman to have Ph.D. in Nuclear Physics in Lebanon, while Julia read novels and had fun. They remained friends until Salma’s death of Leukemia. In her forties, Julia married Sarkis Bezdikian. He was born in Marash,he was the mayor/moukhtar of Bourj Hammoud Armenian neighborhood (north of Beirut). Although Julia and Sarkis came from different backgrounds and upbringing, they loved each other.

Julia became Sona’s friend, and gave her English classes. First the couple lived in Bourj Hammoud on Armenia Street; Sarkis’s brother’s family lived in that compound; and had a bakery on the street floor. His nephew, Assadour Bezdikian, was about 14 years old, a gifted artist, but not interested in school. Sona introduced Assadour to the artist Jean Guvderelian (Beirut 1923-2016) who later opened the Guvder Institute; Assadour was one of his successful students. Before Assadour left for Paris, he gave Sona a thank you painting he made in 1958.

In the 1960s, Sarkis and Julia built a house in Deir el Kalaa, Beit Mery, their land was on the ancient Roman town and they found ruins when digging. Sarkis cooked most of their meals; his red lentil Marash soup was delicious. The couple was hospitable and entertained Julia’s friends with antics—she would dress up as Tarzan and Jane or Femme Fatale.

Anahid (née not known) Umourtajian (born in Istanbul circa 1923—died in Beirut during the Civil War), her sweetheart Onik Umourtajian had left the Republic of Turkey to Argentina. When the couple was going to marry, they decided they relocate to Beirut.

The couple lived in a building across the Djemaran of Hamazkayin, an Armenian school founded in Beirut in 1930. The couple did not have children, they were very close to their Armenian neighbors and friends. Onik owned an air-conditioning company, when he died Anahid taught children piano during the Civil War in Beirut.

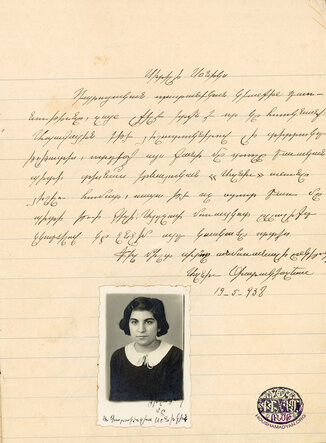

Sona (née Kevork Allahverdi) Pakrat Bakalian (born in Istanbul, May 25, 1922—died in New York, March 27, 2006) was Allahverdian when born, but in 1934, the Republic of Turkey decreed the Surname Law, so all Armenians removed the “ian” and Turkicized their names; her family became Allahverdi.

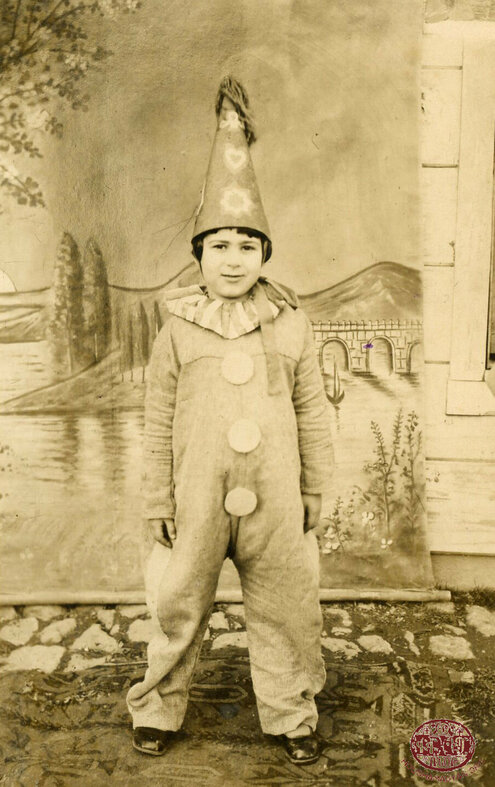

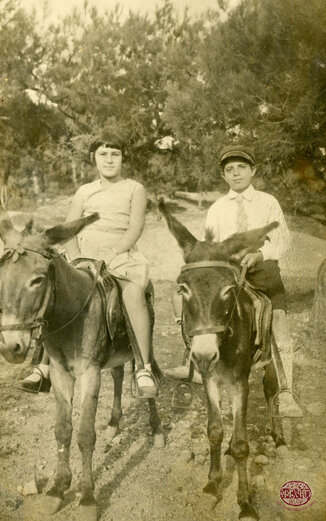

Sona’s childhood was happy and her small family of grandmothers, aunts and uncles, cherished her. She had an Armenian education: first at Aramyan Uncuyan Varjaran [Aramyan Primary School] in Moda, on the Asian part of Istanbul. Then when her family moved to Kurtulush on the European part of Istanbul, she continued her studies at the Essayan School in Taksim-Beyoglu,and she received her certificate in 1938.

Next Sona took classes for tailoring-dress making and French language courses and learned piano, embroidery, knitting, crochet, cooking and other skills young women trained for being a homemaker and mother.

In the fall of 1949, Sona’s family received a letter from their relatives inviting them to go to Beirut because her grandmother, Nevrig (née Iynedjian) Allahverdi, had not seen her sister, Diruhi (née Iynedjian) Ashekian, for a long time. [21] Sona, her father Kevork, her mother Kohar and grandmother Nevrig took a plane from Istanbul to Beirut in 1949.

This trip was also the opportunity to introduce Sona to Diruhi’s grandson, Pakrat Sarkis Bakalian. His mother, Haiguhi Bakalian (widowed in 1937) was eager for him to re-marry. All went well, and before the visitors returned to Istanbul, there was a wedding in the Bakalian’s apartment in Khandaq el-Ghamiq because several elderly ladies had difficulty going up and down three flights. Sona joined a large family, many friends and acquaintances and a new country where Arabic is spoken.

Her mother-in-law, Haiguhi, grandmother-in-law, Diruhi, and the newlywed couple lived in the apartment. Further, Haiguhi’s younger sister, Marina Ashekian, who lived with her husband, Bedros, and two daughters, Chaké and Sirarpie, just a few minutes from the Bakalians, visited her mother and sister daily and shopped for their groceries. Being peers in age and very kind, Chaké and Sirarpie helped Sona with her integration into the Armenian community of Beirut; their friends became her friends.

Sona had four children all born in January; the last pregnancy was a set of twins. Houri died as a newborn:

- AnnyBakalian (born in Beirut in 1951) received PhD in Sociology at Columbia University, wrote two books and many articles and built the Middle East and Middle Eastern American Center at the Graduate Center, City University of New York.

- SarkisBakalian (born in Beirut on January 10, 1952—died in Beirut on November 6, 2009) administrator of SIDUL in Beirut.

- Ruby(née Bakalian) Hirant Gulian (born in Beirut in 1953) received a Master’s in Archeology from the American University of Beirut and a certificate in cooking from the New York Restaurant School.

Sona’s mother-in-law and her mother, Haiguhi and Diruhi, helped with the children and continued cooking and managing the household. In 1957, Pakrat and Sona moved their home to a modern building in Badaro with an elevator, in a new neighborhood at the limits of the city and close to the airport. There was crisis in Lebanon in 1958; so Haiguhi and Diruhi moved with them to Badaro. At this time, Sona managed her children, the cooking and the apartment, her husband’s business events and their social lives.

Since the 1950s, Sona was involved with the Veradznount association. It was a non-profit that sponsored sports, had an ensemble that featured Armenian music, as well as offered cultural soirées, such as when Silva Kaputikian (1919-2006) “the grand lady of twentieth century Armenian poetry” visited Beirut in 1963. The women’s committee also offered cooking classes, English classes, and Santa Claus appeared with gifts for needy children at Christmas.

Sona was social and had kept most of her friends wherever she went throughout her life. First Sona befriended girls in school or locals in Istanbul. As soon as Sona married, Chaké (née Ashekian) Najarian introduced her friends to Sona and who became hers. Involved in Veradznount, she befriended the other committee members. Sona also befriended Bolsahai—women from Istanbul living in Beirut with their husbands/families.

In the 1960s, Sona started to help Dzeranozt [Armenian Elderly Home], in Bourj Hammoud (also known as CAHL): Centers for Armenian Handicapped in Lebanon and served as president in the 1970s. She also used her sewing skills at the SOS Children’s Village in Bharsaf (near Bikfaya), helping the local seamstress with weekly visits. Sona also supported the Surp Etchmiadzin Ladies Committee. In 1981, she joined the Committee’s trip to Armenia SSR and met Catholicos Vasken I (1955-1994). Karekin II, Catholicos of All Armenians of Etchmiadzin, in Republic Armenia, awarded Sona in 2005 with the “Surp Nerses Shnorhahli” medal and encyclical for her dedication, devotion, contribution and service.

The Civil War in Lebanon started in 1975, Sona’s husband died of a heart attack in April 1976. Once her daughters moved to New York in 1981, she joined them. While Sona’s friend, Julia (née Bazirganian) Bezdikian, had taught her some English, she assimilated without complaints. She made new friends while she kept in touch with her long-time friends; she traveled back to meet them while in Beirut to see her son, Sarkis Bakalian, and his family, her nieces and friends in Istanbul, and visit Zabel (née Momdjian) Pilavdjian in Paris. She joined Makrine (née not known) Chekerdjian and Eugenie (née Abadjian) Sandrik in the Montecatini Terme (north of Florence) for its healing waters to drink and natural hot spring for the body. She became a proud American citizen and voted during elections. Sona enjoyed Manhattan and its parks, museums, and shows—she was with her Bolsetsi friend, Selma Margosian, at a matinee concert at Lincoln Center when she had a stroke and died within few days.

The Fifth Generation

Descendants of Aram Bedros Iynedjian

Pierre Iynedjian (born in Lausanne in 1940) is the son of Aram Iynedjian; he followed in his father and grandfather’s footsteps in in oriental carpets business. When Aram died, Pierre closed the Berne store, so he had more control of the business in oriental rugs at 7 rue de Bourg, Lausanne.

Pierre married Elizabeth; they went to Beirut for their honeymoon. They have a daughter and a son:

- Vehanouche Iynedjian (born in Lausanne, in 1973), a judge in the canton of Vaud; has twins Baptiste and Pierre (born in 2010)

- Adrien Iynedjian (born in Lausanne, in March 22, 1977), a banker and follows contemporary art; has a son Sevan (born in 2007)

At the turn of the 1990s, the prices of carpets were falling; Europeans were not interested in oriental rugs, which were no longer à la mode. Hence in 1995, Pierre Iynedjian turned his shop into a gallery. His specialization was on geometric, constructivist and minimalist art that he had started to develop from the early 1970s and he knew many of artists. His exhibitions included the work of Joseph Albers, Jean Arp, Max Bill, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Leon Polk Smith, and Victor Vasarely.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Pierre with his second wife, Cannelle, trekked in Northern India, Nepal, Mustang and Tibet. During the vacation they fell in love with the cultures of these people and appreciated their carpets, textiles, painted cupboards, and native objects. In China, he admired their contemporary art; and bought samples.

When Pierre Iynedjian was about 20 years old, three generations of Iynedjians worked in the carpet shop on rue de Bourg. One of those days, Bedros told Pierre, “The Genocide was terrible, but now that we are in Switzerland we live like the Swiss.” Bedros Iynedjian enjoyed his Armenian friends; however, he did not want to be involved in Armenian organizations and churches. Pierre followed his grandfather’s belief. When an earthquake magnitude of 6.8 hit Armenia SSR on December 7, 1988; about 25,000 to 50,000 persons died and over 130,000 were injured. Pierre sent a check to the Armenian Apostolic Surp/Saint Hagop south of Geneva, however, kept his donation anonymous. He also opened his carpet shop to drop material donations, mostly clothing. And many Swiss contributed.

Around 2010, Pierre Iynedjian retired in Verbier (Valais Canton); yet, he was like his ancestors a businessman! He opened a small shop and his office in this ski resort in the Alps; not surprising, he displayed Asian objects and few rugs. He has an apartment in a chalet embellished with contemporary art; and travels from Geneva to Ko Samui, an island in Thailand few times annually. He is proud of his daughter and son and dotes on his grandchildren.

Patrick Bernard Iynedjian (born Lausanne in 1943) is the son of Aram Iynedjian; he received his Bachelor, Gymnase Classique Cantonal in 1962. Then he attended at University Lausanne School Medicine; and in 1968 he achieved his Doctor of Medicine.

Patrick married Dietlinde C. Mayer in 1971 and live in Lausanne on avenue de Rumine. They have two sons:

- Nicolas Pierre Iynedjian (born c. 1974), is an expert lawyer in real estate law in Switzerland with three children: Alice (born in 2001), Joachim (born (born in 2004), and Ulysee (born in 2018) all in Lausanne

- Marc Alexander Iynedjian (born c. 1977) is a lawyer based in Geneva, specialized in corporate mergers & acquisitions; He has two sons: Paul (born 2005) and Alexan (born in 2008)

Patrick Iynedjian’s career was in biomedical research mostly in Switzerland; however, he spent 1973-1975 at Temple University School Medicine in Philadelphia. His first son, Nicolas, was born in the United States. He achieved the cloning of the mammalian glucokinase gene. Since 1984 until his retirement, Dr. P. Iynedjian was affiliated with the University of Geneva School of Medicine.

Aram and Georgette’s love of contemporary art has passed to their children, including Patrick and Dietlinde and their sons. The walls of their apartment are decorated with artworks done by famous artists.

Anne Marie (née Aram Iynedjian) Buhlman (born in Lausanne in November 1945—died in Lausanne in May 2019) married Jean Claude Buhlman (1937-2015) in St. Tropez in 1971. Even though her brother Christian had died three days earlier from an accident, the wedding took place. This couple did not have children; eventually they divorced.

- [1] Garabed P. Ashekian, The History of Uzun Ashekian Clan, Beirut: Donikian Press, 1968. Translated by Vatche Ghazarian (Monterey, CA, 2013).

- [2] Two Jews, brothers-in-law, Adolfe Orosdi and Maurice Back who established a modern and elegant department store they called Orosdi-Back; they started in the Galata district in Constantinople about 1850s. Their enterprise expanded to Adana, Smyrna, Samsun, Cairo, Alexandria, Beirut, Tabriz, Tehran and many cities in the Mediterranean and further.

- [3] At the turn of the 20th century, Harutiun Suzmeyan may have adjudicated disputes within the Armenian community. It’s not clear whether Suzmeyan’s family was part of the Amira class.

- [4] The Khabur River is the tributary to the Euphrates, close to Deir Zor (now in Syria).

- [5] Turkish written in Armenian script.

- [6] In his memoirs Pierre Iynedjian mentions that his grandmother, Pérouze, had eight siblings (Pierre Iynedjian with Barry Edgar, From Art to Art, Hors Ligne Publishing, 1995).

- [7] The Clinique is now a hotel (Iynedjian, From Art to Art, page 29).

- [8] See Ashekian, The History of Uzun Ashekian Clan.

- [9] “In the 1920s, Pastor Kraft Bonnard created an orphanage in Begnins where more than 200 orphans and genocide survivors found refuge.

- [10] Iynedjian, From Art to Art, page 35.

- [11] Ibid, page 35.

- [12] Ibid, page 28.

- [13] Swiss Maturité allows students to apply to university directly; it similar to the International Baccalaureate and the UK A-Levels.

- [14] Dobruja is situated between the Lower Danube River and the Black Sea—the Romanian coast and north-most part of Bulgaria coast.

- [15] Matild Calamanian must have been the daughter of Garabed Calamanian. This address: “Haraket Ordusu cadd. Wo 5, Yesilkoy,” was in Sona (née Allahverdi) Bakalian’s address book. And his sister married Mr. Keldjian; their children were: Elmon, Kohar, Arousiag and Sarkis.

- [16] Formerly this neighborhood was called Tatavla populated by Greeks with their churches, schools, shops and traverses. In 1929, a huge fire razed over 200 houses and consequently called Kurtuluş (Turkish of salvation).

- [17] After their wedding, Kevork and Kohar may have lived in another part of Constantinople, but there are photos that they were in Kurtuluş apartment in the 1930s.

- [18] The Princess Islands (Istanbul) are Büyükada (Big Island), Heybeliada, Burgazada, and Kınalıada.

- [19] On Armenian Student Association (ASA), see Anny Bakalian, Armenians-Americans: From Being to Feeling Armenian, (1993)/2011, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, NJ, p. 247.

- [20] Gagik Stepan-Sarkissian (Armenian Institute in London) contributed to the story of Adriné Guéomlekdjian and we thank him for sharing.

- [21] Haiguhi (née Ashekian) Bakalian was unhappy her son, Pakrat had not remarried after his divorce was concluded in 1946. She told a matchmaker who was going to Istanbul to find a nice girl for her son. The lady came back to Beirut and told Haiguhi that her relatives have a daughter eligible for her son.